The plaintiff, Edward Lyons, Trustee of Vista Realty Trust, d/b/a Vista Realty ("Lyons"), commenced this action seeking judicial review, pursuant to G.L. c. 41, § 81BB, of a decision of the Planning Board of the Town of Sharon ("The Board") disapproving the plaintiff's definitive subdivision plan of his eleven acre parcel in Sharon ("the locus"). Upon the plaintiff's motion, the trial was bifurcated so that the issue of whether the Board abused its discretion in failing to grant a certain waiver would be reserved until the Court entered its decision and order as to all other issues in this action.

A trial was held extending over five days, at which a stenographer was sworn to take and transcribe the testimony. The Court in the presence of counsel took a view of the locus. Five witnesses testified and twenty exhibits were accepted into evidence. Said exhibits are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. Based on all of the evidence I find and rule as follows:

FACTS:

1. Edward Lyons, Trustee of Vista Realty Trust d/b/a Vista Realty ("Lyons"), is now and was since October 1, 1984 the record owner of a parcel of land comprising eleven (11) acres, more or less, located in the Town of Sharon, Massachusetts (the "locus").

2. Thomas C. Houston, Marilyn Z. Kahn, Martin A. Levitt, Evelyn W. Suchecki and George B. Bailey were at the time of the decision appealed from, the members of the Planning Board of the Town of Sharon (the "Board").

3. To the east and south of and adjacent to the locus are lands owned by the Town, a majority of which Town lands are comprised of vegetated wetlands, a brook and two ponds.

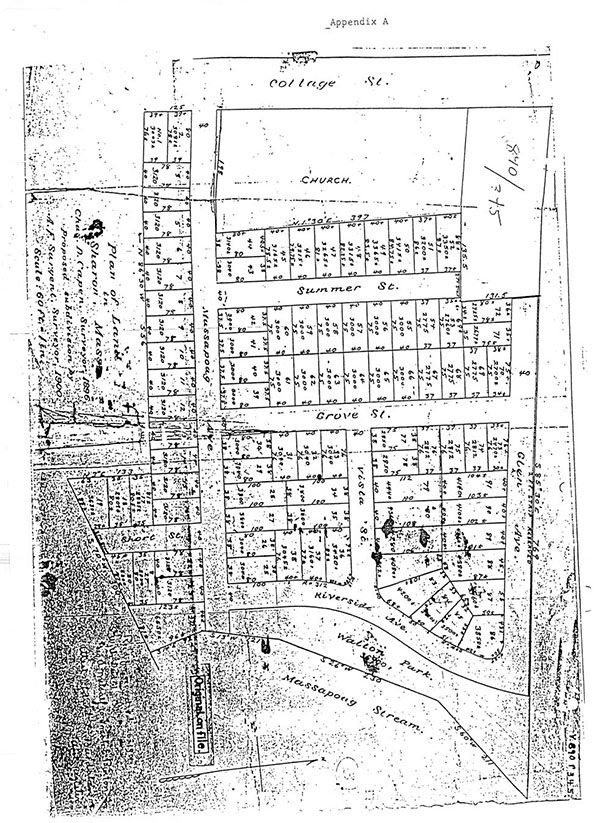

4. George A. Metcalf conveyed to Frank E. Buxton by deed dated February 19, 1901, recorded in Norfolk Deeds on February 26, 1901, Book 890, Page 345, parcels 1, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19 and 76-85 inclusive, shown on a plan recorded with the deed entitled "Plan of Land in Sharon, Mass. Chas. D. Capen, Surveyor, 1896. Proposed subdivision by A. F. Sargent, Surveyor, 1900. Scale: 60 Ft. = 1 In. (1900 plan)." [Note 1] Recorded on the same date was a plan entitled "Chas. D. Capen, Surveyor, 1896. Plan by B.W. Capen, 1900."

