PAUL DeNADAL and CECILE DeNADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

PAUL DeNADAL and CECILE DeNADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

MISC 07-356049

August 1, 2011

BRISTOL, ss.

Long, J.

DECISION

Introduction

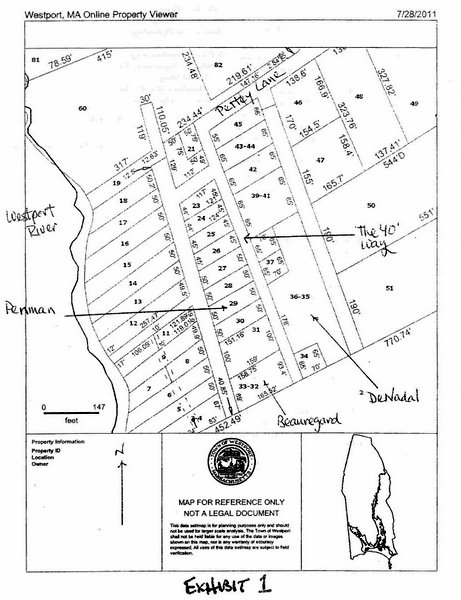

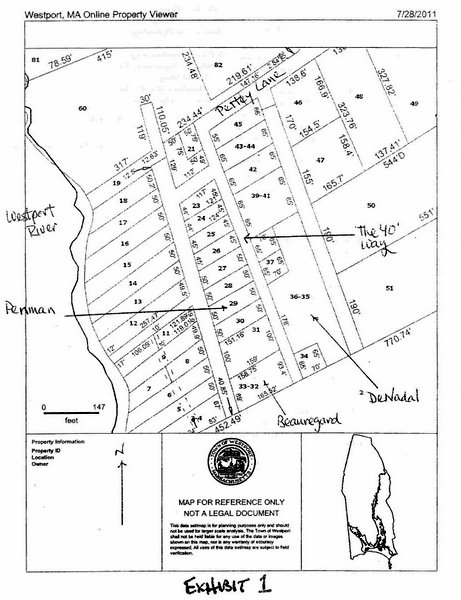

This is the second case to come before me, and the third before this court, concerning the 40'-wide private way (the "40' way") off Pettey Lane in Westport along which the parties' homes are located. [Note 1] The locations of those homes, the 40' way, and its neighboring ways are shown on the attached Exhibit 1. The parties do not contest their respective rights to use the 40' way for access to and from their homes. Nor do they contest their respective ownership of the fee interest to the mid-point of the way in its sections in front of their homes pursuant to the derelict fee statute. G.L. c. 183 § 58. What is contested, and very much so, is the extent of their rights, if any (1) to park on the section of the way directly in front of their homes (i.e., in the section whose fee they own), (2) to put objects or barriers on those sections, presumably to prevent anyone else from parking there, and (3) to park on the sections of the way directly in front of any of the other parties' homes. These issues were addressed in the earlier case before me as between defendants Philip and Kathleen Beauregard and plaintiffs Paul and Cecile DeNadal, and judgment was entered declaring:

[T]hat the [Beauregards] have the right to pass and repass over the portion of the 40' way owned by the DeNadals for the purpose of ingress and egress to the [Beauregards'] home, and for no other purpose; that they have no right to park on any part of the 40' way owned by the DeNadals; and that the DeNadals have the right to use their portion of the 40' way in any way that does not impair the Beauregards' right of ingress and egress.

Final Judgment, DeNadal I (Oct. 3, 2006). That judgment was affirmed on appeal, Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2008) (Mem. and Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28), [Note 2] and it precludes the re-litigation of any of the issues it addressed as between the Beauregards and DeNadals. See Massaro v. Walsh, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 562 , 564 (2008) ("The doctrine of claim preclusion makes a valid, final judgment conclusive on the parties . . . , and bars further litigation of all matters that were . . . adjudicated in the action.").

Defendant Maria Penman, who was not a party to DeNadal I, now asserts a right to revisit those rulings, seeking a different outcome for herself. What is also contested is a new (albeit related) issue between the Beauregards and the DeNadals, also joined in by Ms. Penman, regarding the extent of the parties' rights (if any) to re-locate the presently-improved part of the easement (the portion presently paved, which is not uniformly in the center of the way) [Note 3] and to pave whatever sections they choose in the remainder of the 40' way, regardless of who owns the underlying fee. [Note 4] There are also various trespass claims, the details of which are discussed

below. [Note 5]

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based upon the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule as follows.

