The complaint in this matter was filed under G.L. c. 185, §114. The plaintiffs allege that their property, shown as Lot 12 on Land Court Plan No. 24647A, registered with the Fall River District of the Land Court [Note 1] has the benefit of a 50 foot easement as noted on their Certificate of Title No. 2028, over abutting Lot 34 (a portion of former Lot 27) shown on Land Court Plan No. 24647F and presently owned by the defendants Souza. Said easement is not noted on the Souzas' Certificate of Title to said Lot 34. The plaintiffs seek to have the easement noted on the defendants' certificate. The defendants relying on certain sections of G.L. c. 185 deny the existence of the easement.

A trial was held on September 8, 1987 at the Land Court. Witnesses were the plaintiffs, the defendant Milton Souza and Norman Zalkind, common grantor to both the plaintiffs and the defendants. Fifteen exhibits were introduced into evidence, all of which are incorporated herein for purposes of any appeal. A view of the property involved was taken in the presence of counsel.

On all of the evidence, I find and rule as follows:

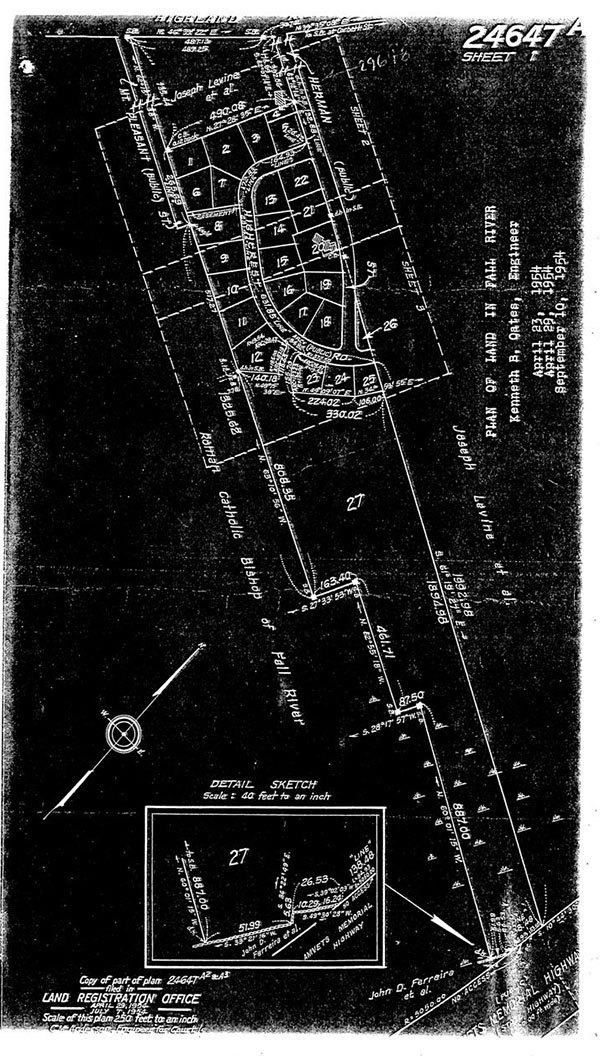

1. In 1954 Joseph Levine and Norman Zalkind subdivided a large tract of undeveloped land in Fall River and registered their title thereto. This Court issued them original Certificate of Title No. 1343. The original decree plan no. 24647A consisting of three sheets is registered with the certificate in Book 7, Page 339. A copy of sheet 1 of said plan is attached hereto for reference.

2. As shown on said plan, Lots 12 and 23 are bounded northerly by the southerly line of Highcrest Road. Their northeasterly and northwesterly boundaries, respectively, are more or less parallel and are separated by a strip or neck of land being a portion of Lot 27. As it divides Lots 12 and 23, this strip is fifty feet in width except at its junction with Highcrest Road where it flares out to approximately eighty-five feet.

3. The developers originally intended that this strip be used as an access to a possible further subdivision of Lot 27.

4. By deed dated June 16, 1965 registered as Document No. 7086, Levine and Zalkind conveyed Lot 12 on said plan to the plaintiffs, Carl and Irma Feldman. The deed contains the following language pertinent hereto:

NORTHEASTERLY AND EASTERLY: By an arc ... said arc forming the Southwesterly junction of said Highcrest Road, and an unnamed fifty foot wide way, on Lot 27, on the Plan hereinafter mentioned: (Plan 24647A).