5. The 1900 plan does not accurately reflect the boundaries of the locus. The discrepancies between that plan and the locus are caused by a surveying error wherein the southern most boundary of the locus incorrectly shows a bearing of N86°30'W. When the courses and distances on the 1900 plan are plotted they do not close. If the course on the southern most boundary had read N86° 30'E, the lines on the plan would close and the plan would more accurately reflect the actual boundaries of the locus. There was less land in the 1901 subdivision than was depicted on the 1900 plan, with the result that all of the parcels and roads could not collectively be laid out on the ground as depicted on the 1900 plan.

6. On March 26, 1901, Frank E. Buxton conveyed the same parcels he acquired from Metcalf to Harriott M. Kendall, recorded in Norfolk Deeds, Book 890, Page 347.

7. The deeds by which Metcalf conveyed to Buxton, Buxton conveyed to Kendall, and from whom the Town acquired title to parcels 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14, described each parcel as bounded "northerly by Massapoag Avenue, forty feet, easterly by [an adjoining] lot on said Plan, seventy-eight feet, southerly by land of owners unknown, as the wall now stands, forty feet and westerly by [an adjoining] lot.....on said Plan, 78 feet. Containing 3,120 square feet." The stone wall referred to in those deeds exists and its location is ascertainable today. [Note 2] Massapoag Avenue was never laid out and there is nothing on the ground to indicate where it is located.

8. On October 16, 1905, the Town of Sharon acquired by tax title said parcels 1, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19 and 76-85 (the Town parcels). The Town still owns all of the aforesaid parcels.

9. Subdivision control, pursuant to G.L. c. 41, §§ 81A-81J, became effective in the Town of Sharon in 1944.

10. On or about August 31, 1984 Lyons filed with the Board a Preliminary Subdivision Plan under G.L. c. 41, § 818 (the "preliminary plan"), for the subdivision on his eleven acre parcel into ten (10) lots, and gave notice of submittal to the Town Clerk.

11. The applicable Land subdivision Rules and Regulations for the Town of Sharon Planning Board are the 1981 Rules and Regulations (the Board's rules).

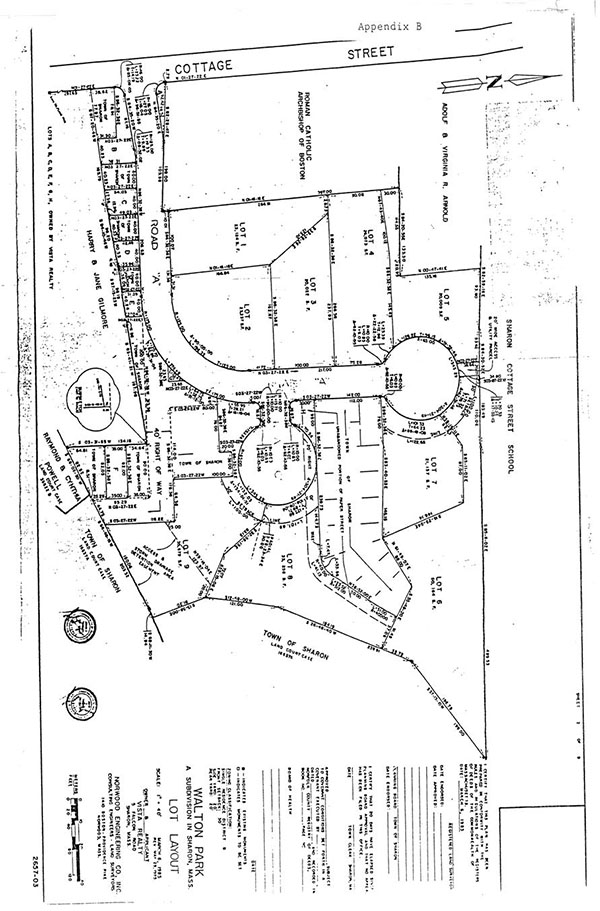

12. On November 7, 1984, the Board granted approval of the preliminary plan for nine (9) lots.

13. On March 6, 1985 Lyons submitted to the Board a Definitive Subdivision Plan under G.L. c. 41, § 41T, proposing the subdivision of his land in Sharon into nine (9) lots (the "definitive plan"), with revisions on May 29, 1985, and gave notice of submittal to the Town Clerk. [Note 3]

14. As shown on Appendix B, the definitive plan depicts the subdivision as being partially bounded on the west by Cottage Street and also depicts Cottage Street as being the sole means of access and egress to and from the subdivision. The subdivision is additionally bounded on the west by land of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston ("Church land"). The access and egress to and from the subdivision consists of an irregular, saw-tooth shaped strip of land, which varies in width from approximately 50' to approximately 40' and runs in length for approximately 200'. That strip is bounded northerly by the Church land and southerly by both Town land and the land of another.

