357 CIRCUIT AVENUE LLC v. MARK ABBOTT and LISABETH OSTAR

357 CIRCUIT AVENUE LLC v. MARK ABBOTT and LISABETH OSTAR

MISC 10-426729

June 28, 2011

BARNSTABLE, ss.

Long, J.

357 CIRCUIT AVENUE LLC v. MARK ABBOTT and LISABETH OSTAR

357 CIRCUIT AVENUE LLC v. MARK ABBOTT and LISABETH OSTAR

Long, J.

Introduction

There are two neighboring properties in Bourne, one owned by plaintiff 357 Circuit Avenue LLC and the other by defendants Mark Abbott and Lisabeth Ostar (the Ostars). Each has its own driveway which serves all its access needs. Plaintiffs driveway connects to Hope Avenue. Defendants driveway connects to Circuit Avenue. Joining the two driveways would thus create a shortcut between Circuit Avenue and Hope Avenue for the two sets of owners. [Note 1] This, though, would come at some inconvenience. Neither could park in their driveway (it would block the others use) and, because the defendants lot is small and narrow, cars from the plaintiffs side would drive almost directly under the defendants windows.

Despite this, defendants and plaintiffs predecessors, Paul and Donna Archibald (the Archibalds), agreed to connect the driveways and signed a mutual easement agreement. No money changed hands. The only consideration was the mutuality of the easement. There was a major condition, however fully understandable in light of the tight conditions at the Ostars narrow lot. The easement would terminate, immediately, once the Archibalds conveyed their property. Conveyance was defined as having only two exceptions: mortgaging and leasing.

The Archibalds have now transferred title to their property to the plaintiff, a limited liability corporation. They allege that the corporation is controlled by their family, but there is nothing either in or required by the corporate filings that would show that. Nor is there anything not even an allegation in plaintiffs pleadings that reveals the identities of all the family members. The Ostars thus assert that the easement has terminated and, accordingly, have blocked the driveway connection.

The plaintiff brought this action seeking a declaration that the easement remains. The Ostars counterclaimed for a contrary declaration and, in addition, asserted a series of counterclaims: (1) negligent interference with property; (2) intentional and malicious interference with property; (3) negligent infliction of emotional distress; (4) intentional infliction of emotional distress; (5) fraud; (6) negligent misrepresentation; (7) intentional misrepresentation; and (8) slander of title. Plaintiff has now moved to dismiss these counterclaims pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(1) & (6), contending that they fall outside this Courts subject matter jurisdiction. For the reasons set forth below that motion is ALLOWED and the counterclaims are each DISMISSED, WITHOUT PREJUDICE. Since the validity of the easement can be decided on the pleaded facts as a matter of law, I reach that question as well. Mass. R. Civ. P. 12(c). The easement was extinguished by the conveyance to the plaintiff corporation. These rulings resolve the case in full, and judgment shall enter accordingly.

Background

Since this is a motion to dismiss and, in the case of the easements validity, a motion for judgment on the pleadings, I take the facts from the parties pleadings and, where documents are involved, from the documents themselves. See Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 529 (2002); Curtis v. Herb Chambers I-95 Inc., 458 Mass. 674 , 676 (2011); Ng Bros. Constr. Inc. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 647-48 (2002).

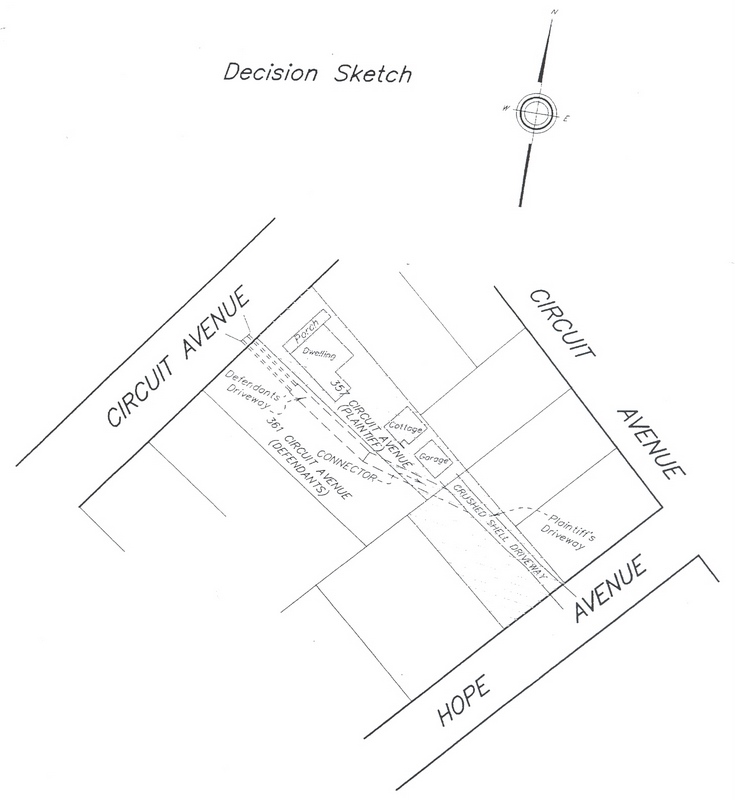

On December 29, 1992, Paul and Donna Archibald owned the property located at 357 Circuit Avenue in Bourne (357). 357 abuts Circuit Avenue on the water side and extends behind to Hope Avenue. Its driveway comes from Hope Avenue and terminates mid-lot at a garage. See the attached Decision Sketch. The Ostars property, 361 Circuit Avenue (361), abuts 357 to the south-west. Id. The Ostars driveway connects to the water-facing portion of Circuit Avenue and runs parallel to 357s property line. Id.

On December 29, 1992, the Archibalds and the Ostars executed and recorded a document entitled Mutual Easement allowing the driveways to be joined and each to use the others for access and egress. No parking was allowed. The easement, however, included a very specific limitation. It would remain in effect only so long as the Archibalds did not convey their property. The parties agreed that neither a lease nor a mortgage would constitute a conveyance within the meaning of this provision. There were no other exceptions.

On February 8, 1995, Paul Archibald transferred his interest in 357 Circuit Avenue to Donna Archibald for nominal consideration. Twelve years later, on March 30, 2007, Donna conveyed the parcel to 357 Circuit Avenue LLC, a limited liability corporation allegedly controlled by the Archibald family, for $1,212,000, and the record suggests that the property became primarily an income-producing rental after that. In response, in February 2010, the Ostars erected a fence along their property line, cutting off access to their driveway. Joseph T. Doyle, Jr., the manager of 357 Circuit Avenue LLC and attorney to the Archibalds, requested that the Ostars remove the fence, arguing that it was in violation of the Mutual Easement agreement. The Ostars refused, contending that the conveyance to 357 Circuit Avenue LLC terminated the easement by its terms. In response, plaintiff brought this suit, arguing that because the Archibalds have control of the corporation, the conveyance to the LLC was not a conveyance within the meaning of the termination language.

Discussion

The driveway easement is governed by the terms in the Mutual Easement executed and recorded on December 29, 1992. By those express terms, either partys right to use the others driveway ceases immediately upon the conveyance by Paul A. Archibald and Donna S. Archibald of the property now known and numbered as 357 Circuit Avenue. Since that agreement, the Archibalds have conveyed 357 Circuit Avenue to 357 Circuit Avenue LLC. The question thus presented is whether that conveyance was a conveyance within the scope and meaning of the Mutual Easement agreement.

The principles governing interpretation of a deed are similar to those governing contract interpretation. Estes v. DeMello, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 638 , 642 (2004). Such interpretation is a question of law for the court where the descriptions [therein] are definite, certain, and free from ambiguity. Massinda v. Lurvey, 12 LCR 95 , 97 (2004) quoting Panikowski v. Giroux, 272 Mass. 580 , 582 (1930) (internal quotations omitted). Where parties disagree as to the interpretation of a writing, courts look to the presumed intent of the grantor [and derive] meaning from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Doherty v. Eligene, 15 LCR 29 , 30 (2007), quoting from Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998); see also Haugh v. Simms, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 781 , 785 (2005). Here, the case turns on the meaning of the word conveyance and there is no cause to look beyond that word since it speaks unambiguously. See Mejia v. American Casualty Company, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 461 , 465 (2002) (holding that when the words of a contract are not ambiguous, the contract will be enforced according to its terms).

