A dispute over the proper interpretation of parking rights retained by the declarant developer at Commercial Wharf on Atlantic Avenue in Boston in the County of Suffolk, and the validity thereof has led to this action; it arises from the parties' differences as to the proper construction of the rights intended to be conveyed to The Commercial Wharf East Condominium and those to be retained by the defendant Blue Water Trust ("BWT"), the declarant (called "Sponsor" in the Master Deed) and developer of the wharf in a document entitled "Declaration of Covenants and Easements" (the "Declaration") duly recorded with Suffolk Deeds Book 9083, Page 300. [Note 1] Although the complaint advances eighteen counts, primarily seeking diverse forms of declaratory relief, the basic issue concerns the parties' respective rights in the "Parking and Driveway" area, a common area of the condominium, and more particularly, the meaning of two phrases of the Declaration: (1) "to control and collect fees for the parking of vehicles" and (2) to "maintain and manage" the parking area as it existed in 1978. The creation of the condominium divided the premises originally owned by BWT into the "Condominium Land" and the "Retained Land." This conflict arises out of a dispute between the present owners of the land so classified as to where the ultimate power and control over parking on the Condominium Land resides, and the validity of such an arrangement.

The plaintiff association, representing both commercial and residential unit owners, seeks by this action to gain control of the common area and to rectify what it argues has been a detrimental change in the management of parking on the Condominium Land brought about by the practices of the defendant Waterfront Park Limited Partnership ("WPLP"), successor in title to BWT. The plaintiff contends that the phrase "control and collect fees for parking" permits management only of parking fees on the Condominium Land and not management of parking generally on that land as the defendants allege. The plaintiff further claims that the rights retained by the developer over parking on the Condominium Land pursuant to the Declaration violate G.L. c. 183A, §§10(b) and 5(c), constitute overreaching and are unconscionable. Therefore, the plaintiff argues, the Declaration, as interpreted by the defendants, is invalid as it violates these statutory sections and certain other general principles of law and equity.

The defendants variously answer and counterclaim that the Declaration conferred both benefits and burdens upon the owners of the Retained Land and therefore that their rights as to parking on the Condominium Land are a valid and enforceable covenant. Certain of the defendants (specifically BWT and more particularly today WPLP) contend that they have ultimate control as to the number of parking spaces on Commercial Wharf including the common area of the Condominium, the spacing thereof, and all other aspects of management of a parking lot. All of the defendants recognize the parking rights of the residential unit owners as spelled out in the Declaration, but argue that otherwise WPLP has the authority to run the entire wharf in this respect. The defendants point to the lack of any prior protest by the plaintiff regarding their parking practices as evidence of laches. They further respond that the condominium unit owners were all fully informed of their rights to parking at or before purchase and were represented by counsel which precluded any unfair surprise, breach of fiduciary duty, overreaching or unconscionability; they also argue, that the condominium purchase agreements did not constitute contracts of adhesion. They respond that the provisions of the Declaration were designed to afford a rational and convenient scheme for provision of access and parking to the condominium and to the owners of the other lots on Commercial Wharf. The defendants Marina Nominee Trust and Wharf Nominee Trust also advance cross-claims against BWT for damages and other relief should the parking rights deeded to them by BWT be affected. One of the commercial unit owners, The National Broadcasting Company, Inc., which at the time operated radio station WJIB, was granted leave to intervene as a party plaintiff on October 11, 1985 by Fenton, J.

There is also a companion case [Note 2] which was subsequently commenced in the Suffolk Superior Court, C.A. No. 87-3362, Bencion Moskow, et al, Trustees of Blue Water Trust vs. Charles J. McSweeney, et al. This second action was assigned to me for hearing by interdepartmental judicial designation pursuant to G.L. c. 2118, §9 upon Order dated August 3, 1987 by Chief Administrative Justice Mason. Thereafter, upon motion, the Superior Court action was stayed by Order of October 7, 1987 pending a final decision in the Miscellaneous case. The plaintiff's request for damages in this case pursuant to Count IV which advances a claim of Writ of Entry, pursuant to G.L. c. 237, §21, was, upon its own motion, postponed also by the same Order until resolution of the principal factual questions and of the proper construction of the relevant documents in the Land Court case.

The trial of this case was heard at the Land Court over fifteen days: October 27 to 30, 1987; November 4, 1987; December 14, 15, 16 and 18, 1987; March 21 to 24, and 28, 1988; and May 2, 1988. A stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony for each day of trial. Twenty-two witnesses testified of whom seventeen were called by the plaintiff and five by the defendants. The plaintiff called six condominium unit owners to testify: Nancy Royal, Joseph Collins, Robert Sachs, Mary Colpack, Dinah Gilburd, and Gordon Wagner. The plaintiff also called as witnesses: Harold Thomas, the condominium superintendent; Gary Hebert, a parking engineer; Anthony Tarricone, a principal in WPLP; Timothy Peltason, an associate professor of English at Wellesley College and chairman of that department; Burton Schafer, the attorney who represented Nancy Royal in the purchase of her condominium unit; Karen Ahlers, a legal assistant employed by the law firm representing the plaintiff; Ronald Cornew, a long-time resident of the waterfront area; Gunther Greulich, a registered land surveyor and registered professional engineer; Orrin Rosenberg, an attorney and formerly Chief Title Examiner for this Court; and Lawrence Scofield, an attorney employed by Lawyer's Title Insurance Corporation. The defendants called as witnesses: Mary Ellen Welch, a law clerk for the law firm representing WPLP; Linda Papkee (formerly Doherty) previously employed by BWT; Mark Lutwack, manager of Laz Parking, the present parking operator hired by WPLP; and Bencion Moskow and Arthur B. Blackett, trustees of BWT. One hundred twenty-one exhibits were introduced into evidence, certain of these containing multiple parts; all are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. Nineteen chalks were presented for the assistance of the Court and twenty-one items were marked for identification purposes only. Final argument was heard by the Court on June 28, 1988 and was electronically recorded. A view of the locus was taken by the Court on October 27, 1987, in the presence of counsel.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

1. The trustees of Blue Water Trust, the then owners of Commercial Wharf, the locus, created a condominium known as The Commercial Wharf East Condominium on a portion of the wharf by execution of a master deed dated August 8, 1978 and duly recorded in Book 9083 at Page 305 (Exhibit No. 4), and the submission of the real estate described therein to the provisions of General Laws chapter 183A. The master deed refers to the plan entitled "Plan of Land in Boston, Mass. - Commercial Wharf East Condominium" dated May 15, 1978 by Whitman & Howard, Inc. (Exhibit No. 82). The master deed was subsequently amended in its entirety on November 20, 1978 and the amendments recorded in Book 9120, at Page 337 (Exhibit No. 5). Just prior to the recordation of the master deed on August 8, 1978, the trustees of Blue Water Trust recorded the document entitled "Commercial Wharf East Condominium - Declaration of Covenants and Easements" (the "Declaration") in Book 9083 at Page 300 (Exhibit No. 3) which also refers to the said plan. The Master Deed incorporates the Declaration by reference in the description of the premises as "subject to and have the benefit of an easement declaration . . . granting certain access, parking and utility rights, said Easement Agreement being recorded at the Suffolk County Registry of Deeds, Book 9083, Page 300." The Master Deed (and as amended) further provides by the third paragraph of the paragraph numbered four that: "each unit shall have as appurtenant to it the right to rent one parking space on Commercial Wharf from the Sponsor subject to the provisions of the Easement Agreement above referred to,". This is in accordance with the Declaration which provided in paragraph 3 as follows:

3. The owners of the Retained Land covenant and agree to make available to owners of units then used for residential purposes in the building on the Condominium Land on a rental basis not less than sixty parking spaces. Said spaces shall initially be made available to unit owners receiving the first deed of a residential unit on the basis of one parking space per family. If a unit owner elects not to rent a parking space at such time, the owners of the Retained Land may rent such parking space to other unit owners or third parties. All such spaces shall be rented at reasonable and competitive rates. Said rentals shall be on a non-exclusive basis and subject to reasonable rules and regulations which may be promulgated from time to time.

