ANNABEL LASOFF vs. SOUTH SHORE BANK, INC.

ANNABEL LASOFF vs. SOUTH SHORE BANK, INC.

MISC 100131

April 22, 1983

Norfolk, ss.

SULLIVAN, J.

ANNABEL LASOFF vs. SOUTH SHORE BANK, INC.

ANNABEL LASOFF vs. SOUTH SHORE BANK, INC.

SULLIVAN, J.

This is an action by Annabel Lasoff, the plaintiff, as owner of a parcel of land, with the buildings thereon, now known as and numbered 417-423 Hancock Street in Quincy, in the County of Norfolk, to establish an appurtenant right of way for all purposes by prescription over a parcel of land about twelve feet wide owned by the South Shore Bank, Inc., the defendant, and shown as A Plot 28 on Quincy Assessor's Map 6004. The complaint alleged use of the latter parcel since at least 1945 by the plaintiff, her tenants and invitees openly, uninterruptedly and adversely until January 18, 1980 when the defendant or parties acting with its consent attempted to close off the plaintiff's access over said A Plot 28. The defendant in its answer denied the use of A Plot 28 as a right of way by the plaintiff and those claiming under her as well as the allegation as to the closing of the way.

A trial was held at the Land Court on October 6 and November 30, 1982 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. The Court took a view in the presence of counsel on December 1, 1982.

On all the evidence, I find and rule as follows:

1. Reserve Security Company acquired title to the premises at 417-423 Hancock Street in said Quincy from Medford Trust Company by deed dated March 28, 1930 and recorded in the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds, [Note 1] Book 1886, Page 265.

