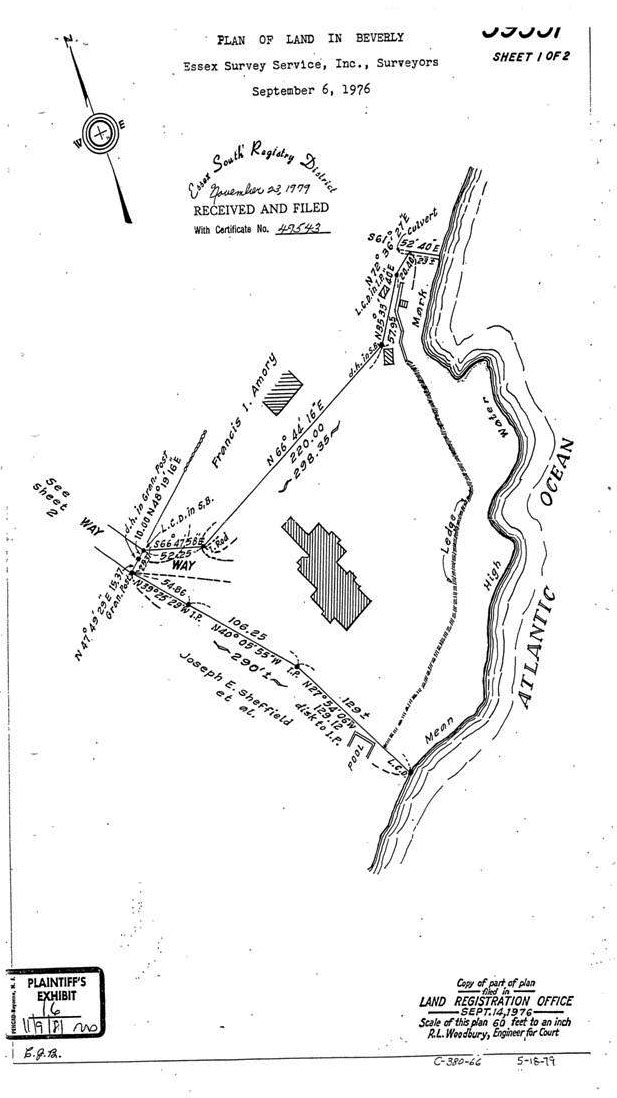

Pursuant to a decree of this Court dated November 6, 1979, the Essex South Registry District of the Land Court issued to Donald E. Besser and Juliet Besser, of Beverly in the County of Essex, husband and wife, as tenants by the entirety, Certificate of Title No. 49543 (Exhibit No. 1) in which they were named as the registered owners of the land described therein. Reference is made in said Certificate of Title to a plan drawn by Essex Survey Service, Inc., dated September 6, 1976, as modified and approved by the Court. A copy of the decree plan (Exhibit No. 16) is attached hereto as Appendix "A". In August of 1980, the defendants, Douglas M. Moody and Emily A. Moody, also of Beverly, acquired title from Elizabeth M. Sheffield by deed dated August 1, 1980 and recorded with Essex South District Deeds, Book 6723, Page 002 (Exhibit No. 14) to a parcel of land, with the buildings thereon, situated off Prince Street, and adjoining the Besser premises on the southwest.

In the spring of 1981, the defendants acting through a contractor commenced the repair and restoration of an existing sea wall to end, or at least impede, the undermining by the Atlantic Ocean of a corner of the Moody swimming pool. The placement of the retaining wall in relation to the common property line led to the initial dispute between the parties. It was followed by a disagreement as to a deck, railings and fence about the pool. Finally, on July 8, 1981, the complaint was filed in the present proceeding in which the plaintiffs asked the Court to rule that their boundaries were as shown on the decree plan and to order the defendants to remove that portion of the retaining wall which encroached on the Besser land. Subsequently, the complaint was amended, and a temporary restraining order and later a preliminary injunction were entered restraining certain specified activities on the land described in said Certificate of Title No. 49543. The defendants answered that they had been without knowledge of the registration proceedings, that their survey showed the boundary line located further to the east, that they acted in good faith, that the only encroachment is 4.31 feet of the retaining wall which they stand ready to remove and by amendment and counterclaim that the plaintiffs consented to the placement of the retaining wall.