The Master Deed went on record prior to all of the deeds out of the Retained Land.

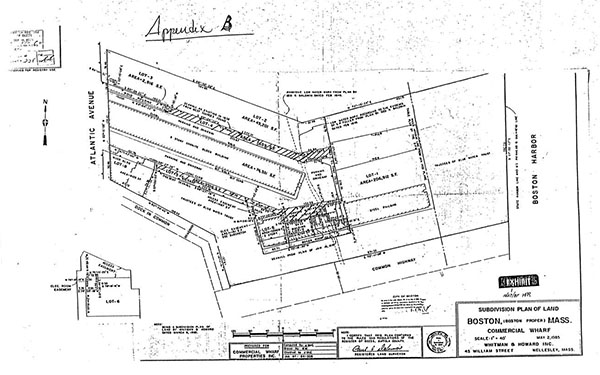

2. Commercial Wharf, the locus, is located on Atlantic Avenue on the Boston waterfront. The dominant physical feature of the wharf is the five story granite block warehouse building built in the 19th century which is now a mixed commercial/residential condominium (the "Condominium Building"). The wharf is located by the Boston Zoning Code in the M-2 use class which is an Industrial District requiring a floor-area ratio of 2.0 and the "Parking and Driveway" area as shown on the relevant plans. (See, for example, Appendix B attached hereto which is a reduced copy of Exhibit No. 1, the Whitman & Howard plan dated May 2, 1985) was included in the common area of the Condominium in order to meet this requirement.

3. The Commercial Wharf East Condominium occupies the lot at the center of the wharf and is composed of the granite block building and the paved Parking and Driveway Area which immediately surrounds the building to the north, south and east. The "Parking and Driveway" area (hereinafter "Parking and Driveway area") is a part of the common area of the condominium. There are also two narrow paved parking areas one north and one south of the condominium which were part of the area retained by the declarant Blue Water Trust when the condominium was created. These retained parking areas are delineated by the angled lines on Appendix B and consist of Lot 4 to the north and a portion of Lot 5 to the south.

4. From 1978 to 1979, BWT sold fifty-seven of the sixty residential condominium units in large part to then current tenants (Exhibit Nos. 45, 51, 52 and 64). The thirty-four commercial condominium units were sold during the period from 1980 to 1982. Mr. Moskow and Mr. Blackett each purchased a residential condominium unit, and Mr. Blackett presently continues to own his unit and was, until November of 1985, on the Managing Board of the Condominium. By the second sentence of the sixth paragraph of paragraph no. 4 of the Master Deed as amended (Exhibit No. 5), the Sponsor, Blue Water Trust, reserved the following rights:

. . . to use for storage, shop use and other purposes related thereto the cellar in buildings 59, 60, 65, 66, 67 and 68 Commercial Wharf and the portions of the cellar in buildings 34, 35, 36, 37 and 38 Commercial Wharf as delineated on the floor plans herein referred to.

At trial Mr. Moskow, an original trustee recalled the reservation of such basement areas of the condominium by the Master Deed. Mr. Moskow stated that such rights had been "deeded out" to Wharf Nominee Trust (Exhibit No. 7) and to WPLP (Exhibit No. 8) and some retained to date by BWT for records storage. The third paragraph of the deed of BWT to Wharf Nominee Trust does grant rights, as reserved, to the cellar of building 34. The deed of BWT to WPLP does not grant such rights to the basement area of the condominium. Mr. Moskow did not know if fees were paid to the Condominium Association for the use of these areas. However, the validity of such reservation is not at issue in this proceeding.

5. There are eight numbered lots on Commercial Wharf inclusive of its two finger piers which encircle the "Parking and Driveway Area" and the retained parking. These lots (1-8) were the premises retained (the "Retained Land") by the declarant, BWT, at the time of the creation of the condominium and are now owned by various defendants (and in one instance subject to a third party's life estate) and used for diverse commercial purposes including two restaurants, two marinas, professional offices and a steel warehouse formerly occupied by a lobster company.

6. The third paragraph of section 4 of the Master Deed, as amended, provides parking rights for the 94 condominium units (sixty residential units and thirty-four commercial units) as follows:

[E]ach unit shall have as appurtenant to it the right to rent one parking space on Commercial Wharf from the Sponsor [BWT] . . . (emphasis added)

7. The Declaration states its purpose at the outset as: "to create for the benefit of the Condominium Land certain rights and easements to use the Retained Land" and sets forth certain limitations thereon including the subjection of the Condominium Land to certain rights for the benefit of the Retained Land set forth as follows:

1. Declarant hereby grants to the owners from time to time of the Retained Land, and declares that the Condominium Land shall be subject to:

a. the non-exclusive right and easement to use the Condominium Land for vehicular and pedestrian access to the Retained Land for all purposes over the areas shown as "Parking and Driveway" on the plan entitled "Plan of Land in Boston, Massachusetts, Commercial Wharf East Condominium" Scale 1" = 40' dated May 15, 1978 by Whitman & Howard Inc. Engineers and Architects, which plan is recorded on even date (the Plan), including the right, subject to paragraph 2 hereof, to control and collect fees for the parking of vehicles in such area, subject to the right reserved to the owners of the Condominium Land to have adequate vehicular and pedestrian access to the Condominium building; (emphasis added)

Paragraphs two and three also relate to parking rights and privileges as between the residential unit owners and the owners of the Retained Land.

8. The Declaration provides, in paragraph two thereof, that the owners of the Retained Land shall "maintain and manage the Parking and Driveway area in the same condition as said land is in on the date hereof," inclusive of repairs, snow removal, security and public liability insurance.

9. By paragraph three of the Declaration the owners of the Retained Land covenant to "make available" to the unit owners "receiving the first deed of a residence unit" sixty (60) parking spaces for rental on a nonexclusive basis. This paragraph further provides, should such unit owner decline such rental, that the space may then be rented to other unit owners or third parties. All parking rentals are to be "at reasonable and competitive rates" and subject to "reasonable rules and regulations". The provision that the unit owner may decline such rental and the practices established by BWT in its conveyances on the wharf have given rise to two categories of parking rights: deeded rights and non-deeded rights. These latter arise by virtue of the provisions of the Master Deed together with the nonexercise of deeded rights and have taken the form, as have the deeded rights, of leases (Exhibit No. 102) and of licenses (Exhibit Nos. 31, 36A-C, 50, 61, 94, 119B-D). For example, Mr. Tarricone's recollection at trial was that in 1985 there were then a total of 220 outstanding parking licenses. The two categories of licenses (deeded and non-deeded) may be distinguished (albeit with difficulty) as non-deeded licenses would be grants to condominium unit owners or various owners of the Retained Land in excess of their deeded rights (See for example Exhibit No. 94), whereas deeded rights would fall within the categories represented by the Master Deed and the deeds out of the Retained Land. The parties stipulated at trial that condominium unit owners who desired to park on the wharf during the period of time from 1978 to the sale of "parking rights" to WPLP in 1985, could do so by entering an annual license agreement with BWT and that such unit owners were never denied a parking space. These annual parking license agreements also included a copy of the rules and regulations for parking on the wharf. These rules and regulations for parking were formulated by BWT without consultation with the plaintiff or objections therefrom.

