QUITNESSET ASSOCIATES, INC. v. DMD PROPERTIES, LLC

QUITNESSET ASSOCIATES, INC. v. DMD PROPERTIES, LLC

MISC 09-414407

May 16, 2011

BARNSTABLE, ss.

Trombly, J.

QUITNESSET ASSOCIATES, INC. v. DMD PROPERTIES, LLC

QUITNESSET ASSOCIATES, INC. v. DMD PROPERTIES, LLC

Trombly, J.

Introduction

This case involves the scope of activities permitted in certain right-of-way easements on registered land in Chatham, Massachusetts, said easements having been reserved to the predecessors in title of Plaintiff Quitnesset Associates Inc. (Quitnesset), over land now owned by Defendant DMD Properties, LLC (DMD).

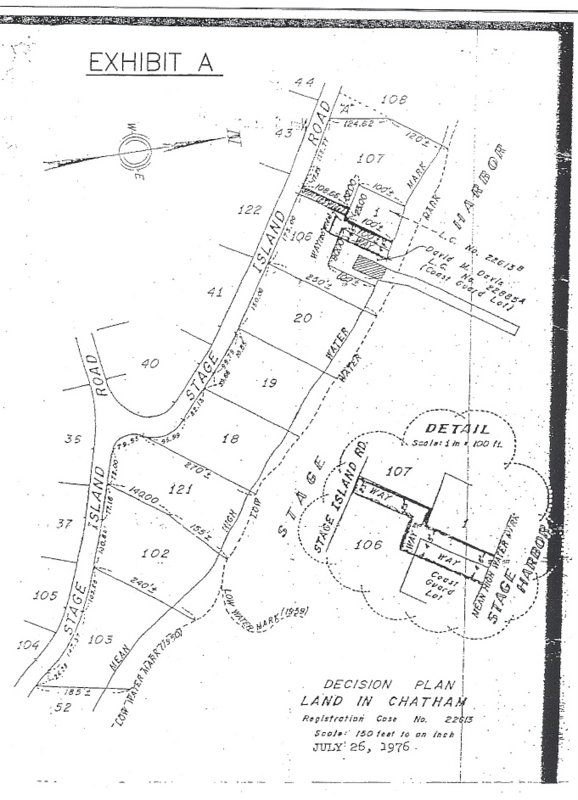

On October 21, 1957, David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis conveyed Lot A shown on Registration Plan No. 25381A and Lot 4 shown on Registration Plan No. 22613A to Edward R. Noyes, together with covenants to convey certain easements. Noyes, holding Certificate of Title No. 21162, later petitioned the Land Court to determine an adequate right of way to fulfill the covenants in said conveyance. By Decision issued on July 26, 1976, the Court (Randall, C.J.) located the easements, described them, and depicted them on a Decision Sketch (the 1976 Decision). Defendant DMD also acquired land which was previously owned by the Davises, including Lot 106 as shown on Registration Plan 22613-K (sheet 2) (Lot 106), and the Coast Guard Lot shown on Registration Plan 22885-A (the Coast Guard Lot).

