CHESLEY R. TAYLOR vs. JAMES M. RYAN and GERALDINE ROWLEY RYAN

CHESLEY R. TAYLOR vs. JAMES M. RYAN and GERALDINE ROWLEY RYAN

MISC 108718

December 1, 1987

Essex, ss.

SULLIVAN, C. J.

CHESLEY R. TAYLOR vs. JAMES M. RYAN and GERALDINE ROWLEY RYAN

CHESLEY R. TAYLOR vs. JAMES M. RYAN and GERALDINE ROWLEY RYAN

SULLIVAN, C. J.

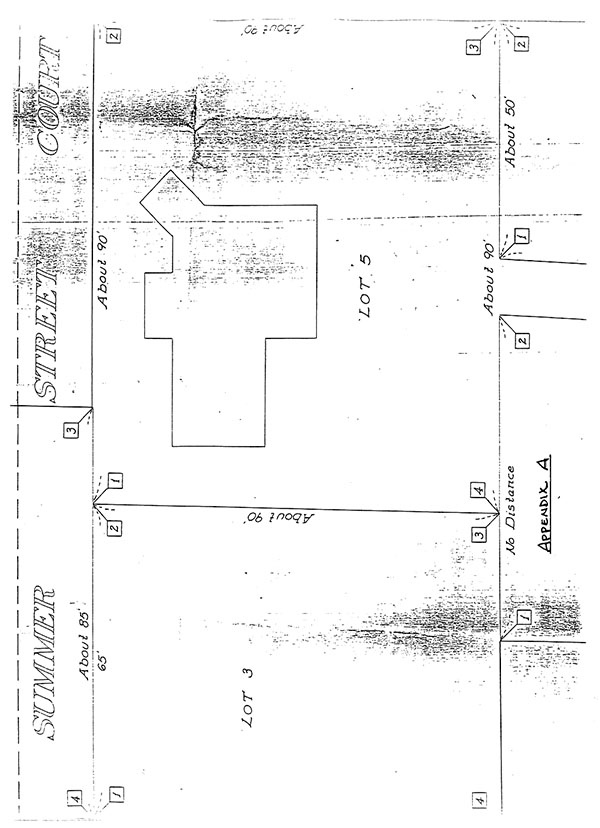

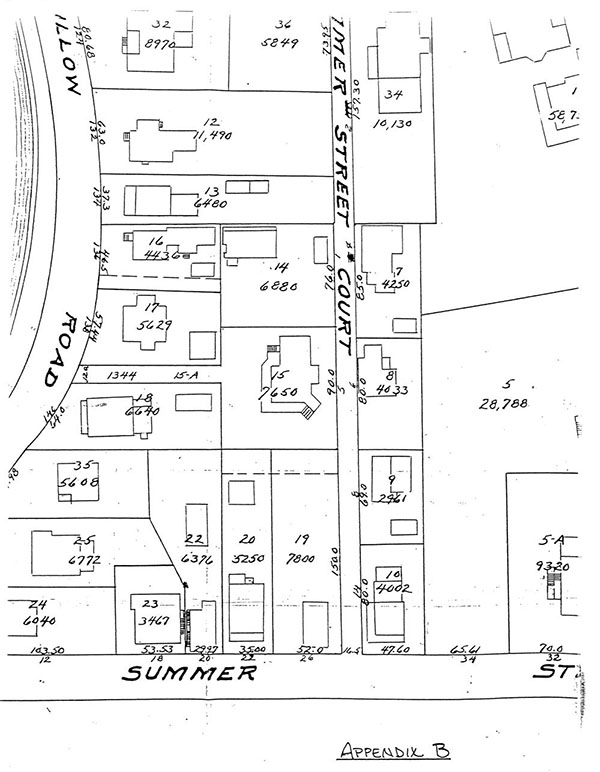

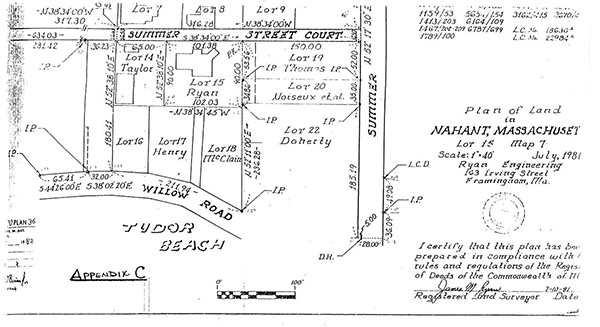

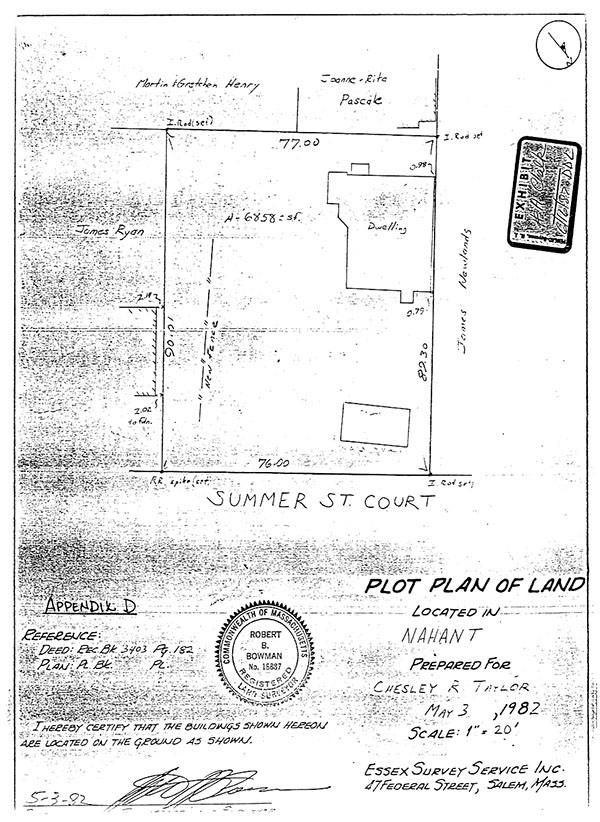

Chesley R. Taylor of Nahant, in the County of Essex, brings this complaint for continuing trespass and injunctive and declaratory relief to determine the rights in a strip of land approximately eleven (11) feet in width situated between the lands admittedly of the plaintiff and of the defendants James M. Ryan and Geraldine Rowley Ryan, also both of said Nahant, and running between Summer Street Court and land of third parties. The plaintiff claims to have acquired title to the strip by adverse possession, and the defendants claim title by a construction of the deeds in their record chain of title. The defendants further deny that the plaintiff's use of the area was open, notorious and adverse. There is attached hereto a series of plans which highlight the problem. Appendix A is a copy of a portion of Chalk B which shows the plaintiff's land as Lot 3 with 65 feet on Summer Street Court and the defendants' land as Lot 5 with a frontage of "About 90'"; Appendix B is a portion of Exhibit No. 8C, which is an assessors' map for locus on which the plaintiff's land is shown as having a frontage of 76 feet and that of the defendants 90 feet; Appendix C is a copy of a portion of Exhibit No. 6, a plan prepared by the defendant James M. Ryan, a registered land surveyor, which shows the plaintiff's land as having a frontage on Summer Street Court of 65 feet and the defendants' land with a frontage of 101.38 feet; and finally Appendix D is a copy of Chalk A entitled "Plot Plan of Land Located in Nahant Prepared For Chesley R. Taylor" dated May 3, 1982 by Essex Survey Service, Inc.