15. Hearings were held by the Board in connection with the definitive plan on April 17, April 22, June 5, June 19, July 2 and July 17, 1985.

16. On July 17, 1985 the Board disapproved the definitive plan for the following stated reasons:

1. The minimum width of the right of way required by 4.2.3.1 is 50 ft. . . '[T]he minimum required right of way width for proposed Road "A" is 50 ft because Road "A" is subject to the subdivision control law and changes in it'--even 'where the northern boundary of ["Massapoag Avenue"] is land of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston' and the southern boundary is land owned by the Town.' Further. . .the Town owned parcels fronting on the southerly side of proposed Road "A" actually extend substantially into the proposed right of way. Upon adjusting the southern side line of the proposed right of way to coincide with the actual location of the northern boundaries of the Town parcels, the proposed right of way would be significantly narrower (i.e. less than 20 ft. wide) than the 50 ft. minimum width required by 4.2.3.

2. The proposed profile grade line of Road A varies significantly (approximately 6 feet) from existing ground between Stations o+oo and 3+oo. The side slopes of the required embankments would encroach approximately 12 feet onto the land of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston and 12 additional feet onto Town owned parcels.

3. The plan proposes to discharge stormwater from the stormwater detention area across a lot line onto a parcel owned by the Town of Sharon (Land Court Case No. 16537A). The volume of this discharge was identified by the Applicant's engineer to be approximately 4,300 gallons per minute in revised calculations dated May 20, 1985. No drainage easement is provided as required by Section 4.5.3. The plan does not indicate how the stormwater will be conveyed to Massapoag Brook or what course the discharge will take as required by Section 3.3.2.15.

17. The requirement of a 50' minimum road width was first enacted into the Board's rules in 1968.

18. Prior to that date, the maximum required road width for right of ways for minor streets was 40'.

19. Under current zoning laws, buildings cannot be erected on the Town parcels bounded on the north by Massapoag Avenue (Road

"A").

20. Sheet 6 of the definitive plan states: "Slope Easement To Be Obtained From Abutter Or Retaining Wall Design To Be Forth Coming."

21. The definitive plan provides for drainage from the subdivision to be collected in a retention basin in the southeasterly section of the property and then released through a weir, approximately 14' within the boundary of the subdivision. This system is referred to as a point source of discharge. The system also incorporates an undetermined amount of sheet flow. All such drainage discharges onto adjacent Town land. Those Town lands consist primarily of vegetated wetlands.

22. Sheets 7 and 8 of the definitive plan use contour lines to depict the course of drainage discharge. All contour lines are primarily shown within the subdivision.

23. The nearest primary water course is Massapoag Brook, which is approximately 140' from the last contour lines.

24. The rate of runoff after development of the subdivision would be approximately equal to the rate of runoff before development.

25. Lyons presented no evidence to the Board that drainage onto the Town wetlands was "satisfactory or permitted" by the Town.

Lyons is appealing the decision of the Board, wherein Lyons' definitive plan was disapproved for the three previously stated reasons, namely; road width, embankments, and drainage.