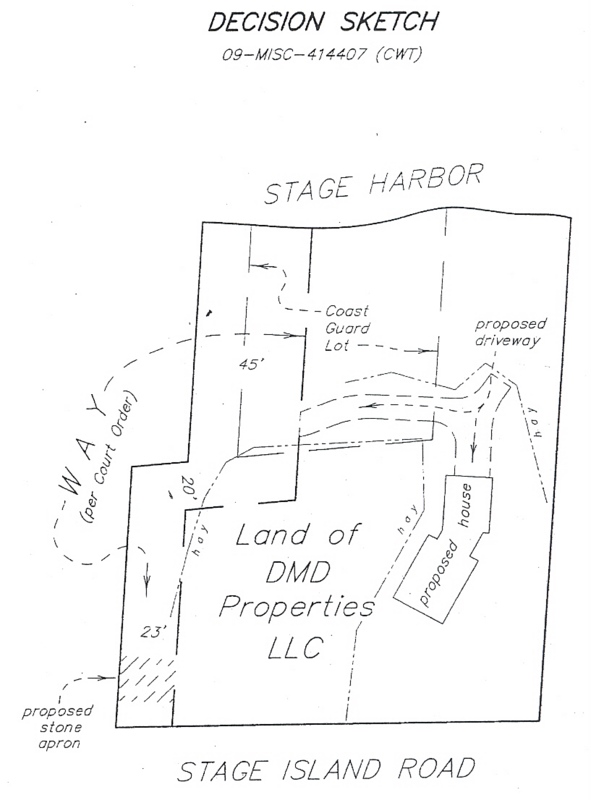

Although the use in all the easements is relevant here, this case particularly concerns the easement 45 feet in width made up of a 20 foot strip of Lot 106 and a 25 foot strip of the Coast Guard Lot, and located in the vicinity of the water at Stage Harbor (the Easement). Quitnesset seeks a declaration that it and its members may tie dinghies within the [E]asement area... [and] maintain a telephone pole or similar object to which to tie dinghies. In August 2009, DMD communicated with Quitnesset stating that boats or dinghies cannot be stored in the Easement and, in September 2009, DMD removed the telephone pole which had been used to tie up and secure the dinghies. DMD also maintains that it may install a combination lock gate across the Easement to prevent unauthorized persons from using the Easement, as long is it provides the combination to the Plaintiff. Quitnesset seeks a declaration that DMD may not interfere with such access by erecting a gate. Finally, Quitnesset seeks a declaration that DMD may not pave a driveway in the Easement (which DMD has obtained zoning approval to do), because that would unlawfully interfere with said Easement. A Decision Sketch showing the easement at issue and the surrounding area is attached hereto.

The parties submitted the matter to court on a case-stated basis. They have stipulated to the relevant facts and submitted agreed exhibits. A hearing was conducted on April 22, 2001, at which counsel argued the case. The matter was then taken under advisement.

Undisputed Facts

I find that the following facts are undisputed:

1. David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis owned the relevant land, two-so called islands Morris Island and Stage Island in Chatham, Massachusetts.

2. By deed dated October 21, 1957, David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis conveyed to Edward R. Noyes Lot A shown on Registration Plan No. 25381A and Lot 4 shown on Registration Plan No. 22613A, together with covenants to convey three easements. Said deed is registered at the Barnstable Registry District of the Land Court as Document Number 563465 (the 1957 Deed). Lot A is not involved in this dispute.

3. The 1957 Deed transferring property from David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis to Edward R. Noyes created an easement over the remaining land of Davis. The language in the deed recites, in relevant part that the Davises are obligated

[a]lso to convey an easement 50 feet wide and at least 150 feet long on said remaining land of the grantors adjoining said last mentioned way when located to be used for boat landings and docking and for parking vehicles on either side of said Dike-Easement or abutting thereon said easement to be located by the grantors on request of the grantee.

4. In 1974, Edward R. Noyes filed a Petition to Determine Right of Way in the Land Court against David M. Davis, Anne Hall Davis, and their successors in title, in the action entitled Edward R. Noyes v. David M. Davis, et al, Case No. 22613-S.

5. By Decision issued on July 26, 1976, the Court (Randall, C.J.) located the easements, depicted the easements on a Decision Sketch, and described them, in relevant part, as the right of way to launch and land boats and to park automobiles in connection therewith over a 23 feet in width running from Stage Island Road along the northwesterly line of Lot 106...; thence to a right of way 20 feet in width along the southwesterly line of Lot 1 through a part of Lot 106 ; thence to a right of way 45 feet in width made up of a 20 foot strip of Lot 106 and a 25 foot strip of the Coast Guard Lot. (the 1976 Decision). [Note 1]

6. Quitnesset and its members are all owners of the property which was previously conveyed to Edward R. Noyes, and which had been conveyed to Noyes by David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis.

7. DMD, also successor in title to David M. Davis and Anne Hall Davis, acquired title to Lot 106 on Land Court Plan 22613-K (sheet 2) in 2003. Said deed is registered at the Barnstable Registry District of the Land Court as Document Number 948889 on Certificate of Title No. 171232. Lot 106 is included within the land of DMD at issue in this case.