10. There are, according to Mr. Hebert, the plaintiff's parking engineer, a total of 199 parking spaces currently available on the wharf on both the Condominium Land and the Retained Land. Mr. Hebert gave a breakdown of the total as: 100 spaces on condominium land, 18 spaces on retained land and 81 spaces bridging both condominium and retained land. The total number of non-exclusive parking rights created by the condominium and the subsequent deeds of BWT is 213. The history of these spaces is as follows: the condominium Master Deed granted the right to rent one parking space appurtenant to each of the units for a total of 94 (60 residential; 34 commercial); BWT in its deeds out of commercial units thereafter granted rights to 43 additional parking spaces as most of the commercial unit deeds granted rights to two licenses to park and two commercial units received rights to four licenses to park. [Note 3] BWT also deeded a total of ten irrevocable licenses with the deeds to Lots 2 and 3, and sixteen irrevocable licenses with the conveyance of Lots 4, 5 and 6 while retaining fifty-two spaces for BWT's account. These fifty-two reserved spaces were then disposed of as follows: twenty-six spaces were granted to East Commercial Wharf Limited Partnership; eleven spaces were conveyed to One Hundred Atlantic Associates Limited with the deed to Lot 8 (Cherrystones Restaurant) and fifteen were retained of which two went to the former Melvin & Badger Pharmacy which is now the 7-11 Store (Exhibit No. 14), and thirteen were reserved for Lot 7. The 7-11 Store is a commercial unit of the Condominium.

11. In June of 1984 BWT conveyed Lot 2, now the north marina and Lot 3, now the Sail Loft Restaurant, to Marina and Wharf Nominee Trusts respectively (Exhibit Nos. 6, 7 and 118). Lot 2 was conveyed by BWT to Marina Nominee Trust by deed dated June 22, 1984 and recorded in Book 10989, at Page 274 (Exhibit No. 6). This deed grants a right to irrevocable licenses for the parking of ten cars in the parking and driveway area as shown on the plan therein referred to (Exhibit No. 118) to be shared with the grantee of Lot 3. The Parking and Driveway area as so shown constitutes part of the common area of the condominium, and there was no express right reserved to use it for the benefit of the Retained Land in the Master Deed. The total of ten licenses are described as for the use of the employees of the grantee of Lot 3 (now the Sail Loft Restaurant) and the users of the marina and to be payable at a "standard monthly rate therefor as established by Licensor from time to time". The deed of Lot 3 from BWT to Wharf Nominee Trust which is of even date and recorded in Book 10989, at Page 281 (Exhibit No. 7) contains the same provisions.

12. In April of 1985 BWT conveyed Lots 4, 5 (the retained parking areas) and 6 as well as "parking rights" to Waterfront Park Limited Partnership ("WPLP") by deed recorded in Book 11518 at Page 5 (Exhibit No. 8). By this deed, BWT retained irrevocable licenses for fifty-two parking spaces, and WPLP was granted sixteen such licenses and the "Grantor's right to control and collect fees for the parking of vehicles in the 'PARKING AND DRIVEWAY' area" as shown on the 1978 plan recorded with the Declaration. This grant of the "right to control and collect fees for the parking of vehicles" also conferred upon WPLP the grantor's duties and obligations pursuant to paragraphs 2, 3 and 5 of the Declaration. The propriety of this grant to WPLP is one of the issues in this action. The conveyance of Lots 4 and 5 and the parking rights is made subject to the rights of Marina and Wharf Nominee Trusts pursuant to the deeds of BWT to them. The rights retained to fifty-two parking spaces were allocated after the commencement of this action in July of 1985 as previously described in Finding No. 10 and as detailed below. The grant and reservation of the total of sixtyeight parking licenses (fifty-two reserved and sixteen granted) also provided, by paragraph 4(b) of that portion of the deed entitled "Parking Rights", for the real location of the buyer's and seller's respective parking rights at a ratio of 4 to 1 in the event that the total of sixtyeight not prove feasible. Mr. Tarricone, as a principal in Waterfront Parking Corporation (which corporation is one of two general partners in WPLP), was involved in the negotiations and testified at trial that this provision arose from WPLP's concern for the number of licenses then outstanding (220) and from a concern for the potential loss of spaces below the high water mark to the public or due to catastrophe.

13. On September 6, 1985 the four trustees of BWT conveyed Lot 1 to themselves individually as tenants in common (Exhibit No. 10) with the right to licenses for "parking of an additional twenty-six (26) cars". By a second deed of the same date three of the four trustees conveyed their respective interests in Lot 1 to themselves as trustees of Blue Water Trust II ("BWT II") along with the entire right to the twenty-six parking licenses (Exhibit No. 11). By a third deed of even date (Exhibit No. 12) BWT II conveyed its interest in Lot 1 and the twenty-six licenses to East Commercial Wharf Limited Partnership ("ECWLP"). Arthur B. Blackett, the remaining fourth trustee of BWT with an interest in Lot 1 and the twentysix licenses then conveyed, by the fourth deed of September 6, 1985, his interest to ECWLP (Exhibit No. 13). Mr. Blackett is a general partner in ECWLP. There are two finger piers on Lot 1 for which there are, according to Mr. Blackett's testimony, tentative development plans either for residential housing or for a 95 slip marina of which twenty-seven slips currently exist as the marina known as "Boston Yacht Haven." The twenty-six parking rights reserved and conveyed by BWT would run to the residents, the marina would not have parking rights. The two existing finger piers each have an area of 12,000 square feet. The tentative residential development plan is to remove them, as they require reconstruction in any event, and replace them with a single new pier which would allow for construction of a new three story building having a total area of approximately 35,000 square feet which would be aligned at the same angle as the existing condominium building so as to preserve the views of the harbor.

14. By deed dated February 13, 1986 (Exhibit No. 9) BWT conveyed Lot 8 (now Cherrystones Restaurant, formerly Joseph's Aquarium Restaurant) to One Hundred Atlantic Associates Limited Partnership ("100 Atlantic") along with the right to eleven (11) parking licenses.

15. The remaining thirteen parking rights reserved by BWT were included in an option to purchase Lot 7, the Alden-Tillotson Building so-called, granted to Arthur B. Blackett. There is presently a life estate in Mr. Tillotson for exclusive use of the parking immediately adjacent to this building.

16. Three sets of admissions by statements contained in the second amended complaint were introduced as against the plaintiff by BWT both by the filing of papers and by reading into the record at trial on March 18, 1988. The first of these is the statement made by paragraph 15 of the second amended complaint:

15. Between August 1978 and April 1985, BWT managed the parking lot, provided security, snow removal and related services. Access was limited. Unit owners (and tenants) could park there. Provision could be made for preauthorized guests, for business invitees and others such as workmen or repairmen. The general public was excluded. Hourly or daily parking for fees did not exist. BWT was compensated for its management activities by unit owners (or tenants) who desired parking on Commercial Wharf. Payments of the annual rental were made on a monthly basis.

The second of these sets of admissions is contained in paragraph 59 of the second amended complaint:

59. Pursuant to the terms of the Declaration, which the plaintiff claims is invalid, Condominium unit owners paid BWT rentals on a monthly basis through April 1985 for parking on Commercial Wharf.

The third such numbered paragraph is 81 which reads as follows:

81. Paragraph 2 of the Declaration specifically requires the owners of the Retained Land to provide, among other things, "reasonable security at reasonable hours" for the parking area. Prior to Waterfront Partnership's assumption of the management responsibilities, a security guard was on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. [Note 4]

17. Two other sets of admissions were introduced by BWT as having been made by the plaintiff in its answers to interrogatories, were advanced by the filing of papers and were also read into the record at trial. The first of these is the plaintiff's answer to BWT's interrogatory numbered 7 which requests identification of facts or documents pertaining to BWT's alleged violation of any covenants in the Declaration which was answered in relevant part as follows:

. . . the Condominium Association has not sued Blue Water Trust for any violations of the covenants of the Declaration between the time of the Condominium's creation and the sale by Blue Water Trust of certain interests to Waterfront Partnership on or about April 9, 1985. To the contrary, prior (sic) April 9, 1985, the operation of the parking area was such that the Condominium Association had no notice that the terms of the Declaration could be so misconstrued as to grant the owners of the Retained Land the rights now claimed by defendants.