Together with the right, in common with the grantors, their heirs and assigns, and others having a right thereon, and all persons entitled by, through or under them, or any of them, to use for all purposes for which streets or ways are ordinarily used, the proposed 50 foot wide way shown on said Plan adjoining the Northeasterly line of said lot 12, but the grantors do not assume any obligation to open or maintain said way for such use, provided, however, and the easement hereby granted in said proposed way shall continue only until said way is dedicated and taken or accepted by said City of Fall River as a public way, for public use as a city street.

The deed was subject to certain restrictions.

5. On the same date in Document No. 7087, approving plans (required under one of the above "restrictions") for the plaintiffs' proposed home, Levine and Zalkind refer to the location as

... the lot located at the Southwesterly corner of Highcrest Road, and a private way leading to Lot No. 27 in Fall River, Massachusetts, being Lot No. 12....

6. Subsequent thereto the plaintiffs were issued Certificate of Title No. 2028 dated June 17, 1965 which certificate bears the notation:

Said land has the benefit of the right of way as set forth in a deed from Joseph Levine et al to Carl Feldman et al dated June 16, 1965 filed and registered as Document #7086.

7. The plaintiffs' deed of Lot 12 was noted on the memorandum section of Original Certificate of Title No. 1393, which was cancelled as to Lot 12. For reasons unknown no notation of the easement was made on this certificate.

8. Between 1965 and 1966, the plaintiffs constructed a single family home on Lot 12. From a view of the premises, it would appear that the house is a "split level" with a two car garage in the lower level facing and exiting onto Highcrest Road via the easement, a portion of which was paved by the plaintiffs. The house is apparently built in accordance with the approval referred to in paragraph 5 above. Because of the topography of the lot, the only practical access to the garage is via the easement.

9. In 1974, Levine and Zalkind subdivided Lot 27 into Lots 33 and 34 as shown on Land Court Plan No. 24647F. Lot 34 along with Lots 9, 10 and 11 on 24647A were conveyed to Norman Zalkind as Trustee of Highland Village Trust. Lot 34 abutted the plaintiffs' Lot 12 on two sides and had frontage on Highcrest Road via the strip or neck shown on the "A" plan. The lot appears suitable for no more than one dwelling. At or before this time, Levine and Zalkind abandoned as impractical any thought of dividing Lot 27 into more than two lots. There was no mention of the plaintiffs' easement in the deed to Zalkind, Trustee, nor is there any mention of it in the Zalkind certificate.

10. Sometime around 1983, the defendants Milton and Emily Souza acquired Lot 9 and a portion of Lot 10 on the "A" plan (this lot is Lot 35 on the "G" plan) and constructed a single family residence thereon. They resided here until the summer of 1987. During this time, Mr. Souza observed the plaintiffs' asphalt driveway as it extends into Lot 34 (former Lot 27); he also became familiar with the situation of the plaintiffs' house on the lot.

11. On March 14, 1986, the Souzas signed a purchase and sale agreement, agreeing to purchase Lot 34 from Norman Zalkind, Trustee. The agreement requires the seller to convey "good and clear record and marketable title, free from all encumbrances ... and all easements, restrictions and rights of way, ... provided they do not substantially interfere with the intended use of the premises."

12. Sometime during the last week in March, at the defendants' direction, a survey was made of Lot 34. Stakes were placed along the boundary line, which indicated that the plaintiffs' driveway was in part on Lot 34.

13. While there is conflicting testimony as to conversations between Mr. Feldman and Mr. Souza during the period after which the stakes were set and prior to the closing on the property, I find most credible Mr. Feldman's testimony that a day or so after observing the stakes, he had a conversation with Mr. Souza at which he informed Souza that his driveway was on an easement or right of way given to him when he purchased the property. Such reaction is entirely in accord with what one would expect of a reasonable person upon the discovery of surveyors' stakes on what he believed to be his property. Accordingly, I find that sometime in late March, the defendants were put on notice of the existence of the Feldman right of way.

14. On two occasions prior to the closing, Souza specifically asked Zalkind if any easements existed over Lot 34 and was told there were none.

15. The Souzas acquired Lot 34 on April 22, 1986 by deed registered as Document No. 15744. Sometime thereafter they were issued Transfer Certificate of Title No. 4282. Neither the deed nor the certificate have any notation of Feldman's easement. In September 1986, the Souzas mortgaged the property to Bank of New England, N.A. and shortly thereafter constructed a home thereon. The easement is not mentioned on the mortgage.

The issue before the Court is whether or not the easement noted in the plaintiffs' deed and on their Certificate of Title is binding on the defendants' land when neither their deed or certificate nor their predecessors' deed or certificate contain any such notation.

Pertinent sections of C. 185 are:

§46 Every plaintiff receiving a certificate of title in pursuance of a judgment of registration and every subsequent purchaser of registered land taking a certificate of title for value and in good faith, shall hold the same free from all encumbrances except those noticed on the certificate,

§58 Every conveyance, lien, attachment, order, decree, instrument or entry affecting registered land, which would under other provisions of law, if recorded, filed or entered in the registry of deeds, affect the land to which it relates, shall, if registered, filed or entered in the office of the assistant recorder of the district where the land to which such instrument relates lies, be notice to all persons from the time of such registering, filing or entry.

§59 ... All interests in registered land less than an estate in fee simple shall be registered by filing with an assistant recorder the instrument which creates or transfers or claims such interest, and ... by a brief memorandum thereof made by an assistant recorder upon the certificate of title signed by him....

§62 The production of the owner's duplicate certificate, whenever a voluntary instrument is presented for registration, shall be conclusive authority from the registered owner to the recorder or an assistant recorder to enter a new certificate or to make a memorandum of registration in accordance with such instrument, and the new certificate or memorandum shall be binding upon the registered owner and upon all persons claiming under him, in favor of every purchaser for value and in good faith.

As a general rule, a statute should be construed in a fashion which promotes its purpose and renders it an effectual piece of legislation in

harmony with common sense and sound reasons, Worcester Vocational Teachers' Ass'n. v. City of Worcester, 13 Mass. App. Ct. 1 (1982). Had the dictates of the statute been properly followed in this instance, there would be no controversy. In this instance, the plaintiffs presented a deed with an easement together with the grantor's Certificate of Title to the proper office for registration. In due course a new certificate was prepared for and delivered to the plaintiffs referring to the easement. A notation was made on the grantor's certificate indicating the conveyance of Lot 12 but for reasons unknown, there was no notation of the easement noted on this certificate, as required by §§59 and 62. In such instances, where the law has not been followed, through no fault of either party, common sense and sound reasoning must far outweigh literal interpretations.

Unfortunately, the omission of an encumbrance is not unique. When the holder of the servient certificate has actual notice of the encumbrance, it is well established that he does not receive indefeasible title against such interests. Any other reasoning would render meaningless the provision of §46 that one acquires registered land free from unregistered encumbrances only if he is a purchaser in "good faith." Killam v. March, 316 Mass. 646 , 651 (1944). While the facts of the Killam case differ from those herein in that there was mention of an encumbrance in the Killam sales contract, in the present case the defendant had notice by his own observations of the existence of the plaintiffs' driveway on part of the right of way. In addition thereto, he was informed of the existence of such easement by the plaintiff well before the property was purchased, circumstances which were held to be adequate notice to render an unregistered easement valid in Andover v. DeVries, 326 Mass. 127 , 131-132 (1950). In the face of such information, the defendant chose to rely on the seller's representation and a search of the record limited to the seller's certificate. While such search would be adequate under normal circumstances, with the aforementioned information it would be less than prudent not to review the plaintiffs' certificate which was readily available at the registration office.

Without deciding whether or not the defendants' action amounted to a lack of good faith, it is obvious that the defendants can acquire no greater rights than the grantor had. An oversight in the land registration office cannot confer or extinguish existing registered rights even though they appear on only the dominant certificate.

The defendants' argument that the original grantors abandoned the easement has no bearing on the plaintiffs' rights. The plaintiffs have been and are using the easement for the purposes granted, namely, access to and from Highcrest Road.

In consideration of the foregoing, I find and rule that the plaintiffs, Carl and Irma Feldman, their heirs and assigns have a right in common with the defendants Souza to use, for all purposes for which streets or ways are ordinarily used, the strip of land from 50 feet to 84.42 feet in width abutting the northeasterly side of Lot 12 as shown on Plan No. 24647F as filed in the land registration office. A notation of such easement is to be placed on the defendants' certificate, no. 4282, registered with the Fall River Registry District in Book 22, Page 333.

The plaintiffs and defendants have requested various rulings of law and findings of fact. Inasmuch as I have made such findings and rulings of my own as I consider pertinent, I decline to make any others.

Judgment accordingly.

CARL FELDMAN and IRMA FELDMAN vs. MILTON SOUZA, EMILY SOUZA and BANK OF NEW ENGLAND, N.A.

CARL FELDMAN and IRMA FELDMAN vs. MILTON SOUZA, EMILY SOUZA and BANK OF NEW ENGLAND, N.A.