Facts and Analysis

The DeNadal, Beauregard, and Penman properties are in the Pettey Heights subdivision in Westport, which rises above the East Branch of the Westport River. See Ex. 1. Access to the subdivision is from Pettey Lane, a public road which runs along the subdivision's northern edge. Id. There are three private ways running southerly from Pettey Lane roughly parallel to the river, each 40' wide, which provide access to the subdivision lots. [Note 6] Id. At issue in this case is the middle of those ways, labeled "the 40' way" on Exhibit 1 for ease of reference. Part of that way has been paved, although subsequent to the creation of the subdivision and not by the subdivision developer (Mr. Pettey). [Note 7] The current paving is not uniformly in the center of the way.

Plaintiffs Paul and Cecil DeNadal are the owners of subdivision Lots 35 and 36 as shown on Exhibit 1. They acquired these lots by deed from Rose DeNadal together, inter alia, with "the right to pass and repass" over the 40' way at issue in this lawsuit and the 40' way bordering the east of Lot 36. [Note 8] See Ex. 1. Defendant Kathleen Harrison-Beauregard is the record owner of Lots 32 and 33, where she and her husband, defendant Philip Beauregard, have a home. She acquired these lots by deed from Patrick Murphy together, inter alia, with "the right to pass over" the 40' way at issue in this lawsuit and the 40' way bordering the west of her lots. [Note 9] Defendant Maria Penman currently has a life estate in Lot 29 which she obtained from her sister, Janet Radcliffe, "[t]ogether with any and all rights of way from said premises over land now or formerly of one Pettey to the main highway." [Note 10]

The parties do not dispute that they each own the fee to the midpoint of the ways in the sections abutting their lots. See G.L. c. 183, § 58; see also Brassard v. Flynn, 352 Mass. 185 , 188-89 (1967) (mentioning of a way as a boundary in a conveyance of land is presumed to mean the middle of the way, if the way belongs to the grantor). None of the parties' deeds, nor any of the deeds in their respective chains, purport to grant the right to park in the 40' way or in any of the other private ways in the subdivision.

The Rulings in the Prior Litigation, and the Question of Whether Ms. Penman has any Other or Different Rights

The judgment in the prior case between the DeNadals and the Beauregards, affirmed in its entirety on appeal, declared that (1) the Beauregards "have the right to pass and repass over the portion of the 40' way owned by the DeNadals for the purpose of ingress and egress to the [Beauregards'] home, and for no other purpose," (2) the Beauregards "have no right to park on any part of the 40' way owned by the DeNadals," and (3) the DeNadals "have the right to use their portion of the 40' way in any way that does not impair the Beauregards' rights of ingress and egress." DeNedal I, Final Judgment (Oct. 3, 2006). Those rulings are final and binding on those parties. I apply them below in the context of the issues presented in this case, but first address the question whether Ms. Penman, who was not a party to DeNadal I, has any other or different rights.

Ms. Penman, like the others, may certainly park in the part of the way she owns so long as such parking does not interfere with the other parties' right of ingress and egress to their properties using the way. [Note 11] See Brassard, 352 Mass. at 189. It is not disputed that Ms. Penman has the right to use the 40' way for ingress and egress to her residence - the same right as the DeNadals and Beauregards. But a right to pass and repass - her only express right - does not include a right to park on the parts of a private way owned by others except for temporary stops incident to travel. See Opinion of the Justices, 297 Mass. 559 , 562 (1937). A right to park, not expressly granted, can only arise by implication or prescription. Ms. Penman asserts such rights, but did not prove them.

Ms. Penman contends that she has an easement by prescription to park on the opposite half of the way, i.e. the part whose fee is owned by the DeNadals. [Note 12] See Ex. 1. The applicable law is straightforward. As codified in G.L. c. 187, § 2, a claimant may be entitled to an easement by prescription respecting the land of another if the claimant can prove that his or her use has been open, notorious, adverse to the owner, and continuous over a period of no less than twenty years. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007). To succeed, the claimant has the burden of proving each of these elements. Id.

