This matter comes before the Court on plaintiff's action

for rescission of a deed. The plaintiff is the grantee under a

quit claim deed from the defendants to lots 1, 2, 3, 4, Section

28, Division 2 of Standish Gardens in Plymouth, Massachusetts,

hereinafter referred to as locus. The defendants have brought a

third party complaint against Marguerite M. Hooley, the defendants'

predecessor in title; James M. Oates, Jr., the lawyer who drafted

the deed in the Hooley-Zegarelli transaction; and Lawrence DiLorenzo,

the real estate broker in the Hooley-Zegarelli transaction.

There appears to be two independent chains of title, both

going back over 50 years to a warranty deed before converging.

For convenience the two chains will be referred to as the Zegarelli

and the Hammond chain.

The Zegarelli chain of title traces back without difficulty

to a warranty deed from Corinda N. Sanford to Frank W. Chipman

dated January 13, 1916 and recorded in Book 1240, page 68. (Exhibit

No. 11), The Hammond chain of title traces back without difficulty

to a warranty deed from Rhodey F. Sturges to William H. Fessenden;

Fred A. Raymond, Fred Hatch and William B. Eaton dated December

28, 1883 and recorded in Book 501, page 543. (Exhibit No. 12, p. 12).

We know that the locus was a part of the land owned by the

Herring Pond Indians in 1870. Upon the petition of these Indians

the General Court appointed two commissioners who made partition

of the Indian lands. Pursuant to the deed of the commissioners

in the division of 1870, lot 49 of the Great Lot (which encompasses

locus) was set off to one Mariall Conant (Exhibit No. 12, p. 5).

The defendants Zegarelli trace their title from Mariall Conant

through intestacy, as their title examiner, Attorney June Prue,

found no references in the grantee indices for deeds of the locus,

into Corinda Sanford. The information linking Corinda Sanford to

Mariall Conant is provided by the Commissioners' Deed (Exhibit No.

12, pp. 1-5) considered in conjunction with Exhibit No. 17 which

is a deed from

"Ezra R. Conant, Rhoda F. Sturgis (formerly Rhoda F.

Conant), Carinda Sanford (formerly Carindia Hicks)

all of Marshpee .... and Alonzo Augustus Brown of Harrisburg

in the County of Dauphim and state of Pennsylvania"

to Arthur V. Curtis. This deed did not convey the locus but

rather a portion of lot 36 of the 1850 Herring Pond Indian Land

Division. However, it provides useful information in deciphering

the Conant family for it recites:

"Our title is derived from said William R. Conant sometimes

called William Conet and William R. Conet) who died about

1861 intestate, leaving a widow who is now Rhoda A. Sturgis,

one of the grantors, and two children, the older being Ezra

R. Conant, another of the grantors, and the younger being

Merrial H. Brown, formerly Merrial H. Hicks (also written

Mellie H. Hicks) who died intestate about 1896, leaving

no husband and two children, one of whom is Carindia

Sanford, another of the grantors, and the other of whom is

Alonzo A. Brown, the last of the grantors."

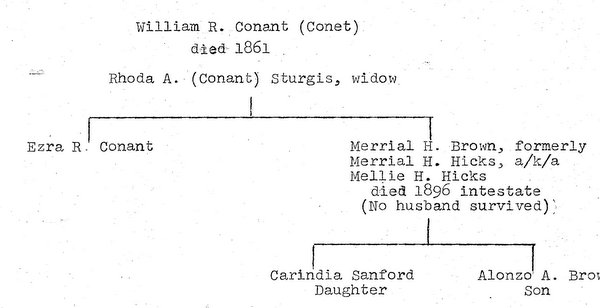

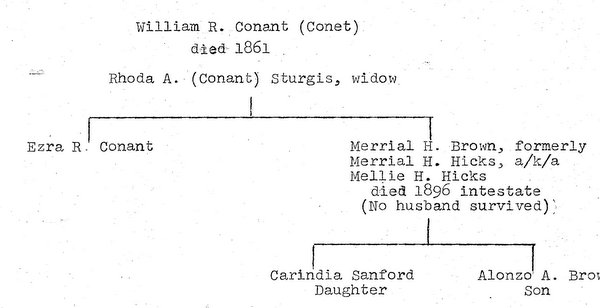

Converted onto a chart of a family tree it would look thus:

Merriall Conant is described in the Commissioners' deed (Exhibit

No. 12, pp. 1-5) as the minor daughter of William R. Conant of

Mashpee. Ezra Conant was listed therein as the minor son of

William R. Conant.

Considering exhibits 12 and 17 together, it could be concluded

that the Mariall Conant described in the Commissioners' Deed is

the Merrial H. Brown, Merrial H. Hicks and Mellie H. Hicks

described in Exhibit No. 17 and that Corinda N. Sanford is Carindia

Sanford, the daughter of Mariall. If Mariall Conant Hicks Brown

did not convey lot 49 of the Great Lot (locus) during her life,

then her two heirs, Corinda Sanford and Alonzo A. Brown, would have

inherited it. The defendants' title examiner found no probate or

death records for this Mariall Conant Hicks Brown under a number

of variations of spelling or for Alonzo Brown. Corinda N. Sanford,

as we have seen, conveyed this lot to Frank W. Chipman (Exhibit

No. 11) and thus by mesne conveyances it came to the defendants

Zegarelli. Thus, the Zegarelli chain depends upon intestacy and

noconveyanees out from Mariall Conant Hicks Brown.

However, it is arguable that Mariall Conant Hicks Brown did in

fact convey lot 49 of the Great Lot during her life and it is from

this conveyance that the Hammond chain traces. It has already been

noted that the Hammond chain proceeds from a deed from Rhodey F.

Sturgis to William H. Fessenden et al. (Exhibit No. 12, page 12).

This deed states in material part

"I Rhodey F. Sturges of Marshpee ... do hereby ... convey unto

the said Fessenden et al .....

...

In witness whereof, I the said Rhodey F. Sturgis, by Power

of Attorney from Melley Hicks hereunto set my hand and seal

this twenty-eighth day of December (1883).

(Emphasis supplied)

Signed, sealed and delivered, in presence of

Solomon Attaquin, Rhoda F. Sturgis seal, Merrial H. Hicks seal

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

Barnstable, ss. Dec. 28, 1883. Then personally

appeared the above named Rhodey F. Sturgis for Melley H.

Hicks and acknowledged the foregoing instrument to be

his free act and deed, before me

Solomon Attaquin, Justice of the Peace"

Thus, if this is a deed of Merrial H. Hicks and she is in fact the

Marriall Conant of the Commissioners' Deed, it is possible to trace

the Hammond chain also to the 1870 Division of the Herring Pond

Indians. The problem with this chain of title is that the deed to

Fessenden et al is indexed under Rhodey F. Sturges, not under

Hicks, Conant or Brown and that a power of attorney authorizing

Rhodey F. Sturgis to convey lot 49 of the Great Lot (locus) has

not been found recorded. There is a power of attorney (Exhibit

No. 16) dated April 30, 1883 and recorded in Barnstable County

Registry of Deeds on August 6, 1895 in Book 219, page 276 and

in Plymouth County Registry of Deeds on April 19, 1977 in Book 4257,

page 247 which states in material part:

"I Melley H. Hicks ... put Rhodey F. Sturgis, to be my

true and sufficient attorney for me and in my name

and stead, to enter in and settle the estate of my

Deceased Father and grandmother of whom I am an heir."

However, since Mariall Conant Hicks Brown owned lot 49 of the Great

Lot (locus) through the Commissioners' Deed and not through the

estate of her father or grandmother this power of attorney is not

applicable.

Thus, there are potential problems with both chains of title.

Were this an action to quiet title, the Court would have to consider

the effect of the absence of a recorded power of attorney, an

improper indexing of deeds, and the effect of other possible defects

in the chains of title. But on the view the Court takes of this

case the title questions are not material as the issue is a much

narrower one.

Testimony and evidence at trial centered on whether the

Zegarelli chain constitutes a good record or marketable title and

all parties have argued this point. However, plaintiff has merely

assumed a duty on the part of the defendants to deliver a good

record and marketable title and has never articulated any theory

under which the plaintiff would be entitled to recission at this

point in time for the defendants' failure to so do.

The plaintiff cites two cases in his brief: Jeffries v.

Jeffries, 117 Mass. 184 (1875) and Mahoney v Nollman, 309 Mass. 522 (1941). Both of these were actions for specific performance of

a purchase and sale agreement and state the principle that in a

proceeding for specific performance the potential purchaser will

not be compelled to accept a doubtful title, that is, one which

may reasonably be expected to expose the purchaser to litigation.

While a seller, by reason of the terms of a purchase and sale

agreement, may have a duty to deliver a good record or marketable

title, acceptance of a deed discharges the duties of the seller

except for those that are embodied in the deed. Pybus v. Grasso 317 Mass. 716 (1945). Since acceptance of the deed has occurred

here, it is necessary to consult the deed itself to determine the

duties of the defendants. The plaintiff's deed (Exhibit No.1)

contains quitclaim covenants, i.e., the defendants have covenanted

that the granted premises are free from all encumbrances made by

him and that he will defend against all persons claiming by, through

or under him. G. L. c 183, §17. Whatever defects may exist in

the Zegarelli chain of title, it has no where been claimed that

these defects were created by the defendants. It is clear that

there can be no recovery on the covenants contained in the deed.

The issue here is rescission. It is not clear upon what

grounds plaintiff seeks this remedy. Even though the traditional

grounds for recission, fraud, misrepresentation, and mutual

mistake, have not been specially pleaded as required by Mass. R.

Civ. P. 9(b) the Court will consider whether the evidence supports

any of these grounds. The relevant facts on these points are as

follows:

By deed dated December 4, 1972 and recorded in Book 3843,

page 476 third party defendant Marguerite M. Hooley conveyed a

number of lots in Standish Gardens, including locus, to the

defendants. (Exhibit No. 7) Third party defendant Attorney Oates

represented both parties in this transaction. (Tr. 166)

Attorney Oates knew that no taxes had been paid on the land

conveyed. (Tr. 96). Attorney Oates did not request from the

town of Plymouth a certificate of municipal liens previous to

the sale although it is a usual practice to so do (Tr. 100)

because he understood he would have had to obtain one for each

of the 200 odd parcels sold. (Tr. 101). Attorney Oates, who is

a Land Court examiner, was familiar with the title and informed

the defendant he had checked it and that is was a good record and

marketable title. (Tr. 165).

After the Hooley to Zegarelli deed was recorded, the defendants

Zegarelli received a letter dated April 30, 1973 from the Town of

Plymouth Assessors' Office stating that the assessors' records

showed the lots were never owned by Miss Hooley and that therefore

the defendants could not be assessed as owners. (Exhibit No. 4).

The defendants gave this letter to Attorney Oates who wrote a

letter dated May 4, 1973 to the Board of Assessors stating in

material part:

"I realize that there may be some question of the

validity of the base deed in the late 1800's by an

Indian princess of these so-called "Indian Lands."

Nevertheless, the record title for over fifty years

shows that Miss Hooley had and conveyed good title."

(Exhibit No. 10)

In October 1973, the defendants asked Attorney Goldberg to

check their title. (Tr. 103-104). Attorney Goldberg hired a title

examiner and received a report from him. Thereafter Attorney

Goldberg went to the Plymouth Assessors' Office and was informed

taxes were not assessed on Standish Gardens because it was

considered low value land. He was not informed who the assessed

owner was. (Tr. 106) He rechecked the title back to 1916 and

informed the defendant his title was good. Thereafter, in 1975

the defendants sold locus, a portion of the land conveyed to them

by Miss Hooley, to the plaintiff. Attorney Goldberg represented

the defendants in this transaction, drafted the deed, and sent

a bill for drafting to the plaintiff. (Tr. 107). The plaintiff

was not represented by an attorney in this transaction.

Attorney Goldberg became aware that locus was assessed to

Hammond as a result of a subsequent title examination by Ms. Prue.

(Tr. 107). This examination occurred after the defendants sold

locus to plaintiff.

The above facts do not support a finding of fraud, misrepresentation

or mutual mistake. Whatever statements the defendants

made to the plaintiff concerning the defendants' ownership of the

land, there is no evidence these statements were made in bad faith.

The defendants had been informed that according to the Plymouth

assessor's records they did not have title. They immediately went

to their attorney, who, after searching the records, assured them

that they in fact did have good title. They did not disclose

the assessor's report to the plaintiff, nor were they under any

duty so to do. By the same token they in no way deceived the

plaintiff as there was no evidence of any inquiry being made or

conversation being held with the plaintiff as to this. At most

there was non-disclosure, certainly no misrepresentation. As a result, there can be no recovery on the basis of

fraud, misrepresentation or mutual mistake. Yaghsizian v.

Saliba, 338 Mass. 794 (1959); Swinton v. Whitinsvi1le Savings

Bank, 311 Mass. 677 (1942). See also Pybus v. Grasso, 317 Mass. 716 , 720-21 (1945).

Thus, the Court concludes the plaintiff is not entitled to

relief and orders the plaintiff's complaint dismissed.

As the defendants seek judgment against the third party

defendants for all sums that may be adjudged against the defendants

in favor of the plaintiff and as the Court has concluded the

plaintiff is not entitled to recovery from the defendants, it is

unnecessary to consider the allegations of the third party complaint.

The plaintiff has submitted three requests for rulings. All

of these concern the status of the Zegarelli chain of title, that

is, whether the title was good, clear and marketable. As this

determination is irrelevant to the present action, the plaintiff's

request for rulings are not granted.

Judgment accordingly.

CARLO BORTONE vs. LOUIS ZEGARELLI, ANGELA ZEGARELLI vs. LAWRENCE DILORENZO, JAMES M. OATES, JR., MARGUERITE M. HOOLEY

CARLO BORTONE vs. LOUIS ZEGARELLI, ANGELA ZEGARELLI vs. LAWRENCE DILORENZO, JAMES M. OATES, JR., MARGUERITE M. HOOLEY