Walter Bushmick, John W. Buckley and John E. Maloney, as Trustees under a Declartion of Trust dated November 26, 1971

and recorded with Middlesex South District Deeds Book 8304, Page 395 (the "Plaintiffs") brought this complaint pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 240, §14A and c. 185, §1 (j 1/2) to determine the validity of §5.09 of the Woburn Zoning Ordinance, as amended on May 17, 1981. The plaintiffs claim to be the ownrs of land zoned for industrial use in Woburn in the County of Middlesex and so located in relationship to an area zoned for residential uses that their land is affected adversely by the 1981 amendment to the zoning ordinance. Thereafter Richard L. Pinkham ("Pinkham") moved to intervene pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 24 (b) as a party plaintiff and his motion was allowed. Pinkham alleged that he was the owner of land situated on Dragon Court in said city adversely affected by said amendment. Thereafter Albert F. Curran, Trustee of the B & C Realty Trust ("B & C") made a similar motion to intervene which was allowed. The complaint on behalf of B & C alleges ownership of two lots of land situated on Draper Street in Woburn and adversely affected by the amendment to the zoning ordinance. The fourth complaint on behalf of interveners was brought by John F. Gilgun, Jr. and Rosemarie Gilgun ("Gilgun") after allowance of their motion to intervene, and alleges ownership of land at the intersection of Mishawum Road and Washington Street also allegedly adversely affected by the zoning change. The parties all contend that §5.09, as amended, is invalid on its face as a taking of property without compensation in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and Articles 10 and 11 of the Declaration of Rights of the Massachusetts Constitution and as being without the authority conferred by G.L. c. 40A in that the amendment allegedly is arbitrary and unreasonable and without substantial relationship to the public health, safety, or general welfare. The City of Woburn in its answer contends that §5.09 does not conflict with either the federal or state Constitutions or the Enabling Act and that its actions at all times were reasonable.

A trial was held at the Land Court on November 15 and 17, 1982 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. At the commencement of the trial a statement of Agreed Facts executed by the plaintiffs and the City was introduced in evidence as Exhibit No. 22 and reads as follows:

1. Plaintiffs, Walter Bushmick, John W. Buckley and John E. Maloney are Trustees under a Declaration of Trust dated November 26, 1971, recorded in Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds in Book 8304 at Page 395.

2. Plaintiffs as Trustees are the record owners of the property that is the basis of this lawsuit, located at Wildwood Avenue, Woburn, Massachusetts.

3. The property owned by the Plaintiffs is bounded and described per Exhibit A attached hereto and incorporated herein.

4. That this action is brought under Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 240, Section 14A and Chapter 185, Section 1 (j 1/2) to determine the validity of City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 5.09.

5. That the Plaintiffs' property is located in an Industrial Zone as designated by City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 2.00 as amended.

6. That the Plaintiffs' property borders a Residential Zone as designated by the City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 2.00 along its Southerly and Southwesterly borders for a distance of 1337.02 feet.

7. That the City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 5.09 as amended on May 17, 1981, reads as follows:

Along each boundary of an "S" and "B" district which adjoins any "R" district there shall be a buffer zone of 20 feet in addition to the minimum side and rear setbacks. Along each boundary of an "I" district which adjoins an "R" district there shall be a buffer zone of 150 feet in addition to the minimum side and rear setbacks. This buffer zone will extend from the boundary line into the I zone. If the boundary line between the residential and industrial land falls on a street, the whole width of street should be used for calculation of 150 feet - street shall not include paper street.

This buffer zone shall contain a screen of plantings in the center of the strip not less than 3 feet in width and 6 feet in height at the time of occupancy of such lot. Individual bushes or trees shall be planted not more than 3 feet on center, and shall thereafter be maintained by the owner or occupants so as to maintain a dense screen year-round. At least 80% of the plantings shall consist of evergreens. A solid wall or fence, not to exceed 6 feet in height, may be added to such landscaped buffer strip if required by Building Inspector or Planning Board or Board of Appeals of City Council.

8. That City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 5.09, prior to the May 17, 1981 Amendment, required a 20 foot landscaped buffer zone between a Residential Zone, Industrial Zone, mixed Use Zone, and Business Zone, all as defined by City of Woburn Zoning Ordinance, Section 2.00.