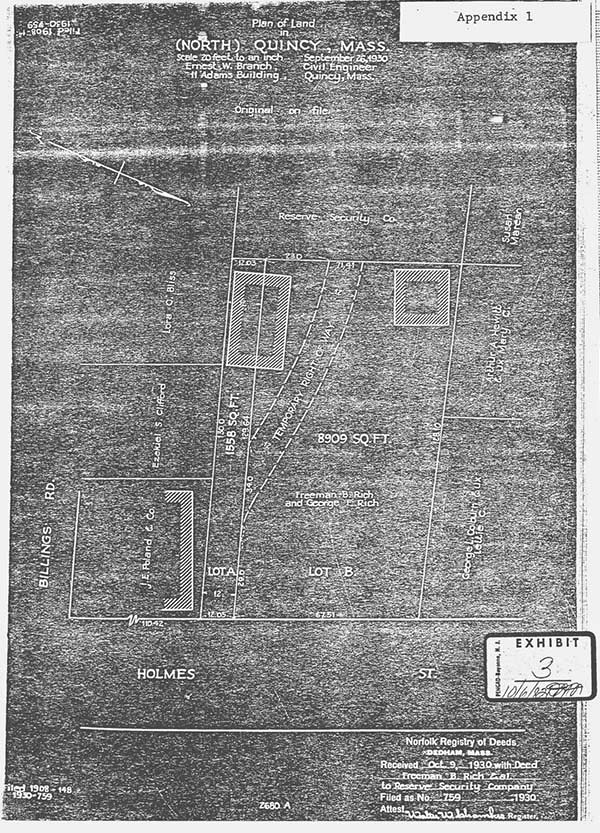

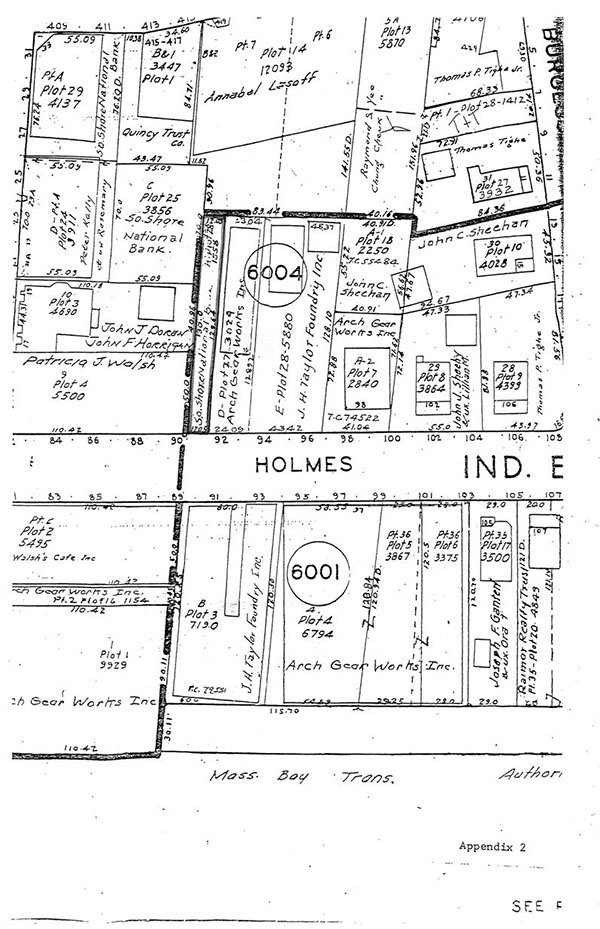

2. Reserve Security Company acquired title to A Plot 28 from Freeman B. Rich, et al, by deed dated October 1, 1930 and recorded in Book 1908, Page 148. The deed describes said strip as Lot A on a Plan of Land in (North) Quincy, Mass. dated September 26, 1930, Ernest W. Branch, Civil Engineer (Exhibit No. 3). The plan was recorded with said deeds as plan No. 759 of 1930, and a copy is attached hereto as Appendix 1. Also attached hereto as Appendix 2 is a copy of a portion of the Assessors' Map (Exhibit No. 17) showing the Hancock Street premises as Plot 14, Lot A as Plot 28, and other land of the defendant as Plots 25 and 29.

3. The Rich deed recites that Lot A was partially covered by a wooden building which the grantors agreed to remove within two years and made provision for a temporary right of way for the grantees until such removal. The deed also reserved for the benefit of Lot B on said plan a right of way over Lot A.

4. Title to 417-423 Hancock Street and Lot A diverged in 1936 when Medford Trust Company foreclosed its mortgage on the Hancock Street parcel. Title then passed in 1940 to Samuel Neustadt and Bella Neustadt, husband and wife, as tenants by the entirety by deed recorded in Book 2283, Page 327. Mr. and Mrs. Neustadt were the parents of the plaintiff, and after Mr. Neustadt's death the surviving tenant by the entirety conveyed the Hancock Street premises to the plaintiff by deed dated December 28, 1967 and recorded in Book 4484, Page 377.

5. The mortgage to Medford Trust Company was executed and delivered prior to the acquisition by Reserve Security Company of Lot A and did not include it; title thereto did not pass, therefore, to the mortgagee's successors in title. Rather the City of Quincy took it for non-payment of real estate taxes from Reserve Security Company, foreclosed the taxpayer's right of redemption in Land Court Miscellaneous Case No. 23403 and conveyed the property to Richard D. Barry, Jr. by deed dated December 27, 1945 andrecorded in Book 3311, Page 420 who in turn conveyed Lot A to the defendant's predecessor corporation Granite Trust Company by deed dated January 21, 1946 and recorded in Book 3311, Page 421 (Exhibit No. 2).

6. As the Assessors' Map (Exhibit No. 17) makes apparent, the plaintiff's building(s) completely occupy the entire frontage of her property on Hancock Street, and access to the rear thereof can be gained only by passing over Lot A from Holmes Street which runs roughly parallel to Hancock Street. At the present time, it also is physically possible to proceed from Burgess Street which is perpendicular to Hancock Street, across land of two third parties to the rear of the plaintiff's building. There is no record right of way for the benefit of the plaintiff's property to use such route. Formerly there was a wire fence which prevented passage over land of the adjoining owners to Burgess Street. Remains of the fence were apparent at the view. It has only been during the last four or five years that the fence has been removed.

7. Hancock Street, on which the plaintiff's property is located, is the main thoroughfare in Quincy. It extends from the Neponset River to the end of Quincy Square. Approximately two miles beyond the plaintiff's property on Hancock Street in the square is the defendant's main office. A branch bank of the defendant is located at the junction of Hancock Street and Billings Road, and between it and land of the plaintiff is the office of another bank. The Assessors' Map also shows other parcels of land owned by the defendant at the rear of Billings Road and Hancock Street. On the opposite side of the plaintiff's property from the defendant's branch is a Chinese restaurant. In the plaintiff's buildings there are commercial tenants on the first floor and at times in the basement, and eight apartments on the second floor. There is access from the apartments onto a fire escape which runs along the rear of the building on the second floor with the fire escape stairs leading to the ground. There also is dumpster in the large rear yard behind the building, and room for several cars to park (Exhibit Nos. 7 and 8). There is no way to reach the rear yard of the plaintiff's property from Hancock Street, either by foot or by car without passing over the land of others.

