NANCY MILLER, et al. vs. MERWIN E. DURGIN, et al.

NANCY MILLER, et al. vs. MERWIN E. DURGIN, et al.

MISC 94,337

December 31, 1987

Norfolk, ss.

QUIRICO, J.

NANCY MILLER, et al. vs. MERWIN E. DURGIN, et al.

NANCY MILLER, et al. vs. MERWIN E. DURGIN, et al.

QUIRICO, J.

In this action the plaintiffs allege that they are the owners of several inland lots appurtenant to which there are easements giving the plaintiffs, as the owners of these lots, the right of access to the beach at the ocean front of lots owned bv the defendants, and the right to use the ocean front beach in common with the defendants and the owners of other lots which were laid out as the same general development. They allege further that the defendants have wrongfully interfered with or prevented the plaintiffs in their exercise of those easement rights. The plaintiffs seek injunctive relief against the defendants, some of whom have in turn made counterclaims against the plaintiffs.

1. On September 15, 1870, Leuther Belcher, sometimes referred to as "Luther Belcher," and in this decision referred to as "Belcher," purchased a parcel of land in Quincy, by two deeds which described the land conveyed as follows:

". . . a certain lot of land being partly of upland and partly saltmarsh, containing twenty-three acres, more or less, situated in said Quincy, at a place called Rock Island and bounded as follows, viz., westerly on the crossway on saltmarsh of Seth Spear & on saltmarsh formerly of Thomas Adams, northerly on saltmarsh of sundry persons & on Rock Island Creek, so called, easterly and southerly on the saltwater or however otherwise bounded."

The deeds were recorded in Book 397, pages 259 and 260 of the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds, hereinafter referred to as the "Registry" or the "Registry of Deeds."

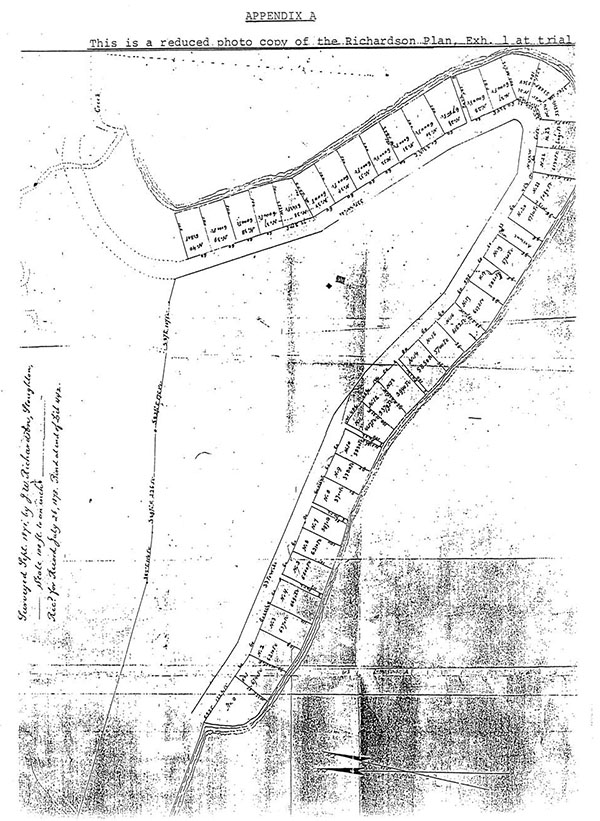

2. In September, 1871, Belcher caused a portion of Rock Island property to be surveyed and a subdivision plan of that portion to be made by one J. W. Richardson. That plan as recorded in the Registry of Deeds on July 26, 1873, at the end of Book 442, and is hereinafter referred to as the "Richardson Plan." A reduced photo copy of the Richardson Plan is marked "APPENDIX A" and is attached to and incorporated in this decision. (A full sized copy of the plan was introduced as Exh. 1 at the trial of this case).

3. Forty-one (41) lots, numbered zero (0) through forty (40) inclusive, were laid out on the Richardson Plan along the ocean side of Belcher's twenty-three (23) acre property. Each of the lots fronts on a street which is not named on the Richardson Plan but is named "Rock Island Road" in the 1896 revision of the plan to be described below. Most of the lots have a frontage of about sixty (60) feet on the street, with varying depths extending to the ocean in the rear. The lots owned by all of the defendants in this case are included on the Richardson Plan.

4. Although the Richardson Plan shows no inland lots, there were revisions of that plan which laid out many inland lots, including those of the plaintiffs who claim easement rights of access from their lots to the ocean front. That claim is based on the following areas which appear on the Richardson Plan:

(a) There are five (5) strips of land, each ten (10) feet wide and each extending from what later became Rock Island Road back down to the ocean front. Each of those strips is marked "Path" on the Richardson Plan, and they are located at the following places: between lots 4 and 5, between lots 7 and 8, between lots 10 and 11, between 13 and 14, and between lots 28 and 29.

(b) Well Avenue, 43 feet in width, located between lots 19 and 20.

Additional information concerning these strips of land and one additional similar strip is contained in a document marked "APPENDIX B" attached to and incorporated in this decision.

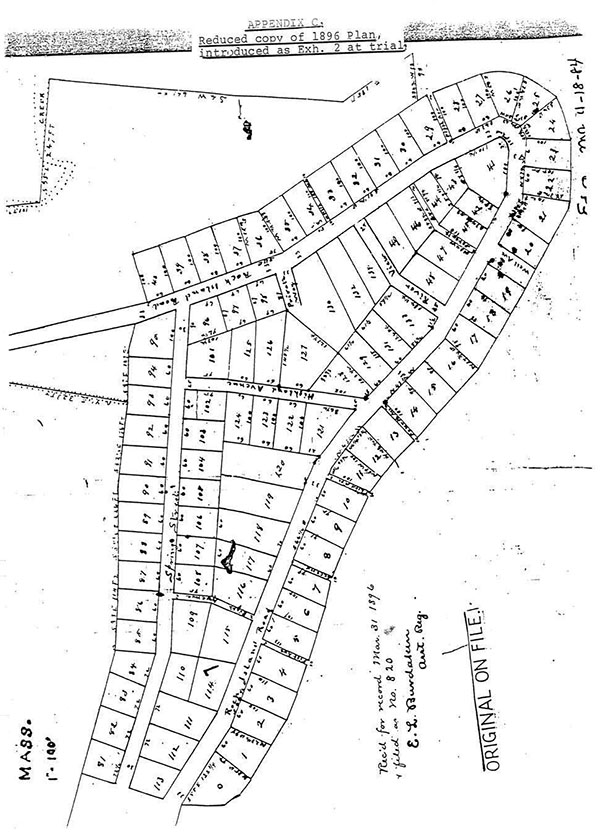

5. On March 31, 1896, a revision of the Richardson Plan was recorded in the Reqistry of Deeds and it is marked "filed [in the Reqistry] as No. 820." It will be referred to in this decision as the "1896 Plan." A reduced photo copy of the 1896 Plan is marked "APPENDIX C" and is attached to and incorporated in this decision. The 1896 Plan includes everything which was in the Richardson Plan and the following amendments or additions:

(a) The five strips, each 10 feet wide, and each identified as "Path" are now identified as "First Ave.", "Second Ave.", "'Third Ave.", "'Fourth Ave.", and "Fifth Ave." In addition, there is now on the 1896 Plan a strip of land 10 feet wide from Rock Island Road to the ocean, located between lots thirty-three (33) and thirty-four (34), and identified as "Sixth Ave." [For information on that strip, see APPENDIX C to this decision.]