9. That Plaintiffs' parcel of land contains approximately 7.80 acres.

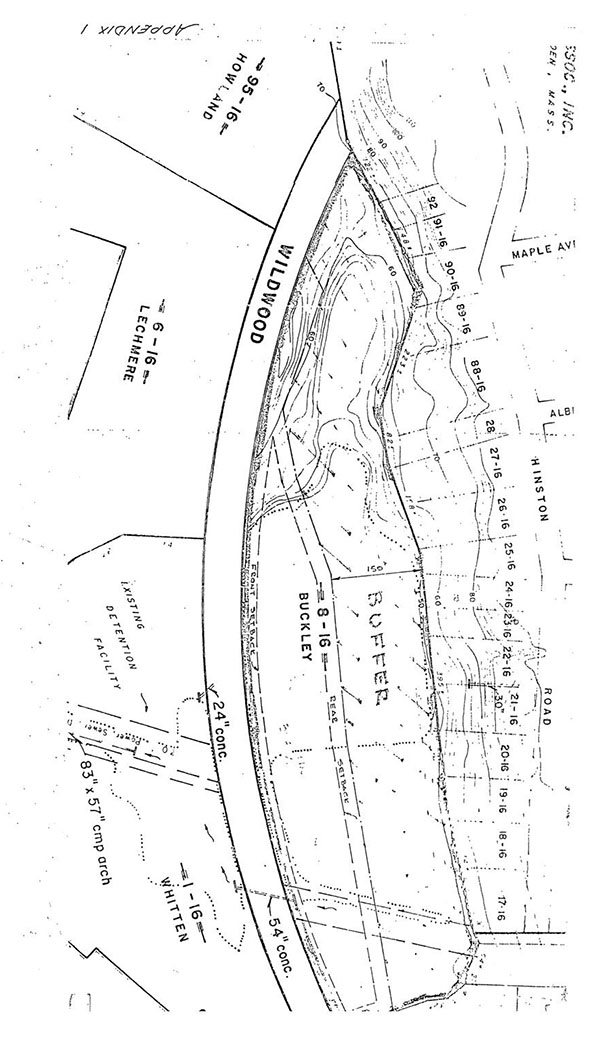

10. That approximately 4.50 acres of Plaintiffs' parcel of approximately 58% of Plaintiffs' land consisting of a strip of land 150 feet in width along its Southerly and Southwesterly border in addition to the setback requirements is affected by Section 5.09 of the Zoning Ordinance as amended. (See Exhibit B attached). [Note 1]

11. That the assessed value for Plaintiffs' property located on Wildwood Avenue in Woburn, Massachusetts is $105,150.00.

12. That the 25 foot side and rear setbacks are required in addition to the buffer zone requirements per Section 5.09 of the Zoning Ordinance.

13. That on February 4, 1982, a Notice of Intent regarding the property was filed with the Woburn Conservation Commission.

14. That on April 22, 1982, the Woburn Conservation Commission issued an order of conditions on the Plaintiffs' property.

15. That the order of conditions was recorded with the Middlesex South District Registry of Deeds on April 30, 1982 in Book 14597 at Page 107.

16. That the order of Conditions required a retention area as shown on a plan entitled "Site Plan of Land in Woburn, Mass." dated May 1, 1981, revised March 17, 1982, by F. D. Dewsnap Engineering Assoc., Inc. Scale 1"=40', stamped by Frederick P. Dewsnap, RPE and "Plan of Land in Woburn, Mass.", showing section details as site plan, daed June 15, 1981, revised March 17, 1982, by Frederick P. Dewsnap RPE.

Although the interveners were not parties to the Statement of Agreed Facts, the provisions set forth in paragraphs 4, 5, 7, 8 and 12 thereof apply equally to all parties. None of the parties attack the adoption of the amendment on procedural grounds but complain only of the substance. Both Pinkham and Curran entered into stipulations with the City relative to the admissibility of certain plans and drawings relating to their respective property and to their ownership of the land described in their Complaints.

Exhibit A referred to in paragraph 3 above set forth the legal description of the land of the plaintiffs as follows:

EXHIBIT A

A certain parcel of land situated on Wildwood Avenue in the City of Woburn, Middlesex County, bordered and described as follows:

Easterly by Wildwood Avenue 1505.04 feet.

Southerly by land of others 95.06 and 148.06 feet respectively.

Westerly by various courses respectively 223.36 feet, 82.56 feet, 158.73 feet, 395.21 feet, 234.04 feet, 54.54 feet.

