EDWARD VIEIRA vs. TERESA DEBARROS

EDWARD VIEIRA vs. TERESA DEBARROS

MISC 122163

July 7, 1988

Plymouth, ss.

CAUCHON, J.

EDWARD VIEIRA vs. TERESA DEBARROS

EDWARD VIEIRA vs. TERESA DEBARROS

CAUCHON, J.

This cause came on to be heard upon the plaintiff's complaint to remove a cloud on title to a certain parcel of land containing 21,965 square feet with a building thereon ("Lot A") located at 195 Plympton Street in Middleboro, Massachusetts. The defendant has counterclaimed asking that she be declared a fifty percent owner of said Lot A.

A trial was held on January 25, 1988 at which a stenographer was sworn to record and transcribe the testimony. Four witnesses testified and three exhibits were introduced into evidence, which exhibits are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal.

The following facts are undisputed:

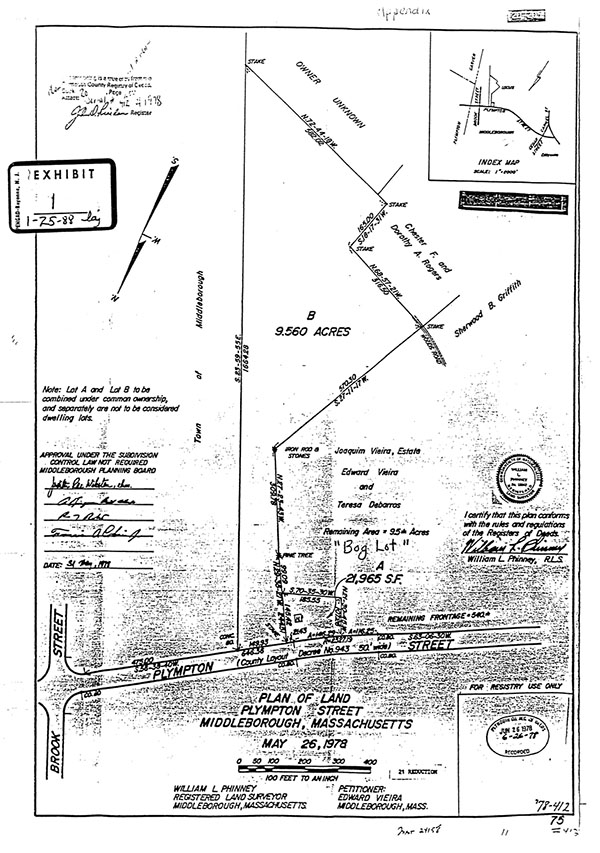

1. The plaintiff is the record owner of two parcels of land shown as Lots A and B on a "Plan" (Exhibit 1) entitled "Plan of Land, Plympton Street, Middleboro, Massachusetts" dated May 26, 1978 by William L. Phinney, Registered Land Surveyor and recorded at the Plymouth Registry of Deeds, Book 20, Page 205. [Note 1] (See Appendix.)

2. The plaintiff and the defendant each received one-half interests in Lot A and an adjoining 9.5+ acre lot (the "Bog Lot") shown on said "Plan" through the estates of their parents, Joaquim and Mary Vieira. The Bog Lot had been utilized by Joaquim Vieira and the plaintiff as a cranberry bog prior to Joaquim's death and has continued to be so utilized by the plaintiff to date. Profits from the cranberry bog operation have been divided equally between the plaintiff and the defendant.

3. On June 21, 1978, the defendant conveyed all her right, title and interest in Lot A to the plaintiff by deed recorded at Book 4477, Page 223 (Exhibit 2), retaining her one-half interest in the Bog Lot.

4. On December 6, 1978, the plaintiff obtained a $13,000 mortgage on Lot A from the Plymouth Fderal Savings and Loan Association recorded at Book 4582, Page 131 (Exhibit 3).

5. The plaintiff acquired Lot B, a 9.56 acre lot, from his uncle, Albino V. Centeio, on May 17, 1982 by deed recorded at Book 5149, Page 450.

Based upon all the evidence, I also find:

6. Lot A and the Bog Lot were purchased in 1945 by Joaquim Vieira. Three acres of the Bog Lot have been worked as a cranberry bog from 1945 to the present. Joaquim Vieira died in 1966.

7. The plaintiff began to live in the building on Lot A in 1971. At this time, he brought his partially blind uncle from South Carver to live with him. The condition of the house was poor with no bathroom facilities, limited electricity and was heated by a wood stove.

8. On or about 1978, the plaintiff approached his sister and her husband, who were then and are presently residing in Connecticut, with a proposal to purchase the defendant's share of Lot A in order that the plaintiff could obtain a mortgage and make improvements on the house on Lot A.

9. Since 1978, the plaintiff has added bathroom facilities and a gas stove, constructed a barn and made substantial repairs and other improvements to the house. The plaintiff's uncle died in 1985. The plaintiff now resides in the house with his wife.

The controversy herein involves an oral agreement between the plaintiff and the defendant, the result of which was the deed dated June 21, 1978. The defendant alleges that in return for executing the deed, the plaintiff promised either to reconvey a one-half interest in Lot A, to compensate the plaintiff monetarily or to give the plaintiff the equivalent value in land from the Bog Lot. The defendant asks the Court to find an express trust, a resulting trust or a constructive trust in her favor and to declare her the owner of a one-half interest in Lot A.

The plaintiff admits that the 1978 conveyance from the defendant to himself was not a gift. The consideration, however, was that the defendant would be given a right of first refusal upon his selling Lot A or an extra one-half acre of upland when the Bog Lot was partitioned.

The defendant admits that she has made no payment toward improving Lot A since 1978 nor any payments on the $13,000 mortgage used to improve the house on Lot A.

G.L. c. 203, §1 sets forth the applicable law on the creation of trusts concerning land:

No trust concerning land, except such as may arise by implication of law, shall be created or declared unless by a written instrument signed by the party creating or declaring the trust or by his attorney.

In the case at hand, the statute of frauds, G.L. c. 259, §1 and G .L. c. 203, §1 have been properly pleaded by the plaintiff, and as there has been no evidence of a written instrument introduced, no express trust exists. A resulting trust is also inappropriate based upon the facts described above. See Moat v. Moat, 301 Mass. 469 , 472-473 (1938); Druker v. Druker, 308 Mass. 229 , 230-231 (1941).

The defendant claims a constructive trust should be employed by this Court to avoid the unjust enrichment of the plaintiff. The Supreme Judicial Court discussed the requirements of a constructive trust in Kelly v. Kelly, 358 Mass. 154 , 156 (1970).

A constructive trust "is imposed 'in order to avoid the unjust enrichment of one party at the expense of the other where the legal title to the property was obtained [a] by fraud or [b] in violation of a fiduciary relation or [c] where information confidentially given or acquired was used to the advantage of the recipient at the expense of the one who disclosed the information' [emphasis supplied]. Barry v. Covich, 332 Mass. 338 , 342 (1955)." Meskell v. Meskell, 355 Mass. 148 , 151 (1969).

There is no evidence before this Court of fraud or confidential information used by the plaintiff to the disadvantage of the defendant. However, the issue of obtaining legal title in violation of fiduciary relation does arise. While Massachusetts law holds that "a confidential relationship does not arise merely because the conveyance was made between members of the family, . . . ." Meskell v. Meskell, 355 Mass. 148 , 152 (1969), "additional factors may give rise to such a relationship." Kelly at 156, citing Samia v. Central Oil Co. of Worcester, 339 Mass. 101 , 112 (1959). See also Hatton v. Meade, 23 Mass. App. Ct. 356 , 364 (1987).

I find and rule that the plaintiff brother was in a fiduciary relationship with the defendant sister based upon his operation of the cranberry bog and his handling of the business and the financial affairs for the family. There is no question that the defendant relied on her brother's handling of the parents' estates and other family business due to her Connecticut residence and that a trust relationship existed between them from the execution of the deed in 1978 up until the discussions held in 1985 after the death of their uncle.

Based on the facts as set forth above, I find and rule a constructive trust to be established by the plaintiff for the defendant such that upon the conveyance of Lot A to the plaintiff, the defendant would be given a right of first refusal upon the sale of Lot A and an additional one-half acre of property from the plaintiff upon the partition of the Bog Lot. Such partition shall be divided equally between the plaintiff and the defendant and thereupon, the plaintiff shall convey one-half acre from his portion to the defendant. This conveyance shall not be made such as to render the plaintiff's Lot A nonconforming.

This agreement appears to be acceptable to the plaintiff, and the defendant has admitted that one of the possible arrangements involved being given an equivalent value in land from the Bog Lot. The defendant's assertions of express and resulting trusts are invalid in that sufficient facts have not been introduced into evidence such as to meet the necessary requirements for each specific type of trust. I further find and rule that the defendant's claim to an improved present day value for her one-half interest in an unimproved Lot A conveyed in 1978 is not a proper measure of compensation and would not be equitable. The terms of the constructive trust as set forth above stand, and the defendant's counterclaim that she be declared a one-half owner of Lot A is hereby denied.

The plaintiff has raised the statute of limitations as a defense to a constructive trust. G.L. c. 260, §2 provides that "actions of contract, . . . founded on contracts or liabilities, express or implied, . . . shall . . . be commenced only within six years next after the cause of action accrues." I find and rule that the cause of action began in 1985 upon discussions held after the death of the uncle when the defendant first began to question the plaintiff as to the existence of a trust in order that she could prepare a will to take care of her children. As the counterclaim was filed on May 13, 1987, it has been brought within the applicable statute of limitations. Brodeur v. American Rexoil Heating Fuel Company, Inc., 13 Mass. App. Ct. 939 , 940 (1982).

Massachusetts General Laws chapter 241, §2 requires that a petition to partition be brought exclusively in the Probate Court, and accordingly, should the defendant wish to effectuate the partition, she must bring such an action in the Plymouth Probate Court.

Judgment accordingly.

exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] All instruments referred to herin are recorded at this registry.