(b) The unnamed road in the Richardson Plan is named "Rock Island Road" on the 1896 Plan.

(c) The 1896 Plan has new streets named Spring Street, Hiqhland Avenue, River View, and "Private Way," with lots laid out on all of them and also on the inland side of the oriqinal Rock Island Road.

(d) The 1896 Plan has two new strips which are ten (10) feet wide and which connect inland streets only. One is named "Seventh Ave.", between Rock Island Road another spot on the same road. The other is named "Eighth Avenue", between Rock Island Road and Spring Street.

(e) The new lots laid out on the 1896 Plan are numbered: 41 throuqh 49, 81 throuqh 98 and 101 throuqh 134. They are all inland lots.

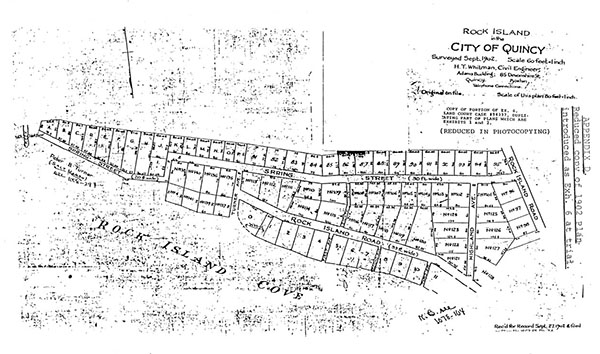

6. On September 27, 1902, a plan entitled "Plan of Land at Rock Island in the City of Quincy" was recorded in the Registry of Deeds and it is marked "Plan No. 1567 Pl. Bk. 34." It will be referred to in this decision as the "1902 Plan." It includes lots 0 through 11 as shown on the Richardson Plan, and lots 81 through 98 and lots 101 through 128 as shown on the 1896 Plan. In addition, it shows some lots A through P, 135 through 140, and a "No. 4'', all of which are located easterly of the easterly end of the 1896 Plan. The owners of these lots are not involved in this litigation. However, the 1902 Plan, a reduced photo copy of which is marked "APPENDIX D" is attached to and incorporated in this decision, shows a street entitled "TURNER AVE." which continues toward the ocean into an area which has been described as "Sandy Beach" where Lot "0" on the Richardson Plan borders the ocean. That area has been mentioned in the trial as one of the roads and areas by which persons living inland reached the beach or ocean front.

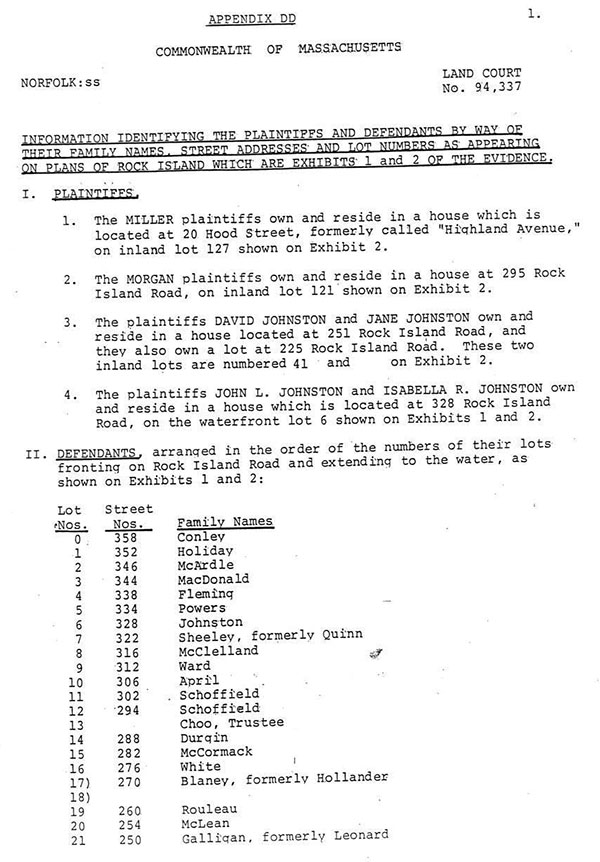

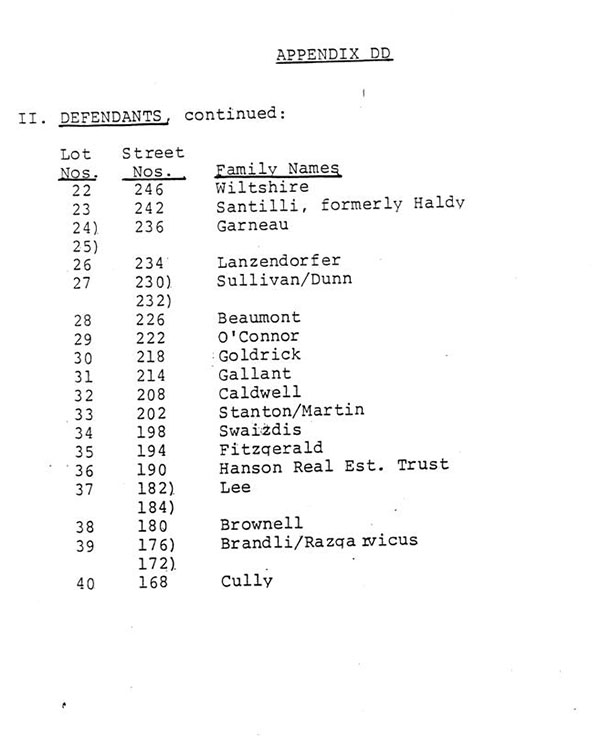

Now that all three subdivision plans of the Belcher property have been incorporated in this decision by way of reduced photo copies marked APPENDIX A, APPENDIX C, and APPENDIX D, it may be helpful to have a list of the parties to this litigation, the numbers of the lots which they own, and their addresses. Such a list, with such information, and marked "APPENDIX DD'' is attached hereto and incorporated in this decision.

7. We now consider the nature and extent of Leuther Belcher's title, after his purchase of the twenty-three (23) acres of land in 1870, before he conveyed away any part thereof or interest therein, with particular reference to littoral rights and the nature, scope and extent of public right to use of area between low tide and high tide. We start by reviewing the description of the land as stated in the deed by which it was conveyed to Belcher. The deed first states that the land conveyed is "partly of upland and partly saltmarsh." It then describes some of the boundaries as being "on saltmarsh" which is identified by the owner or former owner thereof, or as being "saltmarsh of sundry persons." and then concludes the description of the land conveyed as being bounded "on Rock Island Creek, so called, easterly and southerly on the saltwater or however otherwise bounded." The description of the land thus conveyed to Belcher in 1870 clearly indicated that some portion of the land conveyed was bounded on salt water which ebbed and flowed with tidal changes.