At the pre-trial conference, the defendants' attorney disclaimed specifically any question of fraud in the registration decree. Kozdras v. Land/Vest Properties, Inc., Mass. (1980) [Note 1]. It was agreed that the two principal issues in the case were whether any encroachments for which the defendants were responsible existed, and if so, to what extent. Questions which surfaced in the stormy summer of 1981 relative to the zoning ordinance and its possible violation play no part in the present proceeding.

A trial was held at the Land Court on November 9 and 20 and December 8, 1981 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and report the testimony. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein by reference for the purpose of any appeal.

On all the evidence, I find and rule as follows:

1. The filed plan in Registration Case No. 39351 (Exhibit No. 2) contained an error of transcription in which the bearing on the line here in question appears as N.27° 54' 06" W, rather than N.26° 54' 06" W, which is correct. This mistake was perpetuated on the decree plan so the property lines did not close if the original bearing was held. [Note 2]

2. The filed plan shows offsets to the apron of the Moody swimming pool so the disputed common boundary line can be recaptured using the iron pipe shown on the decree plan and the two offsets. The Land Court disc at the southeasterly end of the line now has disappeared (presumably a victim of the Ocean's action) but a drill hole in lead remains which marks the former location of the Land Court disc.

3. The defendants in purchasing the Sheffield property after the completion of the registration proceedings understood the property line to be further to the northeast. However, Mrs. Sheffield had received notice of the registration proceedings and filed no objection. At the most, there may have been, if litigated, an honest disagreement as to the location of the line, but the registration decree is now final, and the defendants do not attack it. See General Laws, c. 185, §45.

4. On May 21 of last year, wooden forms were placed on the Moody land preparatory to the pouring of the concrete for the retaining wall and its footing. On the previous May 12, drilling began for the two inch holes in the ledge to be pinned with inch and one-half steel rods rising in a vertical direction and then strung horizontally with other re-enforcing rods.

5. The Bessers testified that they were unaware of the drilling and did not realize that the retaining wall was being constructed until late in the afternoon of May 21 when they saw the forms. A meeting was scheduled for the following morning to discuss the matter. The Bessers testified that they told the Moodys, their contractor, and subsequently the subcontractor, that the proposed retaining wall encroached on the Besser land. They also expressed displeasure with the height and proposed appearance of the wall. The subcontractor proposed cutting back the wall, and dropping it down to preserve the view. The point at which it drops down is about .7 of a foot on the Bessers' side of the line (Exhibit No. 5). The Bessers' testimony is to the effect that on May 22 they told the Moodys of their objections, that the Moodys insisted on going forward and that the Bessers then said, "If you are going to pour the wall anyway, at least cut it down in height." The Moodys understood the Bessers to be complaining only of the height of the wall and that the Bessers were content for the project to continue if the wall were dropped down. The plaintiffs' version of the events of May 22 appear to more nearly reflect the actual occurrences of that date, and the Court so finds. However, it also is clear to the Court that the defendants did not believe the wall encroached and agreed to pay the additional expense of lowering the height of a portion of it in a neighborly gesture designed to meet the objections of the plaintiffs.

6. Some preliminary work was done even before the wall was poured in preparation for filling the area between the apron of the pool and the sea wall. Railroad ties were placed to retain the fill. After the wall was in place, the fill was put in the cavity, and Mr. Besser initiated conversations about the deck. The Moodys then delayed going forward with the deck during the period of June 15 to July 2, and their contractor fulfilled other obligations. Finally, a meeting was held at which the parties and their attorneys were present. A suggestion was made by the attorney for the plaintiffs that the deck be catty-cornered at the ocean and near the common line, rather than going out in a straight line to the sea wall, and Mrs. Moody understood the next day that the plaintiffs were agreeable to this. Since that time, a see-through railing has been installed at the edge of the sea wall, plantings have been made and a cedar picket fence installed on the defendants' side of the boundary line which decreases in height as it nears the sea wall (Exhibit No. 20). Photographs of the pool and its appurtenances before and after the improvements of last summer form a part of Exhibit No. 20.

7. The Bessers in actuality were not satisfied, and this litigation is the result.

8. Exhibit No. 5, which was prepared by the plaintiffs' surveyors shows in Detail "B" the encroachment of which the plaintiffscomplain. There is an encroachment of the wall to its full height of 0.7 feet, and encroachment of 5 feet of the wall as lowered and an encroachment of 7.7 feet of the concrete footing. Exhibit No. 8 and Chalk B prepared by the defendants' surveyors are in substantial agreement as to the encroachment of the wall, but they do not show the footings or the extent they extend over the line of the registered land. A study of the photographs in evidence confirms the fact that the footings also encroach and do so to the extent of about 2.5 feet beyond the wall. The plaintiffs' exhibit and the defendants' chalk are at slight variance as to the railroad ties which contain the fill, but any encroachment by them seems insignificant.

The rule in Massachusetts in cases of encroachment is well settled. It is stated in Peters v. Archambault, 361 Mass. 91 (1972) at page 92 as follows:

"In Massachusetts a landowner is ordinarily entitled to mandatory equitable relief to compel removal of a structure significantly encroaching on his land, even though the encroachment was unintentional or negligent and the cost of removal is substantial in comparison to any injury suffered by the owner of the lot upon which the encroachment has taken place." (Citations omitted)

The basic reason for the rule, said my mentor, Justice Henry T. Lummus, in the landmark case of Geragosian v. Union Realty Co., 289 Mass. 104 , 108-109 (1935) quoting in turn Knowlton, J. in Lynch v. Union Institution for Savings, 159 Mass. 306 , 308, is rooted in the same doctrine which enforces specific performance of an agreement to purchase real estate.

"Leaving an aggrieved landowner to remove a trespassing structure at his own expense and risk, would amount in practice to a denial of all remedy, except damages, in most cases. If the landowner should attempt to right his own wrongs, a breach of the peace would be likely to result.

The facts that the aggrieved owner suffers little or no damage from the trespass (Harrington v. McCarthy, 169 Mass. 492 , 494; Szathmary v. Boston & Albany Railroad, 214 Mass. 42 , 45; Congregation Beth Israel v. Heller, 231 Mass. 527 , 529; Crosby v. Blomerth, 258 Mass. 221 , 226), that the wrongdoer acted in good faith and would be put to disproportionate expense by removal of the trespassing structures (Kershishian v. Johnson, 210 Mass. 135 , 139; Marcus v. Brody, 254 Mass. 152 , l55; Tyler v. Haverhill, 272 Mass. 313 , 316), and that neighborly conduct as well as business judgment would require acceptance of compensation in money for the land appropriated (Hodgkins v. Farrington, 150 Mass. 19 , 24), are ordinarily no reasons for denying an injuction. Rights in real property cannot ordinarily be taken from the owner at a valuation, except under the power of eminent domain. Only when there is some estoppel or laches on the part of the plaintiff (Nelson v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 270 Mass. 471 , 480, 481;

Malinoski v. D. S. McGrath, Inc., 283 Mass. 1 , 11), or a refusal on his part to consent to acts necessary to the removal or abatement which he demands (Tramonte v. Colarusso, 256 Mass. 299 ), will an injunction ordinarily be refused."

It is true, as the defendants argue, that acquiescense bars a mandatory injunction, see Ferrone v. Rossi , 311 Mass. 591 (1942), but on the facts which I have found the plaintiffs did not acquiesce. They accepted under pressure what they felt to be the lesser of two evils, and the only alternative open to them. The defendants knew that the plaintiffs claimed the wall was extending over the property line, and the law is clear that under these circumstances they proceeded at their own risk, even if the encroachment was unintentional. Tyler v. Haverhill, 272 Mass. 313 (1930). Ordinary prudence would seem to dictate that the plaintiffs accept the sea wall as a benefit to their land in the never ending war with the Atlantic. The neighborly conduct of which Justice Lummus wrote would suggest a similar conclusion. The plaintiffs seem to recognize neither reason. If they so insist, they are entitled to a mandatory injunction to order the defendants to continue the line of the drop in the wall through the footings and to remove the wall and footings to the northeast of the line. The 0.7 encroachment of the upper wall and of the railroad ties is too small in view of the expense, the benefit to the plaintiffs and the difficulty of removal to require removal. In two words it is "de minimis". Harrington v. McCarthy, 169 Mass. 492 , 494-5 (1897).

The plaintiffs also suggest that they are entitled to damages for the defendants' continuing trespass, but the majority of cases in this area of the law award only injunctive relief. See Blood v. Cohen, 330 Mass. 385 (1953). The plaintiffs are to have their mandatory injunction.

No damages or costs are awarded either party.

Judgment accordingly.

DONALD E. BESSER and JULIET BESSER vs. DOUGLAS M. MOODY and EMILY A. MOODY.

DONALD E. BESSER and JULIET BESSER vs. DOUGLAS M. MOODY and EMILY A. MOODY.