The second such admission is contained in the answer to interrogatory 8 as follows: [Note 5]

. . . the Condominium would note that it believes Blue Water Trust's letter of April 12, 1985 to be inconsistent with the conveyance documents. By that letter, Blue Water Trust stated that "The Commercial Wharf parking lot has been sold." To the extent that the letter suggests that Blue Water Trust in fact had the right to or did sell the parking area, it is inconsistent with the Declaration, the Master Deed, individual unit deed, etc.

18. By decision issued April 2, 1985, about the time of the conveyance from BWT to WPLP of the retained parking areas (lots 4 and 5) and the "parking rights", the City of Boston, Air Pollution Control Commission granted WPLP's request to add 125 spaces to the existing 100 spaces inventoried on the wharf (Exhibit No. 79). In July of 1985, WPLP again applied to the City of Boston, Environmental Department, for an exemption from the "Parking Freeze" (Exhibit Nos. 80, 108A and 108B). This application also sought a permit for the parking of 225 vehicles on the wharf. At no time did WPLP consult with the plaintiff as fee owner in making such applications. On December 3, 1985 the Air Pollution Control Commission issued a decision on the exemption which re-approved the previously issued exemption voted October 24, 1985 with "new capacity and provisos" (Exhibit No. 81). This Re-approval contains thirteen "provisos" or conditions including the following: a limit of 213 vehicles; parking only for "owners, residents, lessees, and employees of Commercial Wharf properties shown on the original site plan submitted to this Commission." (the permitted users are then particularized); a sign shall be posted at the entrance stating "Parking Limited, residents - employees - guests - patrons - patients - customers & clients of, (list of entities physically located on Commercial Wharf), Not Open to General Public."; non-stickered vehicles must have their tickets validated at their destination; and the guard booth will be manned "24 hours a day, seven days a week to enforce the aforementioned provisos and not allow the 'general public' to park on said facility." Photographs of the signs installed by WPLP were admitted as Exhibit Nos. 75-77.

19. By letter dated April 12, 1985 Condominium Unit Owners addressed as "Parking Licensee" were advised by BWT as follows: "the Commercial Wharf Parking lot has been sold to Waterfront Park Limited Partnership, . . ." (Exhibit No. 17).

20. The plaintiff's parking engineer Mr. Hebert testified that the parking spaces on the wharf are not of a uniform size. In deed, by the terms of proviso no. 9 of the open air parking permit issued to WPLP by the City on December 3, 1985 (Exhibit No. 81), the area along the southern wall of the condominium building is to be restricted to compact cars. Based upon a random sampling, Mr. Hebert found the parking spaces along the south seawall to be an average of 8' x 16' ; along the south side of the condominium building, an average of 8' x 13' ; at the east end of the condominium building, an average of 8' x 16' ; along the northern seawall, an average of 8' x 18' and 8' x 17' ; and along the north wall of the condominium building, an average of 8' x 20'. He also stated that a minimum parking space size for a standard sized vehicle should be 8.5' x 17' for so-called "head-in" parking and 8' x 15' for compact cars.

21. Prior to the conveyance of Lots 4, 5, 6 and the "parking rights" to WPLP (Exhibit No. 8) the restaurant located on Lot 8, then known as Joseph's Aquarium, offered valet parking (Exhibit No. 30). However, the vehicles of patrons were not parked by the valets on the wharf but elsewhere in the neighborhood although the restaurant management staff paid for licenses to park three cars on the wharf from time to time in the two or three spaces located parallel to the northerly wall of the restaurant (Exhibit Nos. 84A, 84E, 68B, 104 and 105). Presently Cherrystones Restaurant offers valet parking and up to forty vehicles are valet parked on the north side of the wharf on Lot 4. Eleven "deeded rights" to park were conveyed to 100 Atlantic by the deed of BWT (Exhibit No. 9). Prior to the sale of Lot 3 by BWT there was valet parking for patrons of a restaurant located in the building on that lot (presently occupied by the Sail Loft) pursuant to the provisions of a lease (Exhibit No. 102) given by BWT to Second Boston Corporation. The lease allowed for parking twenty vehicles on the north side of the wharf during evening hours only.

22. In July of 1985 after WPLP obtained the "parking rights" from BWT in April 1985, it removed the former guard booth to the right of the south entrance (Exhibit Nos. 18, 30, 87 and 88) and erected a new guard booth at the center of the entrance (Exhibit Nos. 22, 70C, 76 and 109A). No notice was given to the Condominium Association nor any permission obtained. One purpose of this removal and reinstallation was to create a two-way traffic flow at the south entrance. The new booth was also placed further from Atlantic Avenue to prevent back-up onto that way from vehicles entering the wharf and stopping at the booth.

23. Prior to April of 1985 the traffic flow on the wharf during the day was one way with the traffic entering at the south entrance past the guard booth and mechanical gate and exiting via another mechanical gate at the north by lot 4. The north gate was closed evenings, weekends and holidays. WPLP discontinued the use of the north gate as an exit by installing a fence and locked gate (Exhibit No. 23).

24. Prior to April 1985 the attendant at the parking booth was uniformed and would make rounds to verify that cars on the wharf were authorized and also to check the security of the buildings then owned by BWT. After April 1985 the attendant was no longer uniformed and did not make rounds. Under both BWT and WPLP the guard booth was, and now is, manned on a twenty-four hour basis. The open-air parking license from the City of Boston also required that the booth be manned on such a twenty-four hour basis (See para. 10, Exhibit No. 81).

25. Prior to the spring of 1985, parking along the southernmost seawall on Lot 5 was diagonal as was the parking along the southerly wall of the condominium building on the Condominium Land (Exhibit Nos. 19 and 74) and on Lot 4 along the northern seawall (Exhibit No. 20). The pavement in these areas was not striped to denote particular spaces. WPLP painted the entire parking lot with stripes to indicate particular spaces and rearranged the angle in these three areas from diagonal to perpendicular (Exhibit No. 95).

26. BWT permitted guests of condominium owners to park on the wharf without charge from 5:00 P.M. to 8:00 A.M. weekdays and on weekends. All guest delivery and repair vehicles were required to be identified in advance and deliveries were limited to five minute periods. (See for example rules attached to Exhibit No. 31 and Exhibit No. 62). Unit owners paid for repair or work vehicles parked for more than a week on a pro rata basis. After January 1, 1981 only guests of unit owners who had paid for a parking license were allowed to park free of charge (Exhibit No. 35). Guest parking after the end of 1985 was on a paid basis only at hourly rates. Deliveries are now allowed 10 minutes. Prior to April 1985 socalled "floating rights" to park might also be purchased on a monthly basis to accommodate guests or visitors. Presently a book of stickers may be pre-purchased for hourly parking of guests and visitors. Monthly licenses are also available in addition to the usual annual parking licenses. Pilgrim Parking, Inc. was hired by WPLP to operate the parking from April 1985 to the fall of 1986 (Exhibit No. 91). This contract and that with the present operator, Laz Parking (Exhibit No. 92) both provide by paragraph 6 thereof for compensation based on a percentage of parking revenues. Those who pay for parking on a monthly basis are given a magnetized plastic card which operates the gate. All others, the "temporary" parkers, so-called, pay hourly rates at the booth or by pre-paid sticker or do not pay in the case of short-term deliveries. Volumes of such hourly or "temporary" parking are given in Exhibit Nos. 103A-C. Mr. Tarricone testified that WPLP was considering a return to annual license arrangements for those holding deeded parking rights and adding a 30-day notice provision to all non-deeded parking agreements so as to give priority to those electing to exercise deeded rights should there prove to be a shortfall of available rights within the limits set by the city.