8. The deeds to Belcher did not expressly state whether the land conveyed included the area between the high water mark and the low mark, and were silent on that subject. By operation of the law then in effect, the conveyance included the land between the high water mark and low water mark. This result followed by operation of some early colonial legislation which has been the the subject of discussion in numerous judicial decisions in this Commonwealth. That legislation has been most recently described as follows in Opinion of the Justices, 365 Mass. 681 , 685 (1974): as follows:

"At common law, private ownership in coastal land extended only as far as mean high water line. Beyond that, ownership was in the Crown but subject to the rights of the public to use the coastal waters for fishing and navigation. Whittlesey, Law of the Seashore, Tidewaters and Great Ponds (1932) xxviii-xxix. Commonwealth v. Roxbury, 9 Gray 451 , 482-483 (1857). When title was transferred to private persons it remained impressed with these public rights. Shively v. Bowlby, 152 U.W. 1, 13 (1893). The property inherent to the Crown in England was passed by charter to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and ultimately to the Commonwealth. Massachusetts Constitution, Part II, c. 6, art. 6. See Commonwealth v. Roxbury supra, 483-484. In the 1640's, in order to encourage littoral owners to build wharves, the colonial authorities took the extraordinary step of extending private titles to encompass land as far as mean low water line or 100 rods from the mean high water line, whichever was the lesser measure. Storer v. Freeman, 6 Mass. 435 (1810). This was accomplished by what has become known as the colonial ordinance of 1641-47, which is found in the 1649 codification, The Book of General Lawes and Libertyes, at 50. 'Every Inhabitant who is an householder shall have free fishing and fowling in any great ponds, bayes, Coves and Rivers, so farr as the Sea ebbs and flowes, within the precincts of the towne where they dwell, unless the freemen of the same Town or the General Court have otherwise appropriated them . . . The which clearly to determine, it is Declared, That in all Creeks, Coves and other places, about and upon Saltwater, where the Sea ebbs and flowes, the proprietor of the land adjoyning, shall have propriety to the low water mark, where the Sea doth not ebb above a hundred Rods, and not more wherewoever it ebbs further. Provided that such proprietor shall not by this liberty, have power to stop or hinder the passage of boates or other vessels in or throuqh any Sea, Creeks, or Coves, to other mens houses or lands.'

". . . In Commonwealth v. Alger, 7 Cush. 53 (1851), probably the leading case on the subiect, Chief Justice Shaw wrote, '[The ordinance] imports not an easement, an incorporeal right, license, or interest in, the soil itself, in contradistinction to a usufruct, or an uncertain and precarious interest.' Id. at 70. '[It created] a legal right and vested interest in the soil, and not a mere permissive indulgence or gratuitous license, given without consideration, and to be revoked and annulled at the pleasure of those who gave it.' In Butler v. Attorney Gen. 195 Mass. 79 , 83 (1907), it was said, 'Except as against public rights, which are protected for the benefit of the people, the private ownership [of the fee in the land between the high and low water marks] is made perfect,' and in Boston v. Boston Port. Dev. Co. 308 Mass. 72 , 78-79 (1941) this ownership in tidal land was deemed property of a 'substantial nature.'"

The origin, history and development of the law which places the ownership of land between low water mark and high water mark in the owner of the land bordering on the sea, absent some express provision or agreement to the contrary, has been the subject of numerous judicial decisions in this Commonwealth, continuing to this date. The most complete single cataloging of such decisions is to be found in the decision in Commonwealth v. Roxbury, 9 Gray 451 (1857) and particularly in "NOTE" at the end of the decision, at pages 503-528. The following are a few of the many decisions on the subject in this Commonwealth. Adams v. Frothingham, 3 Mass. 352 , 359-361 (1807) Storer v. Freeman, 6 Mass. 435 , 437-439 (1810). Commonwealth v. Charlestown, 1 Pick. 179 , 183-184 (1822). Commonwealth v. Alger, 7 Cush. 53 , (1851) with about forty pages of historical discussion. Boston v. Richardson, 105 Mass. 351 (1870). East Boston Company v. Commonwealth, 203 Mass. 68 (1909) which involved title flats around East Boston, "formerly called Noddle's Island", and a portion of the upland. The opinion by Chief Justice Knowlton states: "'The case was referred to a master . . . who heard the parties at great length in support of their respective contentions, and considered an array of references to books, records, documents and papers, English and American, bearing upon the construction to be given to the principal order in question, which shows investigation and research almost, if not quite, unequalled in any case ever tried in the courts of Massachusetts." Boston Waterfront Development Corp. v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 , 631-637 (1979).

9. It is appropriate at this point stress the very limited nature of the rights of the public to use the area between high and low water marks on salt water shores for fishing, fowling and navigation in contrast to the otherwise private ownership of that area which the colonial ordinances of 1641-47 "made perfect" for the benefit of the private owner of the adjoining upland property. The public rights of fishing, fowling and navigation have been held in a number of judicial decisions not to include the right to walk on the area and not to use the area for bathing. In Opinion of the Justices, supra, at 687-688, the Justices said: "We are unable to find any authority that the rights of the public include a right to walk on the beach. In a case presenting a very similar question to that [presented to the Justices for their opinions] it was held that the public rights in the seashore do not include a right to use otherwise private beaches for public bathing." In Butler v. Attorney Gen. 195 Mass. 79 (1907), the court said at 83-84: "In the seashore the entire property, under the colonial ordinance, is in the individual, subject to the public rights. . . Among these is, of course, the right of navigation, with a right to swim or float in or upon public waters as well as to sail upon them. But we do not think that this includes a right to use for bathing purposes, as those words are commonly understood, that part of the beach or shore above low water mark, where the distance to high water mark does not exceed one hundred rods, whether covered with water or not. It is plain, we think, that under the law of Massachusetts there is no reservation or recognition of bathing on the beach as a separate right of property in individuals or the public under the colonial ordinance." That same lanquage is repeated in the Opinion of the Justices, supra, 681, at 688.

While "walking on the beach" is not per se one of the public rights protected by the colonial ordinances of 1641-47, the walking may be protected if it is for the purpose of fishing by an "inhabitant who is an householder" within the meaning of the ordinance. See Barry v. Grela., 372 Mass. 278 (1977).

10. While it is customary to refer to the public rights to use the land of individual proprietors between high water mark and low water mark as the rights of fishing, fowling and navigation, I note, for completeness only, that at some time a question was raised whether some doubt was suggested as to whether the right to use the area for fowling had been nullified. For reference to this question, see Butler v. Attorney Gen. 195 Mass. 79 , 84 (1907). I express no opinion on that question, since fowling does not seem to be involved in this case, and we have enough other real issues requiring attention.

11. On the basis of the facts found as stated above, I further find and rule that, upon and by virtue of Leuther Belcher's purchase of the twenty-three (23) acre parcel of land on the Rock Island Head Penninsula in Quincy, on September 15, 1870, he also became the owner of the land located between the low water line and the high water line wherever the parcel purchased by him bordered on tidal sea waters; and that benefit was appurtenant to the forty-one (41) lots numbered zero (0) through forty (40) shown on the Richardson Plan of September, 1871, a reduced copy of which is APPENDIX A attached hereto and made a part hereof.