8. The plaintiff testified that she worked for her father in the management of his real properties of which there were approximately twenty to twenty-five, from the time she was in high school. He and her mother purchased the Hancock Street property in 1940, and between 1940 and 1949 she visited the premises approximately two to three times per month. Her brother also worked for their father. In 1951 she opened a retail store called Annabel's Dress Shop in one of the stores and ran it for three years before it was sold. During this period she was present nearly every day. At that time the second floor had commercial tenants also, and she helped collect the rents and do other jobs assigned by her father in managing and maintaining the property. Her father converted the second floor to apartments about 1945 or 1946 and the fire escape was added at that time. She continued her part time managerial duties as did one of her brothers during this period, and she took over full time in 1967 assisted by her husband and son.

9. Parking on Hancock Street being difficult, the plaintiff would approach the site by driving down Billings Road (which runsroughly parallel to Burgess Street and perpendicular to Hancock Street) to Holmes Street, would turn on Holmes Street and proceed to Lot A where she would turn onto it and drive over Lot A to the rear yard of her buildings. She would leave the vicinity by following the same route. During the years the City of Quincy collected the rubbish, the city truck would come into the yard over Lot A, and after this service was discontinued by the municipality, the private collection of rubbish was and is carried out by the trucks coming in the same way. Two 1968 statements addressed to the plaintiff and showing payment for rubbish removal were introduced into evidence as Exhibit Nos. 18B and 18C. Deliveries to tenants were made at the back, and residential tenants drove in and out over the same route.

10. The plaintiff claimed that repairs had been made to Lot A and snow removed by or on behalf of her parents or herself, but witnesses for the defendant testified that they were not aware of such activities. There was no direct evidence introduced by the plaintiff to support her testimony, for bills for snow removal after the Great Blizzard of 1978 and for five tons of gravel may relate only to the rear yard of the Hancock Street premises (Exhibit Nos. 15 and 14).

11. For many years there was a large furniture store at the corner of Billings Road and Holmes Street, the rear of which was toward Lot A. Trucks making deliveries to Dudley Furniture at times used Lot A and occasionally blocked it or made access temporarily difficult. Usually, however, deliveries were made to or from the rear door on the Holmes Street side of the building. Arch Gear, the southeasterly abutter of Lot A, also used Lot A for deliveries to its building, but it appears to have a record right to do so as, thepresent owner of the former Rich property. Joseph Doran and John Horrigan, who own a property fronting on Billings Road in which they conduct their real estate and insurance business, testified that for eighteen years they had used Lot A to pass and repass to and from Holmes Street and the rear of their property to park their cars. Their use had never been interrupted except for a short period in 1980.

12. In 1980 several large boulders or pieces of concrete or granite were placed across the way and blocked access to the rear of the plaintiff's property (Exhibit No. 5). The plaintiff protested to the police and fire departments and to others, and the barrier was removed. It was about this time that she first learned the defendant was the owner of Lot A. About this time also Andrew Walsh, proprietor of Walsh's Restaurant on the opposite corner of Billings Road and Holmes Street, acquired the parcel for restaurant parking on which Dudley Furniture stood before it was destroyed by fire. The parking lot was paved, and a guard rail installed on the southeasterly side of Lot A which has since been moved to the northwesterly side (Exhibit Nos. 5 and 6 ). The paving reached to the concrete wall shown in the photographs which is around other property of the defendant at a higher elevation than Lot A. The testimony was not entirely clear as to whether it was Mr. Walsh who caused the obstruction to be placed on Lot A with the consent of the defendant.

13. Both the plaintiff and Mr. Walsh have offered to buy Lot A from the defendant, which offers have been refused.

14. The plaintiff's tenants also have passed to and from Holmes Street and her property over Lot A.

The fundamental question to be decided here is whether the plaintiff has acquired an easement by prescription to pass and repass, on foot and in vehicles over Lot A. The defendant attempted to discount the plaintiff's testimony by introducing evidence as to the availability of an alternative access route to the rear yard of the plaintiff's property and by testimony of other area property owners as to limited use of Lot A. The defendant also points to case authority which would negate use by the plaintiff's tenants as evidence of her prescriptive use.

