TOWN OF GAY HEAD vs. RICHARD E. BROWN.

TOWN OF GAY HEAD vs. RICHARD E. BROWN.

MISC 93025

April 30, 1982

Dukes, ss.

Fenton, J.

TOWN OF GAY HEAD vs. RICHARD E. BROWN.

TOWN OF GAY HEAD vs. RICHARD E. BROWN.

Fenton, J.

This complaint to obtain possession of land and for declaratory judgment was brought under the provisions of G. L. c. 185, c. 237 and c. 231A by plaintiff, Town of Gay Head (the town) against defendant, Richard E. Brown (Brown).

The case involves a 500 square foot parcel of land located on Menemsha Inlet in Gay Head (locus). The town alleges that it acquired title to locus on April 13, 1970 by deed from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; that defendant Brown, has, without right, occupied and claimed ownership to a portion of the locus (lot 2); that the town has demanded that the defendant vacate the land; that the defendant has and continues to refuse to vacate, and that defendant has diminished the value of the town's land by polluting and littering.

Count I of the town's complaint alleges that defendant's actions and claim of ownership constitute a cloud on the title to town land; Count II alleges that defendant is unlawfully trespassing on plaintiff's land, and Count III alleges that the town is entitled to relief in the nature of a writ of entry.

The town asks that the court permanently enjoin defendant from using, possessing and trespassing on the locus and deliver the premises to the town. The town further asks that the court declare it to be the sole owner of the locus and eject defendant therefrom.

In his answer, defendant admits that he has occupied and claimed ownership to the locus, but denies that such occupation and ownership is without right. By way of defense, defendant states that the town's suit is barred both by the statute of limitations and by laches, and that the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

The case came on to be heard and a stenographer was sworn to record the testimony of three witnesses. Thirty-three documents, consisting primarily of plans and sketches of the area surrounding locus, were introduced into evidence. In addition, the court, at the request of the parties, has taken judicial notice of certain papers in Land Court Registration Case No. 7706 (Tilton, 1921) and case No. 16645 (Dyer, 1937). All exhibits in evidence and those documents which the court has judicially noticed are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. [Note 1]

On all the evidence the court finds the following facts:

In 1903 the Commonwealth, acting through the Harbor and Land Commissioners (predecessor to the Division of Waterways), dredged a channel connecting Vineyard Sound and Menemsha Pond on the Gay Head/Chilmark townline. Prior to the dredging in 1903, the existing channel, to the east of the new one, meandered through the tidelands along the Gay Head/Chilmark townline. [Note 2]

The earth dredged in 1903 was thrown to both sides of the new channel, adding to existing land masses and creating new ones.