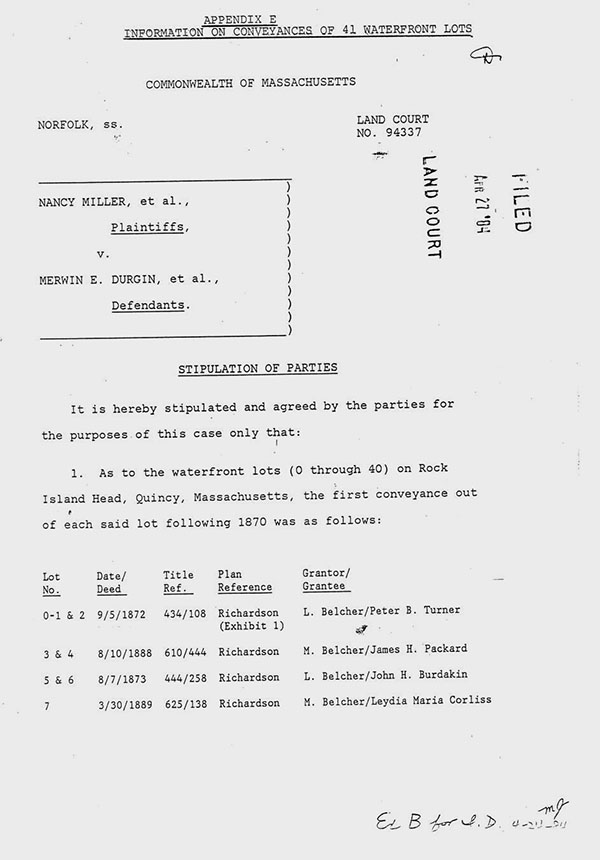

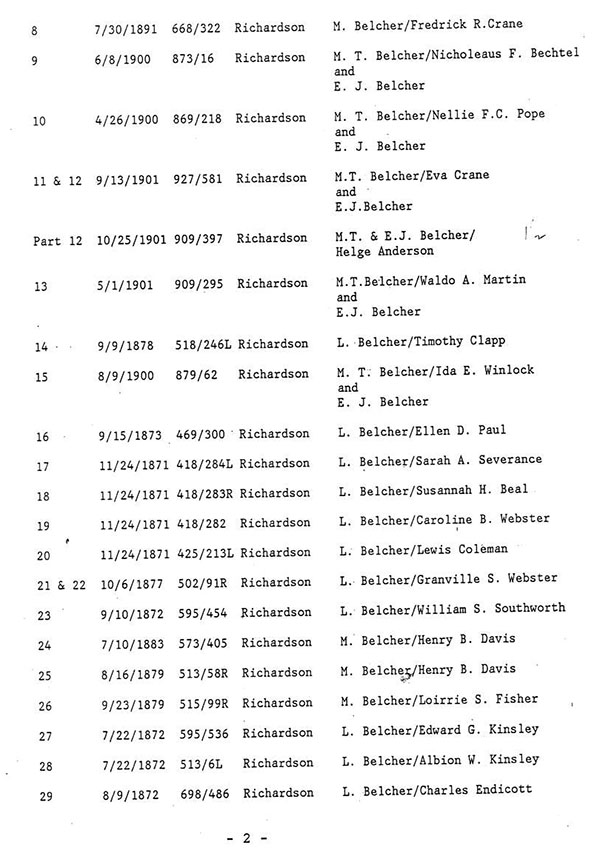

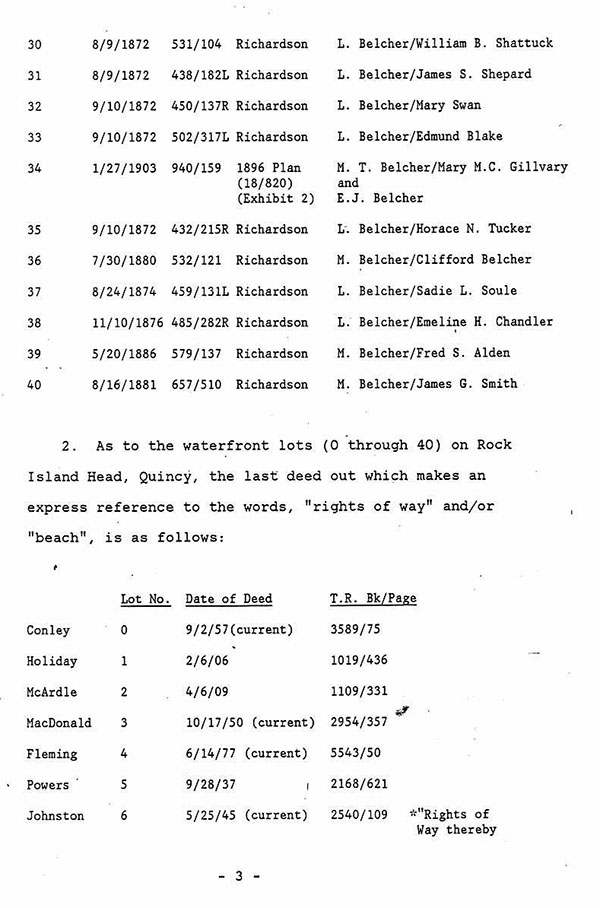

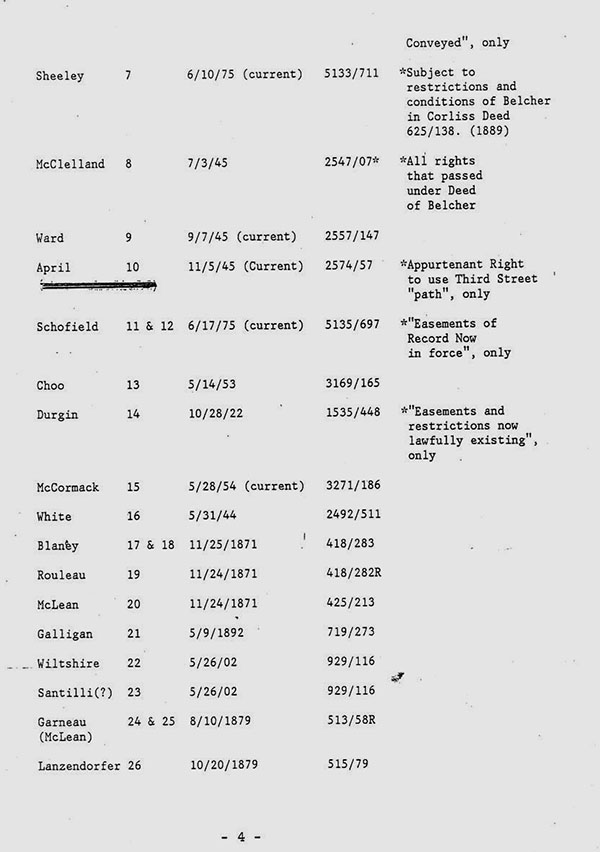

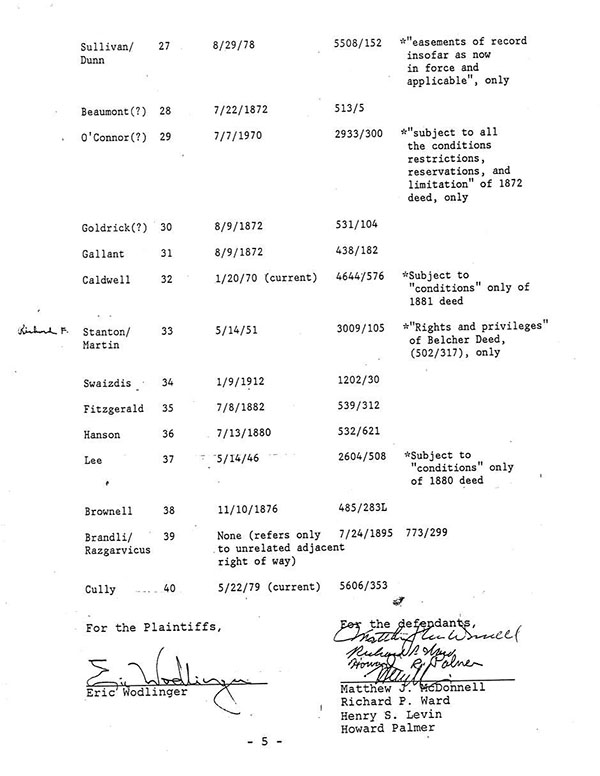

Thereafter Leuther Belcher conveyed away twenty-four (24) of those lots prior to his death on October 16, 1878. He devised the remainder of the real estate in question to his wife, Maria Belcher. Mrs. Belcher conveyed away ten (10) of those lots prior to her death on December 11, 1893. She devised the remainder of the real estate to her two daughters, M. Theresa and Ervilla Belcher. The daughters conveyed away the remaining seven (7) of the original forty-one (41) waterfront lots. The parties have stipulated as to the names of grantors and grantees, dates of conveyances, and Registry references as to all deeds by which the forty-one (41) waterfront lots were first conveyed by the Belcher family members, and by which each of the lots was most recently conveyed. A copy of the Stipulation marked APPENDIX E is attached hereto and made a part hereof.

12. In the preceding paragraphs I have found and ruled that wherever any part of the twenty-three (23) acre parcel owned by the Belchers bordered on tidal waters, the particular Belcher or Belchers then owning the portion of the land bordering the tidal waters also owned the fee in the land seaward thereof from the high water mark to the low water mark, or 100 rods from the mean high water mark, whichever was the lesser measure. The next subject to be considered is whether the Belchers, in conveving the forty-one (41) waterfront lots laid out in the Richardson Plan, conveyed with such lots any part of the land lying between the mean high water mark and the mean low water mark and seaward of whatever particular lot was being conveyed.

Before the trial of this case started, counsel for the parties filed pre-trial briefs. On page 2 of their pre-trial brief the plaintiffs state:

"The plaintiffs do not seek any monetary damages, . . . The plaintiffs' claims do not include any right of ownership in either the ways or the beach. The plaintiffs seek only to restore those rights of way and rights of access to and passage along and use of the beach which they formerly enjoyed" (emphasis supplied).

On paqe 3 of their pre trial brief, the plaintiffs quote the description by which Belcher conveyed Lot No. 19 on the Richardson Plan on November 25, 1871. That description, after identifying the lot number and the plan on which it appears, continues with the description as follows:

''. . . beginning on street of said Belchers at a corner of a private way thence 96 feet to the tide water: thence sixty ft. to lot no. 18: thence 96 feet by no. 18 to said street of Belchers: thence S 71 degrees E by said street sixty feet to the point begun at" (emphasis supplied).

The plaintiffs' pre-trial brief then continues, on paqe 3, as follows:

"Belcher's subsequent deeds contained similar descriptions, e.g. 'to the water', 'by the water', 'by high water', and the plaintiffs concede that the defendants own to the low water mark" (emphasis supplied).