In April of 1982, two years after the defendants took title to the lot abutting that of the plaintiff on the east, the vegetation in the area of the common bound was removed by the defendant, James M. Ryan, who thereafter constructed a fence along a line he believed to be the common boundary. The fence partially obstructed the plaintiff's driveway. This activity prompted protests by the plaintiff who asserted title to the area and subsequently filed this action. A hearing was held on the request for injunctive relief, and a preliminary injunction issued enjoining any activity by either party in the disputed eleven foot wide strip until further order of Court and providing for passage by the plaintiff on foot or by vehicle over the area of his existing driveway.

A trial was held on June 16 and August 25, 1987 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. Eleven multi-part exhibits were introduced into evidence, together with the two chalks to which reference is made above. Witnesses who testified for the plaintiff at the trial were Chesley R. Taylor, his wife, Marian Taylor, the plaintiff's daughter, Sally A. Taylor Lee, and the plaintiff's son, Chesley R. Taylor, Jr. Witnesses for the defendants were James M. Ryan, Evelyn McLean, Phyllis Peters, Harriet Steeves and Suzanne Heidebriedt. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. At the close of the plaintiff's case the defendants moved in effect for a directed finding on the ground that the evidence of adverse possession was insufficient, specifically as to the requisite twenty year period. After consideration, the motion was denied in open Court.

