HELEN TWARDOWSKI v. MICHAEL UKSTINS, HEATHER UKSTINS, ET AL

HELEN TWARDOWSKI v. MICHAEL UKSTINS, HEATHER UKSTINS, ET AL

MISC 09-412041

August 15, 2011

ESSEX, ss.

Grossman, J.

HELEN TWARDOWSKI v. MICHAEL UKSTINS, HEATHER UKSTINS, ET AL

HELEN TWARDOWSKI v. MICHAEL UKSTINS, HEATHER UKSTINS, ET AL

Grossman, J.

Introduction

By complaint filed on September 18, 2009, Helen Twardowski (plaintiff / Twardowski) initiated the instant appeal pursuant to G.L. c. 40A § 17. She seeks judicial review of a decision of the City of Salem Zoning Board of Appeals (Board) "sitting as the Variance Granting authority." [Note 1] The Board granted variances to defendants, Heather and Michael Ukstins (defendants / Ukstins), thereby allowing them to deviate from applicable parking stall dimension and setback requirements as set forth in Section 7-3 of the municipal zoning ordinance. [Note 2] The relief so granted allowed for the increase from two to four of the number of on-site parking spaces permitted in the yard behind the condominium which abuts plaintiff's accessory parcel. [Note 3]

On December 2, 2010, the Ukstin's filed a motion for summary judgment, pursuant to Mass. R. Civ.P. 56, seeking a disposition of this action "upon the ground that the undisputed facts of record, established in the plaintiff's deposition, prove that [Twardowski] is not a "person aggrieved" under Mass. Gen.L. c. 40A, sec. 17, and therefore is without standing..." [Note 4] A Summary Judgment Hearing was held on May 23, 2011, at which time this court took the instant matter under advisement. While making "all logically permissible inferences" from the factual record in favor of the plaintiff, [Note 5] Twardowski has failed to demonstrate that she, in fact, qualifies as a "person aggrieved" under M.G.L c. 40A § 17. As she has failed to carry her burden, [Note 6] this court is without subject-matter jurisdiction to consider the merits of the plaintiff's appeal. Thus, defendant's Motion for Summary Judgment must be granted.

Background

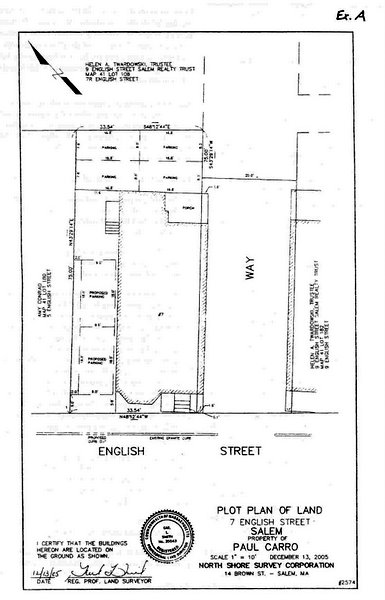

The plaintiff who is approximately eighty years of age, resides at 9 English Street, Salem, Massachusetts, a three family residential dwelling. The Ukstins are the owners of Condominium Unit No. 2 with deeded parking located to the rear of the building at 7 English Street, Salem. It is this parking area which is the focus of the instant matter. The parking area is approximately 33.54 feet by 16.6, and currently accommodates four parking spaces, i.e. it is a so-called stacked configuration with two spaces directly behind two others. [Note 7] Vehicles parked in the said spaces back out onto what is apparently designated Gerrish Way [Note 8] on the Plan of the North Shore Survey Corporation, captioned Plot Plan of Land 7 English Street, Salem, Property of Paul Carro (Plan), dated December 13, 2005. [Note 9] A copy of that Plan is attached hereto as Exhibit A. According to the Plan, 9 English Street, owned by the plaintiff and the site of her residence on the third floor, lies on the opposite side of the Way across from 7 English Street, the defendants' place of residence. [Note 10] While there are presently no residents on the first floor, plaintiff's brother-in-law resides on the second floor. [Note 11] The plaintiff also owns a parcel of land, designated 7R English Street, directly to the rear of, and abutting the parking area at issue.

Absent the variances granted by the Board, no more than two full sized spaces could be accommodated in the parking area.

Summary Judgment

Pursuant to Mass. R. Civ.P. 56 (b), "[a] party against whom a claim...is asserted...may, at anytime, move with or without supporting affidavits for a summary judgment in his favor...". Summary judgment must be granted when "pleadings, depositions...together with the affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ.P. 56 (c). Mass. R. Civ.P. 56 (e) provides, in relevant part, that the non-moving party "may not rest upon the mere allegations or denials of [her] pleadings, but [her] response, by affidavits or as otherwise provided in this rule, must set forth specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial..." [Note 12]

The moving party bears the burden of proving the absence of any genuine issue of material fact and that he is deserving of judgment as a matter of law. See Highlands Ins. Co. v. Aerovox Inc., 424 Mass. 226 , 232 (1997). In order to meet this burden,[11] the moving party need not proffer affirmative evidence negating the opponents claim, but can instead discharge that burden "by showing that there is an absence of evidence to support the non-moving party's case." See Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corporation, 410 Mass. 706 , 711 (1991). [Note 13] Stated differently, "the material supporting a motion for summary judgment...must demonstrate that proof of [an essential] element at trial is unlikely to be forthcoming" (internal quotations omitted) See Standerwick v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 35 (2006). [Note 14] Accordingly, if the record before the court shows that the standard for entry of summary judgment is met, then the motion should be granted. [Note 15]

Where the non-moving party merely relies on "bald conclusions," she is not thereby entitled to resist a motion for summary judgment. Catlin v. Bd. Of Registration of Architects, 414 Mass. 1 , 7 (1992). Here, the record reveals no genuine factual dispute, material under the law, which would preclude a legal determination of plaintiff's claim of standing. Consequently, this case is ripe for summary judgment.

It is well to note, at this juncture, that in their Joint Statement for Case Management Conference filed with the court on June 14, 2010, the parties recited the following:

As there does not appear to be material facts in dispute, the matter could be determined via motion for summary judgment.

Discussion

Only "persons aggrieved" by a local board's decision may seek judicial review of that determination under G.L. c. 40A, § 17. See Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996). In the absence of such aggrievement, this court is without the requisite subject matter jurisdiction and cannot therefore reach the substantive issues presented in plaintiffs' claim. See Marrotta v. Bd. of Appeals of Revere, 336 Mass. 199 , 202-203 (1957) ("the Superior Court had no jurisdiction to consider the case unless an appeal...was taken by an aggrieved person.") Ultimately, "standing to challenge a zoning decision is conferred only upon those who can plausibly demonstrate that a proposed project will injure their own personal legal interests and that the injury is to a specific interest that the applicable zoning statute, ordinance, or bylaw at issue is intended to protect." (emphasis in original) Standerwick, 447 Mass. 20 , 30 (2006).

"Parties in interest" entitled to notice of proceedings under G. L. c. 40, § 11, enjoy a rebuttable presumption of standing. Marrotta, 336 Mass. at 204. Once the presumption has been successfully rebutted "the point of jurisdiction will be determined on all the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiffs from the presumption as such." Marrotta, 336 Mass. at 204. At that juncture, plaintiff bears the burden to "demonstrate, not merely speculate, that there has been some infringement of [her] legal rights," Denneny v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Seekonk, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 208 , 211 (2003), and "that [her] injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33, quoting Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 132 (internal quotations omitted).

To rebut plaintiff's presumptive standing, the court may deem sufficient, evidence adduced in the course of discovery, including depositions and answers to interrogatories. [Note 16] See Bell v. Zoning Bd. F Appeals of Gloucester, 429 Mass. 551 , 554 (1999); See also Cohen v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Plymouth, 35 Mass. App. Ct. 619 , 622 (1993) ("we treat these submissions [of plaintiffs' depositions] as effectively challenging the plaintiff's standing...causing the presumption benefiting the owners of [the parcel in question] to recede." [Note 17] ). Plaintiff's presumptive standing will have receded once the defendant has either proffered evidence showing that a claimed basis for standing is not well founded, or alternatively, if the defendant can rely on plaintiff's lack of factual foundation for asserting a claim of "aggrievement." See Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35-36. [Note 18]

Once the presumption has been rebutted, the burden is on the plaintiff to demonstrate the requisite standing. See Barvenik v. Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132 (1992). Satisfaction of this burden requires both that the plaintiff "demonstrate, not merely speculate, that there has been some infringement of [her] legal rights," (emphasis added) Denneny v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Seekonk, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 208 , 211 (2003) and "that [her] injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33, quoting Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 132 (internal quotations omitted). Additionally, in order for such an injury to suffice as "aggrievement" under s.17, the harm must have been to "an interest the zoning scheme [sought] to protect." [Note 19]

In order to defeat a motion for summary judgment the plaintiff must proffer "credible evidence to substantiate [her] allegations." See Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. This evidentiary threshold has been characterized as "a plausible claim of a definite violation of a private right, a private property interest, or a private legal interest" (internal quotation omitted). [Note 20] However, the Butler Court suggests that the differing language is nothing more than semantic disagreement ("The two phrases are simply different ways of expressing the same concept [;] [a] plaintiff makes a plausible claim of a particularized injury by producing credible evidence of that injury." [Note 21] (internal quotations omitted)

In Butler, the court formulated a 'reasonableness test' concerning the production of credible evidence. See Butler at 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 441. ("Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made out [.. . .] Qualitatively, the evidence [must] be of the type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the board's decision.").

In Denneny, the court held that a plaintiff did not have standing where there was no evidentiary showing of § 17 "aggrievement" other than plaintiff's own "speculative and conclusory" testimony. [Note 22]

More recently, in Kenner, the Court sharpened the s.17 standing requirement when it held that "[a]ggrievement requires a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm." See Kenner at 459 Mass. 115 , 121 (2011). [Note 23]

As an abutting property owner, plaintiff is presumed to have standing to appeal the Board's Decision [Note 24] pursuant to G.L. c. 40A § 11. Nevertheless, her presumptive standing has been successfully rebutted. In this regard, the Ukstins have produced evidence in the form of plaintiff's testimony at deposition, which clearly demonstrates the absence of a factual underpinning for plaintiff's claims of aggrievement. Predicated upon her deposition, plaintiff's bases for aggrievement may, at best, be characterized as conjecture, hypothesis, speculation, or perhaps apprehension. In no instance has there been an adequate demonstration of particularized harm to the plaintiff's "private right, private property interest or private legal interest." In her complaint, plaintiff recites as follows in paragraph 17 thereof:

The Board of Appeals decision to grant the requested variances will cause the plaintiff to be subject to and suffer from traffic congestion, parking congestion, noise, exhaust pollution, light pollution, visual obstruction and will severely detract from the attractiveness, usefulness and monetary value of Plaintiff's property and otherwise detract from her quality of living.

In the course of plaintiff's deposition, defense counsel appears to have been guided by the foregoing list as he himself broached a number of the listed concerns.

Such concerns will be discussed, seriatum, below:

Traffic and Parking Congestion

Concerns about traffic or parking, when demonstrated with the requisite quantity and quality of evidence, and shown to be individualized, may suffice to confer standing under G.L. c. 40A § 17. [Note 25] See Nickerson v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Raynham, 58 Mass. App. Ct. 680 , 682, n. 3 (2002) (We ...recognize that traffic concerns are legitimately within the scope of the zoning laws.)

In Barvenik, the Court noted that "possible vehicular traffic increases [and] anticipated parking problems" were included within the ambit of "legitimate zoning-related concerns". [Note 26] However, if the plaintiff is to demonstrate, in adequate fashion, a traffic and/or parking based aggrievement, she is obliged to present credible evidence demonstrating that that the alleged traffic or parking congestion related concerns will cause a specific, particularized injury to her person or property.

In the course of her deposition, the plaintiff articulated traffic and parking-related concerns, as follows:

Tr. 15-16:

Q: Do you object to any of the parking spaces?

A :...Do I object to them? No.

Q: You don't?

A: I do. Yes, I do, because I would object because when I want to go over, if they want to back out, you've got four cars parked there .... And it does-it would interfere if I wanted to go over to my property.

Thereafter, when expressing the basis for her "objection to the variance" she responded as follows:

Tr. 21 It's a little bit of everything. It's to get there. I mean, it would interfere. It's a lot of backing in. There's four cars... I mean, you've got parked one in back of the other. I mean, one car or two cars would have to back out for another car to back out.

Tr. 22 I mean. There is-and it's dangerous. I mean, you have children that are living here. [Note 27] If there's children, you know, if they want to go over there and you have four cars. And all of a sudden, three people want to - three cars want to move and people want to go over there.

Tr. 31: If there are children in there, they could go from one place to another. They could go in that field. You wouldn't have the congestion of all the cars that are backing one by one. It would be stacked.

Tr. 32: I mean, like I say, the children, if there are children, in the house going even for anyone to go there.

Tr. 37: I mean, if you figure that - if you're going back with all these cars backing out, and what if somebody wanted to come in?

When asked specifically "Now how do you suffer from traffic congestion?" [Note 28] the plaintiff responded as follows:

Tr. 41: Well, traffic congestion? If they want to back out and if I want to pull in, or if I want to go over on to the other property, I mean, that would have something to do with it.

Tr. 43: And I mean, if one car wanted to get out and the other wanted to come out and I wanted to go in, I mean, that's congested.

Tr. 47: If I wanted to come in or somebody else that was visiting would like to come in and, you know, go park on my - you know, to the lot. If I want to turn my car around or whatever....

See the following exchange at Tr. 43:

Q: Do you have any photographs or visual evidence of that traffic congestion?

A: Of them going in and out? I've never seen-I'm not around that much you know. I don't stand out there and watch them.

See the following exchange at Tr. 42:

Q: Now have you retained the services of an expert for the purposes of this case who may support your traffic congestion theory?

A: You mean about them? No.

Q: Have you retained the services of any expert who would say that there is congestion in the neighborhood because of this variance?

A: I don't-no.

Perhaps most telling of all, is this exchange, also at Tr. 42:

Q: Have you seen any instances where there's been congestion out there?

A: Well, I haven't seen anything. (emphasis added)

The foregoing is noteworthy given the absence of factual support for the allegations concerning traffic and parking. Here, the defendants successfully challenged the plaintiffs presumptive standing and rebutted same by offering evidence derived from Ms. Twardowski's deposition. Once the presumption is rebutted, the burden rests with the plaintiff to demonstrate "by direct facts and not by speculative personal opinion that the injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community." See Kenner v. Zoning board of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 118 (2011), quoting Standerwick v. Zoning Board of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006). In Standerwick, the court took note of "our long-standing jurisprudence that standing to challenge a zoning decision is conferred only on those who can plausibly demonstrate that a proposed project will injure their own personal legal interests and that the injury is to a specific interest that the applicable zoning statute, ordinance or bylaw...is intended to protect. Id., p.30. It is this court's view that the requisite evidence was not forthcoming.

Diminution in Property Value

Plaintiff next claims to be aggrieved based upon an alleged diminution in property value. The following exchanges with Ms. Twardowski, are therefore relevant:

Tr. 30: Q: What do you think-that you feel would change if you are successful in your appeal to deny them [defendants] the benefit of the variance?

A: I would have the value of my house would be worth more.

Tr. 30-31: Q: If this case is successful, your appeal--- how will things be different for you?

A In other words, if they don't park there?

Q: How would things be different?

A: The value of my house would be worth more.

Tr. 52-53: Q: And have you any idea how much the presence of those cars detracts and decreases the value of your property?

A: Oh, I have no idea.

Q: The value now?

A: No. Well, I have no idea. I mean, I think if you have - the value of my property, if somebody had flowers or just a green lawn or just something, you know, the value of my property would be worth more...I'd be losing money because it doesn't look nice."

Q: Now did you hire any expert to speak to the issue...of the value of your property?

A: No I haven't.

Once again, plaintiff offers what may be characterized, at best, as pure speculation or opinion unsupported by any factual bases, whatever.

Increased Noise

In the course of her deposition Ms. Twardowski observed that if the defendants were unable to park four automobiles in the space allotted, "it would be less noise...." Tr. 31-32.

See also, the following exchange:

Tr. 44. Q: Now noise. What's the increased noise that will result if----

A: I hear bang. I mean, whatever. And I mean, don't forget... The beeping noise? Beep and the doors slamming.

Once again factual support of a substantive nature is wholly lacking. Even assuming, arguendo, that one could demonstrate some level of increased noise associated with the two additional parking spaces at issue, there is no evidence as to time or frequency of doors opening and closing, or with regard to the use of remote locking devices. [Note 29]

At best, such alleged harm, to the extent it exists at all, would be of a de minimus nature. See Kenner v. Zoning board of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 121 (2011)("[a]ggrievement requires a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm.") Predicated, moreover, upon the summary judgment record, it may not be said that such alleged harm is sufficiently particularized, inasmuch as the plaintiff resides on the third floor, across the street from the parking area. Simply stated, the plaintiff has not met her burden of proving aggrievement by direct evidence. Id. at 119.

Exhaust Pollution

Other purported aggrievements advanced by the plaintiff suffer from the same infirmities as do the harms discussed supra. In her complaint, Ms. Twardowski alleges that exhaust pollution occasioned presumably by the increased on-site parking, is a source of aggrievement. At her deposition, she testified as follows:

Tr. 39. Q: And you mentioned the word pollution.

A: They could start the car in the morning or whatever they do, they could keep running. And if they have children and the car is running, you have different---.

Tr. 46: Q: Exhaust pollution?

A: Well, that's in every car.... [S]ome cars may pollute more than others if somebody had an exhaust problem or something. I mean, there are other cars there, too. I mean some cars may pollute more than others if somebody had an exhaust problem or something.

Q: And you haven't hired any expert for this case?

A: No.

The plaintiff's expressed concerns regarding exhaust pollution are simply not grounded in fact. Moreover, that such concerns are not at all particularized is apparent from plaintiff's frequent references to children. [Note 30]

Light Pollution

In her complaint, the plaintiff referenced light pollution as the basis for aggrievement. At her deposition, following a somewhat confusing exchange regarding the source of any purported light pollution, [Note 31] the following testimony was adduced: Tr. 49.

Q: And do you currently suffer from light pollution?

A: Me?

Q: Yes.

A: Personally, no.

Q: But if the variance---

A: I live on the third floor....I think it would bother the people that are in the---yes, with those lights. [Note 32]

Tr. 51: Q: Have you hired any expert for this case that would speak to the issue of light pollution or-no? A: No.

While light pollution may have been referenced in the complaint, it is clear that the plaintiff does not claim to suffer its alleged ill affects, especially so, given the location of her third floor residence.

Aesthetic Considerations

In her complaint, the plaintiff noted that the variances granted by the Board will cause her to suffer "visual obstruction and will severely detract from the attractiveness." [Note 33]

In her deposition she offered the following testimony:

Tr. 31-32: Well, if they can't park four cars there, I mean, it would look...it would look better.

The following exchanges took place between the deponent and defendants' counsel:

Tr. 52-53.

Q: How is it that your property has been decreased in its attractiveness?

A: Decreased because you figure you have the four cars there.

Q: But how is your property less attractive to look at?

A: Well, how is it less attractive? Well, I mean, just it's not very nice to look at.

Q: Now did you hire any expert to speak to the issue of attractiveness...?

A: No, I haven't...

Tr. 51: Well, I mean, it's just looking at those four cars, the visual obstruction. It's not the - I mean, for all these years you saw grass and a nice empty space there and, I mean, flowers. And you look out there and you've got four cars. [Note 34]

Tr. 52: 17-21. "Decreased because you figure you have the four cars there...I mean, it's not very nice to look at."

As with the plaintiff's previous allegations of aggrievement, the record is wholly devoid of credible evidence that would support same. In any event, the Commonwealth's Appellate Courts have been loath to recognize purely aesthetic concerns as a cognizable interest under the zoning law. See Barvenik v. Board of Aldermen of Newton, , 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132-133 (1992). (Including "impairment of aesthetics or neighborhood appearance" in the list of "insufficient bases for aggrievement under Massachusetts law.") See also, Denneny v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Seekonk, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 208 , 213 (2008). ("anticipation that there will be aesthetic deterioration ...is beyond the scope of interests protected by the Zoning Act.") Lastly in this regard, see Martin v. The Corp. of the Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints, 434 Mass. 141 , 146 (2001) ("[g]enerally, concerns about the visual impact of a structure do not suffice to confer standing.")

It is well to note at this juncture, that the court possesses fairly broad discretion in determining those issues requiring expert evidence. See Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 36 (Affirming trial judge's determination that expert evidence was necessary to show substantial likelihood of increased crime and vandalism attributable to c. 40B development), citing Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 137 n. 13. In the matter at bar, this court concludes that expert knowledge and skill are required if one is to properly evaluate the impact of an alleged increase in traffic and parking. In similar fashion, expert testimony is required in order to demonstrate a diminution in the value of real estate flowing from the Board's decision. It would likely be required, as well, in order to demonstrate exhaust and light pollution. The summary judgment record is devoid of any indication that the plaintiffs themselves possess such expert knowledge or skill.

Typically, this court would require expert evidence on such matters, because these topics are generally "beyond the scope of the common knowledge, experience or understanding of the trier of fact without expert assistance." Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 138 n. 13 (stated in upholding trial judge's determination that expert evidence required on issue of traffic-based aggrievement). Nothing in the plaintiffs' presentation would warrant a deviation from this general principle.

In sum, plaintiff's own conclusory and speculative statements as to the nature of her purported aggrievements do not provide the credible evidence necessary to demonstrate standing. Further, issues including traffic and parking congestion, exhaust and light pollution, and diminution in value, [Note 35] are typically outside the realm of common knowledge and so require expert testimony of the sort that is lacking herein. [Note 36]

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I conclude that the plaintiff has failed to demonstrate the requisite aggrievement pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17. As a consequence, this court lacks jurisdiction to reach the merits of the instant appeal.

Accordingly, it is hereby

ORDERED that the defendant's Motion for Summary Judgment be, and hereby is ALLOWED.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

By the Court. (Grossman, J.)

Exhibit A

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Defendant, Zoning Board of Appeals for the City of Salem, filed its decision with the Office of the City Clerk, for the City of Salem on September 1, 2009. See Defendants' Statement of Uncontested Material Facts, p. 5.

[Note 2] Plaintiff's Appendix Exhibit B. Defendants' Statement of Material Facts at p. 9.

[Note 3] See Defendants' Appendix Exhibit B, Plaintiff's Opposition to Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment Exhibit D. ( The Petition for Variance was filed with the Board on July 28, 2009. The variance given from Sec. 7-3 of the zoning ordinance allowed the alteration of the rear parking area at 7 English Street from 22 feet with 2 foot setback to a stacked parking configuration of 7 x 16).

[Note 4] Plaintiff was deposed on September 16, 2010 (See generally Defendants Appendix Exhibit B), See Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment, p. 1, See also Defendants' Memorandum in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment.

[Note 5] Quoting Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991).

[Note 6] We clarify that the plaintiff always bears the burden of proof on the issue of standing. An abutter's presumption of standing simply shifts to the defendant the burden of going forward with the evidence." quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. 20 , 35 (2006).

[Note 7] See plaintiffs deposition, p. 12, in which she observed that "they [defendants] have a little yard there [in back] and they park in that little yard."

[Note 8] Tr. 20- 21.

[Note 9] Gerrish Way appears as WAY on the said Plan.

[Note 10] Defendants reside in Condominium No. 2 on the second floor of their building.

[Note 11] Tr. 49.

[Note 12] See Kourouvacilis, 410 Mass. at 713, citing Celotex Corp., 477 U.S. at 323-324 ("One of the principal purposes of the summary judgment rule is to isolate and dispose of factually unsupported claims and defenses, and we think it should be interpreted in a way that allows it to accomplish this purpose.").

[Note 13] Quoting Celotex Corp., 477 U.S. at 322.

[Note 14] Quoting Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 714 (1991), citing Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 328 (1986) ("It is enough that the moving party demonstrate [), by reference to material described in Mass. R. Civ. P. 56 (c), unmet by countervailing materials, that the party opposing the motion has no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable interest") (internal quotations omitted) Standerwick at 35, quoting Kourouvacilis at 716.

[Note 15] See FN 12, Supra.

[Note 16] In Bell, plaintiff's presumptive standing was effectively rebutted when "trustee's deposition testimony failed to show that the proposed project [would] impair any interests of the trustee that are protected by the zoning laws [.]" Id. at 554.

[Note 17] See Id. p. 621, "When standing is contested, the presumption recedes."

[Note 18] The Standerwick Court held that "[a] developer was not required to support his motion for summary judgment with affidavits on each of the plaintiffs' claimed sources of standing; its reliance on the plaintiffs' lack of evidence as to the other claims, obtained through discovery, had equal force" (emphasis added) Id. at 35-36.

[Note 19] Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 32.

[Note 20] Harvard Square Defense Fund, Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 493 (1989).

[Note 21] Butler at 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441 (2005); See also Bell at 429 Mass. at 553-554.

[Note 22] Denneny v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals Seekonk, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 208 , 213-214 (2003).

[Note 23] Kenner at 459 Mass. 115 , 122 (2011) ("The adverse effect on a plaintiff must be substantial enough to constitute actual aggrievement such that there can be no question that the plaintiff should be afforded the opportunity to seek a remedy." The Kenner Court also held that simply being impacted by a ZBA Decision is not enough, on its own to constitute § 17 "aggrievement".

[Note 24] Plaintiffs Appendix Exhibit C; Also, The Ukstin's petitioned the zoning board for variance to the parking stall dimension and setback requirements for the parking areas at both the front and rear of their property from Sec. 7-3 of the Salem Zoning Ordinance. However, the variance was granted only with regard to the rear parking area.

[Note 25] Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 722.

[Note 26] Barvenik, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 133.

[Note 27] There is no indication in the summary judgment record that plaintiff has specific children in mind in her frequent references to children. In the course of her deposition, when the plaintiff was asked specifically if she knew "whether or not any of the people in the condominium have children" she responded as follows: "I don't know... The Ukstins [defendants], I think they have a child." Tr. 39.

[Note 28] Tr. 41.

[Note 29] Presumably the source of the beeping sounds claimed by the plaintiff.

[Note 30] Other than the plaintiffs references to children, their presence in the neighborhood has not been demonstrated.

[Note 31] See Tr. 47-48. It is not at all clear whether the plaintiff is genuinely concerned with light pollution; if she is so concerned, it is not clear whether the alleged pollution derives from automobiles or from some sort of external lighting on a pole or a building.

[Note 32] The plaintiff testified that the first floor in her building is vacant.

[Note 33] See Complaint p. 17; See Plaintiff's Response to Defendant's Statement of Material Facts, pp. 4

[Note 34] During her deposition, Twardowski admits that the empty space containing flowers was changed to a parking area sometime between 2000 and 2007--when a Mr. Carro bought the adjacent property. This admission is evidence that the loss of aesthetic, by which plaintiff attempts to establish standing, was not actually or proximately caused by the Board's Decision to allow for increased on-site parking. Rather, the plaintiff's complaint of visual obstruction finds its causal connection with the purchase and decided use of the adjacent property, which pre-dates the Board's Decision to grant defendant's variance.

[Note 35] While not referenced in her complaint, plaintiff appeared to raise safety-related issues in her deposition. Suffice it to say, once again, that there was no factual underpinning for these allegations. The allegations, such as they were, were in no way particularized to the plaintiff or her property. Moreover, this court believes that such issues lie beyond the realm of common understanding, thereby requiring expert testimony. None was forthcoming.

[Note 36] Further, while plaintiff broached the issue of encroachment in her deposition testimony, critical factual detail and support was lacking. Even were it otherwise, the principle enunciated in Kenner, supra, would come into play insofar as there must be a showing of more than "minimal or slightly appreciable harm."