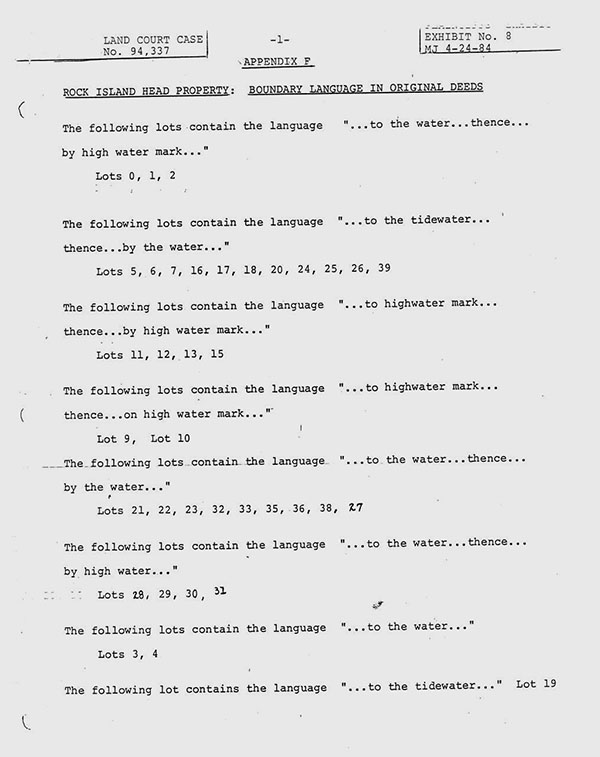

The plaintiffs' pre-trial express disclaimer of "any riqht of ownership in either the ways or the beach," and concession that "the defendants own to the low water mark" are sufficient to conclude those issues in favor of the defendants. Nevertheless, the plaintiffs introduced at trial a compilation of the language used by the Belchers in describing the waterfront line of the forty-one (41) waterfront lots laid out on the Richardson Plan, as each such lot was conveyed. A copy of that compilation, admitted in evidence as Exhibit 8 at the trial of this case, is attached to this decision as APPENDIX F and made a part hereof. That APPENDIX F consists of two typewritten pages, and it is entitled "ROCK ISLAND HEAD PROPERTY: BOUNDARY LANGUAGE IN ORIGINAL DEEDS." Because of the plaintiffs' disclaimer and concession described above as to the title to the land between high water mark and low water mark, and the resulting conclusion of that particular issue, this APPENDIX may serve no purpose other than its consistency with the defendants' reliance on the claim that the Belchers were involved in a long range scheme to develop an oceanside residential area, in several stages, in a manner which would give all lot owners access to the waterfront. Because I consider it unnecessary in the particular circumstances of this case to do so, I do not yield to the temptation to engage in an interesting and perhaps very lengthy discussion of the numerous judicial precedents which concentrate on the meaning of the words like "water", "tidewater", "waterfront", "beach", "shore", "to the water" or "along the water", "to the beach" or "along the beach", "to the shore" or "along the shore", "to the tidewater" or "along the tidewater". For a collection of the judicial precedents dealing with the meaning of these and other words common to similar cases, see Commonwealth v. Roxbury, 9 Gray 451 , and particularly that part of the lengthy note which is at pages 524 and 525. See also Hathaway v. Wilson, 123 Mass. 359 , 361-362 (1877); Litchfield v. Scituate, 136 Mass. 38 , 48-49 (1883); Haskell v. Friend 198, 200-201 (1907); Castor v. Smith, 211, 473, 474-475 (1912); and Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 491-492 (1933).

13. Notwithstanding the plaintiffs' pre-trial disclaimer of "any right of ownership in either the ways or the beach" and concession that "the defendants own to the low water mark", in their post-trial brief they state, on page 4, that "In this case, the question of title to the tidal flats is not free from doubt." That cryptic statement is not further explained except by reference to the fact that at some time the Land Court had recognized that the grant of one of the water front lots by the Belcher daughters to Wilton Dunham, the conveyance included both the lot in question and flats seaward. This court has insufficient evidence to determine what the circumstances of that Land Court case were, and it has no desire or authority to interfere with that case or the judgment therein.