Ms. Penman claims that she has regularly parked on the DeNadals' side of the 40' way for more than twenty years. [Note 13] I do not find this credible. During trial, Ms. Beauregard testified that she has seen Ms. Penman's vehicle parked on the eastern half of the way (the part of the way abutting the DeNadals' property) only six or seven times within the past ten years. If Ms. Penman parked her car on the eastern portion of the way as often as she claimed during trial, then certainly Ms. Beauregard (even if only casually observing the neighborhood and way) would have noticed Ms. Penman's car parked more than six or seven times in the grassy area of the way abutting the DeNadals' property. Similarly, Mr. DeNadal testified at trial that while Mrs. Penman, did park her car on the eastern portion of the way from time to time, she did so only "on occasion" and "very rarely." Rather, according to Mr. DeNadal, Ms. Penman normally parked her car next to her house, and did not begin to park on his half of the way until 2004. While "continuous use" does not mean "constant use," Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870), it certainly means more than "sporadic use." See Rivers v. Town of Warwick, 37 Mass. App. Ct. 593 , 597 (1994) (finding that "sporadic use" of discontinued public roads did not satisfy the use requirement for a prescriptive easement). As such, since I am not persuaded that Ms. Penman has parked her car on the eastern part of the way more than sporadically within the past twenty-odd-years, I find that Ms. Penman has failed to prove that she has a prescriptive easement to park on the eastern half of the way. See Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009) ("If any element [of a prescriptive easement claim] remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail.") (emphasis added).

Ms. Penman also asserts that she has an easement by implication to park on the eastern half of the way arising from the alleged intent of the original grantor and developer of Pettey Heights, David L. Pettey, to grant parking rights to all of the residents of the subdivision in all of the private ways. She admitted, however, that she never knew Mr. Pettey, and could point to nothing he ever said or wrote that indicated his intent to grant a general parking easement on the subdivision roads. Nor do any other facts support her claim.

The standard for an implied easement was articulated in Harrington v. Lamarque, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 371 , 375 (1997).

Implied easements, whether by grant or by reservation, do not arise out of necessity alone. Their origin must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable. Additionally, reasonable necessity is an important element to consider in determining if it was the presumed intent of the parties to a deed to create an easement.

(emphasis added) (internal citations omitted). Unlike Harrington and similar cases, there are no circumstances here from which an implied easement to park can be inferred. First, the deed language contains no reference to parking rights. Second, there are no specific characteristics of the subdivision lots that would suggest such an intent. To the contrary, as previously noted by the Appeals Court in its affirmance of DeNadal I, the lot sizes and corresponding available parking are not unique compared to other subdivisions where the general rule (that a right to park on a private way does not exist when the only right expressly granted is to pass and re-pass) applies. Appeals Ct. Mem. & Order at 4. Third, unlike Harrington, the way does not lead to an important community recreation area whose enjoyment requires nearby parking. Instead, it dead-ends at the Beauregards' house. Fourth, there is no "reasonable necessity" for Ms. Penman to park on the eastern half of the way. As established at trial, there is ample room for Ms. Penman to park her vehicle either on her lot proper or on her portion of the way. [Note 14] Fifth, even if the lot owners on the western side of the 40' way now customarily use the eastern half for parking (a claim by Ms. Penman which I do not find credible), "[c]ustom and usage that evolved after the original grantor conveyed the properties is little evidence of the grantor's . . . intent, particularly when the [Pettey Heights] subdivision was created 'decades' ago." Appeals Ct. Mem. & Order at 4. For these reasons, I find no basis for determining that Ms. Penman has an easement by implication to park on the eastern half of the way based upon the "presumed intention" of Mr. Pettey or otherwise. [Note 15]

In sum, Ms. Penman's rights in the way are identical to the DeNadals' and the Beauregards as previously declared in DeNadal I.

The Application of those Rights to the Present Controversies

The Defendants' Request that they be Allowed to Park In the Portions of the Way Owned by Others

As explained above, none of the parties have the right to park in any portion of the way whose fee is owned by others, except for temporary stops incident to travel. See Opinion of the Justices, 297 Mass. 559 , 562 (1937).