Northwesterly 40.00 feet.

Northerly by two courses 31.65 feet and 153.29 feet respectively.

On all the evidence, I find the facts agreed to by the parties and I also find and rule as follows:

1. The land of the plaintiffs is an elongated parcel with a frontage on Wildwood Avenue of 1505.04 feet and a width of about 300 feet at its widest point. It abuts a Residential District on its southerly and westerly boundaries. With the Conservation Commission requirements there remain only 1.9 acres of the total area of 7.80 acres for construction.

2. Prior to the adoption of the amendment to the ordinance, the plaintiffs had executed an option agreement with one Michael Howland, a local developer, to purchase said parcel at a price of $140,000. Mr. Howland had planned to construct a 64,000 square foot building, but with a buffer 150 feet in width, he is of the opinion that a building containing 12,500 square feet is the largest which can now be built. There is some question as to whether even the smaller building can be placed on the lot. He is unwilling to exercise his option if the buffer zone is valid.

3. The costs of construction including that of the fill required for this site make it economically unfeasible to develop it with the small building which can now be placed thereon. See Exhibit No. 13 for a depiction thereof.

4. An appraiser testified that prior to the adoption of the ordinance the value of the parcel was $17,000 per acre and that thereafter it was $32,300 for the entire piece.

5. The effect of the 150 foot buffer zone on the plaintiffs' parcel is graphically shown on Exhibit Nos. 11 and 12.

6. Richard L. Pinkham is the owner of a parcel of land roughly in the shape of a trapezoid situated in an Industrial District, but abutting on a private way called Dragon Court where the boundary line between an Industrial and Residential District falls. The Complaint alleges that said parcel contains about 35,325 square feet of which the buffer, if applicable, comprises 23,325 square feet with the remaining 12,000 square feet or less than one-third of the area available for the uses for which the parcel is zoned. Exhibit No. 16, however, gives the area as containing approximately 45,600 square feet of which only 7,500 square feet is available for development after set-back and buffer provisions are complied with. There are two two-story wood frame buildings on the parcel, one larger than the other, and a shed. Portions of the buildings are used for residential purposes, but the office and place of business of Trim-A-Roofing also are located thereon. The company has three pickup trucks, two "estate" bodies, two dump trucks, three cars, a Mack truck, a van, two tankers and a large, basically a box truck for transporting materials. The vehicles pass to and from the property several times a week with traffic varying with the nature of the vehicle and the construction site where the company has a roofing job. The present operation is protected as a non-conforming use so far as the buffer zone provisions are concerned. Land of the adjoining owner may be used for industrial development by virtue of the recording of a subdivision plan; there were negotiations for his purchase of the Pinkham land until the adoption of the buffer. An appraiser testified that exclusive of improvements the value of the land prior to May 17, 1981 was $2.50 per square foot or approximately $102,800 and that after the adoption of the ordinance it was approximately $35,000 with the existing improvements. The impact of the buffer is shown on Exhibit Nos. 16 and 17.

7. Albert F. Curran, Trustee of the B & C Realty Trust is the owner of'two parcels of land situated on Draper Street, title to which was confirmed in Land Court Case No. 35572 as part of a large tract of land. The disposition of the remainder of such land is unclear, but the intervener Curran complains only of the effect of the buffer zone on lots A and B. The position of these lots is shown on Exhibit No. 18. [Note 2] Prior to the imposition of the buffer zone each lot would support a 40,000 square foot building, whereas after the adoption of the amendment, only a 3,500 square foot building would fit onto Lot A and a 4,700 square foot building on Lot B. [Note 3] The appraiser valued Lot A's pre-ordinance value at $1.75 per square foot or $125,800 and $.55 per square foot (or $2 of usable area) thereafter, i.e. $39,500. Lot B's pre-ordinance value was given as $164,000 with the square foot value reduced to $.55 per square foot or $2 per square foot of usable area thereafter. The adjoining residential land is at a much higher elevation than the Curran land so the uses on the Curran land would not be readily apparent.

8. John F. Gilgun, Jr. and Rosemarie Gilgun are the owners or a triangular parcel of land on Mishawum Road originally containing about 14,000 square feet of land but somewhat reduced in area by a taking by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Both the opposite side of Mishawum Road, the abutting paper Forest Avenue and adjoining land are zoned for residential purposes so the entire Gilgun parcel falls within the buffer zone. One of the owners, Mr. Gilgun, who is a real estate broker testified that the parcel had a value of $10 per square foot prior to the adoption of the ordinance, and that it had none thereafter. His opinion as to value was premised on lease of the parcel, but he had been refused previously a license for a so-called fast food operation on the ground or general traffic congestion in the area. The Gilgun parcel is situated in an I-1 district where the minimum lot size is 20,000 square feet (Exhibit Nos. 2 and 33) and there was no evidence as to whether it was protected as a non-conforming lot. It does adjoin land of one Doherty also zoned as I-1.

9. The Woburn 1970 Zoning Ordinance (Exhibit No. 2) has no definition of a buffer zone. The Building Inspector in an affidavit filed with the Court (Exhibit No. 32) stated that it was his interpretation of Section 5.09 that "with the exception of shrubs and trees, nothing can be erected in the Buffer Zone. Further, the Buffer Zone cannot be used for anything. Specifically the Buffer Zone cannot be used for roadways, parking, outside storage, or for space for large vehicles to maneuver in."

10. Section 5.00 of the ordinance sets forth the Table of Height, Area, and Bulk Regulations. In addition to the minimum lot size of 20,000 square feet in an I-1 District already referred to and 10,000 square feet in an I-2 District, there are front, rear and side yard requirements of 25 feet in an I-1 District and 20 feet in an I-2 District. Maximum building ground coverage is 50% in each district (subject to applicable parking requirements of Article VII) and the minimum street frontage is 100 feet. In addition, there is a provision not here in question set forth in said Table of 10% Minimum Landscaped Usable Open Space in both types of Industrial Districts. The definition of "Usable Open Space" as it appears in Article XI Definitions is:

USABLE OPEN SPACE: Space in a yard or within a setback area on a lot that is unoccupied by buildings, unobstructed to the sky, not devoted to service driveways or off-street loading or parking spaces and ways or off-street loading or parking space, and available to all occupants of the building on the lot.

While the ordinance is silent on this question, it would appear that land within the buffer zone would qualify as usable open space.

11. Section 7.04 of the ordinance provides that all parking or loading areas containing over five spaces, if not contained within a structure must be "effectively screened on each side which adjoins or faces the side or rear lot line of premises situated in any "R" district. The screenings shall consist of a solid fence or wall not less than 3 ft. nor more than 6 ft. in height or shrubbery planted not less than 3 ft. apart on center, at least 2 ft. from the lot line and all maintained in good condition."

12. There is no definition of buffer zone or the uses, if any, to which it can be put set forth in the Woburn ordinance. The only references to it directly appear in said Section 5.09 set forth above.

Each of the plaintiffs argues that §5.09 is not a legitimate exercise of the police power and is invalid. If that not be so, the plaintiffs further argue that the ordinance as applied to the peculiar nature of their parcels cannot withstand attack and is unconstitutional as a taking of their property without compensation.

The authority of any community to enact zoning ordinances and by-laws rests on the enabling act and the police power which must be exercised to further the public health, the public safety and the public welfare. When a zoning ordinance is attacked, the burden is on the plaintiffs to show that the terms of the ordinance are clearly arbitrary and unreasonable. MacNeil v. Avon, 386 Mass. 339 , 340-341 (1982). Every presumption is made in favor of the ordinance, and its enforcement is only refused if it is shown beyond a reasonable doubt that it conflicts with the Constitution or the enabling statute. "Where the reasonableness of a zoning by-law is fairly debatable, then the judgment of the local legislative body upon which rested the duty and responsibility for its enactment must be sustained." Caires v. Building Commissioner of Hingham, 323 Mass. 589 , 594-595 (1949). In applying such principles the appellate courts have upheld one acre minimum lot requirements, Simon v. Needham, 311 Mass. 560 (1942) two acre minimum lot requirements, Wilson v. Sherborn, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 237 (1975) and two hundred foot minimum frontage, MacNeil v. Avon, supra, but have found invalid minimum height regulations, 122 Main Street Corp. v. Brockton, 323 Mass. 646 , 651 (1949) and ten acre minimum lot requirements Aronson v. Sharon, 346 Mass. 598 (1964).

