ARTHUR G. ROGERS and FLORENCE M. ROGERS vs. KATHERINE F. FINNERTY.

ARTHUR G. ROGERS and FLORENCE M. ROGERS vs. KATHERINE F. FINNERTY.

REG 39581-S

January 8, 1980

Essex, ss.

Sullivan, J.

ARTHUR G. ROGERS and FLORENCE M. ROGERS vs. KATHERINE F. FINNERTY.

ARTHUR G. ROGERS and FLORENCE M. ROGERS vs. KATHERINE F. FINNERTY.

Sullivan, J.

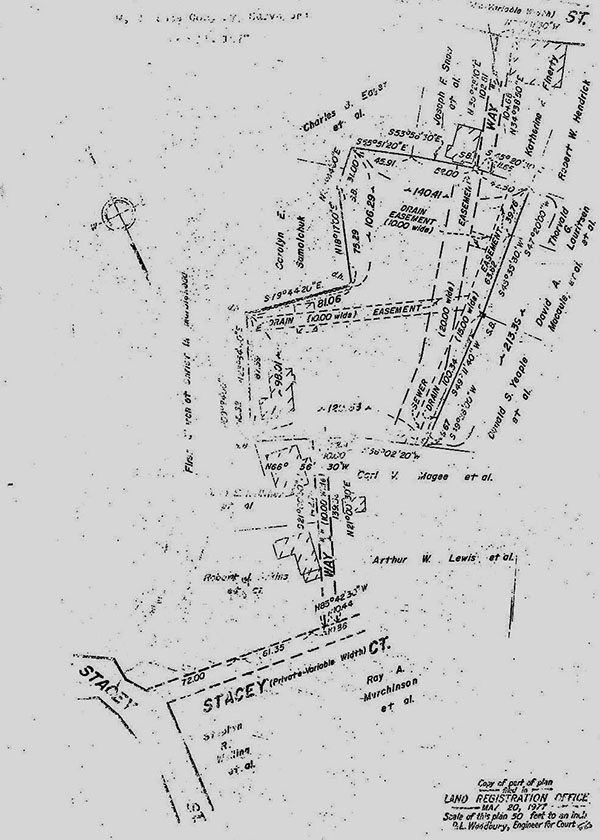

The plaintiffs are the registered owners named in and present holders of Certificate of Title No. 47727 issued by the Essex South Registry District of the Land Court (Exhibit No. 2). Said certificate covers land in Marblehead in the County of Essex situated between Selman Street to the northeast and Stacey Street to the southwest and without frontage on either; this registered land is shown on Land Court Plan No. 39581A (Exhibit No. 1), a copy of which is attached hereto. There is appurtenant to it as found by this Court in Registration Case No. 39581 and set forth in said Certificate of Title a right of way to Stacey Court with which we are not concerned in this present proceeding and also "the right to use Way '2', as shown on said plan, to and from said land and Selman Street, in common with all other persons lawfully entitled thereto." Way "2" passes from Selman Street by the defendant's house and through her backyard to the plaintiffs' land, all as shown on Exhibit No. 1. The plaintiffs complain that the level of Way "2" at the southwesterly end of the brick paving thereof is obstructed by rocks and that the paving itself has raised the grade of said way about one foot; that the way is obstructed frequently by the parking of the defendant's car; and that the defendant maintains a garden within the way.

A trial was held at the Land Court on June 27, 1979 at which a stenographer was present to record the testimony. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows: the land over which Way "2" passes is owned in fee by the defendant; said land of the defendant formerly was about thirty inches lower than the grade of Selman Street which was reached by steps consisting of two large stones; when the defendant's husband retired from the service and the couple returned to live permanently at the defendant's house, Mr. Finnerty paved the driveway with bricks to eliminate the drop down from the street line to the defendant's property; the paving of the driveway extends for approximately sixty feet from the sidewalk; this is short of the terminus of paper Way "2" at the plaintiffs' land; there is a substantial area of the defendant's backyard, about forty feet, over which Way "2" continues to reach the plaintiffs' land; at the end of the paved way the defendant's husband put in a 2 by 8 board to hold the stones and sand together with some bricks and large stones; flooding on the land of the plaintiffs has extended onto the land of the defendant, caused erosion and made the obstruction necessary; the defendant's car is approxi mately six feet wide so there is room to walk by it on Way "2" when it is parked therein but not to drive by it; since Way "2" appears to run parallel to the defendant' s northwesterly line and to be bounded thereby a garden maintained by the defendant is situated therein adjacent to the boundary line; the garden encroaches into the way approximately one foot to eighteen inches; the plaintiffs are elderly and would have difficulty in traversing the way to step over the obstruction at the end of the paving, but they also might well have a difficulty in walking over that part of Way "2" which is in its natural state.

It is settled that the dominant owner, the plaintiffs, may make reasonable repairs and improvements to the way if they so elect, Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 173 (1948), and that the servient owner has no duty to repair. Archambault v. Williams, 359 Mass. 742 (1971). If the latter should elect to do so, however, such repairs cannot be of such a nature as to result in a change in grade which will "make the way less convenient to any appreciable extent ." Vinton v. Greene, 158 Mass. 426 , 433 (1893). It also cannot be doubted that the plaintiffs have the right to use the entire ten feet in width of the way for passage to and from their registered land. This is not to say, however, that the defendant as owner of the fee may not use it for all purposes not inconsistent with the plaintiffs' rights. New York Central Railroad v. Ayer, 242 Mass. 69 , 75 (1922). This has been held to include the right to park, either temporarily as in Tehan v. Security National Bank, 340 Mass. 176 (1959) or on a more permanent basis as in Brassard v. Flynn, 352 Mass. 185 (1967) so long as there is no interference with the rights of the dominant owner. Finally, no obstructions may be placed in the way by the servient owner.

If these legal principles are applied to the facts which I have found, it seems apparent that the defendant may not maintain a garden within the limits of Way "2" as shown on Exhibit No. 2, that the boulders which have been placed at the end of the brick paving and appear clearly on Exhibit No. 6 must be removed; that the increase in grade between the brick surface and the lawn is insufficient to require its elimination although the plaintiffs are free, if they so elect and at their expense, to install a surface from its present termination to the property line; that to the extent the difference in grade of the end of the driveway from that from the backyard is a result of the improvements made by the defendant's husband at the street line the plaintiffs benefit by such improvements and cannot be heard to complain; that until the backyard portion of the way has been made passable for motor vehicles, the defendant may continue to park one car in Way "2" so long as there is available to the plaintiffs for foot passage a portion thereof at least four feet in width; and that at such time as Way "2" becomes suitable for vehicular traffic to the plaintiffs' premises, the parking by the defendant, her successors and assigns in the way is to cease other than for temporary stops to disembark passengers and to bring bundles into the house, and

I so rule.

Judgment accordingly.

exhibit 1