When approval of a subdivision plan is denied, the applicant is entitled to appeal the planning board's decision to the Land Court, which "shall hear all pertinent evidence and determine the facts, and upon the facts so determined shall annul such decision if found to exceed the authority of such board, or make such other decree as justice and equity require." G.L. c. 41, § 81BB. The Court will conduct a de novo hearing, and on the facts found by the Court, rule upon the validity of the determination of the planning board. Rettig v. Planning Board of Rowley, 332 Mass. 476 , 479 (1955). The Court must confine its review to the reasons given by the Board in its decision for disapproval of the definitive plan. Fairbairn v. Planning Board of Barnstable, 5 Mass. App. 171, 173 (1977). A planning board should approve a plan when it complies with the recommendations of the board of health and with the reasonable rules and recommendations of the planning board. Baker v. Planning Board of Framingham, 353 Mass. 141 , 144 (1967). The burden for showing that the planning board exceeded its authority rests on the developer. Fairbairn, 5 Mass. App. at 173.

Right Of Way Width

The first basis given by the Board for the disapproval of Lyons' definitive subdivision plan was that "Road A" did not meet the 50' minimum width requirement as set out in the Board's rules. The two reasons cited by the Board for Road A not meeting this requirement were that one, Road A, as depicted on the plan, varies in width from 50' to 40', and two, that the Town parcels abutting the subdivision on the south actually extend substantially into Road A, such that Road A would at points be less than 20' in width.

The locus was originally subdivided into ninety-one parcels as shown on the 1900 plan. (See App. A). Certain parcels were sold in 1901 to another, and those same parcels were acquired by the Town of Sharon by way of tax titles in 1905. The subdivision control law of Sharon became effective in 1944. Although Lyons concedes that those portions of Road A abutting only his parcels would be subject to the 50' minimum width requirement, he argues that those portions of Road A abutting the Town parcels would fall within the provisions of G.L. c. 41 § 81FF which provides, inter alia, that:

So far as land which has not been registered in the land court is affected by the subdivision control law, recording of the plan of a subdivision in the registry of deeds before the subdivision control law was in effect in the city of town in which the subdivision was located shall not exempt that land within such subdivision from the operation of said law except with respect to lots which had been sold and were held in ownership separate from that of the remainder of the subdivision when said law went into effect in such city or town, and to rights of way and other easements appurtenant to such lots....

He argues therefrom that where Road A abuts the Town parcels, that the 40' right of way shown on the 1900 plan controls over the 50' minimum width requirement. The Board contends that the above referenced provisions of § 81FF are intended to protect individuals

who purchased parcels in reliance on a recorded subdivision plan, and therefore, that only those individuals and not the developer, are entitled to the protection provided by § 8lFF. The Board further contends that the Town is under no obligation to seek the relief provided under § 81FF for the benefit of the plaintiff.

In Toothaker v. Planning Board of Billerica, 346 Mass. 436 , 439 (1963), the Supreme Judicial Court held that the provisions of

§ 81FF at issue herein "relate only to each lot sold before the subdivision control law became applicable and refer to the substance of the rights of way or easements appurtenant thereto. The words of the statute do not exempt the owners of the other lots from compliance with the subdivision control law." The Court went on to hold that § 81FF "does not fix the location or extent of the rights of way appurtenant to lots sold before the subdivision control law became applicable. Those rights are determined by the private grants." Id. at 439. The Court noted in dicta that "the owners and the planning board must so apply the law that the existing exempt rights of way of the lots separately owned . . . are not destroyed or substantially limited or interfered with." Id. at 440. I infer from this language that the protection provided by § 81FF may, but need not be, affirmatively sought by the owners of the separately owned lots, but rather, that the developer and the planning board must apply § 81FF to protect the rights of the owners of those lots with respect to the exempt rights of way. To hold otherwise would potentially allow the owners of separately owned lots to utilize the provisions of § 81FF, designed to protect them, offensively against developers. I do not believe that this was the intent of the Legislature in enacting § 81FF. I therefore rule that where Road A is bounded on the north by the Church land and on the south by he Town parcels, that Road A is exempt from the Boards rules regarding road widths and need only be 40' wide. I further rule that where Road A is bounded on one side by the Town

parcels and on the other side by the land of Lyons, that Road A must comply with the 50' minimum road width requirements of the Board's rules. The above two widths are properly reflected on Lyons' definitive plan. (See App. B). Therefore, the Board was incorrect in disapproving the definitive plan on the basis that Road A did not meet the road width requirements at the aforesaid portions of Road A.