14. In trying to decide the relative rights and obligations of the parties to the present litigation we have gone back in history more than a century - to 1870 when Leuther Belcher purchased his twenty-three (23) acres of land "at a place called Rock Island" in Quincy. We received evidence of what Belcher did with that land from the time he bought it to the time he died, what his widow did with it after he died, and what his two daughters did with it after the Belcher parents died. That ownership and development of the land covered a period of about thirty-three years, from 1870 when Belcher purchased the acreage until 1903 when the daughters are believed to have disposed of the last waterfront lot. This search through the records at the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds, and the testimony and evidence of what the records disclosed was aimed principally at determining what the Belchers said in documents which had been recorded and what their intent was when they said certain things in those documents and conveyed away various parts of the original twenty-three (23) acre parcel. From that history of what Belcher and other persons did with respect to that parcel of land, the court is asked to determine what the intent of Belcher and his widow and children was when they conveyed various portions of the parcel and what they meant and intended by the language which they used in doing so.

15. Belcher had his land surveyed in September, 1871, by a surveyor named Richardson, and he had Richardson draw a plan on the basis of the survey, showing forty-one (41) proposed lots numbered zero (0) throuqh forty (40), along a stretch where the property was bounded by tidal salt water. Most of the lots were about 6,000 square feet in size, some larger and some smaller. All of them bordered on a proposed road later named Rock Island Road, and all of them extended to the tidal water. Upon examination of the plan I infer that Belcher intended that the beach or shore on the ocean side of the lots would be used not only by the owners of those forty-one lots, but also by other persons going to the shore or beach by crossing at designated places between Certain of the lots as shown on the Richardson Plan. I draw that inference because of the fact that the Plan includes five (5) "PATHS" each ten (10) feet in width, running from the new road to the waterfront, plus another area called "Well Avenue" and shown on the plan as forty-three feet in width, also running from the new street down to the waterfront. Although the Belchers sold all of the waterfront lots, they did not convey away the five (5) "Paths" or Well Avenue. The waterfront lots took up only a part of the total Belcher property; and most of the land other than those waterfront lots was upland or inland from the waterfront.

16. The first of the waterfront lots which were conveyed by Belcher were the lots numbered seventeen (17), eighteen (18), nineteen (19) and twenty (20). All four deeds conveying those lots were dated November 25, 1871. Those deeds, and all other deeds by any of the Belchers conveying any of the waterfront lots numbered zero (0) throuqh forty (40) contained a "habendum" clause, as was the practice until the enactment in 1912 of the statutory provisions now found in G.L. c. 183, §§ 8-11, concerning statutory forms of Warranty Deeds and Quitclaim Deeds. The habendum clause as it appeared in the Belcher deeds of the waterfront deeds read as follows:

"To have and to hold the above granted premises with the privileges and appurtenances thereto belonging (including all riqhts of way from or to any public road and over all streets designated on said plan and over any portion of the beach adjoining the lots drawn on said plan and below high water mark in common with other owners of said lots . . ."

Except for the reference to "said plan", there was no evidence of any other document identifying or describing what the "privileges and appurtenances thereto belonging" were.

17. The plaintiffs contend that by using the language quoted above in all of the deeds by which they conveyed any of the forty-one (41) waterfront lots, the Belchers impliedly reserved, for the benefit of all of the inland remainder of the original twenty-three (23) acre parcel, easements over the "rights of way from or to any public road and over all streets designated on said plan [the Richardson Plan] and over any portion of the beach adjoining the lots drawn on said plan a below high water mark, in common with other owners of said lots."

Lawyers refer to such a situation as the creation or establishment a "scheme" for an intended development giving rise to these implied benefits to the expected or hoped for future purchasers of other parcels cut out of the same general development. I agree with that argument, and hold that the plaintiffs, as owners of inland lots, are beneficiaries of easements impliedly created for their benefit by the language used by the Belchers in the Habendum clauses of their deeds as quoted above.

It is apparent from what Belcher did that he intended to develop much or all of his twenty-three acre parcel, although not all at one time, and that he intended to do whatever was necessary to give purchasers of inland lots access to the beach by means of the paths and roads which were incorporated in his Richardson Plan of 1871. He was developing the waterfront first, but he was not foreclosing the opportunity for future inland lot purchasers to have access to the beach. See Ward v. Prudential Ins. Co., 299 Mass. 559 , 561-564, referring to a "general buildinq scheme." Anderson v. DeVries, 326 Mass. 127 , 133-134 (1950). Snow v. Van Dam, 291 Mass. 477 (1935), relating to schemes, with particular emphasis on building restrictions.

I hold that when Belcher had the Richardson Plan drawn up showing a number of paths or streets for access to the water front, and subjected the waterfront lots to the rights of others to use those paths or streets for access to the beach, he did so for the benefit of the inland portion of his original twenty-three (23) acres, and that the plaintiffs, as successors in title to some of that inland property, have the benefit of the rights of access to the beach to the extent that such rights have not been terminated or lost by abandonment, adverse position or laches.

The question whether such rights of access have terminated will be discussed later in this decision.

18. It should be noted that G L. c. 183, § 15, provides:

"In a conveyance of real estate all rights, easements, privileges and appurtenances belonging to the granted estate shall be included in the conveyance unless the contrary is stated in the deed, and it shall be unnecessary to enumerate them either generally or specifically."

19. The plaintiffs argue that the portion of the habendum clause (quoted in full in par. 16) which says "over any portion of the beach adjoining the lots drawn on said plan and below high water mark" should be construed to apply to a portion of any waterfront lot covered with sand to a point above the high water mark, and the defendants argue that the language in question limits the plaintiff to areas below high water mark. I agree with the position of the defendants. I see nothing in the habendum which recognizes any rights of the plaintiff in areas above high water mark except for the paths or ways giving access to the beach. I construe, "beach" as used in this particular part of the habendum as referring to an area between high water mark and low water mark.

20. The plaintiffs base some part of of their claim on the fact that in about a dozen of conveyances of waterfront lots by the Belchers, the habendum clause included a comma in the last two lines thereof so that they read: ". . . over any portion of the beach adjoining the lots drawn on said plan, and below high water mark in common with other owners of said lots) . . ." I do not believe that the presence or absence of a comma at that point changes what the Belcher grantors intended. I construe the words "portion of the beach adjoining the lots drawn on said plan and below high water mark" as referring to a portion of the beach adjoining a lot shown on the plan and which is below high water mark. I reiect the plaintiffs' argument on that point.

21. It seems obvious to me that Belcher's scheme of the development of his twenty-three (23) acre parcel centered around the fact that a substantial portion of the parcel bordered on tidal waters, that the successful development and sale of lots for sale required that the buyers be given rights of access to and use of the waterfront beyond the historically limited use of the land between high water mark and low water mark for navigation, fishing and fowling. I assume that even a century ago persons were attracted to the seashore for reasons beyond those three publicly permitted uses. I assume further that as a part of Belcher's scheme he saw a value in the land, both below and above the high water mark, if he controlled the fee to the area between high water mark and low water mark. He did control it by the language quoted from the habendum clauses on the deeds conveying the waterfront lots but at the same time applying a scheme by which the purchaser of inland lots had rights to reach and enjoy beach for its entire length, and for the width of the space between the high water mark and the low water mark, for the three uses available to the public, and, in addition thereto, it for walking, sunning, bathing, and boating, including the rafts, launching of boats, canoes, rafts, floats and other similar equipment of reasonable size and safety considering all of the circumstances, but not including the docking or anchoring of such boats, canoes, rafts, floats or similar equipment.