27. WPLP claims to have paid the taxes on the parking and driveway area by virtue of the inflated valuations of Lots 4, 5 and 6 (Exhibit Nos. 89A-C, 93A-C and Exhibits L and M for Ident. Only). Exhibit 89A, the 1987 tax bill for Lot 4 which has a total area of 7,659 s.f. shows as valued at $842,500 and it is contended that this reflects the valuation also for the rights retained over the "Parking and Driveway" Area. There was no testimony as to this from any City of Boston Assessing Department employee, and it is impossible to rule on the correctness of this position from the bill alone.

28. During the summer of 1987 the parking lot at Commercial Wharf was subject to increased congestion due to several construction and renovation projects. The proprietors of the 7-11 Store were making renovations to the old Melvin & Badger premises. WPLP was repairing the sewer main and Inc. Magazine was renovating its offices in the Condominium Building. A dumpster and storage trailer occupied parking spaces on the wharf during repairs to WPLP's building on Lot 6. Elevating devices occupied a certain number of parking spaces along the Condominium Building as balconies were being drilled and installed in that building.

The central issue in this litigation is first, the proper construction of the provisions of the Declaration and of the Master Deed as to the respective rights of the Condominium Association and the owners of the "Retained Land" in the "Parking and Driveway" area which forms part of the common area of the condominium. Secondly, the legal validity of the instruments as so construed must be determined. Inquiry into the construction of the Declaration was earlier determined by me in the Order Denying Diverse Motions for Summary Judgment dated October 7, 1987 to involve sufficient facial ambiguity so as to require resort to extrinsic or parole evidence inclusive of attendant circumstances and the course of conduct, especially as regards treatment of the "Parking and Driveway" area, by both the plaintiff, BWT and WPLP. While the condominium unit owners knew or should have known, through constructive, and indeed in most instances actual, notice that BWT would control, at least to some extent, parking on the wharf, the Court must determine whether it was apparent that BWT would claim complete authority over such parking including the ability to grant in deeds to the remaining land on the Wharf the appurtenant right to park specified numbers of cars and further the power to transfer the management rights for a very substantial sum to a third party, who in turn would syndicate the acquisition.

In summary, my findings are as follows: that the construction of the documents leads to the conclusion determination that the rights reserved by the grantor do not include any specific reservation of the right to park motor vehicles on the land of the condominium other than the ninety-four spaces initially set aside for the residential and commercial unit owners and in default of their exercise, to other unit owners or third parties; that the general scheme for the management of parking on the Wharf, however, contemplated a use of the Parking and Driveway Area for all the owners; that the rights to maintain and manage the Parking and Driveway area and to control and manage fees for parking are such that they constitute interests in real estate and run with the land, a designated portion of which may have the benefit thereof; that the very phraseology contemplates that the right to manage is to be exercised reasonably and on behalf of the owners ultimately of the fee simple estates in the land subject thereto; that such right may not continue for an unreasonable length of time and a measuring period either of the rule against perpetuities or of restrictions unlimited in time, G.L. c. 184, §23, would appear appropriate, but is reserved for decision after the decision of any appeals; and as to specific actions affecting the parking area and the changes from the manner in which it previously was run, this decision hereafter deals with those in particularity.

These central issues lead to a consideration of many disparate doctrines familar to conveyancers, for while the factual issues in this action are complex and the legal doctrines applicable thereto obscure at first impression, there are certain well developed principles of real estate law which are decisive as well as those now being fashioned in the developing field of condominium law. In addition to the proper construction of the documents relative to control of parking on Commercial Wharf, the following questions must be considered and the relevant legal principles applied: (a) the nature of the reservation by the owner of the Retained Land and the determination as to whether the rights so reserved run with the land; (b) a consideration as to whether such rights may be assigned to the owner from time to time of a portion of the Retained Land and if so, whether the reservation thereafter runs only with that portion of the premises; (c) once a determination has been made as to the nature of the reservation, then its validity must be weighed in the light of the general condominium law as found in c. 183A and applicable decisions of the Massachusetts appellate courts; (d) consideration must be given to the question as to whether the contracts between the sponsors and the unit owners were of adhesion and whether there was overreaching in their execution and delivery; and finally (e) the Court must determine whether the rights granted to the owners of Cherrystones Restaurant or of the Sail Loft for valet parking or otherwise (See Paragraph 21) overburden the rights reserved by the original owner of the Wharf. A concommitant inquiry arises as to whether the right to manage is superior in all respects to rights of the owners of the fee or whether it is subject to some reasonable control by the latter. Another facet of the legal issues is whether the easement reserved is limited by the rule against perpetuities or similar statutory preferences for freedom of real property from entangling encumbrances or whether the rights continue in perpetuity.

As the few reported Massachusetts cases in the field of condominium law indicate, the initial inquiry must be to the language at issue in the documents as viewed in light of the relevant provisions of the enabling statute, G.L. c. 183A, an enactment drafted and passed to provide broad, minimum guidelines so as to enable planning flexibility. E.g., Barclay v. DeVeau, 384 Mass. 676 , 686-687 (1981); Tosney v. Chelmsford Village Condominium Assoc., 397 Mass. 683 (1986); Beaconsfield Towne House Condominium Trust v. Zussman, 401 Mass. 480 , 482-483 (1988). These cases also seem to indicate that the broad language of c. 183A may permit the developer to reserve certain rights in the condominium common areas so long as such reservations accord with the statute and are clearly made in documents recorded prior to the master deed which is then made subject thereto or made clear by provisions in the master deed so as to furnish adequate notice thereof to possible unit purchasers. See Barclay, 384 Mass. at 681 and n. 10 (separation of ownership and management of common areas); Tosney, 397 Mass. at 688 (limited common area fees). See also Weiner v. Sacher, aff'd without op. 25 Mass. App. Ct. 1109 (1988) (reservation of additional parking spaces by developer for purposes of allocation); Wellesley Green Condominium Assoc. v. Spaulding, Suff. Supr. C.A. 98746, Report of Special Master, (Exhibit No. 117A) aff'd 16 Mass. App. Ct. 1104 (1983) rev. den. 390 Mass. 1102 (1983) (Exhibit Nos. 117C-117F) (reservation of additional parking spaces to be conveyed to unit owners in unit deeds, but not to others, does not violate the provisions of c. 183A, §1). In any event, as the foregoing cases have made clear, the declarant of a condominium is bound by the terms, provisions, reservations or lack thereof in the master deed and may not exercise powers over the condominium not provided for therein nor which are proscribed thereby, nor which violate the concepts of fairness or propriety. To some extent the unit owner also may be bound by provisions of which he has notice even if they otherwise might be unenforceable as without the purview of c. 183A. See Tosney, supra.

After reciting in the preamble that the purpose of the Declaration was to create appurtenant rights in the Retained Land for the benefit of the Condominium Land, the draftsman proceeded, at least in the initial paragraphs, to do the opposite. The Declaration in paragraph l (a) makes the Condominium Land subject to "the non-exclusive right and easement to use the Condominium Land for vehicular and pedestrian access to the Retained Land for all purposes . . ." This "right and easement" is later described in this same paragraph as inclusive of the right "to control and collect fees for the parking of vehicles in such area,". The Declaration then goes on to provide in paragraph two that the owners of the Retained Land "maintain and manage the said Parking and Driveway area in the same condition as said land is in on the date hereof, . . ." Paragraph three of the Declaration then requires the owners of the Retained Land to make at least sixty spaces "available on a rental basis" to the residential unit owners and retains the right to extend any such rental not used to "other unit owners or third parties" (emphasis added). It is not stated whether such rentals may be made applicable to Retained or Condominium Land and in practice the parties appear to have disregarded any such distinction.