This controversy has its roots in the fact that the measurements shown on the early subdivision of the area gives the combined frontage of the lots owned by the parties as about 155 feet, whereas the recent survey prepared by the defendant James M. Ryan finds a total frontage of more than 166 feet on the ground. Cf. Mercurio v. Smith, 24 Mass. App. Ct. 329 (1987). It is the proper allocation of the eleven feet in dispute which is at issue here. The plaintiff claims that the Taylor family has used the disputed area for nearly eighty years, originally through actions of the plaintiff's father and family and thereafter through those of the plaintiff and his family.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

1. The plaintiff is a man 79 years old. The plaintiff grew up in his father's house on the locus where he lived from the time of his birth in 1908 until the early 1940's with other family members, including his two brothers. The plaintiff's father, J. Frank Taylor, had acquired title to the premises known as 1 Summer Street Court in said Nahant from Ella R. Burford by deed dated June 28, 1905 and recorded with Essex South District Deeds (to which all recording references refer) Book 1789, Page 100 (Exhibit No. 2). The description of the premises set forth in said deed bounded the premises "Northeasterly by land of Hortense Luscomb and Summer Street Court sixty-five (65) feet and southeasterly by land of Lydia L. and Susie Luscomb, ninety (90) feet..." There are no other distances set forth in this deed, but it contains the general caveat "Be (sic) the same measurements more or less..." The plaintiff remembers that when he was a child, there was a row of bushes running from the "L" of the Ryans' house to the back of the lots of the plaintiff and defendants where a then neighbor, Martin Henry, had a fence. Prior to the removal of the row of bushes by Mr. Ryan, it had grown to about 20 feet in height, was 3 feet wide and impenetrable except for one opening which the Taylor family kept blocked by a bicycle. The plaintiff was uncertain who had planted the bushes, but it was his belief that this was done by a predecessor in title of the defendants. The bushes left the disputed eleven feet on the Taylor side, and the family proceeded to use this area for roughly 70 years thereafter. The plaintiff testified that he remembered during World War I his parents had a victory garden in the area now in dispute.

2. When Mr. Taylor was married, he and his wife originally lived in another location for a year or two, but in 1943 Mr. and Mrs. Taylor moved into his father's home on the locus where they raised a family of five children, two of whom testified at the trial. Mr. Taylor's father died on September 24, 1944 intestate, leaving as his only heirs at law and next of kin his three sons (Exhibit No. 3). Thereafter, by deed dated May 2, 1945 and duly recorded in Book 3403, Page 182 (Exhibit No. 1), the plaintiff acquired title to 1 Summer Street Court from his brothers, Fred B. Taylor and F. Kenneth Taylor. The description in the deed follows that in the chain of title and as in the deed to the plaintiff's father gives a frontage of sixty-five (65) feet on Summer Street Court, bounds southeasterly by land now of the defendants ninety (90) feet and by two other courses, the lengths of which are not set forth.

3. As already stated the plaintiff and his wife have lived at 1 Summer Street Court since 1943. [Note 1] During the years which the plaintiff occupied the property first under his father's ownership and thereafter as the record owner by virtue of the deed from his brothers, he and family members used the land which is situated on the northwest side of the row of bushes as their own. Over the years, there originally were two Baldwin apple trees in the yard, at the base of which there was a strawberry patch and a grapevine. One of the apple trees was cut down by Mr. Taylor to make room for a vegetable garden in the area which was discontinued in 1977 due to his ill health. Six lilac bushes were planted along the row of bushes by the Taylors, and they from time to time trimmed their side of the row of bushes whenever it appeared overgrown. Chesley R. Taylor, Jr., who lived with his parents from 1948 to 1973 testified that he had played baseball in the disputed area with friends, had planted tulips near a forsythia and had stored his lobster boat and lobster pots in the area. The testimony of these witnesses appears credible since it is logical that when any kind of artificial boundary is erected which runs along most of a line between two properties, the area left between the bushes or fence or other dividing structure will be used by those upon whose side the open land is found, whether the true boundary or not. In the present case, it appears that the entrance to the driveway leading into the plaintiff's property was situated at the easterly corner of the property adjacent to the Ryans' land and that after the driveway entered from the street, it swung in a northerly direction to the garage. The driveway met the bushes which ran from the southwesterly side of the driveway southwesterly to the rear of both properties.