22. In summary I emphasize that the rights aquired by the plaintiffs as beneficiaries of the Belcher scheme for the development of the twenty-three acre parcel are limited to the following:

(a) the use of the streets, ways and paths shown on the three recorded plans for the purpose of access to the waterfront, which rights, when created, included no right to pass over, upon or across any part of any lot which the Belchers had sold, or which was being held for sale to purchasers or which they had sold to others: and

(b) the right to use the area seaward of the fortyone waterfront lots, such being for the purposes described in par. 21 of this decision, such area being limited however to that area between mean high water mark and mean low water mark, and subject to the 100 rod limitation imposed by the colonial ordinance of 1641-47.

The deeds of the Belcher contained a number of restrictions and conditions, for breach of which forfeiture was threatened, but they created no right in the plaintiff to use or go upon, over or across the lots of the plaintiffs.

23. On the basis of the facts which I have found and the rulings which I have made to this point in this decision, I conclude that after Belcher recorded the Richardson Plan of 1871, and after he had conveyed a substantial number of the waterfront lots shown on that Plan, certain easements were created by implication, entitling all persons who had purchased inland lots to have access to the waterfront lots by passage over any one of five (5) strips of land, each of which was ten (10) feet in width, and over another strip entitled "Well Ave.", all of which ran between what is now Rock Island Avenue and the tidal waterfront on which Lots Nos. 0 throuqh 40 as shown on the Plan bordered. After the recording of the 1896 Revision of that plan took place, and conveyances made on the basis thereof, there was an additional strip of land ten (10) feet wide, there were similar easements from the inland lots to the waterfront for access to the beach. The Belchers conveyed lots which were described as bordering on those strips and on Well Ave., but never expressly purported to convey the strips or avenue. In the early years the strips were numbered "First" through "Fifth" on the Richardson Plan, and in the revision of 1896, the strips were given names, and a Sixth similar strip appeared on the Plan. See APPENDIX B hereto for details on those strips. None of those strips was ever paved, and Well Ave. was not paved The strips have continued to this day to be what counsel called "paper streets" or "paper ways." At some time some, and perhaps all, of the strips or avenues were probably used by persons from the inland going to the waterfront, but of course, that is not something which is noted in any record in anticipation of a law suit which might come up a century later. Over those years nature and the neighbors have wrought changes to those strips. Some of the strips of land are overgrown with trees and brush, some are attractively adorned with shrubs, flowers and lawns, some have been occupied in part by encroaching structures and still others have been parceled off between abutting owners and fenced off for many years. The evidence produced at the trial even included a letter from a lawyer of one party abutting such a strip objecting to the other abutters attempt to fence the whole ten feet off as his sole property instead of splitting it between the abutters. Gradually most of these strips of land became incorporated into the yards and property of the abutters which improved the appearance considerably over what would have resulted if no one assumed responsibility for the condition of the property.

In 1979 these plaintiffs brought the present complaint alleging that the defendants had in various ways encroached on the strips and avenues over which the plaintiffs claimed rights of passage and other rights to use certain portions of the beach. The plaintiffs want a declaration of their rights and whatever injunctive relief to which they may be entitled.

24. The defendants have raised a number of grounds on which they contend either that no grant of an easement over the "paths" which are only ten feet wide; that if such easements are implied, they are implied, they should not be enforced because the plaintiffs have abandoned them; that if the plaintiffs have not abandoned them, they should be denied relief because they have been guilty of laches; and that if the plaintiffs have not been guilty of laches, they should be denied relief because any such easements have been extinguished by prescription. Because I believe that the easements over some of the paths have been extinguished by prescription, those should be dealt with first.

25. It is obvious from the evidence and the view which was taken that as to some of the ten foot ways or strips, the abutting owners had, for more than twenty years before the entry of this complaint, by their actions and conduct used and occupied such paths or strips of land openly and notoriously in manners inconsistent with and adverse to the existence of any easement rights of the plaintiffs to use the paths for travel to and from the waterfront. That was particularly and clearly obvious with reference to the following paths or strips of those ten feet wide: those which in the revised plan of 1896 were labeled First Avenue, Second Avenue, Third Avenue, and Sixth Avenue. No boundary markers were ever (in the period of more than twenty years before this action was started) placed in or on the ground to mark the locations of the ten foot strips. No part of the strips were paved in any way. Most of the owners of the lots abutting these avenues which we are now considering planted the area over which the plaintiffs now claim easements. The planting was varied, including trees, shrubs, fruit trees, flower plants, and various vegetables. There was nothing to indicate where the abutting owner's land ended and where the path or avenue commenced. The abutters of some of the paths or avenues had by agreement divided them and built fences from the street front to rear boundary of the lots. Some others cooperated in building fences either along the street line, or parallel with the street but at some distance back therefrom. As to these paths or avenues they were located between lots which had high grades down to the water line, and some which had steps leading from the lots to the water. There were no steps or stairs down the embankments of any of these four paths or avenues now being considered. If there were stairs, they were not at the locations of the paths or avenues, but elsewhere on the lots. These four paths or avenues were not used by the plaintiffs, their predecessors in ownership of the lots now owned by the plaintiffs, or by other owners of inland lots, for access to or return from the waterfront. I find and rule that the easement once formerly existing over or across the the paths more recently labeled First Avenue, Second Avenue, Third Avenue and Sixth Avenue for travel between the inward lots and the waterfront have been extinguished by prescription.

It is therefore not necessary to consider other grounds raised by the defendants as to these four paths or avenues.

26. The net effect of the findings and rulings in par. 25 above is that the plaintiffs' former easement for the use of First Avenue, Second Avenue, Third Avenue and Sixth Avenue for travel between inland lots and the waterfront have been extinguished. The court having found and ruled that similar easement had previously also been created or established by implication as to Fourth Avenue, Sixth Avenue and on Well Avenue, for travel between the inland lots and the waterfront, the court takes no action and they remain in effect. As to access to and from the waterfront at Turner Avenue no question was raised, no legal issue raised, and the court takes no action thereon.

27. Between 1968 and 1972 the Commonwealth constructed a new seawall all along the coastal boundary of the lots of the defendants. The Commonwealth did this after obtaining written licenses to do so from the owners of each of the lots and without making any taking of private property by the exercise its power of eminent domain. Before building the new seawall, the Commonwealth removed all of the individual sections of seawall which had been installed by the owners of each of the waterfront lots. The new seawall was then built in substantially the same position and location where the individual seawalls had been. However, in this process, the Commonwealth was not able to follow the exact location of the private walls in their many turns. Thus the finished product of the Commonwealth was straighter, wider and taller than the previous walls; and at some points the new wall was either further inward or further seaward than the individual walls had been.