The rule as to acquisition of an easement by prescription hardly needs to be given as it is so well established in this Commonwealth. In brief, the party claiming the easement has the burden of proving that his use has been "open, uninterrupted and adverse for a period of not less than twenty years." Tucker v. Poch, 321 Mass. 321 , 323-4 (1947); G.L. c. 187, §2. He need not show that his possession is exclusive as that term is used in adverse possession, but "[h]e must show that his use has been exclusive in the sense that he relies on his own use or those under whom he claims and not on the use by third parties." Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 349 (1967). Yet the "[u]ses of the way by third persons for purposes primarily beneficial and appurtenant to the dominant estate may be taken into consideration in deciding whether an easement by adverse use has been acquired ...." Abbott v. Mars, 277 Mass. 122 , 124 (1931); Brown v. Sneider, 9 Mass. App. Ct. 329 , 331-2 (1980). ''... '[W]herever there has been the use of an easement for twenty years unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription unless controlled or explained." Ivons-Nispel, Inc. v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 762-3 (1964), citing Flynn v. Korsack, 343 Mass. 15 , 18 (1961) accord, American Oil Co. v. Alexanderian, 338 Mass. 112 , 115 (1958).

The plaintiff's testimony, if believed as I do, showed use of Lot A for access to the rear yard of the Hancock Street property from at least 1940 to the present, interrupted for only a few days in 1980. The use consisted of vehicular passage by the plaintiff, originally as an agent of her parents and later as the owner, and by those commercial and residential tenants of her building, business invitees of the tenants and of the plaintiff, including rubbish collectors as well as foot passage by the tenants. A branch office of the defendant is close by, and its main office not far away by today's standards. The use by the plaintiff, her predecessors in title and business invitees was apparent, and the defendant should have known thereof. I accept the plaintiff's testimony as to use of Lot A as a way and find that she has borne her burden of proof. The yard of 417-423 Hancock Street is in effect a landlocked parcel which can be reached on foot or by motor vehicle only by crossing land of others. An attempt was made by the plaintiff's predecessor in title to cure the problem in 1930 when the then owner of the Hancock Street premises acquired title to Lot A. It is clear from the deed to Reserve Security Company that it was designed to afford access to what is now the plaintiff's property as well as providing right of way for the remaining land of the grantors. The financial woes of the depression era - a mortgage foreclosure and taking for non-payment of real estate taxes led to a separation of ownership which has continued. I find and rule, however, that the use of Lot A did not change with the mortgage foreclosure, and that it has always been used to afford access to the plaintiff's rear yard.

The history of the record title, therefore, corroborates the plaintiff's testimony as to the location of the access. There never was any right of way by record, permission or otherwise, from Burgess Street over land of two third parties to the plaintiff's property shown by the defendant and the fact that it now physically can provid access (but without right) is immaterial. Absent any evidence that it in fact was so used in years past put no weight on the possibility of an alternative route, which could, but was not shown, to have been used. I further find that the credibility of the plaintiff's evidence is not lessened thereby.

The plaintiff has owned the property only since 1967, but the defendant does not dispute the fact that the adverse use during her parents' ownership may be tacked, Wishart v. McKnight, 178 Mass. 356 (1901), but rather disputes the proof of such use during the entire period in question. In particular it is argued that use by the tenants of the plaintiff and her predecessors does not aid the plaintiff's case since the leases to them were not shown to include a demise of such right. See Holmes v. Turner's Falls Co., 150 Mass. 535 (1890) and Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 (1949). Each of such cases is distinguishable on the ground among others, that a fee rather than an easement, was sought. It is true, of course, that the plaintiff cannot benefit from the use of the strip by anonymous members of the public. Ivons-Nispel, Inc. v. Lowe, supra, or by other owners of land abutting thereon. Labounty v. Vickers, supra. On the other hand it has long been settled, as noted above, that use by third persons for purposes beneficial to the dominant estate may be taken into consideration.

The plaintiff claimed the benefit of a prescriptive easement to use Lot A for all purposes. The evidence shows only use for foot and vehicular passage. An easement by prescription is fixed by the use through which it is created, and the plaintiff's rights, therefore, are limited to the uses shown to have been made. See Stucchi v. Colonna, 9 Mass. App. Ct. 851 (1980).

On all the evidence I find and rule that the owners of the premises at 417-423 Hancock Street and those claiming under them as agents, employees, tenants, business invitees and the like have used Lot A openly, uninterruptedly, adversely and notoriously for aperiod from at least 1940 to 1980; that the defendant did not commit or cause to be committed any overt act to prevent the acquisition of the easement, Brown v. Sneider, supra, until 1980 when it was too late; and that the prescriptive rights obtained by the plaintiff, as appurtenant to the premises conveyed to her by her mother, are limited by the uses made of Lot A, that is, to the right to pass and repass, on foot and in vehicles, to and from Holmes Street and the dominant estate.

The findings of fact and rulings of law requested by the plaintiff are granted other than the request for finding of fact No. 4 to which the evidence is not clear.

Judgment accordingly.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] All recording references herein are to said Deeds.