4. It is the dimension of the frontage of the lots owned by the parties which generates the disputed eleven foot wide strip between the two lots. The above-mentioned deeds in the plaintiff's back title, that of Ella R. Burford and that of the plaintiff's brothers, describe the plaintiff's lot as bounded by Summer Street Court for a distance of sixty-five (65) feet. The deed of Thomas C. Solone and Lisa S. Solone to the defendants describes their lot as bounded by Summer Street Court for a distance of "about 90 feet". The plaintiff claims an additional eleven feet of frontage for a total of seventy-six (76) feet by adverse possession. The defendants deny this claim and assert, in reliance upon the survey done by the defendant, James M. Ryan, entitled "Plan of Land in Nahant, Massachusetts - Lot 15 - Map 7", dated July 1981 and recorded as Plan 36 in Plan Book 170 (Exhibit No. 6), that their frontage in fact consists of 101. 38 feet. A plan of the plaintiff's lot entitled "Plot Plan of Land Located in Nahant - Prepared for Chesley R. Taylor" dated May 3, 1982 by Essex Survey Service, Inc. and marked at trial as Chalk A in the absence of testimony by the surveyor, Robert B. Bowman, shows seventy-six (76) feet of frontage set off between an iron rod (set) and a R.R. spike (set).

5. The Nahant Assessor's appraisal card for the tax year 1961 shows the plaintiff's lot (Lot 14, Map 7) as having a total area of 6,880 square feet and 76 feet of frontage (Exhibit No. 9B). From 1981 to 1986 these same records and the ownership cards (Exhibit No. 9A) show Lot-14 as having a total area of 6,844 square feet. The 1981 appraisal card (Exhibit No. 9B) bears a hand-written notation to the effect that an error in square footage has been corrected. The Assessor's map 7 for the years 1924, 1963 and 1970 (Exhibit Nos. 8A-8C) shows the total area of Lot. 14 as 6,880 square feet and the frontage as 76 feet. Five sets of the Assessor's valuation sheets were introduced into evidence for ten year intervals from 1947 to 1987 (Exhibit Nos. 11A-11E). The area of the plaintiff's lot shows as 6,880 square feet from 1947 to 1977 and as 6,844 square feet for 1987. In neither the case of Lot 14 or Lot 15 are the area figures material unless they reflect a change in frontage, one element in the computation of the square feet. This has not been shown to be the case.

6. The Nahant Assessor's ownership cards for the defendants' lot (Lot 15) for the period from 1958 to 1973 (Exhibit No. 10A) show Lot 15 as having a total area of 7,650 square feet. Prior to 1973 these cards show a second parcel known as Lot 15A, described as a right of way having an area of 1,350 square feet for a total area of 9,000 square feet for the combination of Lots 15 and 15A (Exhibit No. 10A). The ownership card for 1971 bears a hand-written notation that Lot 15A, was sold in 1973 to Peterson and shows Lot 15 as having 8,100 square feet after the sale. The figures for subsequent years reflect an increase in area of 450 square feet with which we need not be concerned. The only appraisal card showing a frontage figure for Lot 15 is fer the period from 1958 to 1979, and the frontage is given as 90 feet. The valuation sheets (Exhibit Nos. 11A-11E) show the defendants' lot as having an area of 7,650 square feet for 1947 and 1957, as 9,000 square feet in 1967 and as 8,100 square feet for 1977 and 1987. The Assessor's map 7 for the years 1924, 1963 and 1970 shows Lot 15 as having an area of 7,650 square feet with frontage of 90 feet.

7. Mr. Ryan testified at length as to his methodology in making the survey from which he drew up his plan showing his lot as having 101.38 feet of frontage which he recorded and which was admitted as Exhibit No. 6. During the course of his search of the records at the Registry of Deeds, he found a series of deeds dated 1896 by William Luscomb, the common grantor of both the Taylor and Ryan lots (Exhibit Nos. 7A-7E). Mr. Ryan drew up a plan of the 1896 division which was marked Chalk B. The Luscomb division appears to have been the source of the lack of exact dimensions for the lots along Summer Street Court as certain lots conveyed had no dimensions and others were given only partial dimensions.

8. Three witnesses from the neighborhood, one of whom had been involved in a previous dispute over use of her property, contradicted the evidence of the plaintiff's witnesses, but I have found the latter to be credible. Mr. Ryan's testimony regarding some of the discarded items he found and removed from his own lot and the disputed area appears to corroborate, at least in part, the uses described by the Taylor family; bicycles, bushels of rotten apples and lobster traps. Mr. Ryan relies in part upon this testimony to rebut the plaintiff's evidence of adverse use since at the time of his purchase in 1980 he found the disputed area weedy and overgrown, the bushes untrimmed and various long-discarded items left lying about.

This Court has frequently set forth the law applicable to the acquisition of title by adverse possession as it is found in decisions of the Supreme Judicial Court and the Appeals Court. The plaintiff must show an uninterrupted use of the premises in question which is open, notorious, exclusive, continuous and adverse for a period of at least twenty years. E.g., Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961); Boston Seaman's Friend Society, Inc. v. Rifkin Management, Inc., 19 Mass. App. Ct. 248 , 251 (1979) rev. den. 394 Mass. 1101 (1985). The burden is on the party claiming title by adverse possession to establish each of these familiar elements, but once they have been shown, a lessening of the use or even its cessation after the twenty year period has run does not negate the title thus previously acquired. See Holmes v. Johnson, 324 Mass. 450 , 453 (1949); Daley v. Daley, 300 Mass. 17 , 21 (1938); 4 Tiffany, The Law of Real Property, s. 1172 (3d. ed. 1975). The focus then shifts to a question of abandonment which is not shown on the facts which I have found. The defendants argue that the plaintiff has not shown that his use of the disputed area was notorious since none of the neighbors who testified recalled any member of the plaintiff's family gardening, playing ball or otherwise using the area as alleged. It is established that to meet the requirement of notorious use the claimant's occupation must be so open and apparent as to communicate to the true owner, or other observers likely to report such activities to him, that another is exercising possession adverse to that of the holder of the record title. LaChance v. First National Bank and Trust of Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488 , 491-492 (1938); Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955). Actual knowledge is not necessary, only the opportunity to learn of the adverse possession in the exercise of due diligence. In Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959), the Supreme Judicial Court reviewed the doctrine and concluded that the purpose of the various requirements of adverse possession is to put the true owner "on notice of the hostile activity of the possession so that he, the owner, may have an opportunity to take steps to vindicate his rights by legal action." There was such opportunity in the present case where a period of nearly eighty years was involved.

It seems apparent from the evidence that the predecessors in title of the defendants indeed were aware of the existence of the barrier of bushes and easily could have informed themselves of the use being made of the strip between the natural fence and the true property line. The continuance of such a barrier where access is continuously denied to the owner of record and the land is available only for the exclusive nonpermissive use of the claimant is sufficient to show the elements for the acquisition of title. See Shaw v. Solari, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 156 (1979). Compare Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 260-263 (1964).

While it may be that enclosure or fencing alone is enough to establish adverse possession, it is significant here that the assessors' records also accord with use which the plaintiff has made in that they show the plaintiff's frontage as being 76 feet. In addition, the evidence which the plaintiff introduced and which I have accepted shows many acts over a very lengthy period of time which are illustrative of the exercise of dominion and exclusive possession. There was no evidence that any party in the defendants' chain of title ever used the eleven feet in question. The use for gardens, plants, trees and children's games by the plaintiff, his predecessors in title and his family members is buttressed also by the placement of a portion of the plaintiff's driveway in the disputed area where it is clear no one under whom the defendants claim made any use of the way. If the parties were in disagreement over an area where there was not intense residential use, it is possible that the result might be different. See Cowden v. Cutting, 339 Mass. 164 , 168 (1959); McDonough v. Everett, 237 Mass. 378 , 384 (1921); Parker v. Parker, 1 Allen 245 (1861).

Here, however, the density of lots in the area, the barrier to access from the defendants' property to the disputed strip presented by the bushes, and the presence of the driveway used only by the plaintiff support the plaintiff's claim to title acquired by adverse possession. Accordingly, I find and rule that on all the evidence the plaintiff has proved by a preponderance of the evidence that he has acquired title to the strip of land eleven feet in width by the exercise of adverse possession. The result which I have reached disposes of the defendants' argument that the plaintiff's claim was frivolous and entitles them to damages pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 231, §6F. I also find and rule that there was no evidence to support the defenses of laches and unclean hands. The Judgment which is to be entered will provide that the defendants, their agents, servants and employees are restrained from entering upon the strip in dispute, but will reserve to the defendants a right, if necessary, to enter upon such part thereof as may be equired to make any repairs or to paint the northwesterly wall of said building.

Judgment accordingly.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

exhibit 4

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The defendants comment in their brief on the failure of the plaintiff to have any non-family members testify as to adverse possession and point also to the neighbors who either denied or did not remember the activities for a determination as to the credibility of the witnesses; however, this is a province of the Court, and is reflected in my findings.