There is only one appellate case in Massachusetts in which the validity of a buffer zone was raised. In Farmer v. Town of Billerica, Mass. (1980) [Note 4] a town meeting article was proposed to rezone a certain area from residential to general business. During debate on the article an amendment was adopted which appeared to create a "no man's buffer zone" between the new business zone and adjoining residential land. However, the Court construed the amendment as creating "a buffer zone next to the newly created general business district by maintaining in effect the then-existing zoning." In reaching this decision the Court said that "There is no indication that the town meeting intended the land to be useless or that it intended to take the plaintiff's land." At the time the amendment was adopted, the plaintiffs' land was primarily zoned as residential. Construing the zoning change in order to avoid "its illegality and its possible unconstitutionality" the court concluded that the town meeting intended to retain the existing zoning within the area delineated as the buffer zone. The court therefore did not consider the construction of the phrase "buffer zone" nor the constitutionality of creating one in which no activities permitted in the underlying district might be pursued.

We did find one case in another jurisdiction in which the New Jersey Supreme Court, in reversing summary judgment below, upheld, at least in the initial decisional stages, the validity of a municipal ordinance which required the owner of a parcel of land having an area in excess of ten acres, and upon which was to be built one or more retail stores, to provide a buffer strip one hundred feet in depth along side and rear lot lines adjacent to residential uses or zones which, as distinguished from the lower court, it interpreted as applying even though the latter in the case at point were situated in another community. Quinton v. Edison Park Development Corp. 59 NJ 571 (1971). The Court stated that the hundred foot requirement did not appear to be unreasonable on its face and that the requirement appeared reasonable in applying to large tracts adjacent to residences which were to house substantial retail business operations. See also State of New Jersey v. Gallop Building, 103 NJ. Super. 367 (1968).

In Farmer, as here, there was no definition of a buffer strip in the by-law, and I construed it as follows:

The zoning by-law contains no definition of a buffer zone. Yet because a term is undefined in a bylaw does not necessarily mean that it is vague and therefore constitutionally infirm. See Board of Appeals of Hanover v. Housing Appeals Committee in Dept. of Community Affairs, 363 Mass. 339 , 363-64 (1973). The Appeals Court recently decided in Langevin v. Superintendent of Public Buildings of Worcester, 5 Mass. App. Ct. 892 (1977) that

The meaning of those words, being undefined by the ordinance, are to be determined 'according to the common and approved usages of the language.'

Accord, Jackson v. Building Inspector of Brockton, 351 Mass. 472 , 475 (1966); Moulton v. Building Inspector of Milton, 312 Mass. 195 , 197-98 (1942). A buffer zone has been defined as "One that protects by intercepting or moderating adverse pressures or influences," or "something that interposes between two rival powers, lessening the danger of conflict. Often used attributively: a buffer zone." American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language 173 (1969). And, in the instant case, it can be said that the Billerica buffer zone must have been intended to separate the business and residential districts and shield the latter from the adverse incidences of the former. Such appears to be the interpretation adopted by the Building Commissioner, and it logically follows that in implementing the by-law, town officials would have to prohibit building and other uses of the parcels within the buffer.

I similarly construe the Woburn ordinance although as I have found above the land within the buffer may be used as credit against the 10% open space requirement. This construction accords with the history of the ordinance whose enactment came after political protests of the contemplated development by the residents of residential districts which abutted existing industrial districts; it seems clear that it was intended to lessen the impact of industry on existing homes by creating a strip 150 feet in width adjacent to the industrial-residential district line and entirely situated within the industrial zone. The correct interpretation of the language of section 5.09 is not free from doubt, but I have construed it as applying to all such district boundary lines whether situated in the front, rear or side of any parcel although it is only as to the rear or side setbacks that the minimum yard requirements must be added to the 150 foot requirement. The City argues that the buffer zone provision is inapplicable if the line falls at the front of a lot since the section refers only to the minimum side and rear setbacks. The first sentence of the section can be so read, but the last sentence of the first paragraph which includes the width of a street as part of the required 150 foot buffer if the district boundary line falls within the street militates against this construction.

The City also argues that the buffer zone may be used for parking, but the practical difficulty of complying with the screening provisions of §5.09 and §7.04 lead me to conclude that the draftsmen did not so intend. I therefore find and rule that other than its use to meet the 10% Minimum Landscaped Usable Open Space owners of land situated as is that of the plaintiffs in an Industrial District at its boundary with a Residential District can make no use of a strip one hundred fifty feet in width which may extend from more than one lot line depending on the shape and location of the land where it abuts a residential district.

In Farmer the peculiar town meeting history was a factor I weighed in upholding the buffer. The Supreme Judicial Court was able to construe the town meeting votes in such a way that the effect of the action was not to leave the area unavailable for use but merely to retain the pre-existing zone. That result cannot be reached here where there is a different pattern of adoption.

After a careful consideration of the provisions of section 5.09 of the ordinance, the enabling act and the language of Farmer, I find and rule on all the evidence that the City has gone beyond what protection of the public interest requires and that a buffer zone of 150 feet cannot be upheld.

St. 1975, c. 808 rewrote the Zoning Enabling Act found in General Laws c. 40A. Section 2A of the 1975 legislation suggests objectives for which zoning may be established by cities and towns and provides a nonexclusive list of possible regulations including those relating to density of population, intensity of use, accessory facilities and uses such as vehicle parking and loading, landscaping, and open space. Section 4 of Chapter 40A permits the division of cities and towns into districts and provides for uniformity within districts. There is nothing in Chapter 40A, however, which suggests that at a district line the less restricted land abutting it may be impressed with the burden for the benefit of the adjoining more restricted land with the result that a substantial strip exists in a vacuum and may not be used for any purpose. At the trial there was no showing that creation of such buffer zones would in any way serve a valid public interest. It may be that the buffer truly would lessen noise, lights and the impact of other industrial activities on the nearby residents. If the City Council in Woburn so concluded and believed that a green belt between districts was desirable, it could have reached such result by taking the land and compensating the owners or by relocating, if appropriate, the district boundaries. As it is, the owners of industrial land adjoining that zoned for residential purposes must devote a substantial portion of their properties to nonuse in order to satisfy their neighbors in the adjoining district but without any showing in this proceeding of concommitant public interest. Under such circumstances the ordinance, clearly unconstitutional, cannot stand. Aronson v. Sharon, 346 Mass. 598 (1964); Pittsfield v. Oleksak, 313 Mass. 553 (1943).

If I am wrong, however, and the buffer zone serves a legitimate public interest and is a proper exercise of the police power, the plaintiffs argue that as applied to their particular parcels it results in a taking of their property without compensation. It is difficult for a landowner, however, to prove that such is the result. The rule was recently restated in MacNeil v. Avon, supra, where it was said:

In the alternative, a landowner may prove a zoning bylaw unconstitutional by demonstrating that it results in a taking of his land without compensation, and is not merely a regulation of the use of his land as a legitimate exercise of the police power. See Brett v. Building Comm'r of Brookline, 250 Mass. 73 , 77-78 (1924). "[W]hile property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking .... [A] strong public desire to improve the public condition is not enough to warrant achieving the desire by a shorter cut than the constitutional way of paying for the change .... [T]his is a question of degree ...." Aronson v. Sharon, supra at 604, quoting Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 415-416 (1922). See Commissioner of Natural Resources v. S. Volpe & Co., 349 Mass. 104 , 107-111 (1965). The regulation constitutes a taking only if it "deprives the [plaintiff's] land of all practical value to [her] or to anyone acquiring it, leaving them only with the burden of paying taxes on it." MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 641 (1970).

As appears from the quotation from MacNeil set forth above, the regulation constitutes a taking only if it deprives the land of all pracitical value. See Turnpike Realty Co. v. Dedham, 362 Mass. 221 (1972); MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 (1970); Barney & Carey Co. v. Milton, 324 Mass. 440 (1949); Loveguist v. Conservation Commission of Dennis, 379 Mass. 7 (1979). I do not reach the question, however, as to the validity of the ordinance as it impacts on the land of all the parties here in the light of my ruling on its facial invalidity.

The original plaintiffs requested this court to make certain findings of fact. Of these I grant Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 19, 20, 21 and deny Nos. 12 and 14-18 inclusive. They also requested certain rulings of law of which I grant Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 15 and 16 and deny Nos. 2, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 14.

Judgment accordingly.

WALTER BUSHMICK, JOHN W. BUCKLEY and JOHN E. MALONEY, Trustees; RICHARD L. PINKHAM, Intervener; ALBERT F. CURRAN, as Trustee, Intervener; and JOHN F. GILGUN, Intervener vs. CITY OF WOBURN.

WALTER BUSHMICK, JOHN W. BUCKLEY and JOHN E. MALONEY, Trustees; RICHARD L. PINKHAM, Intervener; ALBERT F. CURRAN, as Trustee, Intervener; and JOHN F. GILGUN, Intervener vs. CITY OF WOBURN.