This is an appeal pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 40A, §17 by Livingston Wright, Jr. from the denial by the defendant Board of Appeals of Marshfield (the "ZBA") of a variance from the frontage provisions of the Marshfield Zoning By-Law which require a distance on a street of at least 125 feet in an R-1 District where the locus is situated while the locus has a frontage of only 20 feet.

A trial was held on December 28, 1987 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. The plaintiff and Joan Palsson, an Assistant Assessor's Appraiser for the Town, testified as witnesses for the plaintiff, and no witnesses were called by the Zoning Board of Appeals. Seven exhibits were admitted into evidence by stipulation, and three chalks were filed for the assistance of the Court. All exhibits are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

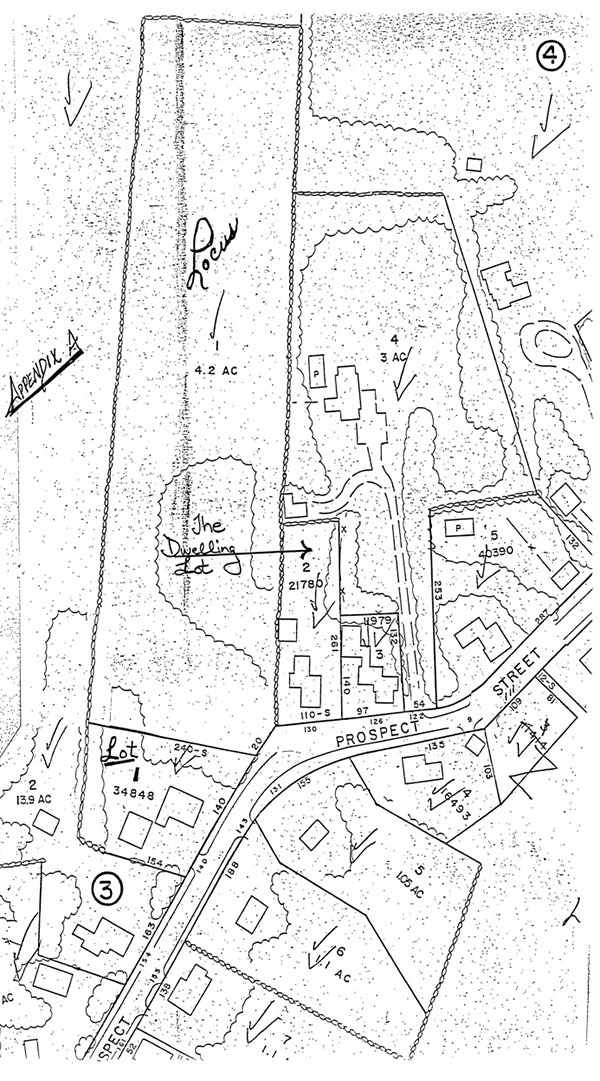

1. The locus is a parcel of vacant land situated on the northerly side of Prospect Street; it has, as already stated, a frontage on the street of only twenty (20) feet, but its area is 4.2 acres.

2. Article Five, Section 1a of the provisions of the Marshfield Zoning By-Law in effect in 1968 required that in an AA District, where Prospect Street was situated, no structure was to be erected on a lot containing less than 150 feet in frontage "at the building line of the widest part of the building" (Exhibit No. 1).

3. A new Zoning By-Law thereafter was adopted on June 12, 1972 and has been successively amended. The locus on the north side of Prospect Street now is situated in a so-called R-1 District in which there is a requirement that there be minimum lot width and frontage of 125 feet.

4. The current Zoning By-Law defines lot frontage as "[t]he total distance along a street line from one front lot corner to the other." Lot width is defined as "[t]he distance between the side lot lines as measured parallel to the front lot line, at the rear building line and at all points between" (Exhibit No. 3).

5. Members of the plaintiff's family have owned properties in the vicinity of locus at least as far back as his great grandfather who was a village blacksmith. The plaintiff testified that the locus formerly was part of the property on which his great grandfather had his blacksmith shop and which now appears as Lot 1 in Block 3 of the sheet of the Marshfield Assessors' Map marked Chalk C.

6. The plaintiff acquired title to the dwelling lot which adjoins locus on the east (the "dwelling lot") by a deed from F. Hazel MacGregor, dated February 1, 1950 and recorded with Plymouth Deeds Book 2132, Page 492. The plaintiff had grown up in this house which originally was owned by his grandfather with the plaintiff's father succeeding him as owner. Livingston Wright, Sr., the plaintiff's father, ultimately conveyed the property to Ms. MacGregor from whom plaintiff acquired title in 1951. Appendix A, a composite of two Marshfield Assessors Maps (El8 marked Chalk B and E17 marked Chalk A), is attached hereto and shows the locus, Lot 1 and the dwelling lot.

7. The plaintiff acquired title to the locus by inheritance from his father who died in 1964. So far as appears, the chains of title to each of the properties, that is, the locus and the dwelling lot, are disparate, and they never were owned in common until the plaintiff inherited the locus, nor does it appear that they ever were used in common.

8. The plaintiff conveyed the adjoining Prospect Street property, the dwelling lot, to John W. Buckley and wife, by deed dated November 23, 1968 and recorded with said Deeds Book 3486, Page 548 (Exhibit No. 5). However, there had technically been common ownership of the locus and the dwelling lot by the plaintiff during the period from 1964 to 1968, although, as stated above, it does not appear that they had been owned in common previous to 1964. The description in the deed out apparently is the same as in the deed to the plaintiff since the former refers in the title reference to "being the same premises conveyed to me by deed of F. Hazel MacGregor."

9. The frontage of the locus on Prospect Street is less than the 40 feet which would be required by the Planning Board should the plaintiff seek to construct a subdivision way into the lot to afford frontage thereon required by the By Law although the Planning Board may in the exercise of its discretion waive this requirement. G.L. c. 41, §81R.

10. The terrain of the lot is such that a subdivision may be impractical since the land rises from Prospect Street for some distance and then about one-half way down the length of the lot the land drops off. The resulting hollow tends to be damp in the spring time. There have been unsuccessful percolation tests.

11. The Zoning Board of Appeals denied the variance on the grounds that the plaintiff had subdivided the land which he owned in the 1960's with a sale of the lot on which there was a dwelling, that the nonconforming lot was the result of the action taken by the plaintiff, and that when the lot was subdivided, the two lots created were substantially more non-conforming than the original parcel. The ZBA further found that "the soil conditions, shape or topography of the land are not unique, being relatively indistinguishable from the rest of the area and that no unique conditions and circumstances were found which do not apply to neighboring lands" (Exhibit No. 7).

12. The present Marshfield Zoning By-Law (Exhibit No. 3) sets forth in part in Section 10.11 substantially the same provisions for the grant of a variance as are mandated in G.L. c. 40A, §10. There are additional provisions in Section 10.11, however, which do not appear in the statute and the validity of which is presumed for the purposes of this decision. They are as follows:

Before any variance is granted, the Board must find all of the following conditions to be present:

1. Conditions and circumstances are unique to the applicant's lot, structure or building and do not apply to the neighboring lands, structures or buildings in the same district.

2. Strict application of the provisions of this Bylaw would deprive the applicant of reasonable use of the lot, structure or building in a manner equivalent to the use permitted to be made by other owners of their neighborhood lands, structures or buildings in the same district.

3. The unique conditions and circumstances are not the result of actions of the applicant taken subsequent to the adoption of this Bylaw.

4. Relief, if approved, will not cause substantial detriment to the public good or impair the purposes and intent of this Bylaw.

5. Relief, if approved, will not constitute a grant of special privilege inconsistent with the limitations upon properties in the district.

13. The locus has been assessed as a building lot for many years, most recently at a valuation of more than $50,000, but after notice to the assessors from the ZBA that it was not a building lot, the assessment was reduced in fiscal 1986.

In the case of Guiragossian v. Board of Appeals of Watertown, 21 Mass. App. Ct. 111 , 114-115 (1985), the Appeals Court pointed out that there were certain general principles governing review by the Courts of the decisions made by local zoning boards in granting variances. Firstly, the trial court justice hears the matter de novo and determines the legal validity of the Board's decision upon the facts which the Court has found. Secondly, no one has a legal right to a variance and they are to be sparingly granted. Thirdly, at the hearing in the Trial Court the person seeking the variance must prove that each of the statutory requirements has been met and that the variance is justified. Each of the elements must be shown as the statutory language is conjunctive, not disjunctive. Finally, it is rare, if not impossible, for a trial court to grant a variance when the Board has not done so, at least in the absence of a legally untenable ground for denial of the variance or a decision clearly arbitrary and capricious. Bruzzese v. Board of Appeals of Hingham, 343 Mass. 421 (1962). Geryk v. Zoning Appeals Board of Easthampton, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 683 (1979). There are many cases in the Appeals Court where plaintiffs found themselves in the same predicament as Mr. Wright; the facts in reported decisions showing common ownership of two adjoining parcels of land, a change in zoning and a sale of a portion of the property thereafter, with the landowner ultimately discovering that he had been left with a nonconforming parcel. These cases almost uniformly hold that a conveyance after a change in zoning bars the applicant from the grant of a variance. Raia v. Board of Appeals of North Reading, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 318 , 322, (1976). They are distinguishable here to the extent that the zoning was changed after the conveyance, not by increasing the frontage requirements which indeed were lessened, but by providing for mandated frontage and width to discourage pork chop-lots. The reported cases also establish that lack of frontage alone is an insufficient reason for a variance. Warren v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Amherst, 383 Mass. 1 (1981); See McCabe v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Arlington, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 934 (1981) (where shape and size were confused).

There are, however, certain exceptions to these general rules. In Paulding v. Bruins, 18 Mass. App. Ct. 707 (1984) there were significant other factors which entitled the landowner to a variance with the lot being unbuildable without it and having an unusual shape which differed from most of the lots in the zoning district. In addition, the lot was larger than most of the others in the neighborhood, and the topography was such as would support a driveway.

There seems to be one significant difference in the present case from many of the decided cases which the parties have not emphasized and which appears to the Court to be important. The provisions applicable to the conveyance by the plaintiff of the adjoining lot on which there was a dwelling were those in effect in 1968; i.e., the application of the zoning by-law in effect in 1968 is critical. At that time the zoning by-law was structured in terms of frontage "at the building line at the widest part of the building". It is impossible to tell on the record before the Court how properly to apply this provision to the locus since the set back provisions are not before the Court. It also is unclear whether this refers to the actual location of the building to be constructed, or to the width at the minimum set back or such further point as hit the widest part of the building. In either case, additional evidence is needed. [Note 1] If in fact the locus were conforming after the conveyance of the dwelling lot and only became non-conforming after the adoption of the 1972 By-Law, then it is the provisions of G.L. c. 40A, §6 which afford guidance. This section is singularly unhelpful in the present case, however, since to be applicable the non-conforming lot needs at least 50 feet of frontage which the locus does not have. As to any grandfather clauses in the local zontng by-law, the record is silent. In any event, the ZBA appears to have focused on the 1972 version of the zoning by-law rather than the one in effect at the time of the conveyance out, and to that extent there is an error of law in its decision. The applicable legal doctrine is harsh in cases like the present, but there are several factors here which the ZBA may wish to consider in evaluating the 1968 deed. Among these are the large area of the lot, its historical background, the short term unity with the dwelling lot only by the historical accident of inheritance, the background of the dwelling lot as a separate piece, the lapse of many years since the conveyance, the narrow entrance to the locus from the street, the preponderance of clay on the locus, and the unusual topography. A consideration of all these elements in the light of the language of the 1968 by-law may well lead to the conclusion by the ZBA that there are considerations affecting the locus but not applicable to the neighboring lands so that relief can be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without impairing the purposes and intent of the by-law. However, this is not a decision which the Court properly can make without affording the Zoning Board of Appeals an opportunity to reconsider the case in the light of the provisions of the 1968 Zoning By-Law. I, therefore, annul the decision of the Zoning Board of Appeals and remand the case to it to hear the evidence relating to the nature of the lot and the statutory provisions set forth in Section 10 in the light of the provisions of the Zoning By-Law applicable in 1968 when the conveyance was made and which focus not on the street frontage but on the lot width.

The plaintiff, of course, is not without remedy. The Planning Board has authority to waive the requirements for a way within a subdivision, and appellate courts previously have suggested this as a way to afford relief to a plaintiff caught in the horns of the large area, little frontage dilemma. See Arrigo v. Planning Board of Franklin, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 802 (1981) rev. den. 385 Mass. 1102 (1982); Gordon v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Lee, 22 Mass. App. Ct. 343 , 351-352 n. 8 (1986).

Judgment accordingly.

LIVINGSTON WRIGHT, JR. vs. BOARD OF APPEALS OF THE TOWN OF MARSHFIELD: JON P. DEVINE, ELLIN L. LEONARD, WILLIAM M. MacMULLEN, JR., JOHN J. MAHONEY and CAROL A. CHELI, as they are members thereof.

LIVINGSTON WRIGHT, JR. vs. BOARD OF APPEALS OF THE TOWN OF MARSHFIELD: JON P. DEVINE, ELLIN L. LEONARD, WILLIAM M. MacMULLEN, JR., JOHN J. MAHONEY and CAROL A. CHELI, as they are members thereof.