The DeNadals' Request that the Beauregards' and Ms. Penman Be Barred from Entering onto the Eastern Eleven Feet of the 40' Way; and the Defendants' Request That They Be Allowed to Pave All or Any Portion of the Full Width of the Way

The DeNadals ask that judgment be entered declaring that none of the defendants have the right to enter onto the eastern eleven feet of the private way abutting the DeNadals' property to the east, and for the right to place objects in that portion of the way to prevent such entry or use. The defendants request judgment that they may pave all or any portion of the full width of the 40' way, regardless of who owns the underlying fee. Both of these requests are too broad.

As noted above, the parties each have the right to pass and re-pass over the way for access to their homes. As the law makes clear, they may use the full width of the way for this purpose when "reasonably necessary," and may not when it is not. See Tehan v. Sec. Nat'l Bank, 340 Mass. 176 , 182 (1959) ("In the absence of express limitations, . . . a general right of way obtained by grant may be used for such purposes as are reasonably necessary to the full enjoyment of the premises to which the right of way is appurtenant.")(emphasis added); Davis v. Sikes, 254 Mass. 540 , 547 (1926) (same); Guillet v. Livernois, 297 Mass. 337 , 340-41 (1937) (a party's right to make a way passable and usable for its entire width must be exercised "having due regard to the rights and interests of others....Whether improvements made are reasonable in view of the equal rights of others, is largely a question of fact.").

The way in question is 40' wide. Paving the entire 40' is not presently a necessary or reasonable improvement. It is a dead-end street and serves only a handful of homes. See Ex. 1. Traffic on the way is occasional and generated almost exclusively by those few properties along its length. Normal ingress and egress should not need more than the middle 20' of the way, which is more than enough for a lane each way. So far as the evidence showed, the town does not require anything more. If the present paved surface is in a different location, the parties may relocate it to the center, the parties seeking its re-location to bear that expense. Gillet, 297 Mass. at 340 ("The right of anyone entitled to use a private way to make reasonable repairs and improvements is well established. . ."). [Note 16] There may be emergencies (fire, police) or particular needs (e.g. over-sized construction cranes or vehicles) that require more than 20', but these will be rare.

Accordingly, the DeNadals may park in the immediately abutting 10' portion of the way whose fee they own, and may put easily removable objects in that area, but they may not install any permanent objects there. They may also re-locate any presently paved portion of the way in that 10' area to the center of the way, contingent upon their paying the full cost of that re-location (i.e. ensuring that the center pavement is 20' wide and merges easily and seamlessly with the other sections of the paved way; otherwise they must bear the expense of making it so, potentially including the cost of re-locating and re-paving the full length of the way if that is necessary to make its merger easy and seamless). [Note 17] The same ruling applies to the defendants with respect to the 10' portion of the way immediately abutting their homes and their right to re-locate any portion of the pavement in that 10'. The middle 20' of the way must remain completely un-parked upon and un-obstructed.

The DeNadals' Trespass Claims

The DeNadals claim that the Beauregards and Ms. Penman have trespassed upon their property on "multiple occasions" and that the DeNadals are thus entitled to injunctive and monetary relief as a result. [Note 18] It is well-settled that a trespass occurs when a person "enters .. . upon land in the possession of another without a privilege to do so." Gage v. Westfed, 26 Mass. App. Ct. 681 , 695 n.8 (1988). In order to prevail on an action for trespass, the claimant must make a two-part showing: (1) actual and lawful possession of the property by the claimant, and (2) that the defendant's entry was illegal. See New England Box Co. v. C & R. Const. Co., 313 Mass. 696 , 707 (1943).

Regarding the second component of this two-part test, [Note 19] the evidence shows that the Beauregards and their visitors have, on at least some occasions and without the DeNadals' permission, backed their vehicles through the way and onto the DeNadals' property. [Note 20] In doing so, the Beauregards and their visitors have damaged landscaping and fencing situated in the DeNadals' front lawn. It is immaterial whether the Beauregards' entry onto the DeNadals' lawn was intentional, negligent, or purely accidental. See J. D'Amico, Inc. v. Boston, 345 Mass. 218 , 224 n.6 (1962) (noting that a "[t]respass may occur from an intrusion by mistake"). A trespass simply requires an affirmative and voluntary act by the trespasser. See United Elec. Light Co. v. Deliso Const. Co., 315 Mass. 313 , 318 (1943). Driving is clearly an affirmative act, and there is no evidence from which to conclude that the Beauregards (or their visitors) had the DeNadals' consent to use their front lawn as additional turnaround space or reasonably believed they had such consent. Injunctive relief enjoining them from continuing to enter the DeNadal property shall enter accordingly. [Note 21]