A conveyance is defined as a transfer of an interest in real property from one living person to another, by means of an instrument such as a deed. Real Estate Bar Assn for Mass., Inc. v. Natl Real Estate Info. Servs., 609 F. Supp. 2d 135, 140 (D. Mass. 2009) quoting Blacks Law Dictionary 358 (8th ed. 2004), revd on other grounds 608 F.3d 110 (2010). See also Real Estate Bar Assn for Mass., Inc. v. National Real Estate Information Services, 459 Mass. 512 , 519 (2011) (defining conveyancing as the act or business of drafting and preparing legal instruments, esp. those (such as deeds or leases) that transfer an interest in real property) (citing Blacks Law Dictionary 383 (9th ed. 2009). Where a word with such broad meaning (as noted above, it includes the transfer of any interest in real property) is qualified or excepted by subsequent language, the exception of a particular thing from general words proves that the thing excepted would be within the general clause had the exception not been made. Arnold v. United States, 147 U.S. 494, 499 (1893) citing Brown v. Maryland, 12 Wheat. 419, 438 (1827). The fact that the parties specified only two exceptions to the termination clause leasing and mortgaging thus indicates that the breadth of the term conveyance otherwise controls. [Note 2] George W. Wilcox, Inc. v. Shell E. Petroleum Prods., 283 Mass. 383 , 388 (1993), citing Beach & Clarridge Co. v. American Steam Gauge & Valve Manuf. Co., 202 Mass. 177 , 182 (1909).

The March 30, 2007 deed from Ms. Archibald to 357 Circuit Avenue LLC was clearly a conveyance of an interest in real property. It was a deed. It was between legally distinct parties. And it was done for full consideration $1,212,000. It thus terminated the easement. The fact that the conveyance was made to an LLC allegedly controlled for now by the conveying parties does not change the fact that it was a conveyance. By requiring the Archibalds to be the owners of the property, the Ostars made clear that they were contracting only with known, disclosed individuals. The transparency contemplated by the easement language the ability to know, simply and definitively, when the property is no longer held by the benefited individuals is completely defeated when ownership disappears into corporate form. See Patricia Kelley Enter., LTD v. Rockport Realty Trust, 18 LCR 362 , 363 (2010). Once in an LLC, the property is effectively in anonymous, undisclosed ownership and the burdened parcel has no assured way of knowing whether the burden (the driveway easement) continues or not. [Note 3] Id. (holding that easement rights providing driveway access to a property that were limited to the grantors descendents were extinguished by the conveyance of the property to a nominee trust, even though the ultimate trust beneficiaries included some of the descendents). As noted in that case, had a form of disguised ownership been contemplated by the parties to the [Mutual Easement agreement], the reservation could easily have included a policing mechanism. Id. The absence of such a policing mechanism is further confirmation that conveyance to an LLC terminates the Mutual Easement agreement.

I now turn to the Ostars counterclaims. The Land Court is a court of limited jurisdiction. See G.L. c. 185 §§ 1, 3A. The Ostars claims for negligent interference with property, intentional and malicious interference with property, negligent infliction of emotional distress, fraud, negligent misrepresentation, intentional misrepresentation, and slander of title are each tort-based causes of action outside this Courts subject matter jurisdiction. See Norwest Bank v. McKinnon, 12 LCR 75 , 77 (2004); Commonwealth Trust v. Smith, 16 LCR 63 , 66 (2008). They are therefore DISMISSED, WITHOUT PREJUDICE.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that the mutual easement at issue in this case has been terminated and is therefore extinguished in its entirety. The Ostars counterclaims are outside this Courts subject matter jurisdiction and are therefore DISMISSED in their entirety, WITHOUT PREJUDICE.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

By the court (Long, J.)

Decision Sketch

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Not much of a shortcut, however. The two roads connect (Circuit Avenue, as its name suggests, is a semi-circle) two houses away.

[Note 2] Without that exception, mortgages and leases would clearly have come within the term conveyances. Real Estate Bar Assn for Mass., Inc., 459 Mass. at 519 (mortgage transactions, deeds and leases are conveyances).

[Note 3] M. G. L. c. 156C makes no mention of a limited liability company being required to make public its members and/or owner(s). A search via the Secretary of the Commonwealth, Corporations Division database resulted only in disclosure of the companys manager, Joseph T. Doyle, Jr.