The Master Deed provides that "each unit shall have as appurtenant to it the right to rent one parking space on Commercial Wharf from the Sponsor" subject to the provisions of the Declaration. The Master Deed does not distinguish, as to the exercise of these appurtenant rights, between the land within the Condominium and the remainder of the Wharf, and thus, unit owners may park on either. The reverse, however, is not necessarily true, for Chapter 183A proscribes the use by non-condominium owners of the common area unless such rights preceded the submission of the property to the provisions of the statute. The Declaration did not expressly reserve the right, for the benefit of the Retained Land, to park on the Condominium premises. While it is a close question as to whether such right is reserved by implication, the Declaration and Master Deed do seem to envision as a common scheme unified control of parking on the Wharf for the benefit of all owners without differentiation of the parking areas on Condominium or Retained Land. So long as the pattern was created prior to the condominium, it is unobjectionable. In my opinion, a right to park non-condominium vehicles in the parking areas of the Condominium legally could have been reserved in the Declaration since the Master Deed was subject to it, but it was done only by implication. Nonetheless, I find it a fair reading of the four corners of the Declaration that this was the scheme, that it was so understood by the parties, and operations by BWT dealt with all the land indiscriminately. However, the Master Deed itself could not grant rights in the common areas of the Condominium for use by third parties, and it did not attempt to do so.

The difficulty with the treatment of the parking areas in the documents stems from the history of the project. The so-called Sponsor (i.e ., BWT) originally intended to have the Condominium consist only of the Granite Warehouse Building without any surrounding land, but it was concluded that the Floor Area Ratio provisions of the Boston Zoning Code would be violated thereby. Accordingly, the Sponsor determined to establish a condominium but retain control in effect of much of its Common Area, i.e., the Sponsor would colloquially have his cake and eat it too, by casting the transaction in the framework of a deed out of the Condominium Land with a reservation of certain rights in the Common Areas which would allow BWT to manage the parking on Commercial Wharf. Unfortunately, the language in all respects did not make clear the result intended, and thus this litigation. In addition, the reservation of such control poses a serious question of validity under chapter 183A. It is clear that access across the condominium land was reserved [Note 6] in the instrument preceding its creation, and there is no question as to the validity of this provision. It is equally clear that no express right for third parties to park on the Condominium Land was reserved, except, in the case of default by a unit owner to exercise his rights to rent a parking space. As to the rights which were reserved, then how are they to be construed?

As regards the first of the three provisions of the Declaration set forth above, Professor Peltason's grammatical analysis concluded that the verbs "control" and "collect" modify the direct object "fees" and that "for the parking of vehicles" was a prepositional phrase which in turn also modifies "fees". The professor admitted that the insertion of a comma after the word "control" would cause it then to modify "parking". Facially then it appears that this phrase, contrary to the arguments advanced by BWT, was intended to allow the setting of rates and collection of fees and not "control" of the overall management of parking on Condominium Land. BWT's course of dealings, from 1978 to 1985, however, sustains its own interpretation, that with the added comma, as it formulated rates for annual parking rentals or licenses without consultation with the plaintiff and generally ran the operation. It appears that this interpretation and understanding was shared by the plaintiff and the unit owners as there were no objections raised as to this practice. Mr. Moskow testified that he told prospective unit owners that BWT would handle the parking as it was their "ballgame". Various unit owners testified that Mr. Moskow would also explain that the condominium had a "say" in how it was run since the parking area was owned by the unit owners in fee.

It is, however, the second paragraph of the Declaration which more nearly gives the total management rights and control of the Parking and Driveway area claimed by BWT and WPLP in providing that:

[T]he owners of the Retained Land at its own cost and expense shall maintain and manage the said Parking and Driveway area in the same condition as said land is in on the date hereof, (emphasis added)

This duty is then particularized, without limitation, to include snow removal, liability insurance for the benefit of the condominium association and security. It is difficult to know how broad the management powers are intended to be from a facial consideration of this language. These duties may or may not have been intended to be as broad as the defendants now argue, i.e., to manage and control the parking generally. The juxtaposition of the language is unusual, and clarity would suggest that it should have read, and indeed was intended to read, "manage and maintain" rather than the reverse.

Before continuing with an analysis of the propriety of the reservations for the benefit of the Sponsor's remaining land, it is appropriate to consider the validity of the rights retained. In effect, the Sponsor kept a perpetual right to manage the parking area and to collect all parking fees therefrom; at the same time the Sponsor incurred onerous obligations of maintenance which proved to be burdensome. The defendants analogize the rights which were kept to obligations imposed on granted premises by entities such as the railroad which historically has required its grantees to construct fences along their common boundary line and which more recently has imposed obligations to maintain stations which the common carrier was no longer able to do. See, for example, Boston and Maine Railroad v. Construction Machinery Corp., 346 Mass. 513 (1963) and Oak's Oil Service, Inc. v. Metropolitan Boston Transit Authority, 15 Mass. App. Ct. 593 , 601 (1983). One of the cases construing the obligations of the owner of land formerly benefitting the water power used to run the Lawrence mills is found in the case of Essex Company v. Goldman, 357 Mass. 427 (1970), where a property owner was obligated, the Supreme Judicial Court held, to continue to pay its share of water power expenses even though they no longer had any use for the power. Historically, the Massachusetts courts found it difficult to conceptualize such covenants as running with the land and in a characteristic short decision in Norcross v. James, 140 Mass. 188 (1885), Justice Holmes declined to find that a covenant not to compete ran with the remaining land of the grantor. This principle went through a gradual evolution, most recently in the case of Whitinsville Plaza, Inc. v. Kotseas, 378 Mass. 85 (1979); see Gulf Oil Corp. v. Fall River Hous. Auth., 364 Mass. 492 (1974); Shell Oil Co. v. Henry Ouellette & Sons, 352 Mass. 725 (1967); Shade v. M. O'Keefe, Inc., 260 Mass. 180 , 183 (1927), and now has been reversed.

The analogy to such cases is not controlling since the pattern in these instances involves the imposition of a burden on the servient tenant, whereas in the case before us the servient tenant is subjected to a right alleged to be appurtenent to the dominant estate to take the fruits thereof. In my analysis, the legal doctrine to which the relationship is most apposite is that of a profit a prendre which was most recently considered by the Supreme Judicial Court in First National Bank of Boston v. Konner, 373 Mass. 463 (1977), a case which originated in this department, albeit not an artificial profit, as here, designed by the developer. Here the Sponsor intended to maintain control of the parking area, obtain the fruits thereof and conversely, bear the burdens. While again this is a close question, I find and rule both that this is permitted by Massachusetts real estate law in the light of the realities of 1988 although conveyancers of another day might have had difficulty with the concept. I further find that as in American Telephone & Telegraph v. McDonald, 273 Mass. 324 , 325-6 (1930), the owner of such a right can grant to a third party a part thereof. Accordingly, I find and rule that the creation of a right to manage a parking lot and take the fees therefrom is not on its face impermissible and that such righs may be assigned or granted to a third party who owns land to which it can be appurtenant. Such a right, however, must be exercised reasonably. The power to manage a facility does not import ownership thereof; indeed the natural implication is that the facility is being managed for the benefit of the owners thereof, in this case the owners of the fee who have a supervening authority. The words used in the Declaration do not support the position of WPLP or BWT but rather impel a conclusion that the final source of power is the owners of the fee.

The plaintiff argues that the purchase and sales agreements between the Sponsor of the condominium and the unit owners were of adhesion, that the obligations could not be revised and that the purchasers were bound by the preordained framework of the existing arrangement if they wished to purchase the unit. Most of the unit owners were represented by counsel in their acquisition of their unit. It is obvious that in such a situation it is impractical for there to be sixty different purchase and sales agreements with varying provisions sought by attorneys for various purchasers, that the buyers had constructive, if not actual, notice of the provisions of the Declaration and Master Deed and accordingly, are bound thereby to the extent this Court upholds the provisions. There is no overreaching in the sense that the design of the project was not concealed from the unit owners, many of whom had considerable negotiating clout, although the written embodiment of the developer's plans was imprecise in its definition of what was contemplated, perhaps due to inartistic draftsmanship, perhaps to an evolution of the parking concept. There was no bad faith, moreover, in the submission of the property to c. 183A, but that does not forestall a decision that in part the design of Commercial Wharf so far as parking rights are concerned, contravenes certain provisions of applicable law.

The decision in Barclay v. DeVeau, 384 Mass. 676 (1981), in reviewing the legislative history and intent of §l0(a) of c. 183A found that the condominium association and the developer were apparently intended by the provisions of that section to be able to negotiate management of common areas and facilities. Id. at 681. The facts of this case are somewhat similar for, as in Barclay, one of the provisions at issue is a retention of ultimate control by the condominium association over the common area. Although here the Declaration of Covenants and Easements was not a condominium document and went on record prior to the Master Deed which was made subject to it, the issue of developer retention of control remains. While it is clear that the owners of the Retained Land and the Condominium Land require reciprocal rights to co-exist, this has not been accomplished by the documents. With the clarity of hindsight, the provisions and documents creating the scheme for parking on Commercial Wharf are obscure, and it is difficult to reconcile certain provisions in the Declaration and the Master Deed. It is uncertain from paragraph 2 of the Declaration that it was intended that all management and operation decisions over the common area of the Condominium Land rest with BWT as the original owner thereof. In the initial phases of the condominium, however, from 1978 to 1985, BWT managed the parking without complaint from the plaintiff or the individual unit owners. BWT formulated the rules and regulations for parking without consultation or objection from the condominium. Copies of these rules were provided with each annual license. The rules and regulations of the Condominium Association (Exhibit No. 34), by the section entitled "V. The Gate", state that the gate is the resporisibility of Commercial Wharf Properties and that the latter entity should be notified relative to security and maintenance of the lot. This provision seems to indicate that security and facility maintenance were the purview of BWT, yet these are narrower functions of operation and may not be indicative of the total control and management powers for which the defendants argue. When Mr. Moskow answered the questions of prospective unit owner Joseph H. Collins relative to parking on the wharf, he assured him that he would, as a unit owner, be able to exercise ultimate control over the parking as the condominium owned the fee. According to the deposition of Charles McSweeney (Exhibit No. 109B), Mr. Moskow thought it unlikely that indefinite retention of control by BWT over the Condominium Land would be upheld by the Courts although he described the plaintiff's ownership as "naked legal title." Mr. Tarricone, when describing the business of WPLP at trial, stated that it "owns and controls . . . the parking lot that surrounds the condominium building." In a letter (referenced in Finding No. 19) Linda Doherty announced, on behalf of BWT, to those holding parking licenses that the "parking lot has been sold." In 1985, WPLP applied to the City for an open air parking license without consulting the plaintiff, restriped the lot, installed a new guard booth and allowed valet parking for Cherrystones on the wharf. Thus the course of conduct by BWT maintained the parking pattern and the physical facility much as it existed in 1978 without objection from either the plaintiff or the condominium unit owners, but WPLP, in 1985, added and re-arranged the spaces, added valet parking and closed the north gate. 'These acts are alleged by the defendants to lie within their power to maintain and manage "as is" but appear to constitute a change in management from original practices, at least as to the number, size and arrangement of spaces and as to who is allowed to park, and to pass and repass over the Condominium Land. The large number of cars parked by valets with consequent abuses disturbed the unit owners. It was the changes in previous management practices that precipitated this lawsuit, rather than the concept of management by a condominium outsider.

There is no real dispute that BWT originally intended as the Sponsor of the Condominium to submit only the Granite Warehouse Building to the provisions of chapter 183A and that the surrounding land was added to the condominium to comply with the FAR requirements of the Boston Zoning Code. The Sponsor then attempted to exercise maximum permissible control over the common area to accomplish its original intention. The question remains as to whether this approach violates the provisions of the Code if indeed the documents are construed to give maximum control to the holder of the easement. The complaint is not framed, however, in terms of c. 240, §14A, nor was the City of Boston a party thereto. Another lawsuit on this issue awaits trial in the Superior Court. It is doubtful whether a serious question as to the effect of the zoning law on BWT's scheme should be raised collaterally in this action, but with the approach which the Court is taking here, the resolution of the conflict can be reached without determining this question. It is clear from the contents of the documents that BWT intended to develop the Retained Land further. There is the express reservation of the easement for vehicular and pedestrian access to the Retained Land and the installation of utilities contained in paragraphs l (a) and l (b) of the Declaration; the building height limitation on the Retained Land in paragraph 4 with its list of permissible uses presupposes additional construction. While there is now here an express reservation of a right to park non-condominium vehicles on the condominium land, the only logical conclusion is that this was intended, and one which I find and rule the unit owners were aware of and accepted prior to the management changes in 1985.

The provisions relative to parking contained in the Declaration and Master Deed, when viewed in light of the subsequent course of conduct of both BWT and WPLP, lead inevitably to the conclusion that these documents are more narrow in powers granted than those claiming under the owner of the Retained Land contend. Indeed, not only are the documents and the course of conduct schizophrenic, as herein before touched upon, there is a question in this litigation as to whether the reservation of rights in perpetuity over a common area of the condominium by the developer constitutes a violation of G.L. c. 183A. There also is a related question as to whether a developer may reserve such rights and thereafter grant certain of them to strangers to the condominium. While it has never been directly decided by the Massachusetts appellate courts, it appears unobjectionable for a real estate owner prior to the submission of his land to chapter 183A to grant or reserve rights affecting the locus for the benefit of other properties. The condominium then in its conception is made subject in the Master Deed to the provisions of the instrument already on record and if the provisions of it are unexceptional, the condominium association and unit owners should be bound thereby. They have constructive notice in any event and in many instances actual notice. In the Beaconsfield case, the dissent by Justice O'Connor seems to recognize this approach, and it is one followed by the Land Court in determining the validity of proposed Master Deeds affecting registered land generally. The majority opinion in Beaconsfield does not belie this approach since it focuses only on the time-bar aspect of the problem. A different question is presented, however, when in the Master Deed itself the declarant attempts to reserve rights for the benefit of strangers to the condominium. It is my opinion that this falls without the purview of permissibility afforded by c. 183A and is unenforceable by those claiming under the declarant. In Beaconsfield the principal question involved the statute of limitations with the Court deciding that an action attaching an insider lease was governed by the twenty year statute of limitations and thus was not time barred. The majority opinion suggests, however, that even though the lease went on record immediately prior to, but simultaneously with, the Master Deed, a question as to overreaching might arise in the factual situation there present, particularly where, as here, the documents were recorded simultaneously. The plaintiff in Beaconsfield also argued that a lease of the common areas was an invalid division thereof, but it would appear that the statutory reference in fact is to the conveyance by a unit owner of a right in the common area to a third party apart from the unit deed or a petition for partition, and that is not our present case. As to the solution of the question whether a reservation which precedes the creation of the condominium might constitute overreaching or a breach of fiduciary duty, no help can be found in the decided Massachusetts cases in this area. While the Barclay case upholds retention of control by the declarant, this was for a limited period of time and not a right in perpetuity as in the present case.

The decision of Justice King of the Housing Court in Miller v. Hurwitz, No. 17143, sustains the position that the developer stands in a fiduciary relationship to the unit owners analogous to that of a corporate promoter citing Whaler Motor Inn v. Parsons, 372 Mass. 620 , 626 (1977). It may be that there is here a duty to disclose self-dealing but it is also true that the Declaration to which both the Master Deed and the unit deeds refer reserved management rights, and thus the plaintiff is chargeable with constructive notice. Whether we treat BWT as subject to the rules of the Old Dominion, Copper Mining & Smelting Co. v. Bigelow, 188 Mass. 315 (1905) S.C. 203 Mass. 159 (1909), or whether we divorce it from any fiduciary duty, does not affect the result I reach here. The nub of the plaintiff's position is that it holds title to the Condominium Land but that it is subject to the control of a third party in perpetuity. Plaintiff contends that this exceeds the permissible limits prescribed by chapter 183A for condominium common areas. The defendants point to the report of the Special Master in Wellesley Green, affirmed by the Superior and Appeals Courts, for guidance, but that situation concerned in-house parking by condominium unit owners, not control by strangers and clearly is distinguishable.

Two acts by WPLP, alleged by the Association to be excessive, appear to have triggered this litigation: (1) WPLP's change in the modus operandi of the Commercial Wharf parking as exemplified by BWT, most particularly the valet parking of as many as 40 cars for Cherrystones and (2) the restriping of the parking lot. The change in the traffic flow also contributed to the generation of the dispute. I find and rule that the execution of forty licenses for valet parking to Cherrystones is a clear change in previous management practices and an overburdening of the reserved easement to Lot 4 over the Condominium Land. [Note 7] The restriping, however, may qualify, within reasonable limits, as the type of "maintenance and management" contemplated by paragraph 2 of the Declaration. Prior to BWT's conveyance in 1985 of the "parking rights" to WPLP there was no striping to denote individual parking spaces (See Exhibit Nos. 19, 20 and 74). WPLP striped the parking lot but did so in such a fashion that only compact cars were allowed to park along the south wall of the Condominium Building, allegedly pursuant to the City's open air parking license. It is notable, however, that WPLP alone applied for the license without joining the owner of the fee, and by the terms of the application may have predetermined this condition. There was evidence from the testimony of Mr. Hebert that the paved area on the south side of the Condominium Building inclusive of Lot 5 was not presently wide enough to accommodate a two way traffic aisle bordered by two rows of full-sized spaces. It is also evident (See Exhibit Nos. 84A-840) that full-sized cars parked on Lot 5 encroach upon the Condominium Land. It is clear therefore, that a return to the former diagonal parking pattern is advisable on one or both sides to enable full-sized parking on both sides or that the compact parking should be required on Lot 5 if the head-on pattern is retained. The change by WPLP of the parking angle from diagonal to head-on and the requirement of compact parking only along the southerly wall of the Condominium Building may, especially in light of the legal effect of the documents, be a violation of the "covenant" so-called of paragraph 2 of the Declaration to "maintain and manage" the "Parking and Driveway area" as it was in 1978, and I so find and rule.

These two acts, done in 1985, the year this suit was commenced, changed the parking as it was and defeat the defense of laches. The defense also fails as applied to the conveyances by BWT of parking rights in excess of the rights reserved in the Declaration and Master Deed as the deeds of Lots 1-6 and 8 were made with "appurtenant" parking rights in the period from 1984 to 1986 (Lot 8 was conveyed after commencement of this action). In any event, only the deeds to Marina and Wharf appear to apply to the Condominium Land. To the extent the plaintiff complains of overreaching in the original documents, the defense of laches fails as well for it was not until after the sale by BWT of its right to manage the parking that the breadth of the defendants' claims became apparent.

Prospective unit owners, according to the testimony of witnesses for both sides were told by representatives of BWT, Mr. Moskow in many cases, that the condominium would own the parking lot but that BWT would handle the details of operation. Mr. Blackett further testified that BWT believed it had the right to issue licenses to park on condominium land to those outside the condominium, the right to determine the number of licenses to be issued and the right to determine how the parking spaces would be arranged on the lot. He also stated that he never personally informed unit owners of BWT's belief it had retained the right to deed or to issue temporary parking licenses to those outside the condominium, although Mr. Moskow might have by non-condominium provision as to Declaration. Thus, the only notice of BWT's intent to permit parking owners which is chargeable to unit owners is the "third parties" contained in paragraph 3 of the Declaration.

In summary, therefore, on all the evidence I find and rule that the operation of a parking area at Commercial Wharf since acquisition by WPLP departed materially from the previous practices of BWT, including the two way driveway, the hourly parking for cash, the striping of the parking lot and the valet parking by Cherrystones; that such major changes in operation required the approval not to be unreasonably withheld of the fee owner of the premises; that the question as to whether hourly parking for cash as against the previous policy of "floaters" was preferable is a decision that should be shared with the plaintiff; that it was appropriate to stripe the parking spaces in order to properly allocate spaces, but that angle parking rather than perpendicular spaces may better serve the needs of the Wharf community; that there was no express reservation in the documents of the right to park automobiles owned by non-condominium unit owners on condominium land other than for the balance of the spaces, if any, not preempted by the unit owners pursuant to the provisions of the Declaration and the Master Deed, but that such a right clearly was implied; that a profit a prendre of limited duration in the nature of the present right to manage and collect parking fees is not unreasonable but that the duration should be limited to a period consistent with the rule against perpetuities or that imposed by the General Court on restrictions if we treat the reservation as in effect a restriction. See c. 184, §23, Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 (1967); Myers v. Salin, 13 Mass. App. Ct. 127 , 133-135 and n. 6 (1982), such period of limitation to be decided hereafter once any appeals are decided; that the rights here in dispute are such that they do run with the Retained Land and with a portion thereof as granted by the original predecessor in title of all parties; that they must, however, be exercised reasonably and in conjunction with the unit owners; and that there was no overreaching in the original sale of condominium units that would result in the invalidity of either provisions in the Declaration or the Master Deed. There are certain questions about the condominium itself and the validity of rights reserved therein which became apparent during the trial which were not a focus of this litigation and which the Court does not reach in fashioning this decision.

Judgment accordingly.

COMMERCIAL WHARF EAST CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION, an unincorporated association, vs. WATERFRONT PARKING CORP. and THE WATERMARK CO., INC., as general partners of the WATERFRONT PARK LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; RICHARD C. KANTER, FREDERIC S. CLAYTON and SALVATORE J. DIGNOTI as trustees of MARINA NOMINEE TRUST; RICHARD C. KANTER, FREDERIC S. CLAYTON and SALVATORE J. DIGNOTI as trustees of WHARF NOMINEE TRUST; ARTHUR B. BLACKETT, CHARLES W. BROWN, III, KONRAD GESNER and BENCION MOSKOW, as trustees of BLUE WATER TRUST; CHARLES W. BROWN III, KONRAD GESNER and BENCION MOSKOW, as trustees of BLUE WATER TRUST II; ARTHUR B. BLACKETT as general partner of EAST COMMERCIAL WHARF LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; and THE WATERMARK - ATLANTIC CO. and USB ATLANTIC ASSOCIATES - 85, INC. as general partners of ONE HUNDRED ATLANTIC AVENUE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP.

COMMERCIAL WHARF EAST CONDOMINIUM ASSOCIATION, an unincorporated association, vs. WATERFRONT PARKING CORP. and THE WATERMARK CO., INC., as general partners of the WATERFRONT PARK LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; RICHARD C. KANTER, FREDERIC S. CLAYTON and SALVATORE J. DIGNOTI as trustees of MARINA NOMINEE TRUST; RICHARD C. KANTER, FREDERIC S. CLAYTON and SALVATORE J. DIGNOTI as trustees of WHARF NOMINEE TRUST; ARTHUR B. BLACKETT, CHARLES W. BROWN, III, KONRAD GESNER and BENCION MOSKOW, as trustees of BLUE WATER TRUST; CHARLES W. BROWN III, KONRAD GESNER and BENCION MOSKOW, as trustees of BLUE WATER TRUST II; ARTHUR B. BLACKETT as general partner of EAST COMMERCIAL WHARF LIMITED PARTNERSHIP; and THE WATERMARK - ATLANTIC CO. and USB ATLANTIC ASSOCIATES - 85, INC. as general partners of ONE HUNDRED ATLANTIC AVENUE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP.