LAURETTA M. LEBEL vs. MELLIN G. NELSON, et al.

LAURETTA M. LEBEL vs. MELLIN G. NELSON, et al.

MISC 105830

October 5, 1987

Essex, ss.

FENTON, J.

LAURETTA M. LEBEL vs. MELLIN G. NELSON, et al.

LAURETTA M. LEBEL vs. MELLIN G. NELSON, et al.

FENTON, J.

This case involves a claim of adverse possession of land located along the Danvers River in Danvers, Massachusetts. The plaintiff, Lauretta M. Lebel, is the record owner of two contiguous parcels of land and a house together known as Rear, 33 Bates Street, Danvers. She has lived in the house since 1943. In her amended complaint, the plaintiff alleges that she and her family have used and possessed an area (hereinafter "the disputed area") lying to the south and west of her deeded lot, and that said use and possession was open, notorious, actual, exclusive, hostile, adverse, continuous and uninterrupted for over twenty years. The plaintiff seeks a declaration by this court under G.L. c. 231A that she has acquired title to the disputed area by adverse possession. The defendant, Mellin G. Nelson, is the record owner of a parcel of land that encompasses the disputed area. In his answer, the defendant denies the plaintiff's key allegations and requests that the court declare him to be the undisputed owner of the disputed area. The U.S. Small Business Administration, a mortgagee of the defendant's parcel, was joined as a defendant and was duly served but did not appear.

A trial was held extending over ten days at which a stenographer was sworn to take and transcribe the testimony. Fifteen witnesses testified, and the court took two views of the locus in the presence of counsel. All sixty-seven exhibits introduced into evidence are hereby incorporated into this decision for the purpose of any appeal. Based on all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

1. The plaintiff, Lauretta M. Lebel, in the record owner of two contiguous parcels of land in Danvers, Massachusetts. The larger of the two parcels (hereinafter the "main parcel") was conveyed to the plaintiff and her late husband by a deed from Thomas A. and Frances J. O'Neil dated September 30, 1943, recorded with the Essex South District Registry of Deeds in Book 3349 at Page 137. A smaller adjacent parcel was conveyed to the plaintiff and her late husband by a deed from Elsie M. Rix dated October 16, 1944, recorded with said Registry of Deeds in Book 3385 at Page 555. A dwelling exists on the main parcel in which the plaintiff has resided with various members of her family since 1943. The land and dwelling together are known as Rear, 33 Bates Street.

2. The defendant, Mellin G. Nelson, is the record owner of two contiguous parcels of land in Danvers, Massachusetts, one of which is contiguous with the plaintiff's main parcel. The defendant acquired an undivided one-half interest his land by a deed from the Beverly National Bank, Trustee, dated January 21, 1970, recorded with the Essex South District Registry of Deeds in Book 5663 at Page 100. He acquired the remaining one-half interest in the land by a deed from Richard H. Brady dated May 24, 1971, recorded with said Registry of Deeds in Book 6064 at Page 6. The defendant operates on his land (but not in the disputed area) a business known as Danvers Yacht & Marina, Inc., whose address is 128R Water Street, Danvers.

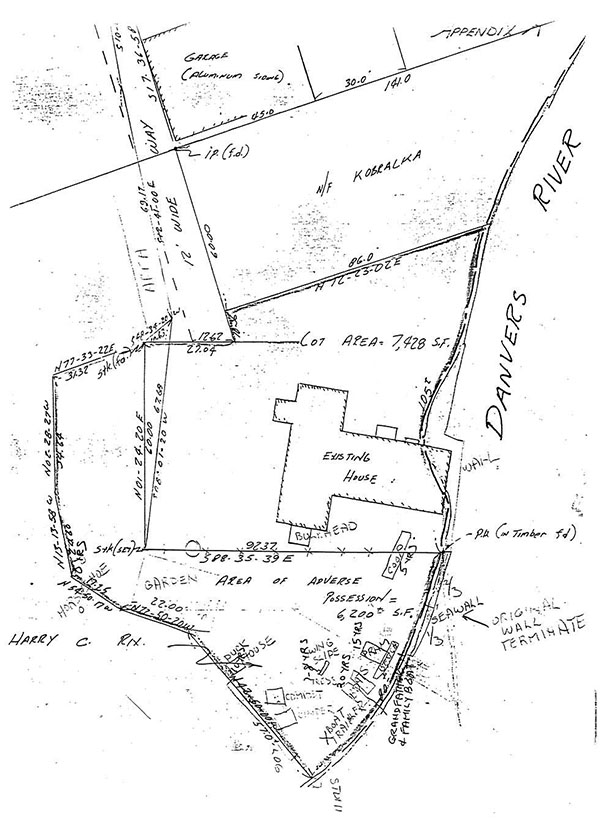

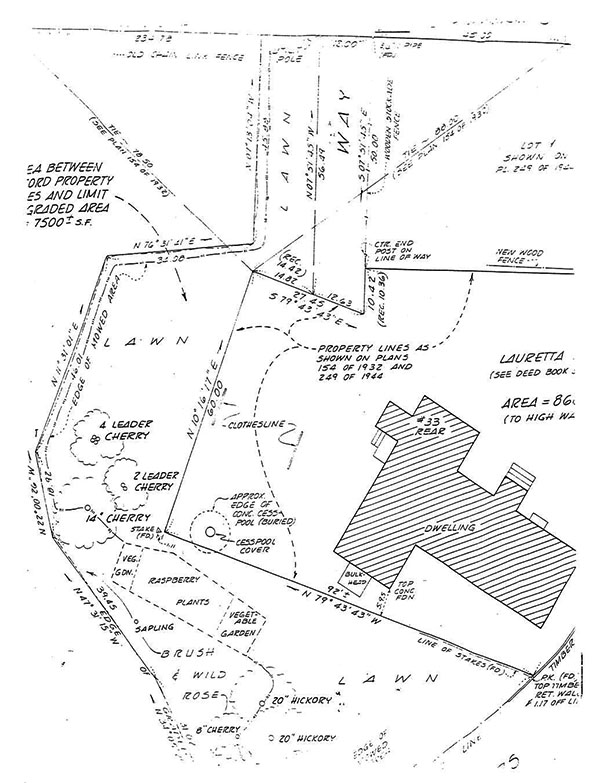

3. Unsure of the boundaries of her land, the plaintiff and her family began in 1944 to conduct various activities in an area lying to the south and west of her main parcel, record title to which area is now in the defendant. The disputed area is shown on a plan entitled "Plan of Land Owned by Lauretta Lebel in Danvers, Mass." by Kenneth J. Bouffard Associates dated July 3, 1983, which plan is Trial Exhibit 56 and which has been reproduced in relevant part and attached hereto as Appendix A. [Note 1] The disputed area is the area in heavy outline, exclusive of the plaintiff's deeded parcels. Additionally, the plaintiff claims a rectangular area outside the heavy outline to the north of the northwest corner of her main parcel, which area is marked "AREA" on Appendix A and is adjacent to a 12 foot wide right-of-way. The dimensions of this additional claimed area are shown on Trial Exhibit 41, which has been reproduced in relevant part and attached hereto as Appendix B. The area is marked "LAWN" and is bounded on the easterly side by the 12 foot wide right-of-way and on the westerly side by a broken line. The entire claimed area contains approximately 6,900 square feet.

4. The plaintiff and her family have conducted the following activities, among others, within the disputed area:

a) cleared land of brush in 1944 and maintained lawn from 1944 to time of trial;

b) planted garden in 1945 and maintained same to time of trial, though number and variety of plantings diminished in early 1970's;

c) planted rose bushes southeast of garden in mid-1940's and maintained same until late 1960's;

d) maintained and used compost pile from 1945 to time of trial;

e) maintained and regularly used cinder pile from 1945 or 1946 to late 1960's, frequency of use declining since then but continuing at time of trial;

f) constructed wooden seawall in 1945 or 1946 and extended same during early 1960's, part of which extension was damaged in 1978, remainder of wall intact at time of trial;

g) constructed horseshoe court around 1953 and used until mid-1960's, one of whose poles remained in ground at time of trial;

h) constructed children's swing and slide in mid-1940's and maintained until mid-1950's;

i) constructed "duck house" in late 1940's used initially as duck housing, then for play, and finally for storage until its removal in 1970 or 1971;

j) constructed chicken coop in mid-1940's and used until removal in late 1940's;

k) used trunk of fallen tree as bench from mid-1940's through at least 1960, trunk remaining in position at time of trial;

l) stored boats and related equipment during boating off-season from mid-1940's, two boats and trailer remaining at time of trial;

m) held family picnics of from 15 to 40 people, which picnics involved typical gastronomic and recreational activities, from mid-1940's until late 1960's;

n) used portion of lawn for parking and turning around of cars from 1946 to time of trial.

5. While most of the objects and structures mentioned in the preceding paragraph remained in the disputed area year-round, the human activities described were primarily seasonal in nature, taking place during summer and the warmer months of spring and fall.

6. The plaintiff and her family also made occasional use of the Danvers River and its tidal flats for activities such as swimming, boating, and harvesting clams, although no evidence was adduced as to the exclusivity or duration of such use, nor as to the state of title to the flats. [Note 2]

7. At no time did the plaintiff or any member of her family receive permission from the defendant or any of his predecessors in title to enter upon and use any portion of the disputed area.

8. At no time did the defendant or his predecessors in title object to the activities of the plaintiff and her family within the disputed area until April, 1982, after the initiation of this lawsuit, when the defendant requested by letter that the plaintiff remove stakes that she caused to be placed in the disputed area.

9. The plaintiff used and possessed the disputed area exclusively, as an average owner would, from 1944 until at least 1976, when at the defendant's behest a land surveyor entered the disputed area and placed stakes in the ground along the common border of the plaintiff's and defendant's deeded lots.

10. In the early 1970's, upon the death of her husband, the plaintiff became less vigilant in caring for portions of the disputed area more distant from her house. The southernmost portion became overgrown with brush and brambles and remained so until approximately 1976, when the plaintiff began gradually to clear the area. By the late 1970's the disputed area again appeared as it did during the period from the mid-1940's to the late 1960's.

11. Sometime in 1970, during a survey of the disputed area, the defendant determined that the plaintiff was "overmowing" her lawn by approximately 15 to 20 feet to the west and 10 feet to the south of her deeded lot lines.

12. In 1978, the plaintiff offered to purchase from the defendant a strip of land to the west of the 12 foot right of way so the plaintiff could legally prevent neighbors from dumping trash there. The plaintiff's offer was refused.

13. In February, 1981, the Army Corps of Engineers published notice of a proposed expansion of Danvers Yacht & Marina. Shortly thereafter, the plaintiff asked the defendant to explain to her the area of the proposed expansion. Following the defendant's explanation, the plaintiff offered to purchase some land to the south and west of her deeded lot, which offer was refused.

14. In February, 1982, the plaintiff filed a complaint in the Land Court claiming title to the disputed area by adverse possession.

Title by adverse possession can be acquired only by proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949); Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961); Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). The plaintiff's burden of proof runs to each of the necessary elements, and if anyone is left in doubt, the plaintiff cannot prevail. See Gadreault v. Hillman, 317 Mass. 656 , 661 (1945); Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949); Mendonca v. Cities Service Oil Co., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968).

In the instant case I have found, notwithstanding hearsay testimony of record to the contrary, that the plaintiff's use of the disputed area was nonpermissive (Finding No. 6). I have also found that the plaintiff made actual use of the disputed area in a variety of ways (Finding No. 4).

As to the requirement that the claimant's possession be open and notorious, it has long been held that proof of the owner's actual knowledge is unnecessary. See Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 217-218 (1955). In Foot, the Supreme Judicial Court adopted the position of the American Law of Property that "[t]o be open the use must be made without attempted concealment. To be notorious it must be known to some who might reasonably be expected to communicate their knowledge to the owner if he maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over his premises." 333 Mass. at 218 (quoting 2 Am. Law of Property § 8.56 (1952)). The purpose of this requirement is to "secure to the owner a fair chance of protecting himself." Id.

Here, the plaintiff and her family put the disputed area to a wide variety of uses for over thirty years, never attempting to conceal their activities. These activities were of such a nature that the defendant and his predecessors in title, upon any reasonable inspection of the area, could have discovered the adverse use. In fact, in deposition testimony he corroborated at trial, the defendant indicated that during a 1970 survey of the area he determined that the plaintiff was "overmowing" her lawn by approximately 15 to 20 feet to the west and 10 feet to the south of her deeded lot lines (see Finding No. 10). The defendant did not object to this apparent encroachment at the time, and did not raise the matter during his subsequent meetings with the plaintiff.

The defendant makes much of his claim that the disputed area was not always visible from that portion of his land where the marina buildings are located. Even if proven, however, such a claim is not dispositive of the "open and notorious" element under the rationale of Foot v. Bauman, supra. I find that the plaintiff's myriad activities in the disputed area, taken as a whole, were open and notorious at all times relevant to this proceeding.

I have already found that the plaintiff's use and possession of the disputed area was exclusive (see Finding No. 8). This finding is not inconsistent with the testimony of two witnesses who claimed to have played in the disputed area occasionally as children, especially in light of one's further testimony that he was once shooed away by the plaintiff.

The plaintiff also must satisfy the court that her possession was adverse, an element sometimes referred to as the "hostility" requirement.

In days gone by our courts employed a subjective test, inquiring whether a possessor's acts of dominion were committed with the intent to claim rightful ownership of the land in dispute. Since Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 (1958), however, the rule in this Commonwealth has been unequivocal that "the uncommunicated mental attitude of the possessor is irrelevant where his acts import an adverse character to his holding. . . ." Id. at 334. As the purpose of the hostility requirement is to ensure that the true owner had a fair opportunity to discover the adverse use, "acts alone . . . may be sufficient to put the true owner on notice of the nonpermissive use." Id.

Here, the plaintiff's activities within the disputed area commenced in 1944, and were ongoing at the time the trial began. Although the defendant did not acquire an interest in the disputed area until 1970, he is nonetheless chargeable with the failure of his predecessor(s) in title to take any action with respect to the plaintiff's use and enjoyment of the area. As noted above, the defendant was aware of some encroachment by the plaintiff as early as 1970; however, even if the plaintiff was no longer in possession of the disputed area at that time, she still could maintain an action against the defendant based on more than 20 years of adverse use prior to the defendant's acquisition of record title to the area. See 4 Tiffany on Real Property § 1177 (3d ed. 1939). In any event, I find that the plaintiff's acts within the disputed area since 1944 were sufficient to put the true owners, including the defendant, on notice of the nonpermissive use, and thus were adverse as that term has been elucidated by our case law. [Note 3]

Finally, the plaintiff must prove that her nonpermissive, actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse use was sustained without material interruption for over twenty years. It has been held that the nature and extent of occupancy required to establish title by adverse possession varies with the character of the land, the purposes for which the land is adapted, and the uses to which the land has been put. LaChance v. Rubashe, 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938). In LaChance, the plaintiff sued to enjoin the defendant from trespassing on a strip of land to which the plaintiff held record title. 301 Mass. at 488. The defendant claimed title to the strip by adverse possession. Id. at 489. Although no single act of dominion by the defendant or his predecessor in title was sustained on the strip for more than twenty years, the court affirmed a lower court decree in favor of the defendant, accepting the defendant's contention that the overlapping acts carried out on the strip could be "tacked together" to meet the statutory period. Id. at 490. The court stated that the acts of the defendant and his predecessor "constituted such a control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership." Id. at 491 and cases cited. A more recent case held that adverse possession may lie where the use and enjoyment of the property is "as the average owner of similar property would use and enjoy it, so that people residing in the neighborhood would be justified in regarding the possessor as exercising the exclusive dominion and control incident to ownership. . . ." Shaw v. Solari, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 156-157 (1979) (quoting 3 Am. Law of Property§ 15.3 (1952)).

Here, although certain of the plaintiff's activities within the disputed area, such as establishing and maintaining a lawn, garden, and seawall, were sustained for the full statutory period, numerous others were not. The plaintiff need not prove continuous use and possession of each square inch of the disputed area, however; only that the totality of her use and possession was as an average owner of similar property would use and enjoy it. Likewise, the plaintiff's claim is not jeopardized by the fact that her use of the disputed area was primarily seasonal in nature. Considering the often inhospitable nature of winter in New England, it is certainly natural that the use of land in general, and of riparian land in particular, is concentrated in the warmer months. In any event, the plaintiff maintained several structures and other objects in the disputed area on a year-round basis (see Finding No. 4). Accordingly, I find that the plaintiff's nonpermissive, actual, open, notorious, exclusive, and adverse use and possession of the disputed area, beginning in 1944, was sustained continuously for over twenty years, and that she has thus established title to the disputed area by adverse possession.

The court has found the facts in detail and set forth the applicable law in its decision, and therefore declines to rule individually on the parties' numerous requests for findings and rulings.

Judgment accordingly.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Appendix A bears extraneous markings which were added to the plan to assist the court when the plan was being used as a chalk. The plan with the markings thereon was later admitted into evidence without objection and is appended hereto merely to define the perimeter of the disputed area.

[Note 2] It is a longstanding rule in the Commonwealth that, unless separated by the conveyance of one without the other, title to the flats lying between the high and low water marks, limited to a width of 100 rods as measured from the high water mark, follows that of the upland. See Drake v. Curtis, 55 Mass. 395 , 412-413 (1848); Porter v. Sullivan, 73 Mass. 441 , 445 (1856). Such title is subject to the rights of the public to fish, fowl, boat, swim, and float in and upon the waters which cover the flats from one low tide to the next, with the exception that the public has no right to use for bathing purposes that part of the beach or shore above the low water mark where the distance to the high water mark does not exceed one hundred rods, whether covered with water or not. See Butler v. Attorney General, 195 Mass. 79 , 83-84 (1907); Opinion of Justices, 365 Mass. 681 , 685-686 (1974). In the instant case, however, neither the plaintiff's nor the defendant's pleadings contain a claim of title to the adjacent flats and thus the issue is beyond the purview of the court at this time.

[Note 3] Although uncontradicted evidence showed that the plaintiff, on at least one occasion, offered to purchase part of the disputed area from the defendant, this fact alone does not amount to an admission by the plaintiff that she was not the rightful owner of the area. With nothing more, an offer to purchase may merely indicate a party's willingness to pay something for disputed land to avoid litigation. See Warren v. Bowdran, 156 Mass. 280 , 283 (1892). See also Hurley v. Sarkisian, Land Court Misc. Case No. 91386 at 14 (April 6, 1983) (claimant's offer to purchase disputed property does not require finding that possession not adverse).