Similarly, Ms. Penman has neither an express, implied, nor a prescriptive right to park her vehicles in the eastern half of the way except for temporary stops incident to travel. Her parking on the eastern half of the way thus constitutes a trespass upon the DeNadals' property, regardless of how sporadic or infrequent. An injunction enjoining Ms. Penman from continuing to park there shall enter accordingly.

This leaves the question of damages, which are denied for lack of specificity and proof. As noted in Lowrie v. Castle, "[damages] need not be susceptible of calculation with mathematical exactness, provided there is a sufficient foundation for a rational conclusion. But such damages cannot be recovered when they are remote, speculative, hypothetical, and not within the realm of reasonable certainty." 225 Mass. 37 , 51 (1916) (internal citations omitted); see Burnham v. Dowd, 217 Mass. 351 , 360 (1914). Here, the evidence of monetary damage was

insufficient to bring it within "the realm of reasonable certainty" and is accordingly denied. [Note 22] Lowrie, 225 Mass. at 51.

The DeNadals Are Not Entitled to Attorney's Fees Pursuant to G.L. c. 231, § 6F.

The DeNadals assert that "all or substantially all" of the claims, defenses, and counterclaims raised by the Beauregards and Ms. Penman are "wholly unsubstantial, frivolous, and not advanced in good faith." They accordingly ask that I award them "their reasonable attorneys fees and costs incurred by them" in having to defend against such claims pursuant to G.L. c. 231, § 6F. However, I find that the claims, defenses, and counterclaims raised by the Beauregards and Ms. Penman, while unpersuasive, were neither unsubstantial nor frivolous, nor do I find that the claims were advanced in bad faith. The DeNadals' request to be reimbursed their reasonable attorney's fees and other costs is thus denied.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons: (1) the parties may park in the 10' section of the 40' way immediately abutting their properties, (2) the parties may put objects or barriers in those sections, so long as they are easily removable and immediately removed when that 10' is "reasonably necessary" for access or egress to the other properties on the way, (3) no one other than the party that owns the underlying fee (or their invitees) may park in the 10' of the way immediately abutting that party's property, (4) the center 20' of the way must be kept open and unobstructed at all times, and (5) any party having rights in the way wishing to relocate any section of the current paving to the center 20' may do so, so long as they bear the full expense of such relocation (i.e. ensuring that the center pavement is 20' wide and merges easily and seamlessly with the other sections of the paved way; otherwise they must bear the expense of making it so, potentially including the cost of re-locating and re-paving the full length of the way if that is necessary to make its merger easy and seamless). In the meantime, the current paving must remain in its present location. Judgment shall enter accordingly. All of the parties' other claims are DISMISSED, WITH PREJUDICE.

SO ORDERED.

Keith C. Long

Justice

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The previous case before me was Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, Land Ct. Case No. 05 Misc. 316714 (KCL), 14 LCR 581 (2006), aff'd, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2008) (hereafter referred to as "DeNadal P"). The earlier consolidated cases of Murphy v. Tuckerman, Bristol Superior Court Civil Action No. 90-01557 and In re Registration Petition of the Susan Tuckerman Trust, Land Court Reg. Case No. 42931 (hereafter referred to as the "Tuckerman" case), were heard and decided by the late Chief Justice Robert Cauchon. Decision (Oct. 31, 1995) and Judgment (Oct. 31, 1995).

[Note 2] The Appeals Court's Memorandum and Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28 is hereafter referred to as "DeNadal I Appeals Court Mem. & Order".

[Note 3] Not surprisingly, the parties who wish to re-locate the pavement are the ones whose section of the way is disproportionately paved.

[Note 4] Again not surprisingly, the parties who wish such additional paving want the right to place it on the sections owned by others, not theirs'. In fairness, as owners of the fee in their section, they have the absolute right to pave it without need of any court declaration, perhaps explaining why such a ruling is not sought in this proceeding.

[Note 5] At the time of trial, the DeNadals also sought a declaration that the 40' way is only 30' in width, not 40'. This claim fails, for two reasons. First, it is in direct contradiction of the position they took in their verified complaint, the factual allegations of which are binding on them. G.L. c. 231 § 87; Verified Complaint at 1, p. 1 (Oct. 5, 2007) (describing the private way in dispute as "forty feet in width"). Second and more importantly, the prior action before me (to which the DeNadals were parties) determined the width of the way as 40', judgment was entered stating so, and that judgment was affirmed on appeal. DeNadal I, Final Judgment (Oct. 3, 2006), aff'd. 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2008). The DeNadals are thus precluded from re-litigating that issue, as are the Beauregards. See Massaro, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 564. Ms. Penman does not dispute that the way is 40' wide, nor do the Beauregards. See also the Decision (Oct. 31, 1995) and Judgment (Oct. 31, 1995) in the Tuckerman case (to which the DeNadals were parties) which found the way to be 40' wide.

[Note 6] The private way closest to the river (west of the way at issue in this lawsuit) is referred to in some deeds as "the 30' way." See, e.g, Deed, Murphy to Harrison-Beauregard, Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 5104, Page 242 (Aug. 9, 2001) at 243. Nonetheless, as shown by the evidence in this and the earlier cases referenced above (see n. 1), it too is 40' wide.

[Note 7] The evidence showed that the paving was done at some point after the subdivision lots along the way had been conveyed, and that it was done by the new lot owners, perhaps acting through an informal neighborhood association, in the location they chose.

[Note 8] Deed, Rose DeNadal to Paul and Cecile DeNadal, Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 2203, Page 093 (Sept. 8, 1988).

[Note 9] Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 5104, Page 242 (Aug. 9, 2001).

[Note 10] Ms. Penman first acquired Lot 29 by deed from James and Mary McCarthy dated May 17, 1984. See Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 1892, Page 120. The deed conveyed the property "[t]ogether with any and all rights of way from said premises over land now or formerly of one Pettey to the main highway." On December 29, 1994, Ms. Penman conveyed the property by quitclaim deed, "[t]ogether with any and all rights of way from said premises over land now or formerly of one Pettey to the main highway," to her sister, Janet Radcliffe. See Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 3411, Page 31. On December 26, 2003, Ms. Radcliffe conveyed a life estate interest in Lot 29 to Ms. Penman, "[t]ogether with any and all rights of way from said premises over land now or formerly of one Pettey to the main highway." See Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 6736, Page 154.

[Note 11] For this reason, and as discussed more fully below, Ms. Penman does not have the right to park in the center 20' portion of the way, but can park in the 10' abutting her property.

[Note 12] Neither in her pleadings nor during trial did Ms. Penman specify the scope of this alleged easement. It is well-settled in this Commonwealth, however, that "the extent of [an] easement so obtained is fixed by the use through which it was created." Glenn v. Poole, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 292 (1981). See Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 364 n.8 (2009) ("[C]ourts look at the use during the prescriptive period before defining the scope of the easement."). By her own testimony, Ms. Penman's alleged use of the private way for parking varied with the seasons. Thus, any resulting prescriptive easement must, of necessity, vary with the seasons. However, since Ms. Penman did not sustain her burden of proving that she has acquired an easement by prescription to park on the eastern half of the way at all, I need not and do not reach the question of the scope of the easement that would have been obtained had she done so.

[Note 13] Between 1984 and 1997, Ms. Penman claimed that she never parked next to her property. Rather, she claims to have always parked in the grassy area opposite her property, on the eastern half of the 40' way that abuts the DeNadal property. This is in direct conflict with Mr. DeNadal's testimony, and I do not find her testimony on this issue credible. It is simply not believable that Ms. Penman would always park on the opposite side of the 40' way and willingly traverse that distance, or even frequently do so, when she had the opportunity to park on the portion of the way directly abutting her own property. Various photographs presented during trial show Ms. Penman's car parked in front of her own house. There were none that showed her parking on the DeNadals' side, and certainly none that showed her doing so on anything like a regular basis.

[Note 14] Ms. DeNadal testified that she has seen four to five vehicles parked perpendicular to the Penman house at one time, in the area between the paved portion of the way and the edge of Ms. Penman's property.

[Note 15] In support of her claim, Ms. Penman contends that the presently paved section of the way is disproportionately on the western half, and argues that this shows an intention on the part of the original grantor and developer of Pettey Heights to grant rights on the eastern portion of the way for all residents to park. I disagree. As previously noted, Mr. Pettey played no part in paving the way. Rather, the way was paved in the 1950's by the subsequent lot owners in the location they chose. As noted by the Appeals Court, the actions of a group of residents long after the subdividing of Pettey Heights has no bearing on the "presumed intention" of the original developer, Mr. Pettey. Appeals Ct. Mem. & Order at 4. Moreover, there are many possible reasons for why the paving is disproportionately on the western side of the way (perhaps that side of the way was muddier; perhaps the residents on that side wanted shorter driveways or sidewalks; etc.). There was no testimony from contemporary lot owners to support Ms. Penman's argument.

[Note 16] As noted above, the pavement is in its present location by choice of the abutting lot owners' predecessors in title. Thus, the expense of any change to that previously-agreed location should be borne by the party seeking the change.

[Note 17] See n. 16. There was no evidence that any of the DeNadals' 10' was paved as of the time of trial, but I make this ruling in case that is no longer true, and to make clear that the ruling applies equally to all of the parties to this case. If there is paving in any portion of the 10' of the way immediately abutting their properties, they may re-locate that paving provided they bear the full expense of that relocation.

[Note 18] In their Joint Pre-Trial Mem., the Beauregards disputed this court's authority to award monetary damages. But see Ritter v. Bergmann, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 296 , 302 (2008) (noting that the authority of the Land Court to award damages is "clear where damages are ancillary to claims related to any right, title, or interest in land ...."). Here, the Beauregards' defense to the trespass claims was their assertion that they had a right to drive where they did - an assertion of a "right, title or interest" in the land affected. This court thus has the requisite jurisdiction.

[Note 19] It is not contested that the DeNadals are the "actual and lawful possessors" of Lots 35 and 36. See Bristol County (South) Registry of Deeds, Book 2203, Page 093.

[Note 20] I am not persuaded by the DeNadals' claim that Mr. Beauregard and his "unleashed animals" trespassed on the DeNadals' property on February 11, 2007. Nor do I find the Beauregards' admitted entry onto the eastern half of the way - to take measurements of the way - to be a trespass. See G.L. c. 266, § 120C. Similarly, while Ms. Penman admits having entered the DeNadals' property in order to capture her errant dog, she testified that she did so with the permission of the DeNadals. Since I find that Ms. Penman did have the DeNadals' permission to enter their property to capture her dog, her entry was not a trespass. Surely the DeNadals' can have no reasonable objection to Ms. Penman's pursuit and recapture of her dog, particularly when there was no evidence that she intentionally released her dog onto the DeNadals' property or that the dog's presence on that property is more than a sporadic, unintended occurrence.

[Note 21] There is some support for the notion that the Beauregards should not be held liable for their trespasses if their trespasses are found to be "unintentional and non-negligent." Edgarton v. H. P. Welch Co., 321 Mass. 603 , 612 (1947) (overruled on other grounds); Restat 2d of Torts, § 166. What significance these sources are to be afforded is not a determination I need to make as I find that the Beauregards' trespasses onto the DeNadals' property were intentional. The Beauregards claim that maneuvering their vehicles out of their driveway and positioning them so that they can be driven forwards down the way is difficult, especially when other vehicles are parked in the way. But this is a function of where and how they've chosen to park. There is more than enough room on their property, on the 10' of the way they own, and on the 20' of the way in the center, for them to pull in and out in a reasonable manner.

[Note 22] The DeNadals claimed that the fence the Beauregards damaged cost three dollars per section to repair, but did not state how many sections needed to be repaired or, if the DeNadals replaced the entire fence, why the Beauregards should be required to pay for an entirely new fence having only damaged a portion thereof. The DeNadals also claimed that they neither had "knowledge of any damage" nor suffered a "financial loss" as a result of the alleged February 11, 2007 trespass.

PAUL DeNADAL and CECILE DeNADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

PAUL DeNADAL and CECILE DeNADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN