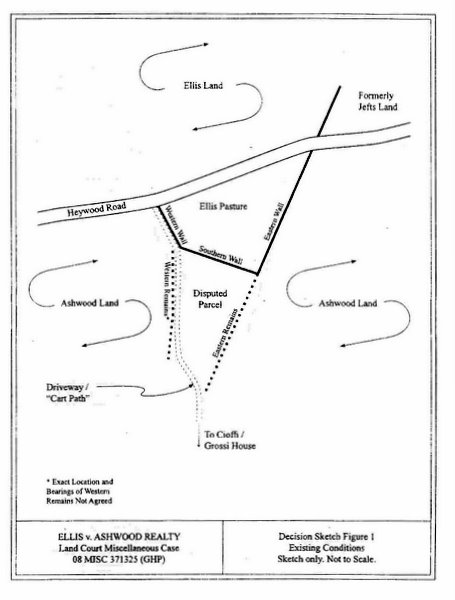

In this case I am called upon to decide which of the owners of two neighboring properties holds title to a certain parcel of land (the Disputed Parcel) situated between their respective real properties in Ashby, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Plaintiffs Scott T. Ellis and Susan G. Ellis, owners of a farm on Heywood Road in Ashby (the Ellis Land), claim that the Disputed Parcel is part of their farmland, by virtue of senior title rights in a chain of title traced back to an 1874 deed. Defendant Ashwood Realty LLC, a real estate development concern that has purchased and subdivided land (the Ashwood Land), formerly farmland, near the Ellis Land, and which has built an access driveway through the Disputed Parcel, disputes Plaintiffs interpretation of the 1874 deed, and asserts that the Disputed Parcel never has been part of the Ellis Land. The general location of the Disputed Parcel, and its orientation to the nearest parts of the parties other lands, is as shown, in a general way, on the attached sketch, Decision Sketch Figure 1. This area of the Disputed Parcel and the nearby surrounding parts of the lands of the parties, I refer to as the Locus.

Ashwood further claims that, even if the Ellis Land did once include the Disputed Parcel as a matter of record, title to the Disputed Parcel was subsequently acquired, by adverse possession, by Ashwoods predecessor in interest. At a minimum, Ashwood says that there exists, appurtenant to the Ashwood Land, an easement by prescription to access the Ashwood property over a preexisting cart path through the Disputed Parcel. Defendants Paul Cioffi and Cynthia A. Grossi have purchased, and built a house on, one parcel (Cioffi Lot) of the larger Ashwood Land subdivided by Ashwood. The Cioffi Lots title is secure--none of the parties claim the Cioffi Lot forms part of the Disputed Parcel. However, the driveway connecting the Cioffi Lot with the street, Heywood Road, does cross the Disputed Parcel, and Cioffi and Grossi ask for judicial recognition of their right to continue using this driveway to access their house. They claim rights by virtue of an easement by grant from Ashwood, but also assert that even if Ashwood never was the owner of the Disputed Parcel, and therefore could not grant an easement over it, their easement rights arise from the historic use of the cart path.

The Plaintiffs filed their complaint on February 19, 2008. At the same time, the Plaintiffs moved for judicial endorsement of a memorandum of lis pendens. I held a hearing on February 28, 2008, at which all parties appeared, and allowed the motion. The Defendants filed a special motion to dismiss, which I granted on May 1, 2008, finding that the Plaintiffs had failed to show possession of the Disputed Parcel as required in an action under G.L. c. 240, § 1, and therefore could not sustain an action under that statute. However, I stayed entry of judgment pending the promised filing of Plaintiffs amended complaint. The Plaintiffs filed a motion to amend the pleadings on May 13, 2008, which I granted. The Plaintiffs, in their amended complaint, sought declaratory judgment under G.L. c. 231A, to quiet title under G.L. c. 240, § 6 et seq., and equitable relief under G.L. c. 185, § 1(k). With these amendments in place, and the grounds for allowance of the special motion to dismiss no longer viable, the case proceeded to trial. Following discovery, a trial was held during which I heard the testimony of eight witnesses. Following trial, I took a view of the Locus. I received post-trial briefs and requests for findings and rulings, and later heard closing arguments on the record. I now decide the case.

After trial, on all the evidence I credit, for the reasons given below, I find and rule that the Plaintiffs hold title to the Disputed Parcel, that an easement by prescription exists appurtenant to the property of Defendants Cioffi and Grossi, but that the scope and extent of this easement is insufficient to support Defendants current and proposed uses.

On all the testimony, exhibits, stipulations, and other evidence properly introduced at trial or otherwise before me, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, and taking into account the pleadings, and the memoranda and argument of the parties, I find the following facts and rule as follows:

Findings of Facts

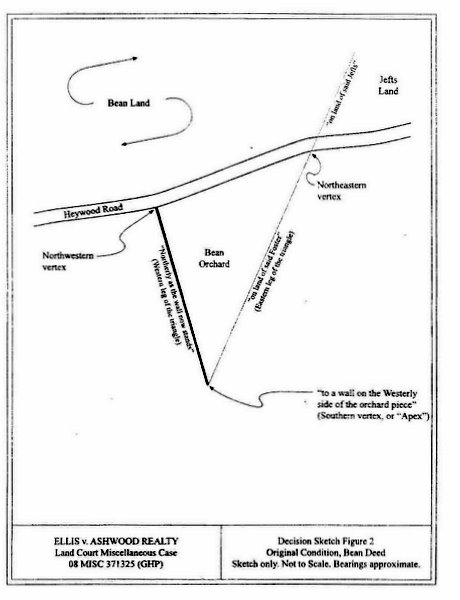

Both parties tracts of land once were owned by one Jesse Foster, who, having acquired a large holding from the estate of Pyam Burr [Note 1] divided this land into two parcels. The first parcel, conveyed to William H. Bean in 1874 and recorded May 28, 1878 [Note 2] (the Bean Deed), is the parcel located primarily to the north but partly to the south of Heywood Road and is the root deed for the Ellis land. The second parcel, conveyed to Joseph Davis in 1877 and also recorded in 1878 [Note 3] (the Davis Deed), is a parcel south of Heywood Road and abutting the western boundary of the southern portion of the Ellis property. The Davis parcel is now owned by the Defendants. Foster had previously conveyed a parcel to Sarah A. Jefts in 1868 [Note 4] (the Jefts Deed), lying to the north of Heywood Road and abutting the eastern boundary of the Ellis property.

Plaintiffs Chain of Title

Until the conveyance to Bean, Jesse Foster owned title to all of the Bean and Davis lands, including the Disputed Parcel. The Ellis land is a portion of that Foster land, which Foster conveyed originally to Bean. The Ellis Land was conveyed as follows:

May 28, 1878: [Note 5] Jesse Foster to William H. Bean, at Book 1477, Page 455

1886: Bean to Clinton W. Demont, at Book 1742, Page 283

1887: Demont to Luther J. Lawrence, at Book 1802, Page 445

1899: Lawrence to Orrin D. Prescott, at Book 2737, Page 385

1903: Prescott to Augustis S. Keyes, at Book 3063, Page 469

1910: Keyes to Leverett W. Ells and Nelson N. Hart, at Book 3522, Page 545

1919: Hart (1/2) to Leverett W. Ells, at Book 4244, Page 404

1927: Eva E. Hart, sole heir to Leverett W. Ells, to Ralph C. Davis and Doris T. Davis, at Book 5159, Page 164

1935: Davis to Ralph E. Buckwold and Pauline Buckwold, at Book 5961, Page 555

1942: Buckwold to Ernest S. Johnson and Alma E. Johnson, at Book 6631, Page 453

1947: Johnson to Gorham H. Wilbur and Helen D. Wilbur, at Book 7209, Page 115

1952: Wilbur to Edgar C. LeBlanc and Florence M. Leblanc, at Book 7934, Page 414

1979: LeBlanc to Scott T. Ellis and Susan G. Ellis, at Book 13627, Page 11

The portion of the Bean Deed that is directly relevant to the dispute I must decide reads as follows:

...thence Southerly on land of said Jefts to the first named road, thence across said road in a Southerly direction on land of said Jesse Foster to a wall on the Westerly side of the orchard piece, so called, thence Northerly as the wall now stands to the first named road...

The Jefts abutter call locates the eastern boundary of the northern portion of the Bean/Ellis land at a bound fixed in the Jefts Deed as South 53 ½ degrees West to Heywood Road. This course, carried and projected across Heywood Road, becomes a nearly perfect match for the eastern boundary of the Pasture, [Note 6] defined and described below.

As the land was conveyed down the chain of record title, certain scriveners errors were introduced. The 1886 deed replaces thence across said road in a Southerly direction on land of said Jesse Foster with thence across said road in a Northerly direction on land of said Jesse Foster. (Emphasis added.) This error remained in later instruments until the description was redrafted in 1935. The 1899 deed replaced to a wall on the Westerly side of the orchard piece with to a wall on the Northerly side of the orchard piece.

The writer of the 1935 deed redrafted the property description. The relevant portion then read:

...thence southerly along said Mulsi land and land formerly of Sarah A. Jefts, now of one Heywood, to said Heywood Road; thence across said road in a southwesterly direction by land formerly of Oliver Foster, now of one Keyes, to a wall on the southerly side of the Orchard Piece, so called; thence westerly and northerly along said Keyes land as the wall now stands to said Heywood Road...

This portion of the description has not changed since then.

Each deed in the chain contains the description being the same land or premises conveyed by the previous deed. [Note 7]

Defendant Ashwoods Chain of Title

Defendant Ashwood Realty, L.L.C., [Note 8] a Massachusetts limited liability corporation, acquired its Heywood Road property by quitclaim deed from Theresa B. Philbrick, widow of Oren E. Philbrick, in 2006. [Note 9] In 2007, Ashwood created eight lots out of this land, reserving 48.64 acres of remaining area, [Note 10] and conveyed one lot, Lot 1A on the Ashwood subdivision plan (Exhibit 70), to defendants Cioffi and Grossi, in 2007. [Note 11] Cioffi and Grossi since have built a single family house on Lot 1A, the Cioffi Lot.

The Defendants alleged record interest in the Disputed Parcel arises from the Foster to Davis conveyance. Defendants present the following chain of title:

1878: [Note 12] Jesse Foster to Joseph Davis, at Book 1464, Page 346.

1909: Alice M. Davis to Henry B. Boynton, at Book 3568, Page 261.

1909: Alice M. Davis to Albert H. Wilson, at Book 3568, Page 262. [Note 13]

1911: Boynton and Wilson to Fred E. Robbins, at Book 3577, Page 515.

1919: Julia A. Robbins to Vera M. Keyes, at Book 4285, Page 130. [Note 14]

1954: Vera M. Keyes to Alfred N. Ouellette and Julia K. Ouellette, at Book 8286, Page 591

1955: Ouellette and Ouellette to Oren E. Philbrick and Therese B. Philbrick, at Book 8515, Page 276

2006: Theresa B. Philbrick to Ashwood Realty, at Book 48021, Page 588. [Note 15]

2007: Ashwood to Cioffi and Grossi. (Lot 1A, the Cioffi Lot, discussed supra.)

Additional Findings

I further find the following facts, based on witness testimony and exhibits admitted:

The two lines marked remains of wall on the plan which is Exhibit 10, located on the south side of Heywood Road, Ashby, MA are the remaining extensions of stone walls which formerly extended from Heywood Road in a generally southerly direction and partially delineate the boundaries of a triangular shaped parcel of land--described in the Ellis root deed, Exhibit 40, and the Ellis current deed, Exhibit 56-- referred to as the orchard piece.

The wall describing the eastern side of the parcel labeled N/F Land of Scott T. & Susan A. Ellis on the Whitman & Bingham plan [Note 16] (this parcel, the Pasture) and the collinear Remains of Wall on the same plan were built as a single, continuous wall and partially demarcate a property boundary. (The wall on the eastern side of the Pasture I refer to as the Eastern Wall; the collinear remains of wall as the Eastern Remains; and the wall and remains taken together as the Eastern Wall and Remains.)

The wall describing the western side of the Pasture and the Remains of Wall near its southern end on the same plan were built as a single wall and partially demarcate a property boundary. (The wall on the western side of the Pasture I refer to as the Western Wall; the remains of wall as the Western Remains; and the wall and remain taken together as the Western Wall and Remains.)

The southern wall (the Southern Wall) of the Pasture, which wall runs in a generally east-west direction between the Eastern Wall and Western Wall, is an interior wall, intended to enclose the cleared land of the Pasture, and is not a boundary wall of the orchard piece. [Note 17]

One apple tree stands on the Disputed Parcel.

A cart path exists passing from Heywood Road, over Ashwoods Lot #4, through a gap in the Western Remains, over the Disputed Parcel and continuing on Ashwoods Lot #1A. This cart path was used historically by Ashwoods predecessors in interest to access a hay field on what is now Ashwood land.

Discussion

Record Title

The location of a disputed boundary line is a question of fact to be determined "on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans, and the actual occupation and use[s] by the parties ..." Hurlbert Rogers Mac. Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). Where, as here, deed construction is a part of that analysis, the law provides:

... a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Moreover, when abutter calls are used to describe property, the land of an adjoining property owner is considered to be a monument.

Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004) (internal citations omitted). Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered. Other principles also guide me. In general, property descriptions in prior deeds in a deed chain take precedence over inconsistent descriptions of the same land in later deeds, for the simple reason that a grantor cannot convey more than he possesses. [Note 18] "No surveyor or court has authority to alter or modify a boundary line once it is created. It can only be interpreted from the evidence of where that boundary is located." C.M. Brown, et al., Brown's Boundary Control and Legal Principles § 2.6 at 32 (4th ed., 1995) ("Brown's Boundary Control"). "[O]ne who grants title to property to a second person can grant no more interest than what is owned." Id. § 3.1 at 33. In situations of doubt or ambiguity, however, subsequent conduct (most notably, lines of occupation) and later deeds are sometimes helpful in resolving that uncertainty, because property owners' descriptions and actions may be indicative of the originally intended grant, and those of their successors may mirror and follow them. See generally LaBounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 345 (1967) (where easement location not precisely defined, location and use of easement by owner of dominant estate, acquiesced in by owner of servient estate, deemed indicative of intent); Fulgenitti v. Cariddi, 292 Mass. 321 , 325 (1935) ("Acts of adjoining owners showing the practical construction placed by them upon conveyances affecting their properties are often of great weight"); Bacon v. Onset Bay Grove Ass'n., 241 Mass. 417 , 423 (1922) ("Where the intent is doubtful, the construction of the parties shown by the subsequent use of the land may be resorted to, if such use tends to explain or characterize the deed, or to show its practical construction by the parties, providing the acts relied upon are not so remote in time or so disconnected with the deed as to forbid the inference that they had relation to it as parts of the same transaction or were made in explanation or characterization of it.") (internal citations and quotations omitted); Abbott v. Walker, 204 Mass. 71 , 73 (1910) (prior owner's statements in disparagement or limitation of title admissible against those claiming under him); Brown's Boundary Control § 11.22 at 273 ("When there is certainty in the location of the boundaries of a parcel of land and when several surveyors would all locate the property in precisely the same place, improvements such as buildings and fences are usually treated as encroachments; but if the survey lines are uncertain from lack of control of known fixed monuments and several surveyors might place the lines in different places, the fences and improvements are probably better evidence of the original lines of the original parties").

Three conveyances from Jesse Foster are material to this case: the Jefts Deed, the Bean Deed and the Davis Deed. It is clear that first priority belongs to the Jefts Deed, second to the Bean Deed and third to the Davis Deed, because each of these three deeds is from the same grantor, and each makes an abutter call fixing a boundary to a boundary of the previously conveyed parcel. [Note 19]

It is well settled that a deed granted but not recorded is valid only against the grantor and any persons having actual notice of the conveyance. [Note 20] Such notice need not necessarily be by actual exhibition of the deed, but also may derive from intelligible information of a fact, either verbally or in writing, and coming from a source which a party ought to give heed to.... George v. Kent, 89 Mass. 16 , 18 (1863). It therefore follows that if a grantor conveys a parcel to a first grantee by a deed that remains unrecorded despite passage of a reasonable amount of time, and the same grantor subsequently conveys the same parcel to a second grantee, the second grantee may claim the superior interest; but if the second grantee had actual notice of the first conveyance, the first deed will be valid against the second grantee and the first grantee may claim superior interest. [Note 21] Such notice may be either express or implied. Farnsworth v. Childs, 4 Mass. 637 , 637 (1808).

In this case, the Defendants assert that the Davis Deed likely was recorded first, though the Plaintiffs correctly show that the Bean Deed was executed first. The Bean Deed was therefore valid against Davis if Davis had notice of the Bean Deed, either expressly or by implication. I find that Davis did have such notice. Davis purchased his parcel in 1877 and recorded the deed in 1878; Bean took possession of his land upon the strength of the 1874 conveyance. The Davis Deed references the boundary between Davis and Bean land by abutter call to Bean, and as the Defendants title examiner correctly notes, it is the Bean deed and not the Davis deed which sets the boundary between the properties. The Davis property description states, in relevant part, thence Easterly on said road to land of said Bean; thence Southeasterly by land of said Bean [Note 22] to land formerly owned by Levi Smith.... [Note 23]

Therefore, I find that because Davis had actual notice, express or implied, of the Bean deed at the time of the Foster to Davis conveyance, the Bean title is the senior and superior interest. The intent of the Davis Deed was to convey to Davis that portion of the holding Foster had acquired from Burr which had not been conveyed previously to Bean. Indeed, there is no other reasonable reading of the Davis Deed. If Foster and Davis did not have an understanding of the location of Beans property south of Heywood Road, the words used by them in the deed, thence Easterly along said road to land of said Bean, would have had no meaning.

The question of which party's chain of title includes the disputed parcel is addressed, therefore, by studying the Bean deed, with ambiguities resolved by examining extrinsic evidence. The Bean deed states, in relevant part,

...thence Southerly on land of said Jefts to the first named road, thence across said road in a Southerly direction on land of said Jesse Foster to a wall on the Westerly side of the orchard piece, so called, thence Northerly as the wall now stands to the first named road...

(emphasis added). This description would undoubtedly have provided the reader, at the time of the conveyance, with very clear instructions enabling him to walk the bounds of the Bean property: Having followed the Jefts property line, which is well defined in the Jefts Deed, in a southerly direction to what is now Heywood Road, cross the road and continue southward to a wall on the western side of the "orchard piece." Then turn and follow that wall northerly to the road.

The plot described is a triangle, having the road as its northern boundary. This triangle being in the southern part of a clockwise walk, the description moves generally east to west and the wall monument describes the western leg of the triangle, with the course from the road crossing to the southern extremity of that wall being the eastern leg. The wall being the western boundary of an orchard, it has been reasonably inferred by all parties that in 1874 an orchard of apple trees fell within the triangular plot described. We are therefore presented with four monuments, which, if their locations were known with certainty, would be determinative as to the location of the Bean property lines and of the record ownership of the disputed parcel. A sketch of the Bean orchard piece is provided in Decision Sketch Figure 2.

The Jefts property line and the road are still well defined and are not in dispute. The intersection of these is the northeastern vertex of the triangle, corresponding to the northern end of the Eastern Wall. The intersection of the road and the Western Wall is the northwestern vertex of the triangle. The parties agree on the starting point and direction of the eastern course, which is in line with the Jefts property line and is marked on the ground by the Eastern Wall and, the Plaintiffs argue, the Eastern Remains.

By the 1874 property description, the eastern course reaches the wall that is on the west of the orchard, makes a right turn and follows the wall to the road. If the 1874 location of the orchard and its western wall were undisputed, the length of the eastern course and precise location of the southern vertex and western course would be clear. They are not, and this is the crux of this dispute.

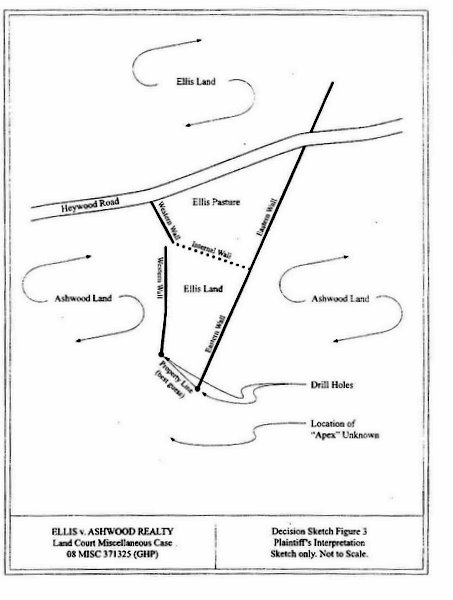

The Plaintiffs assert that the orchard, at the time of the Bean deed, included the entire triangle formed by adding the Disputed Parcel to the Pasture, and that the Western Remains are a portion of the original western wall. By the Plaintiffs' reckoning, that historic wall's southernmost point has been obliterated by the Defendants' driveway grading project, a plausible explanation given the substantially regraded surface condition I observed during my view of the Locus, and a factual finding which I adopt. By this understanding, the Western Wall and Remains is a portion of the western leg of the triangle. The northern end of the Western Wall is the northwest vertex, and the southern vertex lies somewhere to the south of the end of the Western Remains. The Plaintiffs have relinquished claim to the tip of the triangle, however, reserving their rights to the remainder of the Disputed Parcel. A sketch of the Plaintiffs claim is provided in Decision Sketch Figure 3.

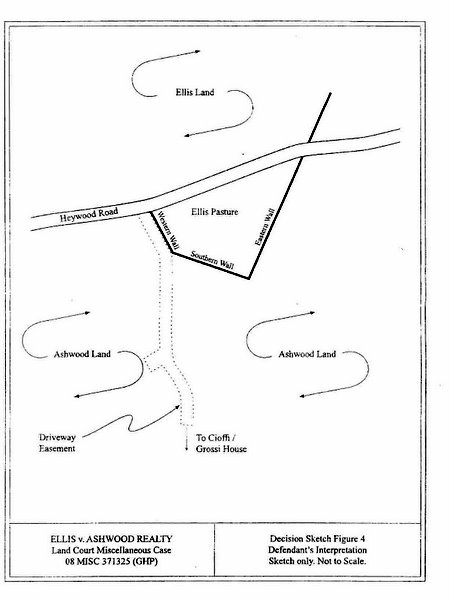

The Defendants, relying on other evidence on the ground, argue that the Bean Deed describes no triangle at all, but rather a four-sided parcel to the south of Heywood Road. In the Defendants' estimation, the Pasture is in fact the historic orchard. The road is its northern boundary, but the Eastern Wall, labeled on the survey plans as 159.72 feet plus 274.53 feet long and not inclusive of the Eastern Remains, is the entirety of the southerly course of the Bean deed. The point at the southeastern tip of the Pasture is then the southern vertex, and the Southern Wall, 260.15 feet long, plus the Western Wall, 152.68 feet long, taken together form the "northerly as the wall now stands" course. A sketch of the Defendants claim is provided in Decision Sketch Figure 4.

Based on the evidence on the ground and expert testimony and for the reasons discussed below, I find that the Plaintiffs present the persuasive and correct interpretation of the boundary. I find and rule that the Plaintiffs are the record owners of the Disputed Parcel.

The Plaintiffs have presented, properly, testimony of an expert who attempts to ascertain the historic origins and disposition of the walls located on the Locus using evidence currently on the ground. This expert, Dr. Thorson, a professor of geology with knowledge of archaeological geology and stone walls, whose testimony generally I find credible and reliable, describes at least two generations of wall. The Eastern Wall and Remains originally were one continuous wall. The Southern Wall is newer and of a different construction. The Southern Wall overlaps the Eastern Wall, and its weight causes the Eastern Wall to bow outward. The stones of the end of the Southern Wall are physically on top of stones of the Eastern Wall, showing that at the time the Southern Wall was added the Eastern Wall already existed. The relative age of the Western Wall is not determined, and if the Eastern and Western Walls did intersect in the past at the southern vertex that intersection (which Dr. Thorson refers to as the Apex) is now obliterated.

The Defendants counter with no evidence of the historic origins and disposition of the stone walls, though family members of the Defendants' predecessor in interest have asserted that the "remains of walls" are no walls at all but only piles of stones. That these piles happen to be arranged in straight lines, in line with or close to the lines of walls still existing; that barbed wire fencing predating the Philbricks ownership was found along the eastern wall remains; and that the Defendants' own surveyor apparently believes the stone piles to be "remains of walls," all remains unexplained. I find these witnesses' explanations to run against the weight of expert testimony and the evidence on the ground, and not to be credible. Stone walls are simply well organized piles of stones that may fall apart as time passes if the wall is not maintained. Some of the stones might be removed, as members of the Philbrick family describe doing, to allow easier passage of vehicles and equipment. Such decay and deconstructive activity may, over time, make a wall no longer apparent to a lay observer on the ground, but I find a surveyor and an expert inspector to be more reliable observers, and credit their testimony on this score.

The order of construction of the three walls can be inferred from a close reading of the Bean Deed, matched up with Dr. Thorsons conclusions. After crossing the road in a southerly direction from the corner of the Jefts land, the property description calls for a course in a Southerly direction on land of said Jesse Foster to a wall on the Westerly side of the orchard piece. [I]n a Southerly direction is not as the wall stands in a Southerly direction. No reference is made to the Eastern Wall, though monument calls to walls appear elsewhere in the property description. I conclude that no Eastern Wall existed at the time of the conveyance, but it was built later to mark the eastern leg of the triangle as a property line and to enclose that part of what is now the Ellis land. Of the walls now marking the Disputed Parcel, only the Western Wall existed in 1874. The Eastern Wall was added after that and the Southern Wall after the Eastern Wall. [Note 24]

The Southern Wall, being the last built, I find to be an internal wall entirely on Ellis land, which simply partitions the Pasture from the land behind it, which apparently went into disuse, and was not employed or needed as pastureland, at some time before the Ellis and Philbrick families took possession of their respective properties. [Note 25]

Lastly, the Plaintiffs attempt to address the question of the orchard location by presenting photographs of an apple tree and apples found within the Disputed Parcel and testimony that more such trees existed on the site in the past. This evidence is underwhelming, and insufficient to weigh heavily in favor of either partys claim. In 1874, there was an orchard somewhere within the triangle plot. It is not clear how long that orchard had existed, how old the trees were in 1874, how many apple trees ought to remain today, or the age of the lone tree still standing, though testimony does suggest that some of the trees may have been cut down as choice firewood. However, I do note that the Plaintiffs apple photos are the only physical evidence in the record that goes to the location of an orchard on the Locus generally, and therefore favor the Plaintiffs sense of the disputed boundaries.

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the Plaintiffs are the record owners of the Disputed Parcel.

Boundaries of the Disputed Parcel

Though the Ellises have shown that they hold record title to the Disputed Parcel, neither party has provided a survey that indicates precisely what the boundaries of that parcel are. To the north, the Disputed Parcel merges with the pasture and no boundary determination is needed because no ownership boundary exists. To the east, the centerline of the Eastern Wall and Remains marks the boundary. This line extends the boundary southerly until it intersects the 1874 centerline of the Western Wall; however, neither partys surveyor has plotted this western line.

Mr. Troupes has drawn an approximation of the parcel, with its boundaries being straight lines between surveyors drill holes; however, these holes were placed only recently by the Whitman and Bingham surveyors, to mark the conditions observed when Whitman and Bingham surveyed the Locus in preparing the Ashwood plans, and are not true indications of historic ends of the walls. The Western Wall itself has been damaged and cannot be traced to the Apex, and even its centerline is not plotted with precision. The Troupes survey notes centerline of stone wall difficult to determine. As Mr. Troupes correctly observes, it is a fact of geometry that when trying to locate the crossing point of two lines that meet at a very acute angle, as the legs of this triangle do, a small error in plotting one of the lines will be magnified to a large error in the placement of the point of intersection. The Western Remains are not straight, and Troupes does not know whether there might have been other turns in the original wall. To avoid substantial error he has plotted only what he found using currently existing monumentation.

I cannot accept that the walls as they now stand, in combination with straight lines traced between modern drill holes, are the best possible representation of the true boundaries of the Ellis property. The Bean deed describes a triangle; the survey plot does not show a triangle, the eastern leg course and the western leg course do not meet, and the western leg course is not plotted with precision. They are shown only graphically, and graphically they are not the same in the two survey plots. Further, based on Jimmy Boltons testimony, the northern end of the Western Remains may have been shifted due to the Philbricks stone removal efforts on the cart path. However, I am obliged to do the best I can to set these boundaries given the evidence I have. Therefore, I find that the boundaries of the Disputed Parcel, which is part of the Ellis land, are as follows:

Beginning at the drill hole marking the intersection on the eastern and southern walls of the Pasture, as shown on the Troupes plan (Exhibit 65 in this case, recorded at Book 13627, Page 011) and labeled S 54°09'15" W 274.53' and S 41°29'56" E 260.15' respectively, southwesterly by the course labeled S 53°53'08" W 428.42' on said plan to a drill hole, then northerly by the course labeled N 17°43'36" W 153.97' to a drill hole at the end of a wall remains, then northeasterly as the wall remains now stand to the end of said remains, then northeasterly to a drill hole marking the intersection of walls labeled N 03°57'33" E 152.68' and S 41°29'56" E 260.15', then southeasterly by land of Ellis to the first named drill hole.

Defendants Counterclaims

Adverse Possession

The Defendants claim that even if the Plaintiffs are the record owners of the Disputed Parcel, its title has been acquired by the Defendants predecessor in interest through adverse possession. To support this claim, the Defendants have introduced testimony by members of the family of Oren and Theresa Philbrick, previous owners of Ashwoods property, about activities that occurred on the Disputed Parcel. Specifically:

- The Philbricks daughter, Elaine Bolton, and her husband, the Philbricks son in law, Jimmy Bolton, testified that at various times the Philbricks cut wood on their land and used an area within the Disputed Parcel as a landing area, to which logs were brought and then split into firewood, which then was brought to the locations on the Philbrick property where it was needed.

- Elaine Bolton also described traversing the Disputed Parcel when picking laurel on the Philbrick property for making holiday decorations.

- Elaine Bolton testified that beehives had been placed on the Disputed Parcel with Mr. Philbricks permission. She did not have information on the owner of the beehives, on the magnitude or use of any profits generated from any beekeeping operation, or on the frequency or duration of the use of the beehives.

- Elaine Bolton and Jimmy Bolton testified that a quantity of disused equipment, truck parts and other items were located on the Disputed Parcel. This use had been ongoing since before the Philbricks took ownership of their property and ended when Ms. Philbrick brought in junk haulers from New Hampshire to remove the material.

It is well settled that to establish title by adverse possession to land owned of record by another, the claimant must show proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003) (quoting Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964)); Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 621-622 (1992); G. L. c. 260 § 21. The burden of proof in an adverse possession claim rests entirely on the person claiming title and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421 (quoting Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968)). If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968). Determin[ing] whether a set of activities is sufficient to support a claim of adverse possession is inherently fact-specific. Sea Pines Condominium III Assn v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 848 (2004).

The nature and extent of use required to establish title by adverse possession varies with the character of the land, the purposes for which it is adapted, and the uses to which it has been put. LaChance v. Rubashe, 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938); see also Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556 (1993) ([a] judge must examine the nature of the occupancy in relation to the character of the land.) (quoting Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992)). The claimant must demonstrate that he or she made changes upon the land that constitute such a control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership. Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556 (quoting LaChance v. First Natl. Bank & Trust Co. of Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488 , 491 (1938).

In Peck v. Bigelow, the Appeals Court held that a series of acts not extending to structural improvement, such as parking small vehicles such as mopeds for more than 50 years, mowing a small area of grass for 24 years, planting and maintaining trees for 10 years, "regularly" pruning branches, raking leaves, cleaning debris, and using a picnic table for 42 years, were insufficient to show adequate control and dominion over a vacant abutting lot. 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556. These uses were inadequate to prove adverse possession; the claimant made no permanent improvements on the lot and no significant changes to the land itself. Id.

Acts of ownership must be open and notorious so as to place the true owner on notice of the hostile activity of the possession so that he, the owner, may have an opportunity to take steps to vindicate his rights by legal action. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421 (quoting Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959)) (internal quotation marks omitted). To be open the use must be made without attempted concealment. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007); Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 420 (quoting 2 AMERICAN LAW OF PROPERTY § 8.56 (Casner ed. 1952)); Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955) (quoting 2 AMERICAN LAW OF PROPERTY § 8.56 (Casner ed. 1952)).

While the acts of possession must be open, proof of actual awareness on the part of the record owner is not required: To be notorious it must be known to some who might reasonably be expected to communicate their knowledge to the owner if he maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over his premises. It is not necessary that the use be actually known to the owner for it to meet the test of being notorious. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 420 (quoting 2 AMERICAN LAW OF PROPERTY § 8.56 (Casner ed. 1952)); Foot, 333 Mass. at 218 (quoting 2 AMERICAN LAW OF PROPERTY § 8.56 (Casner ed. 1952)). There is no requirement that the true owner be given explicit notice of adverse use, Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421, and if the use is open and notorious, it is deemed to place the true owner on constructive notice of such use, and it is immaterial whether or not the true owner actually learns of that use . . . . Id. Open and notorious use, however, must be continuous. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992) (stating that infrequent use does not satisfy a claim for adverse possession). Acts of possession that are few, intermittent and equivocal are insufficient to serve as a basis for adverse possession. Kendall, 413 Mass. at 624 (quoting Parker v. Parker, 83 Mass. 245 , ( 1 Allen 245 ), 247 (1861)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

The acts by Defendants predecessors in interest do not satisfy these requirements. The Boltons, Mr. Philbricks daughter and son in law, describe a pattern of mostly intermittent, infrequent and transitory uses. The Philbricks did not enclose, cultivate or improve the land. The only activities on the Disputed Parcel about which the Defendants have offered evidence as to continuity over a 20-year period are for passage across the Disputed Parcel (an activity which is transitory and non-exclusive, and goes to the prescriptive easement claim, rather than that for adverse possession), and firewood splitting. Defendants witnesses testified that the Philbricks harvested firewood each year, but they also testified that this harvesting took place across the entire Philbrick farm, and that the Disputed Parcel was only used for splitting when the wood was harvested from areas near the Disputed Parcel. The actual frequency of this activity on this particular site has not been established, and I do not find that it was at all frequent.

The only continuous alteration the Philbricks may have made to the Disputed Parcel was the addition of some junk and broken auto parts to a preexisting scrap heap, the origin of which is not established. [Note 26] If depositing a scrap heap on a site is a use that contributes to establishing title by adverse possession, which is not at all a certainty, it is of course the burden of the party claiming adverse possession to show who actually placed the scrap on the site, and when, and for how long, to thereby demonstrate who had used the site in this adverse manner. This the Defendants have not done. The junk pile could have been begun by Ellis predecessors, by Philbrick predecessors, or by some other party entirely. Occasional trespass onto anothers land and occasional addition to another partys junk pile is not sufficient to establish title by adverse possession.

I therefore find and rule that the Defendants have not established title to the Disputed Parcel by adverse possession, and that title to the Disputed Parcel therefore remains as I have found its record title to be--in the Plaintiffs.

Easement by Grant

A property may not be bound by an easement granted by a party who has no interest in that property. As defendant Ashwood never has held any interest in the Disputed Parcel, Ashwood cannot have granted a valid easement over that parcel. I therefore rule that the easement recorded at Book 50160, Page 478, September 28, 2007 and pertaining to Lot 1A and Lot 4 on Exhibit 70, is invalid and of no effect.

Easement by Prescription

An easement may be acquired by prescription through twenty years of continuous, open, notorious and adverse use. G.L. c. 187, § 2; Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 263 (1964); Nocera v. DeFeo, 340 Mass. 783 (1959). And the extent of the easement so obtained is fixed by the use through which it was created. Baldwin v. Boston & Me. R.R., 181 Mass. 166 , 168 (1902). Lawless v. Trumbull, 343 Mass. 561 , 562-563 (1962). [Note 27] See Dunham v. Dodge, 235 Mass. 367 , 372 (1920). Yet, the use made during the prescriptive period does not fix the scope of the easement eternally. See Lawless v. Trumbull, 343 Mass. at 563. It may change over time, and uses satisfying the new needs are permissible, "[b]ut the variations in use cannot be substantial; they must be consistent with the general pattern formed by the adverse use." Id. See also Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 173 (1948), which holds that once an easement is created, every right necessary for its enjoyment is included by implication.

Intermittent use of a right of way, or use that is disjointed in time, is insufficient to meet the requirement of continuous use. See, e.g., Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 (2007) (Plaintiff at times left the area for military service or to work out of state, breaking continuity). But seasonal or periodic use may be considered continuous, provided such activities demonstrate a pattern of regularity. See Stagman v. Kyhos, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 590 , 593 (1985) (noting pattern of regular use on weekends); Mahoney v. Hebner, 343 Mass. 770 (1961) (rescript) (holding seasonal absence did not prevent a finding of continuous use); Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961) (finding periodic use sufficient). In assessing the sufficiency of use, the question is whether the use would constitute adequate notice to the record owner that it should assert its rights to the property. See Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870); Boston Seaman's Friend Soc'y., Inc. v. Rifkin Mgt, Inc. 19 Mass. App. Ct. 248 , 248-249 (1985). It is not necessary to provide evidence of actual use during each year of the prescriptive period. Bodfish, 105 Mass. at 317.

In this case, the Defendants have shown a pattern of use over a period between 1956 and 1995 that I find sufficient to create an easement by prescription. During this period, the Philbrick farm included an area referred to as the Mountain, located behind the Disputed Parcel in and around the area now occupied by the Cioffi and Grossi house. The Philbricks used the Mountain continuously as a hay field, and accessed it by a cart path that began on Heywood Road between the Ellis Pasture and the pond shown on Exhibit 70, passed through Philbrick land next to the Pasture and then through the Disputed Parcel, and which continued back into Philbrick land to the Mountain. This cart path was sufficient for passage of pickup trucks, and was so used two to three times yearly for a few days at a time to harvest hay, once yearly to deposit fertilizer, and on occasion for firewood hauling. This use was infrequent, but it was repeated on a regular and periodic basis each year. The Philbricks sometimes maintained the path by removing large rocks and by depositing gravel after seasonal periods of heavy rain. This path was visible from the road, and was known to the community, being sometimes used by local troublemakers to access the hay field, so that for some period of time Mr. Philbrick attempted to control access to the path by stringing up a chain across the Heywood Road opening. Elaine Bolton describes this path as being twelve feet wide, which I find reasonable for the uses described. In addition to the vehicles, the path provided pedestrian access to family members who picked laurel on the Philbrick land during the holiday seasons.

There being a sufficient record of use of the right of way to establish an easement, it is now necessary to establish the extent of that easement. This analysis encompasses both the actual space occupied by the right of way and the character and amount of the use permitted. See Hoyt v. Kennedy, 170 Mass. 54 , 56-57 (1898) (easement by prescription must be confined to a particular and regular path and be for substantially the same purpose for which the way was designed originally); Glenn v. Poole, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 297 (1981) (increases in intensity of use permitted when consistent with general pattern formed by the adverse use). Exhibit 12, a plan recorded by Ashwood as Plan No 1054 of 2007, delineates an easement that is between 40 feet and 64 feet wide within the Disputed Parcel, which is owned of record by the Plaintiffs. The plan and the easement agreement, Exhibit 14, recorded at Book 50160, Page 478, which I have found invalid and of no effect, describe a driveway for two houses, along with utilities and drainage.

Though there is no dispute that the path of the driveway approximates the location of the cart path, it is clear that the width of the easement suggested by the Ashwood documents as well as the uses envisioned in them are well beyond the scope of the easement established by prescription. To claim an easement by prescription over a right of way, the Defendants must show use over the prescriptive period of the claimed width of the easement. Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009). Though some reasonable change in the character of the use is permissible, and it may certainly be that a change from pickup trucks accessing a field to cars accessing a home is consistent with the general pattern, as the law permits, I find that utilities and drainage are not consistent with the pattern established. [Note 28] A hay field requires no utilities or drainage, and I do not find that any such construction was reasonably foreseeable by the Philbricks or Ellises as part of the Philbricks use. Drainage and utilities require extensive excavation and construction work and maintenance of types not required for hay field access, and unless the drainage and utilities were to be located under the driveway itself they would fall outside the footprint of the easement on the ground. I therefore find and rule that utilities and drainage are not permitted under the easement established.

Further, there is the question of the amount of use to which the easement strip may be put. The Defendants have shown use a few times a year, for a few days at a time, by a small number of pickup trucks. By this characterization, the path was only driven on for ten to twenty days per year. This is materially less use than may be expected of a driveway that is the sole access to two single-family dwellings, occupied year-round. Such a driveway is used nearly every day, likely several times a day. In this generally rural area each adult in a household might be expected to own a vehicle which would use the driveway, in addition to any delivery or service vehicles, and those of guest and other invitees, needing access to the houses.

This amount of use can not be supported lawfully by the prescriptive easement established. There is no basis for the Cioffi and Grossi house, or a future house on Lot 4, to have a right of way to run their primary access ways over land belonging to the Ellises.

For the foregoing reasons, I now rule that there is a right of way, appurtenant to the properties labeled Lot 1A and Lot 4 on the Ashwood subdivision plan, that that right of way is available for occasional passage of vehicles over the strip used historically to cross the Disputed Parcel, and does not carry with it any right for utilities or drainage.

Laches

The Defendants also contend that the Plaintiffs are guilty of laches and cannot prevail for that reason. Laches is a legal doctrine holding that a legal right or claim will not be enforced or allowed if a long delay in asserting the right or claim has prejudiced the adverse party. Laches has been described as a method of defending against "legal ambush" and as "an equitable defense consisting of unreasonable delay in instituting an action which results in some injury or prejudice to the defendant." Yetman v. Cambridge, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 700 , 707 (1979). "It is well established that laches does not operate to bar a claim simply because the events which established rights in the plaintiff occurred long ago." West Broadway Task Force v. Boston Housing Authy, 414 Mass. 394 , 400 (1993). "Laches is not just mere delay, [however] it is delay that works disadvantage to another." A. W. Chesterton Co. v. Mass. Insurers Insolvency Fund, 445 Mass. 502 , 518 (2005). Whether laches has been established is a question of fact.

The Defendants, in asserting that the Plaintiffs claim is barred by laches, contend that Scott Ellis told Oren Philbrick in 1984 that he believed the Disputed Parcel was part of the Ellis land, but took no action. Further, Defendants say, after bringing his claim of ownership of the Disputed Parcel to the Defendants attention in 2006, before Ashwood purchased the Philbrick farm, Ellis took no further action until after Ashwood had purchased and subdivided the property and Cioffi and Grossi had purchased a lot and begun building.

I find that the Plaintiffs have not committed laches and that their claim is not barred. Mr. Philbrick is not a party to this action. Ellis and Philbrick took an agree to disagree stance in 1984, when neither was willing to pay the costs of a survey, title examination or court action, and mutually let the matter lie. The current Defendants cannot reasonably claim to have been prejudiced by this delay, as I find that Ashwoods principals were fairly informed of this dispute prior to their purchase of the Philbrick land. In 2006, when Ashwoods surveyor informed Ashwoods manager that Ellis claimed ownership of the Disputed Parcel, Ashwood had many options. Ashwood could have declined to purchase the property while title was in question, drafted an alternative plan of lot locations, or proposed a different driveway location so as to not rely on the Disputed Parcel. Ashwood could have collaborated with Ms. Philbrick to bring action to quiet title. Instead, Ashwood chose to proceed with the plan as conceived, placing a driveway on land to which Ashwoods principals were aware that Ashwood might not hold title. This was not an act of reasonable reliance, and Ashwood cannot now claim prejudice and ambush.

Cioffi and Grossi derive their title from Ashwood. They have no basis to claim delay against the Plaintiffs, who brought this action within a reasonable five months of Cioffi and Grossis purchase of their lot. As Cioffi noted in his testimony, he and Grossi were free to locate the driveway anywhere on his lot that they chose. I note that the Cioffi Lot, Lot 1A, has frontage on Heywood Road, as do all lots in the Ashwood development, and that Ashwood has additional land not yet subdivided, and has delineated potential locations for additional driveways accessing Heywood Road. Cioffi and Grossi also do not appear to have incurred significant costs improving the driveway until November of 2009, when they paved the driveway. This action was filed in February of 2008.

Finally, there does not appear to be any cognizable laches claim that would entitle the Defendants in equity to the relief they seek. Laches is a shield, not a sword. Sheriff's Meadow Foundation, Inc. v. Bay-Courte Edgartown, Inc., 401 Mass. 267 , 270 (Mass. 1987). The Plaintiffs are the record owners of the Disputed Parcel. The Defendants have never held title, and laches cannot aid one who never had title. Id. Laches does not assist a party in acquiring an easement over anothers land. Davenport v. Broadhurst, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 182 , 187-188 (1980). As I have noted, Cioffi and Grossi enjoy the benefits of an easement, however limited, to infrequent passage over the cart path; laches will not expand the scope this easement to include utility services, drainage or everyday passage.

Conclusion

Before judgment enters, I wish to afford the parties the opportunity to confer about the form the courts judgment should take, so as best to settle, of record, the disputed boundaries determined by this decision. I will direct entry of a judgment which fixes those boundaries as they appear here, unless, in response to a proper request, I receive a workable proposal to prepare promptly for the court a more detailed plan, entirely consistent with this opinion, to include more specific measurements and, if the parties so choose, a survey to locate the Apex and fix the true original boundaries, if that can be done without substantial error. If the parties decline this opportunity, then judgment will enter which simply employs the language above to describe this part of the Plaintiffs property based on the Troupes plan.

I request counsel to confer, and, within thirty days, to submit to the court a joint written report setting out the parties joint or several views on this question. If the parties agree that no new plan will be prepared, they are to submit one or two versions of what form the judgment ought to take. If there is a request for a new plan to be prepared, then the parties ought to advise the court in a comprehensive way about how they would have the plan prepared--who will do the work and who will bear its expense, and how long it will take to finish and submit. I will act in response to the report without further hearing unless otherwise indicated.

Judgment accordingly.

Gordon H. Piper

Justice

Defendants title examiner, John Troy, asserts this deed was recorded January 29, 1878. The copy of the deed in evidence is of poor quality; the J in the date is legible but the rest of the month is not, so that it might have originally read Jan. or June. The margin note reads June, but other indicators point to January, notably that the deed immediately above the Davis Deed in the photocopy of the registry book, Exhibit 21, is dated Jan. 29, 1878. If the Davis Deed was recorded in January, it was recorded before the Bean Deed; if it was recorded in June, the Bean Deed was recorded first. Though Troy is likely correct, it is unnecessary for me to find precisely the recording date of the Davis Deed. Such a finding might inform a decision under G.L. c. 183, § 4, were it not for Davis actual notice of Beans title. In the case now before me, the recording date is not dispositive. As discussed infra, Davis notice of Beans ownership and the Davis Deeds use of abutter calls to the Bean Deed have the effect of giving greater weight of priority to the Bean Deed, regardless of recording order.

The error is repeated in the 1986 drawing by Szoc Surveyors, a de bene exhibit in this case. Because that drawing is not signed or stamped, and no witness or evidence on record provides insight into whether any registered surveyor believed the walls shown to be property lines and what research, if any, may have contributed to such determination, the Szoc drawing can not be considered a true representation of property boundaries.

SCOTT T. ELLIS and SUSAN G. ELLIS v. ASHWOOD REALTY LLC, PAUL CIOFFI, CYNTHIA A. GROSSI and ENTERPRISE BANK AND TRUST COMPANY

SCOTT T. ELLIS and SUSAN G. ELLIS v. ASHWOOD REALTY LLC, PAUL CIOFFI, CYNTHIA A. GROSSI and ENTERPRISE BANK AND TRUST COMPANY