8. DMD acquired fractional interests in the Coast Guard Lot, shown as the unnumbered lot on Land Court Plan 22885-A (the Coast Guard Lot) in 2003. Said deeds were registered in the Barnstable Registry District of the Land Court as Documents Numbers 948890 and 948891.

9. DMD subsequently acquired the remaining fractional interests in the Coast Guard Lot. Said deeds were registered in the Barnstable Registry District of the Land Court as Documents Numbers 960509, 970947, 970384, and 988476 on Certificate of Title No. 184861. DMD is now the sole owner of the Coast Guard Lot.

Analysis

Dinghies and Mooring of Boats in the Easement

Quitnesset asserts three reasons as to why it and its members should be allowed to tie dinghies within the [E]asement area... [and] maintain a telephone pole or similar object to which to tie dinghies.

First, Quitnesset points to the language in the 1957 Deed covenanting to convey easements, which states, in relevant part, that it will convey an easement to be used for boat landings and docking. (emphasis added.) The Plaintiff also asserts that the 1976 Decision was insufficient in determining the scope of said easement, or was ambiguous on the matter. However, the Plaintiffs assertions are contradicted by the details of the case leading to the 1976 Decision, and by the detail in said Decision. In that case, the Court heard three days of trial, including witness testimony, and also examined the relevant deeds and purchase and sale agreements, to come to its detailed conclusion as to the location as well as the scope of said easements. Specifically, in the 1976 Decision, the Court depicted the easements on a Decision Sketch, and described them, in relevant part, as

the right of way to launch and land boats and to park automobiles in connection therewith over a 23 feet in width running from Stage Island Road along the northwesterly line of Lot 106...; thence to a right of way 20 feet in width along the southwesterly line of Lot 1 through a part of Lot 106 ; thence to a right of way 45 feet in width made up of a 20 foot strip of Lot 106 and a 25 foot strip of the Coast Guard Lot.

Notably, after considering all of that evidence, the Court did not include anything about docking boats or the use of dinghies. Moreover, the 1976 Decision was not appealed. Indeed, the subsequent conveyances in the chain of title to the Plaintiffs land incorporated the language in the 1976 Decision, and referred to that Decision.

Res judicata is the generic term for various doctrines by which a judgment in one action has a binding effect in another. Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 n. 2 (1988). It comprises both claim preclusion and issue preclusion. Id. It makes a valid, final judgment conclusive on the parties and their privies, and bars further litigation of all matters that were or should have been litigated in the action. Id. at 23. Here, in a prior case between the predecessors in interest to the parties, where there was incentive to litigate the scope of the easements, the Court determined the scope of the easements, including an interpretation of the language in the 1957 Deed. [Note 2] Accordingly, the Plaintiff is barred from re-litigating the scope of the easements by res judicata.

Second, Quitnesset asserts that, by launching and landing of boats, it is implicit that one can also dock them, because [w]hen an easement is created, every right necessary for its enjoyment is included by implication. See Sullivan v. Donahue, 287 Mass. 265 , 267 (1934). However, the specific cases to which the Plaintiff cites are either not relevant to this issue, or involve a specific grant to construct a pier or some similar structure, or where, for example, a deeded access to the water is impossible without constructing a walkway over the mud. There is no evidence that the Plaintiff and its members are unable to exercise their rights in the Easement without the use of dinghies on which to moor boats. Simply put, the Plaintiff and its members are entitled to park and carry boats along the Easement, use the boats, and take the boats away once finished in the water. Beyond the parking of automobiles allowed in the Easement, if Quitnesset or its members leave boats or other items therein, it constitutes an interference with that Easement, and it is also placing such items impermissibly on land owned by DMD. See e.g., See Perry v. Planning Bd. of Nantucket, 15 Mass. App. Ct. 144 , 158 (1983), quoting Western Mass. Elec. Co. v. Sambo's of Mass., Inc., 8 Mass. App. Ct. 815 , 818 (1979) (one with rights to use an easement may use the land for all purposes which are not inconsistent with the easement . . . or which do not materially interfere with its use.) (emphasis added). Leaving items in the Easement, such as boats and dinghies, would interfere with the rights of others in that Easement. Thus, the Plaintiffs second argument fails as well.

Third, the Plaintiff argues that it is entitled to place dinghies in the water to moor boats in the Easement by virtue of the language in a letter, dated December 10, 1976, from Richard J. Cain, Esq. (who was counsel to Noyes in the 1974 Petition) to Edward Noyes, and because of Quitnessets and its predecessors in interests long-time use of dinghies since the 1970s. The letter, following the 1976 Decision, states, in relevant part, that

All owner of lots, then, at Morris Island have a right to use this right-of-way, to get to and from Stage Harbor, this being intended to take care of the easement to be used for boat landing and docking and parking vehicles called for in the original deed from Davis to Noyes, and the right to which easement Noyes in turn passed along to all subsequent lot owners on Morris Island.

(Emphasis added.) Plainly, the language in the letter does not create any docking rights, but merely confirms which easement in the 1976 Deed this resolved. [Note 3] The fact that DMDs predecessors in interest may have allowed the dinghies to remain, at most, constitutes a revocable license. See e.g., Mason v. Albert, 243 Mass. 433 , 437 (1923). Further, because this is registered land, there can be no acquisition of prescriptive rights by the Plaintiff. G.L. c. 185, §53 ( [n]o title to registered land, or easement or other right therein, in derogation of the title of the registered owner, shall be acquired by prescription or adverse possession.). Accordingly, this third argument by the Plaintiff fails.

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the above, there remains a further issue as to the location of the dinghies and the telephone pole, in relation to the water line. [T]he ancient and unique feature of Massachusetts land law which provides that every owner of land bounded on tidal waters, such as the landowners here, enjoys title to the shore and to the adjacent tidal flats all the way to the low water mark (or one hundred rods, whichever is less). Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998). Beyond the low water mark, ownership of land is ordinarily vested in the Commonwealth, with activities such as moorings regulated by the areas harbormaster. See, e.g., G.L. c. 91, §10A. To the extent that any boats, dinghies or telephone poles are above the low water mark, said items are not permitted to remain in the Easement. However, because the record does not contain sufficient evidence regarding the precise location of the dinghies, which may be below the low water mark, further evidence or a trial would be required to resolve that matter. This does not preclude the Court from ruling on the extent of the easement above the low water mark.

The Proposed Combination Lock Gate

DMD asserts that it is necessary to install a combination lock gate to prevent those without rights from using the Easement. DMD would provide the combination to those who have Easement rights. Quitnesset contends that installation of a gate would be extremely burdensome to its use of the Easement, because, to proceed, it would require stopping an automobile to open the gate, driving through, closing the gate, and driving to proceed; the process would have to be done going in both directions both going to and coming back from the area near the water.

The applicable standard for this matter is that the servient owner retains the use of his land for all purposes except such as are inconsistent with the right granted to the dominant owner or acquired by him, and, if gates or bars are appropriate to facilitate that use, he may establish or maintain them if no material interference with the easement results. Merry v. Priest, 276 Mass. 592 , 600 (1931) (emphasis added).

DMD has presented only minimal evidence of unauthorized use of the Easement by commercial fisherman, and most of those instances occurred before the area was developed to its current state. On the basis of what the Defendant introduced, and because Quitnesset and its members may only park and bring boats over the Easement to launch, land it, and bring them back home, I conclude that to erect a gate within the easement area would materially interfere with the Plaintiffs use of the Easement.

DMDs Proposed New Driveway

The Defendant has obtained an Approval, dated March 2, 2009, from the Town of Chatham Zoning Board of Appeals, to construct and maintain a driveway on Lot 106. DMD asserts that the driveway (to accommodate a new proposed dwelling) would not materially interfere with the Plaintiffs use of the Easement, because the Easement is non-exclusive and the Plaintiff and its members would always have to park their vehicles to one side, in any event, to allow others to pass. Quitnesset asserts, on the other hand, that it would materially interfere with and/or limit the scope of the easements.

Generally, the paving of a portion of a road in an easement is permissible. See Glenn v. Poole, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 296 (1981) (Clearing limbs from a roadway, smoothing the surface of a way, placing gravel on a road, or even paving a road have been condoned as reasonable repairs, if necessary to enjoyment of the easement). After reviewing agreed Exhibit No. 9 and the Zoning Board Approval, it appears that the proposed driveway would not constitute an interference with the easements. [Note 4] However, it also is evident that certain temporary physical features (such as bales of hay) required for the construction of the proposed dwelling would limit the width of at least one portion of the easements. Such temporary structure(s), which appear to be necessary during construction due to the presence of wetlands, may remain for a reasonable period of time, in order to complete that construction. If DMD causes any permanent structure to be placed in the easements, thereby limiting them, it would be impermissibly interfering with the rights of those entitled to use the easements.

It should be noted, however, that the parties may jointly or separately petition the court to relocate the easements, or portions of them. In the absence of agreement by the parties, DMD may petition the court to relocate an easement, relying upon the Supreme Judicial Courts holding in M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 88 (2004) that the owner of a servient estate may change the location of an easement without the consent of the easement holder. In M.P.M. Builders, the Supreme Judicial Court decided the question of whether the owner of a servient estate may change the location of an easement without the consent of the easement holder. [Note 5] In holding that the servient estate owner may do so upon satisfaction of certain criteria, the Supreme Judicial Court announced its adoption of the rule expressed in Section 4.8(3) of the Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) (2000), which provides as follows:

Unless expressly denied by the terms of an easement, as defined in § 1.2, the owner of the servient estate is entitled to make reasonable changes in the location or dimensions of an easement, at the servient owners expense, to permit normal use or development of the servient estate, but only if the changes do not (a) significantly lessen the utility of the easement, (b) increase the burdens on the owner of the easement in its use and enjoyment, or (c) frustrate the purpose for which the easement was created.

M.P.M. Builders, 442 Mass. at 90. This Court has previously held that the M.P.M. Builders holding is not limited to unregistered land. Randall v. Nadis, 09 SBQ 18211 11 001, Order Granting Partial Summary Judgment to the Plaintiff, dated March 21, 2011 (Cutler, J).

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that:

(1) The Plaintiff is barred from re-litigating the scope of the easements by res judicata;

(2) Quitnesset and its members may not leave boats, dinghies, telephone poles, or other items inconsistent with the easements, in the area of the easements;

(3) DMD may not place a gate across the area of the easements;

(4) DMD may construct the proposed driveway, and may allow minor, temporary, restriction in the width of the easements for a reasonable period of time in order to complete construction associated with the new proposed dwelling; and

(5) A trial, or further evidence, would be required to determine whether the dinghies, telephone poles, and boats lie beyond the low water mark, and to determine what rights, if any, the Plaintiff and its members would have under those circumstances.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

Charles W. Trombly, Jr.

Justice

Dated: 16 May 2011

Exhibit A

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] A copy of the Decision Sketch from Chief Justice Randalls Decision is attached hereto as Exhibit A.

[Note 2] Previously, after the Court endorsed a memorandum of lis pendens, the Defendant filed a Special Motion to Dismiss, under G.L. c. 184, §15, arguing res judicata. Although in 2009, the Court denied the Defendants Special Motion to Dismiss as to that basis, the Court retains the power to reconsider, without rehearing, an issue, or a question of fact or law until the case has passed beyond the power of the court by the issuance of a final judgment or decree. See Peterson v. Hopson, 306 Mass. 597 , 601,602 (1940).

[Note 3] As already explained above, the 1976 Decision description of the relevant easements and their location is definitive, and the Plaintiff is barred from re-litigating the matter based on what is in the 1957 Deed, which was before the court in 1976.

[Note 4] Of course, DMD is allowed to have the automobiles from the new dwelling travel over the easements, provided they do not park in the easement and block others from traveling over it.

[Note 5] The Supreme Judicial Court had previously concluded that a dominant estate owner (easement holder) may not unilaterally relocate an easement. M.P.M. Builders, LLC v. Dwyer, 442 Mass. 87 , 90 [n. 4] (2004), citing Kesseler v. Bowditch, 223 Mass. 265 , 269-270 (1916) and Jennison v. Walker, 77 Mass. 423 (1858).