The plaintiffs also claim that with the old seawalls they were able to walk all along the water front of the former Belcher property without having to walk in water even at high tide. That claim is disputed, as is their further claim that now it is not possible to walk along the same frontage without having to walk in water.

The plaintiffs also claim that with the old individual seawalls they were able to walk along a course which they cannot now follow because certain portions of the old course are now on the land side of the new seawall. They contend that they have a property right which entitles them to still walk the same course as they did before the new wall was built, even though some parts of that former course are buried under the mammoth new wall, or are buried deep under fill which was hauled to and dumped inward of the new seawall to bring the level of the lot up to the level of the new wall. If the plaintiffs attempted to walk along their old course in the post-new seawall conditions, they would be walking along the ground in some places, climbing up rip-rap and concrete of the new seawall at some places, walking along the narrow top of the new seawall for some distance, then across the filled and raised lot inside the new wall, continuing until they get back to some point where the new seawall is located on the land side of the course which the plaintiffs would have followed before the construction of the new seawall.

To make matters more difficult, the plaintiffs allege, many of the waterfront lot owners have had chain link fences installed along the whole length of the new seawall at their property, and for good measure many of those same owners have had similar fences installed on the side lines of their lots. Indeed they have installed such fences, and as to those on the top of the wall they obtained the permission of the Commonwealth to do so for safety reasons. The unfenced top of the new seawall present a hazard to children and adults as well, and the installation of the fence at the top of the wall was a reasonable safety measure. The plaintiffs contend that as to the fences on the side lines, in areas where they claim a right to walk across lots which have been filled in above the location of their original walking course, the defendants must either remove the fence or install gates so that the plaintiff may walk, without obstruction or interference, along the same course which they followed before the seawall was built, albeit some or many feet above the old course in elevation.

28. Certainly the plaintiffs have the right to resort to the courts for the protection and enforcement of their property rights, but their position on this point seems to be one of undue rigidity. I believe that the plaintiffs must fail on this point for the simple reason, if no other, that it is not reasonable when considering all of the circumstances. The Commonwealth certainly has the right and the responsibility to protect our ocean shorelines from erosion. Perhaps it could have exercised its power of eminent domain and subjected itself to a claim for damages by the plaintiffs, but it did not do so. The plaintiffs seek very broad injunctive relief which would require the defendants "to remove any and all fences, debris and other materials obstructing passage along the beach adjoining Lots 0-40 as shown on the Richardson and Whitman Plans and on that portion of the beach adjoining said lots below high water mark, and (2) enjoining said defendants from erecting any structures or fences, . . . on any part of the beach adjoining Lots 0-40 appearing on said beach and on that portion of said beach below the high water mark." This court will not grant injunctive relief ordering the removal of the fences in question.

29. The facts of this case as to the building of a new seawall, and the resulting accretion to the land of some of the defendants, seem very much similar in that respect to the facts involved in Michaelson v. Silver Beach Improvement Association, Inc. 342 Mass. 251 (1961). There the Commonwealth conducted a dredging operation which resulted in an accretion to ocean front property. The court said (p. 254) that "the beach was created solely by the Commonwealth in a relatively short time by its direct efforts. . . . (at p. 256) It does not follow, however, that the Commonwealth in carrying out such a project [dredging in aid of navigation] may cast the material dredged along the shore line of littoral proprietors and thereby cut off their exclusive access to the sea. The littoral or riparian nature of property is often a substantial, if not the greatest, element of its value. This is true whether the owner uses his access to the sea for navigation, fishing, bathing, or the view." At p. 258 the court continued: "A littoral owner takes his property with the knowledge that the boundary may change by accretion or reliction. This is a necessary condition of owning property along tidal waters. It is further assumed that coastwise and tidal currents may be altered by public works necessary for the fisheries or navigation. Such projects may drastically change the direction and force of the natural currents. But they are in accord with the traditional and essential governmental powers to which the riparian land is held subject . . . Consequently the law applicable to natural accretions should qovern . . . We see no reason why the fact that the land is created, as here, by dredging should require a different result."

In my opinion, the law stated in the Michaelson case applies to the present case, with the result that the plaintiffs are not entitled to climb up the seawall, walk along its top, or cross land created by the location of seawall seaward of the location of the previous individual walls. It follows also that the plaintiffs are not entitled to injunctive relief ordering the defendants to remove the fence in question or to install gates in that fence. The accretion accomplished by the relocation of the seawall may also push out seaward the path on which the plaintiffs claim the right to walk, notwithstanding the fact that there may be a difference in the extent to which the location of the new course is either more likely or less likely to require walking in water than was the case of walking on the course followed before the new wall was built.

31. The plaintiffs, in par. 63 of their complaint, allege that "[i]n addition to and apart from the foregoing, the plaintiffs' premises have the benefit of a prescriptive easement to walk upon, swim from, sunbathe upon and otherwise disport themselves upon the beach and land above and below the high water mark shown on the Richardson and Whitman [1902] Plans between the waterside lot lines of Lots 0-40," and they allege further that this "prescriptive right arises from the long continued and open use of said land by the plaintiffs, their predecessors in title and other residents of Rock Island Head."

Upon consideration of all of the evidence, and the weight and credibility thereof, I find and rule that the plaintiffs have failed to prove these allegations. The plaintiffs are entitled to no relief on this particular claim.

32. My comments, findings and rulings as to the allegations of the plaintiffs in par. 63 of their complaint apply equally to the plaintiffs' allegation and claim in par. 61 of their complaint.

33. Certain of the defendants filed counterclaims alleging that certain of the plaintiffs and other persons "constructed and built a pier and wharf on land on or adioining the premises at 306 Rock Island Road, Quincy, Massachusetts and on land on or adjoining the premises at 312 Rock Island Road, Quincy, Massachusetts (referred to as the 'pier and wharf')." The court was informed at the trial that the pier and wharf have removed and therefore makes no findings thereon.

34. There are a number of counterclaims which parties ask the court to find and rule that the defendants making the counterclaims have acquired certain real estate or rights therein by adverse possession or by prescription. I believe that those counterclaims are covered by the findings already made in this decision, although they are not matched specifically to those counterlaims. I do not believe that it is necessary to repeat those findings with reference to the counterclaims.

35. There are many parties to this case, many claims and counterclaims have been made. Many parcels of real estate are involved, some as to the ownership thereof and others as to easements or other rights therein. As to many of the parcels involved, it is indicated that they were subject to mortgages. It is desirable that the identies of the mortgagees be brought up to date if any court order is requested concerning them. It is possible that there may be some difference in the ownership of some of the parcels as the result of the passage of time since the trial. For all of these reasons, the court ORDERS as follows:

(a) That within twenty days from the date of this decision the parties shall file a stipulation, if possible, otherwise an affidavit, of any changes in the ownership or mortgage status of the parcels of land of any of the parties;

(b) that within thirty days from the date of this decision the parties hereto shall file suggested forms of a judgment or judgments to be entered for the disposition of the issues which were tried and have been decided above.

Entered: December 31, 1987

Francis J. Quirico; Retired Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, sitting on recall and special assignment as a Justice of the Land court for the purposes of this case.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

exhibit 4

exhibit 5-1

exhibit 5-2

exhibit 6-1

exhibit 6-2

exhibit 6-3

exhibit 6-4

exhibit 6-5

exhibit 7-1

exhibit 7-2