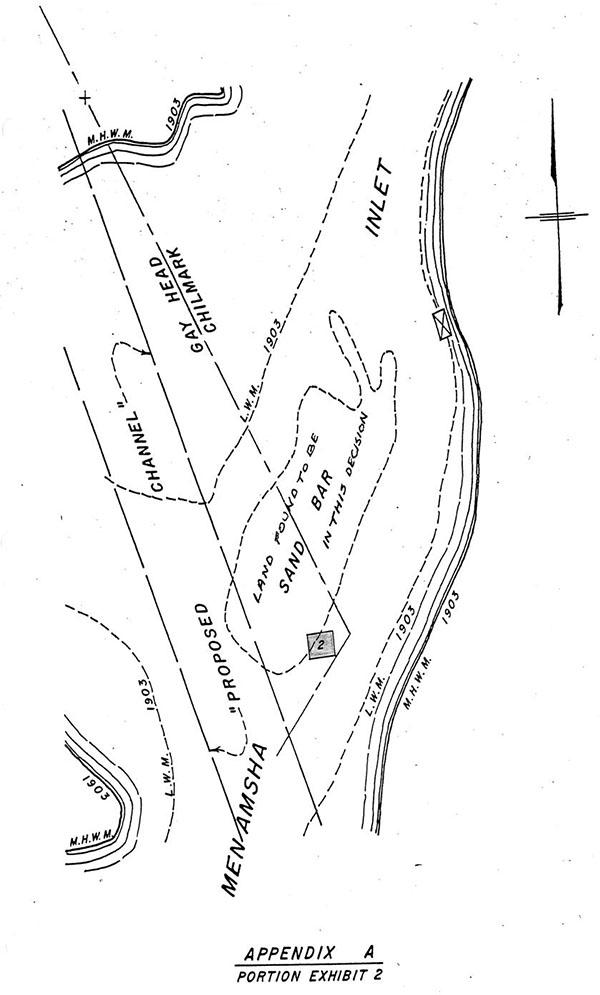

Prior to the dredging there existed a land mass to the east of the proposed channel, a small westerly portion of which was within the area to be dredged. The exact nature of this land mass has been referred to as a ''natural island" by the defendant and as a "sandbar" by the plaintiff. Based on the evidence, I find and rule that the land mass in question was above low water mark, but below mean high water mark and was, therefore, a sandbar prior to the 1903 dredging of Menemsha channel [Note 3] (see Appendix A).

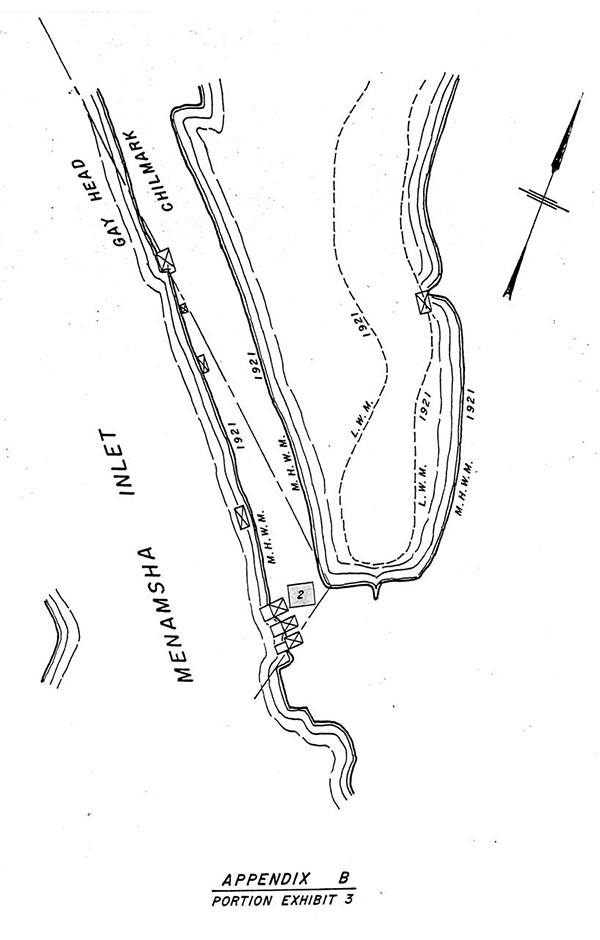

When the Commonwealth dredged in 1903, the topography of Menemsha inlet was changed, and the sandbar ceased to exist. As a result of the dredging, a new spit of land was created in between the new channel and the location of the old channel. (Appendix B).

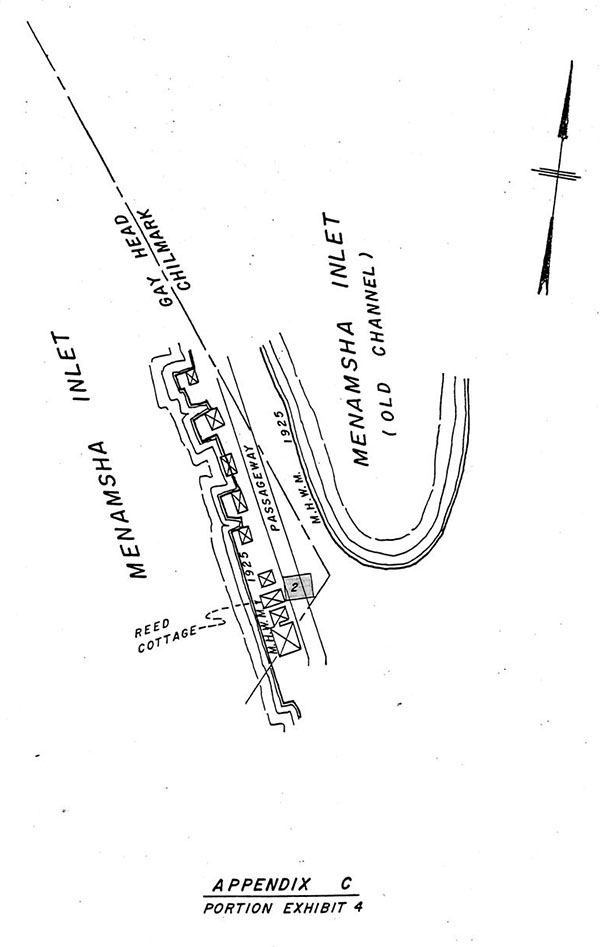

Sometime prior to 1910 at least six cottages were erected in the vicinity of locus. (Flanders deposition, pp. 10-15, Exhibit 24). D. Herbert Flanders and his wife, Hazel C. Flanders, began to use one of the cottages (The Reed Cottage) in 1921, and they continued to use it until 1938. Rodney Reed's son also used the cottage for a period of years between 1921 and 1938. Several cottages appear in 1921 and as of that date the mean high water came up under the Reed Cottage, which was on pilings. (Appendix B). Sometime between 1921 and 1925 there was construction in the area of the locus which included the construction of a bulkhead. Due to the construction of the bulkhead the water no longer came up under the Reed Cottage at mean high water in 1925. (See Appendix C).

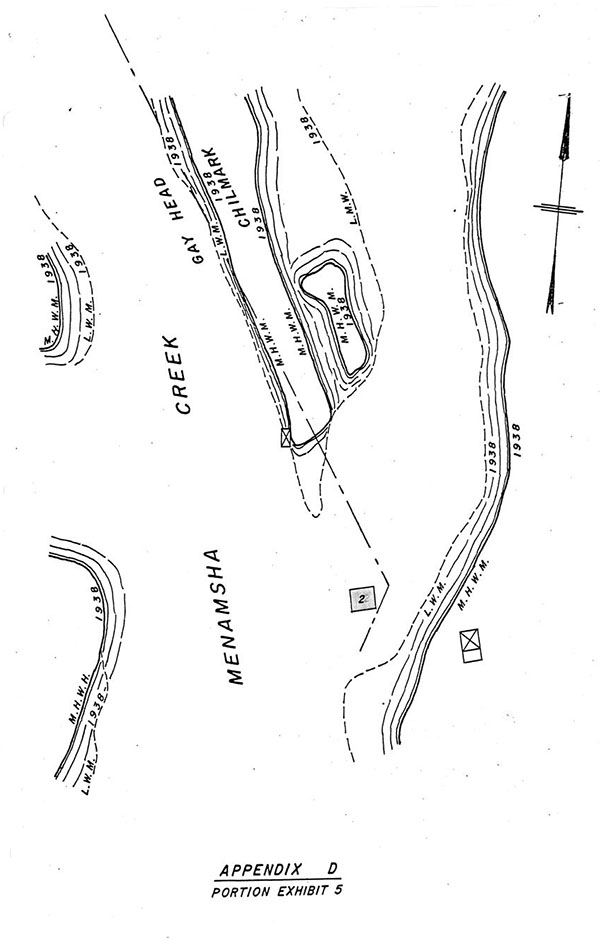

In 1938 a hurricane destroyed all the cottages in the area of Menemsha Inlet, including the Reed Cottage, and washed away the land area in issue. (Appendix D). Following the hurricane the Commonwealth re-dredged the channel, again changing the topography of Menemsha Inlet.

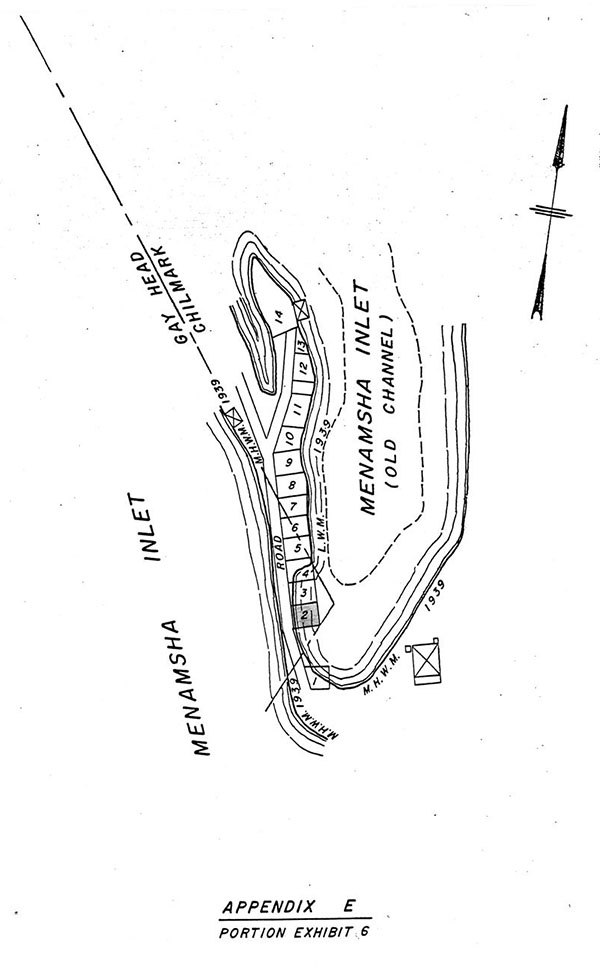

Several topographical changes are apparent from a comparison of Exhibit 5 and Exhibit 6 representing the area in 1938 and 1939, respectively. (See Appendices D and E). Subsequent to the dredging in 1938 the passage which was previously located to the east of the cottages before the hurricane, was relocated to the west of the former location. In addition, the width of the land mass in 1939, subsequent to the dredging, was narrower in the area of Lot 2 than it had been prior to the dredging. Finally, the position of Lot 2 in 1939 was not in the same location as the former Reed Cottage, being slightly to the east.

In 1939 the Flanders built what is now the defendant's cottage (Scuttlebutt) on Lot 2, slightly to the east of the former location of the Reed cottage. Other cottages were also rebuilt in the area. (Appendix E).

Also in 1939, on September 13th, the Commonwealth issued a use and occupancy permit for "an area north of County Rd. at Chilmark and Gay Head." (Exhibit 21). Between 1939 and 1947 six such permits were issued by the Commonwealth to D. Herbert Flanders for which Flanders paid $5 annually. In 1941 the Commonwealth issued Flanders a one year use and occupancy permit for "the area...designated at No. 2 on the plan attached to permit No. 3668 dated September 13, 1939 and marked 'Commonwealth Land Menemsha Gay Head and Chilmark'". (Exhibit 8). Identical permits were issued to Flanders by the Commonwealth in 1942 (Exhibit 9), 1943 (Exhibit 10), 1944 (Exhibit 11) and 1947 (Exhibit 14).

While the land descriptions in the Commonwealth's records of permits issued to Flanders between 1939 and 1947 includes a reference to Chilmark as well as Gay Head and does not contain any metes and bounds description of the land for which the permits issued, the description is sufficiently descriptive of Lot 2 and I find and rule that Flanders applied for, paid for and received use and occupancy permits for Lot 2 from the Commonwealth during 1939, 1941, 1942, 1943, 1944 and 1947.

In approximately 1948 the Commonwealth ceased cashing Flanders' check and shortly thereafter Flanders stopped sending checks and applying for permits.

Between 1938 and 1961, the Flanders used Scuttlebutt for scalloping, fishing, and other activities year round. In fact, during this time period they lived in the cottage from early spring until early fall for several years. In 1954, when the area of Menemsha inlet was struck by another hurricane, the Flanders repaired their damaged cottage, placing it on high pilings.

On October 21, 1961, defendant and his wife purchased the cottage located on Lot 2 from Hazel C. Flanders, Executrix of the Estate of D. Herbert Flanders, who had died earlier that year. At that time the Browns received a bill of sale. The bill of sale transferred to defendant "A one and one-half story building of wooden construction..." The location of the building is described as "situated at Menemsha, Massachusetts, on Lot 2", making further reference to the 1939 map referred to by the Commonwealth in the permits it issued to Flanders during the 1940's. (Exhibit 28). Lot 2 was not listed as real estate in the inventory of Flanders' estate. (Exhibit 33).

On March 4, 1980, during the course of a deposition taken in connection with this suit, Mrs. Flanders signed a confirmatory deed granting to defendant Brown "all my right, title and interest in a certain parcel of land situated in Gay Head, Dukes County, Massachusetts, lying under the building known as the "Scuttlebutt" abutting Menemsha Harbor and north of North County Road." (Exhibit 29). Defendant has not seriously pressed any claim by grant to the locus and, indeed the evidence does not support any rights by grant, and I find that Hazel C. Flanders, Executrix, had title to the cottage only.

In December, 1961, two months after the defendant purchased "Scuttlebutt" the Commonwealth issued a use and occupancy permit to the defendant for the "area ...designated as No. 2 on the plan attached to Permit No. 3668 dated September 13, 1939..." (Exhibit 12). A second use and occupancy permit for Lot 2 issued to the defendant in 1963. (Exhibit 13). Defendant paid ten dollars per annum for the permits.

By letter dated May 5, 1965 defendant requested the issuance of an "annual renewal of a Permit granted to [defendant] by [the Division of Waterways, Department of Public Works] for use of the property described as ...Lot No. 2..." (Exhibit 15).

The Commonwealth subsequently returned defendant's check and failed to issue a permit. Since that time defendant has neither applied for nor received any permits from either the Commonwealth or the town.

There is no question that Brown, his family and guests have used the Scuttlebutt since 1961 on weekends and for vacations. The cottage has been used by them primarily for fishing and entertaining. In approximately 1964 or 1965 defendant added a porch to the cottage. Defendant used the Scuttlebutt for the last time in 1977. Beginning in 1979, he refrained from using it by agreement with the town, pending the outcome of this litigation.

In 1970, by deed without covenants dated April 13th, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, through its Department of PublicWorks, acting under the authority of chapter 485 of the Acts of 1965, transferred to the town a parcel of land, "being a portion of the land excepted from the Original Petition in Land Court Case No. 7706 because of its status as land of the Commonwealth ..." (Exhibit 27). I find that this description encompasses Lot 2. (See Tilton petition).

The town made no effort to prevent defendant's use of the cottage on Lot 2 until commencing this litigation.

In 1979 the town sent to the defendant a ''notice of real estate tax for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1979", which was paid by him on July 17, 1979. The land for which defendant paid taxes is described as ''Menemsha Lot", valued at $1,000 and a "House", valued at $1,000. (Exhibit 17).

While the town's complaint is formally framed in three counts, the case is essentially a writ of entry, brought under G. L. c. 237, and has been argued as such by both parties.

In a writ of entry proceeding, if plaintiff proves by a preponderance of the evidence that it is entitled to the estate set forth in the complaint and that it had a right of entry on the day when the action was commenced, it shall recover the land unless the defendant proves a better title in himself. G. L. c. 237, §5. The town's claim of title derives solely from its 1970 deed from the Commonwealth. The defendant's claim is, in essence, twofold: First, he claims that the town has failed to prove its title by a preponderance of the evidence and, second, he claims that the use of the cottage located on Lot 2 by the defendant and his predecessors in title is superior to all but the true owner and was adverse to the Commonwealth and the town even if it had established title to the locus.

The defendant has also claimed that the town's action is barred by laches. I find and rule that the town, having become record title owner in 1970, has brought this action seasonably and in accordance with G. L. c. 237, §3, and that subsequent to 1970 the defendant has not suffered any detriment as a result of the nine year delay in the town's filing of this suit.

The central issue to the town's claim of title is whether or not the Commonwealth owned the land referred to herein as Lot 2 when it executed the deed to the town. In order to establish the Commonwealth's title the town has introduced into evidence plans, sketches, and maps of the area, showing it at various intervals beginning in 1896.

The town, utilizing the testimony of its expert witness to interpret the documentary evidence, has established by a preponderance of the evidence, and I so find and rule, that the defendant's cottage, located on what is referred to as Lot 2 herein, is located on land that, in 1970, was land of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts by operation of law, and that title to Lot 2 passed to the town by virtue of the Commonwealth's deed to it in 1970.

I have found that in 1903, prior to the Commonwealth's dredging in Menemsha Inlet, the area now known as Lot 2, did not exist on any permanent land mass. The superimposition of Lot 2 on the topography of Menemsha Inlet as of 1903 indicates that Lot 2, had it existed, would have been situated partly on what I have found to have been a sandbar, and partly within the waters of Menemsha Inlet. (Appendix A).

I rule that as of 1903, title to the sandbar as well as title to the land beneath the waters of Menemsha Inlet was in the Commonwealth. See generally United States of America v. 1.58 Acres of Land, Civil Action No. 80-2207-G (Dist. Mass.); Boston Waterfront Corporation v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 (1979); Home For Aged Women v. Commonwealth, 202 Mass. 422 (1909).

There exists an area designated as "proposed channel" on Exhibit 2 and Appendix A, both of which reflect the topography of Menemsha Inlet in 1903. The dredging done by the Commonwealth later in 1903 was done pursuant to navigation purposes and title to all lands created as a result of the dredging vested in the Commonwealth. Home For Aged Women v. Commonwealth, 202 Mass. 422 (1909).

The site of the new channel, as of 1921, is consistent with the site of the proposed channel depicted in Exhibit 2 and an inference can be reasonably drawn, and I so find, that the Commonwealth dredged the new channel according to the plan drawn in 1903.

Exhibit 3 and Appendix B indicate that, in 1921 after the new channel was dredged, Lot 2, had it existed at that time, would have been located on the spit of land that was created by the dredging of the channel.

The topography of the locus changed slightly between 1921 and 1938 (see Appendix C). In 1938 when the area was struck by a hurricane, the spit of land created in 1903 was washed away entirely. Shortly thereafter the Commonwealth, through the Division of Waterways, redredged the channel and fortified the spit of land created as a result of the dredging. I find and rule that, as of 1939, title to land herein called Lot 2, was in the Commonwealth.

Accordingly, despite the fact that the town failed to introduce evidence containing precise metes and bounds descriptions of the location of Lot 2 at all relevant times, I find and rule that it has produced sufficient evidence of the location of Lot 2 and I find it to have been in the Commonwealth's ownership at all relevant times.

Defendant has argued that, even if the town carried its burden of proof as to its title, defendant has established his title to Lot 2 by adverse possession.

There is no merit to this claim.

I rule that the defendant's use of the cottage located on Lot 2 was with the permission of the Commonwealth in 1961 and 1963, as evidenced by the occupancy permits issued to him. I further rule that this permissive use did not become adverse to the Commonwealth at any time subsequent to 1963.

I need not determine whether the defendant's use since 1970 has been adverse to the town because the time period is statutorily insufficient to vest title in defendant in any event.

Neither party has introduced any evidence of the value of improvements, profits, or damages as authorized by G. L. c. 237 and I, therefore, make no awards.

The parties shall bear their respective costs of this litigation.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

exhibit 4

exhibit 5

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The plaintiff claims title by deed from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1970. In order to determine whether or not the town has proven that its claim of title to Lot 2 is superior to defendant's claim of title, it has been necessary to retrace the location of what is herein called Lot 2 to determine whether it is situated in a location to which the Commonwealth had title prior to conveying locus to the town. Appended to this decision are Appendices A-D which are sketches prepared by the engineers of the Land Court representing portions of Exhibits 2, 3, 4 and 5, with the engineers' notations where marked, all of which were rescaled to 1:1000 as a visual aid to this decision. The location of Lot 2, as it has appeared on the ground since 1939, has been superimposed and marked in red on Appendices A-D to show where Lot 2 would have been located in reference to the areas depicted on the appendices. Appendix E is a portion of Exhibit 6, rescaled to 1:1000, with Lot 2 marked in red. This procedure was adopted after consultation between the court and counsel and was, in the opinion of the court, a necessary visual aid since several of the exhibits were drawn to different scales and were difficult to visually compare to one another with any degree of accuracy.

[Note 2] A brief history of this area is set out in the Tilton decision, Land Court Registration Case No. 7706.

[Note 3] Consistent with this finding, the Commonwealth claimed ownership to the sandbar in the Dyer and Tilton cases, although it referred to the land mass as an "island". There was no adjudication as to either ownership or the nature of the land mass in the Dyer and Tilton cases. Even though the referral by the Commonwealth to this land mass as an island in its answer in the Dyer case and its amended answer in the Tilton case is admissable as an evidentiary admission, binding on the Commonwealth's successor in interest, it is not conclusive.