The plaintiff, Town of Arlington (the "Town"), a municipal corporation located in the County of Middlesex, brings this complaint in which it seeks a determination that the restrictions set forth on Certificate of Title No. 18783 are no longer enforceable by virtue of the provisions of G. L. c. 184 §28. [Note 1] Named as defendants are the original grantors who conveyed the land covered

by said certificate to the Town, their heirs and devises, and the Attorney General of The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The only answer was by the Attorney General who alleged that the restriction in question constituted a trust limiting the use of the town's property to the purposes mentioned in the deed to it.

There being no dispute as to the applicable facts, the case was submitted to the Court on oral arguments made on January 20, 1981 and on briefs filed by the Town and the Commonwealth. On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

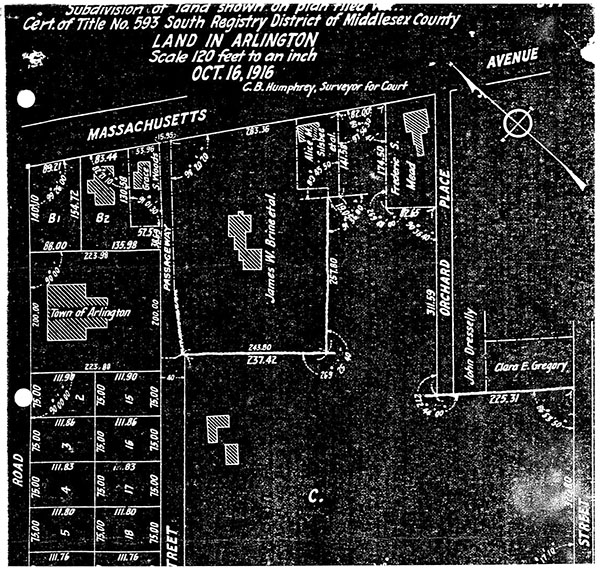

1. The Town is the registered owner named in and holder of Certificate of Title No. 18783 issued by the Middlesex South Registry District of the Land Court covering Lots 2, 3, 15 and 16 on Land Court Subdivision Plan No. 547-C, a copy of which is attached hereto and marked Appendix "A".

2. Said certificate includes the following paragraph:

The above described land is also subject to an agreement to impose restrictions thereon contained in deed given to Florence W. Bailey, dated October 2, 1906 and being Document No. 2874, so far as in force and applicable; and to the further restriction that the above described land shall be used only as a playground for the children residing in the Cutter School district, under the direction and control of and in accordance with any rules and regulations made by the School Committee of said Arlington or its successors.

3. The Cutter School referred to in the restriction is located on land marked "Town of Arlington" on said plan. The four lots referred to in the restriction adjoin the school property and have been used as a playground as provided therein.

4. The restriction was imposed by a deed from Clara S. Pierce and Peter Schwamb to the Town of Arlington dated January 29, 1925 and registered as Document No. 57097 in which deed there was a statement to the effect that "said land is donated in memory of Theodore Schwamb, late of said Arlington." Mr. Schwamb was the petitioner in the original registration proceedings in Case No. 547, is said to be the father of the grantors in said deed and was a prominent citizen of Arlington.

5. Document No. 2874 referred to in the outstanding certificate of title was a deed from said Theodore Schwamb to Florence W. Bailey and contained an agreement to impose certain residential restrictions on all the lots on said Robbins Road southwest of land of the Town of Arlington. Said restrictions apparently have heretofore been modified and now have expired by operation of law. (See footnote one.) Their applicability and enforcement is not in issue here.

6. The school committee of the Town voted on October 9, 1979 to close the Cutter School at the end of the 1980-81 academic year, and on November 27, 1979 declared the school surplus as of

September 1, 1981.

7. It is alleged in the complaint that the Town is currently soliciting requests or proposals for the adaptive re-use of the school building and the land upon which it is situated, perhaps including a portion of the land covered by said certificate of title.

8. The Town construes the provision of the certificate of title as constituting only a restriction which has not been brought forward as provided in G. L. c. 184 §28 and which therefore has expired. [Note 2] The Commonwealth conversely argues that the language in the restriction imposed a public charitable trust on the Town which it accepted and which cannot now be chaged. There the lines of disagreement have been drawn.

There are two lines of cases running through the Massachusetts decisions, one line typified by MacDonald v. The Street Commissioners of Boston, 268 Mass. 288 (1929); Barker v. Barrows, 138 Mass .578, 580 (1885); Brooks v. City of Boston, 334 Mass. 285 (1956); and Loomis v. City of Boston, 331 Mass. 129 (1954). The other line of cases to which the Attorney General argues the present state of facts is similar is typified by Nickols v. Commissioners of Middlesex County, 341 Mass. 13 (1960); Salem v. Attorney General, 344 Mass. 626 (1962); and Dunfey v. Commonwealth, 368 Mass. 376 (1975). In the Opinion of the Justices, 369 Mass. 979 (1975) there are examples of both types of conveyances and in Newburyport Redevelopment Authority v. Commonwealth, Mass. App. Ct. (1980) [Note 3] the Appeals Court considered a myriad of grants and other instruments relating to a parcel of land on Newburyport Harbor, and did find a public trust as to a portion thereof.

I have carefully reviewed the language of the deeds or other instruments involved in the above cases and in several additional decisions where the existence of a trust was in issue, and I have concluded that the language used in the present case is a restriction which has now expired rather than a trust which the Town is bound to continue to administer. I have been led to this result by the following considerations. There is the absence of any use of the word "forever" on which Justice Grant placed significance in the Newburyport case. Even though said section 28 was not adopted until after the gift made to the Town so it is arguable that the donors did not anticipate the fifty year limitation, it historically has been the practice to include words such as "always" or "forever" where it was intended to impress the conveyance with a trust. There is no such intimation here. While use of the word "restriction" is not necessarily determinative since the court must look to the substance of the words employed, it is significant in the

present case as it is obvious that the original donors (or their advisers) were knowledgeable as to estates in real estate. They must have realized that use of the word "restriction" imposed a limitation upon the purposes to which the land subject thereto can be put but did not commonly establish a trust. If the donors had intended the latter result, then they easily could have said so. Indeed the provision that the gift was made in memory of the original developer of the area imports a wish that some municipal purpose be served by the Town's use of the property to honor their father, but not necessarily the same use as was originally set forth in the deed. There is nothing to show that a playground was dear to the Schwamb heart, other than a logical use for land

next to a school. It may well have been that the restricted lots were among the last remaining in the tract and that the decision was made by public spirited citizens to give them to the Town rather than selling them for profit. As the court said in the MacDonald case:

There are no words to the effect that the conveyance is upon a perpetual trust. If a trust had been intended, words indicative of that design reasonably might be expected in a conveyance affecting valuable real estate in Boston so recently as 1879. While no particular words are necessary to the creation of a trust, some words in connection with attendant factors must point to a trust or none is established. (295)

The same court further in said decision stated:

This appears to be the intent of the parties to that deed, to give effect to which is the cardinal rule in the interpretation of such instruments. That purpose has been effectuated by the laying out of the public street in 1880 and the maintenance of it through the years that have passed since that time. The principle underlying cases like Rawson v. Uxbridge, 7 Allen 125 , and Barker v. Barrows, 138 Mass. 578 , tends strongly to support the conclusion that no trust was here created. The case at bar thus is quite distinguishable from Cary Library v. Bliss, 151 Mass. 364 ... (further citations omitted) ... and similar decisions where the words of the deed and the circumstances of the gift indicated a purpose to create a trust.

The same is true here. The purpose for which the gift was made has been fulfilled and the intent of the grantors fulfilled. There is nothing, either in the words of the deed or the attendant circumstances, to suggest that a trust was intended.

I therefore find and rule that the language set forth in Certificate of Title No. 18783 relative to the playground imposed only a restriction and not a trust; that said restriction was imposed in 1925; that more than fifty years have elapsed since its imposition; that no notice of restriction was recorded before the expiration of the fifty years for which provision is made in

G. L. c. 184 §28; that the Town of Arlington holds title to said Lots 2, 3, 15 and 16 free from any restrictions thereon; that no trust has been established for the benefit of the school children living in the Cutter School district of which the Town is trustee; and that said land may be disposed of in accordance with the other provisions of law.

Judgment accordingly.

TOWN OF ARLINGTON vs. CLARA S. PIERCE, her heirs and devisees, PETER SCHWAMB, his heirs and devisees, PETER E. SCHWAMB, LOUISE SCHWAMB, NORMAN P. HILL, W. THEODORE PIERCE, RICHARD B. HILL, ATTORNEY GENERAL of The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, BARBARA S. PORTER and HELEN W. SCHWAMB.

TOWN OF ARLINGTON vs. CLARA S. PIERCE, her heirs and devisees, PETER SCHWAMB, his heirs and devisees, PETER E. SCHWAMB, LOUISE SCHWAMB, NORMAN P. HILL, W. THEODORE PIERCE, RICHARD B. HILL, ATTORNEY GENERAL of The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, BARBARA S. PORTER and HELEN W. SCHWAMB.