On March, 29, 1974 the petitioner, G. Douglas Hofe, Jr., and

Skymeadow Airfield, Incorporated, filed a petition with this Court

to confirm title to a large parcel of land situated in Orleans in

the County of Barnstable and shown on the plan filed with said

petition. Subsequently, motions to amend the petition by eliminating

the corporation as a party and to sever and dismiss a portion

of the land shown on the filed plan were filed and allowed by this

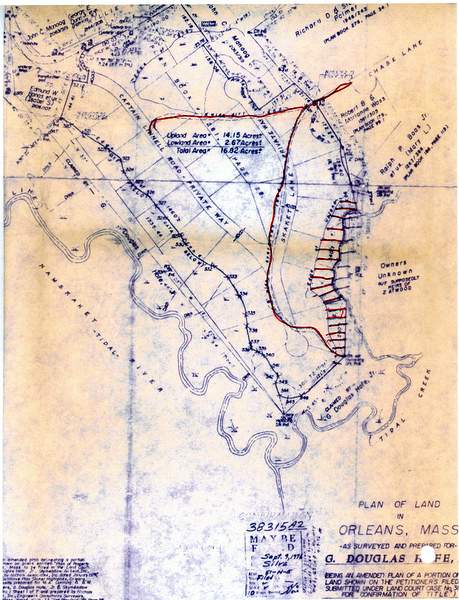

Court. An amended plan dated July 27, 1976 entitled "Plan of Land

in Orleans, Mass. as Surveyed and Prepared for G. Douglas Hofe,

Jr.," by Schofield Brothers, Inc., Was filed on September 9, 1976

as Plan No. 38315A2. This plan shows the land remaining in the

case after the severance (the "locus"); adjoining the southwesterly

and southeasterly boundaries thereof is other property denoted by

the surveyor as "claimed by G. Douglas Hofe, Jr." It is also claimed

by the heirs of Julia Atwood and the decree plan will so indicate.

The petitioner apparently sought by the severance to eliminate any

objection to his title, but he was unsuccessful in this objective.

There still are two contested matters involved in the present proceeding.

One is as to the title to that portion of the locus shown

on the A2 plan as lying between the edge of upland and the southeasterly

boundary of the land claimed by the petitioner, being in part the

center line of a tidal creek. The area in question is cross-hatched

on a reduced copy of the A2 plan attached hereto as Appendix A. A

copy thereof was introduced at the trial as petitioner's Exhibit No. 2.

The other is as to the existence of rights to use the dirt roads shown

on the A2 plan (the "Plan"). The Plan, in accordance with Land Court

rule, shows that on the ground there are two 8-foot wide dirt roads

leading to the locus from land of Robert B. and Marianne Wass. The

most northerly of such roads terminates at a private way known as

"Captain Linnell Road," but the other 8-foot wide road, characterized

as "overgrown" by the surveyor, leads to the area in dispute.

Answers were filed on behalf of Wilhelmina Bearse, Administratrix,

David G. Bearse, Madeline P. Armeson and Marion L. Kendrick

in which such defendants claim to own a portion of the same land

claimed by the petitioner, but made no specific claim of any right

of way across the locus. The other defendants, Norma B. Santiago,

Dorrance M. Bearse, Alvah T. Bearse and Gloria Julianna Jablonski,

answered denying the title of the petitioner to the land shown on

the filed plan and claimed to own a portion thereof. During the

course of the proceeding, the attorney for the latter respondents

withdrew from the case, and they proceeded thereafter to represent

themselves.

A trial was held at the Land Court on January 4, 1979 at which

a stenographer was appointed to record the testimony. All exhibits

introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose

of any appeal. The petitioner based his case both on record title

to the premises and to title by adverse possession. As to the area

in question, the examiner reported that a predecessor in title,

William F. Mayo, had acquired title to seven parcels of land from

Asaph Mayo by deed dated January 26, 1852 and recorded with

Barnstable Deeds in Book 54, Page 380 (Abstract, sheet 54). Of

the seven parcels conveyed by said deed, the examiner placed three

of these in the neighborhood of locus; of such three, parcels 5 and

6 allegedly comprise a portion of the land heretofore severed. The

remaining parcel number 2 in the deed was described as follows in

the 1852 conveyance: "A lot of land situated in said Orleans called

the Sandy Bank field, containing about 11 acres and bounded on the

North by land of Alfred Kendrick and Northeasterly by land of

David Taylor and others, on the Southeast by the meadow and south-

west by the meadow." The difficulty with the record title of this

parcel is found in the deed out from William F. Mayo to T. Frank

Ellis dated July 9, 1914 and recorded with said Deeds in Book 332,

Page 272 (Abstract, sheet 55). The description in the 1914 deed,

as abstracted by the Land Court examiner, read: "All my right,

title, and interest in a certain piece of swamp and upland situated

in the northwest part of said Orleans at a place called Sandy Bank.

Containing about 3 Acres. For title see 2nd parcel of land sold

to me by my father, Asoph (sic) Mayo in Book 54 Page 380, dated

January 26, 1852. Recorded at Barnstable Registry of Deeds." The

description thereafter in the chain of title followed that in the

Mayo to Ellis deed of 1914. Title to a small part of locus derives

from another chain, but it is apparent that much more than three

acres stems from the Mayo conveyance. The petitioner has argued

that it was intended in the 1914 grant to convey all of the second

parcel in the 1852 deed. The argument is two-pronged. On the one

hand, the inventory in the estate of William Mayo was introduced

as an exhibit (Petitioner's Exhibit No. 8), and shows that the

decedent died without owning real estate, the argument being therefore

that it was his intention to convey all the second parcel to

Mr. Ellis. The petitioner also relies upon cases such as Waller

v. Barber, 110 Mass. 44 (1872) and Ide v. Bowden, 342 Mass. 22

(1961), which hold that under certain circumstances the wording

of a title reference may be employed to interpret the grant and

ascertain the intention of the parties if the description is

ambiguous. I have no difficulty in applying this rule to the

present case and in ruling that the petitioner has shown good title

to the premises shown on the A2 plan other than to the area in

dispute. But an argument based on the inclusion of the second

parcel as described in 1852 in the deed to one of the petitioner's

predecessors in title does little to solve the problem with which

the Court is presented. The Mayo to Mayo deed bounds both south-

easterly and southwesterly by "meadow." The term "meadow" as used

in conveyancing apparently has not been defined as yet by the

Supreme Judicial Court, but it is understood by conveyancers as

meaning "low-lying grass land subject to natural flooding." On

Cape Cod it is said that the favorite son was usually the devisee

of the salt marsh which was grass land flooded with tides. The

hay that grew was encrusted with salt and could be used to feed

the livestock; it was a source for providing them with sufficient

salt without purchasing the latter. It appears that upland and

meadow were used to distinguish two different types of land with

the latter being subject to inundation. In the present case, a

description which bounds by the meadow would not include as part

of the premises conveyed the land to the southeast of the "edge of

upland" as shown on the A2 plan. I therefore find and rule that

the petitioner has not sustained his burden in showing record title

to the area in dispute. However, the petitioner claims to have

acquired title to the disputed area by adverse possession.

At the trial the petitioner relied on the following acts of

dominion to establish his claim to the disputed area. Title was

taken to the parcel in question in 1956 by deed from Elijah C. Long

dated June 4, 1956 and duly recorded in said Deeds, Book 958, Page 5

(Abstract, sheet 61). Thereafter real estate taxes were paid by

the petitioner (Petitioner's Exhibits No. 10, 11, 12A, 12B, 12C

and 12D). At approximately this time the petitioner filed with

the Orleans assessors a plan by Schofield Brothers, Inc. dated

July, 1956 which includes the area in dispute as a portion of the

petitioner'S land (Petitioner's Exbibit No. 10). Advertisements

for sale of 45 acres of upland, 40 acres of protective salt

marsh, and an adjoining subdivision with 20 lots were placed in

the Boston Herald on May 3rd and 10th, 1964 and the Wall Street

Journal on May 1st of that year. A lilac bush was transplanted to

the petitioner's home from the locus. A letter was written to Mr.

Harold Moye, a prominent Cape Cod developer, by the petitioner in

February of 1965 in which it was suggested by the petitioner that

the addressee might be interested in the land in question; the

letter specifically referred to "and extensive bordering salt marsh

extending to Namskaket Creek;" negotiations also have been had with

others relative to the sale of locus. The petitioner's Exhibit

No. 17 is an elaborate presentation to the appropriate Orleans town

officials of a proposed subdivision encompassing locus including

the disputed area made on behalf of Michael A. Dunning and Brian M.

Kelley, with whom petitioner had executed a purchase and sale agree-

ment. The first set of the definitive plans of Skaket Highlands,

the subdivision in question, is petitioner's Exhibit No. 16 in this

proceeding and includes the disputed area. The petitioner also has

been shown as an adjoining owner on plans of the property of abutters.

This is so in the case of an April, 1964 plan by Arthur L. Sparrow Co.

(Petitioner's Exhibit No. 6) and of July, 1973 plan of land of Arlene

W. Rowe by Schofield Brothers (Petitioner's Exhibit No. 7). Tests

have also been conducted on the locus, but not clearly on the disputed

area for percolation and for the height of the land above

the water table to be presented to the planning board.

It is apparent that whatever title the petitioner may have

acquired by adverse possession did not fully ripen until after the

filing of the present proceeding in this Court, for record title

was taken in 1956, no evidence of adverse use by a predecessor in

title to whose occupancy that of the petitioner might be tacked

has been shown, and the petition was filed in 1974 although the

case was not heard until this year. The case law is to the effect

that the filing of the petition stops the running of prescriptive

rights in favor of third parties, but there seems to be no reason

why the time which elapses during the pendency of a registration

or confirmation case cannot be considered in computing the necessary

years for acquisition of title by adverse possession. Nonetheless,

I find and hold that even though the time span has been shown, the

petitioner has not borne the burden of establishing title by adverse

possession to the disputed area. The doctrine of Dow v. Dow, 243 Mass. 587 (1923), does not help him. The rule in the Dow case is to

the effect "that where a person enters upon a parcel of land under

a color of title and actually occupies a part of the premises

described in the deed, his possession is not considered as limited

to that part so actually occupied but gives him constructive

possession of the entire parcel. The entry is deemed to be coextensive

with the grant upon the ground that it is the intention

of the grantee to assert such possession." Citations omitted.

In the present case I have ruled that the grant did not include

the meadow of which the disputed area forms a part and that there-

fore Dow does not apply. The difficulty with the petitioner's case

is that there has been no showing of any open and notorious

activities which took place and which would have been likely to

direct the attention of the respondents to an adverse use of the

land they claimed. Historically, it has been difficult to obtain

title by adverse possession in Massachusetts if the premises in

question are "wild land." See Cowden v. Cutting, 339 Mass. 164

(1959). In every case it must be shown that the use of the premises

has been open, continuous, exclusive and adverse under a claim of

right for at least twenty years. Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 ,

252 (1964); Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949). It is

well established that the degree of proof necessary to prove title

by adverse possession runs with the character of the property, the

purpose for which it is adapted and the uses to which it has been

put. Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961); LaChance v.

First National Bank & Trust Co., 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938).

In Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 (1955), where the court

clarified the tests as to whether use of the property was "open

and notorious," it was said:

"To be open the use must be made without attempted

concealment. To be notorious it must be known to some

who might reasonably be expected to communicate their

knowledge to the owner if he maintained a reasonable

degree of supervision over his premises. It is not

necessary that the use be actually known to the owner

for it to meet the test of being notorious."

I have no difficulty with the concept that activities of an

intellectual nature carried on off the property may constitute

elements of a claim of adverse possession such as correspondence

with town officials, submission of plan including the property to

the planning board and payment of taxes. In addition and adequately

to meet the requirements of adverse possession, there must also be

physical contacts with the disputed area. There has been no proof

of such physical activity on the ground in the present proceeding.

The only such activity would seem to be for the limited tests of

the nature of the soil to which the petitiouer testified. Accord-

ingly, I find and rule that the petitioner has not borne the burden

which is his of proving that he has acquired title by adverse

possession to the disputed area.

The remaining contest concerns rights in the more southerly

way shown on the A2 plan. Neither party offered any explanation

as to the use made of the 8-foot way over the years. In Merry v.

Priest, 276 Mass. 592 (1931), the Supreme Judicial Court inferred

that the burden of proving the title sought to be registered was

free from encumbrances rested on the petitioner but that the extent

of the encumbrances was an affirmative fact to be proved by those

who claimed its benefit. The respondents in the present case

presented no evidence by which the Court could find that they had

either a prescriptive or record right to use the 8-foot wide over-

grown road. For all that appears on the present state of record

the road may have been used randomly by members of the public

without any claim of right. Reference in the title to other

portions of the land formerly owned by the petitioner to a right

of way to reach the cranberry bog do not suggest that any way or

bog was located at the southeasterly corner. Since it does not

appear that any third party has shown such right, title registered

free from any rights in the roads or ways shown on the Plan. On

all the evidence I find and rule that the petitioner has borne the

burden of establishing title to the land shown on the A2 plan

other than the disputed area and that a decree may be entered

confirming as of 10:00 A.M. on May 25, 1978 the petitioner's

title to said land subject to the filing with the Court of the

additional material heretofore requested and to such matters as

are revealed by the abstract and are not in issue, but free from

any rights in the above mentioned ways.

Decree accordingly.

G. DOUGLAS HOFE, JR., v. WILHELMINA BEARSE, ADMINISTRATRIX, DAVID G. BEARSE, MADELINE P. ARMESON, MARION L. KENDRICK, NORMA B. SANTIAGO, DORRANCE M. BEARSE, ALVAH T. BEARSE and GLORIA JULIANNA JABLONSKI.

G. DOUGLAS HOFE, JR., v. WILHELMINA BEARSE, ADMINISTRATRIX, DAVID G. BEARSE, MADELINE P. ARMESON, MARION L. KENDRICK, NORMA B. SANTIAGO, DORRANCE M. BEARSE, ALVAH T. BEARSE and GLORIA JULIANNA JABLONSKI.