In order to determine the validity of the Board's position that Town parcels extend into Road A, I must begin with the initial conveyance of those parcels in 1901. The deed descriptions for the 1901 conveyances of parcels 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 described each lot as bounded "northerly by Massapoag Avenue, forty feet, easterly by [an adjoining] lot on said Plan, seventy-eight feet, southerly by land of owners unknown, as the wall now stands, forty feet and westerly by [an adjoining] lot . . . on said Plan 78 feet. Containing 3,120 square feet." The plan referred to was the 1900 plan. That plan, due to a surveying error wherein the southern most boundary of the locus showed a bearing of N86°30'W instead of the actual N86°30'E, does not accurately reflect the boundaries of the locus. The 1900 plan incorrectly shows the southern most boundary of the Church land and southern most boundary of the locus as being parallel, (See App. A) when in fact those two boundaries are not parallel. The actual position of those boundaries is depicted on Lyons' definitive plan. (See App. B). The deed descriptions for the 1901 conveyances were apparently taken from the 1900 plan. There was, however, not enough land in the original subdivision for parcels 4 and 6 to be bounded on the north by a 40' way. In fact, all of the parcels and roads could not possibly be laid out collectively as depicted on the 1900 plan.

Lyons argues that the stone wall and the 40' way described in the 1901 conveyances are monuments which govern over the courses, distances and computed contents of the parcels at issue for purposes of determining their boundaries. See Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 (1964). This would result in the Town parcels varying in widths to the point that one parcel would only be approximately 4' deep, as opposed to the 78' depth described in the 1901 conveyances. There is no question that the stone wall is a monument which was in existence in 1901, and is in existence today, which serves as the southern most boundary of the Town parcels. The 40' way, depicted as Massapoag Avenue on the 1900 plan and Road A on the definitive plan, however, is a paper street which has never been laid out. There was no evidence introduced to show that there exist any other physical monuments on the ground which might demark the location of the 40' way, in fact, there was direct testimony to the effect that there exist no such monuments to demark the location of the way.

Monuments govern over courses and distances because the later are deemed to be approximations, while the former represent ascertainable locations. See Temple v. Benson, 213 Mass. 133 , 132 (1912). There exists a presumption that the parties intended to convey land to the point which is certain or capable of being made certain. Id. Deed descriptions recited as bounding on land of another may serve as a monument, even though there is nothing visible to mark the line of such land. Hews v. Troiani, 278 Mass. 224 , 229 (1932); Pickman v. Trinity Church, 123 Mass. 1 , 5 (1877). An abutting property line can only serve as a monument when it is capable of being made certain. Applying that rule of construction to this case, the southerly boundary of the Church land is capable of being made certain. The issue then becomes, should that boundary serve as a monument to demark the 40' way, and then by implication, the 40' way would become a monument to demark the extent of the Town parcels bounding southerly of the way. The 1900 plan, which was incorporated into the 1901 conveyances by way of reference, shows an undetermined amount of buffer land between the church land and the 40' way, (See App. A), and therefore, it was not the intent of the parties in the 1901 conveyances that the church land should serve as a monument to demark the 40' way. Further, as stated previously, the parcels and roads depicted on the 1900 plan cannot be laid out in their totality on the ground, so that, the location of the 40' way is no more ascertainable than the location of the Town parcels. Because the location of the 40' way is not capable of being made certain it cannot serve as a monument to demark the boundary of the Town parcels. Lyons has cited two cases, Lemay v. Furtado, 182 Mass. 280 (1902) and Daviau v. Bestourney, 325 Mass. 1 (1949) for the proposition that a paper street is a monument. Neither of these cases stand for that proposition. The Lemay case dealt with the rights of certain individuals in a way created by the words "thence by a way". The Daviau case dealt with the issue of whether a "passageway", which was visible on the ground, could serve as a monument. While under some conceivable set of facts a paper street might be capable of serving as a monument because its location was capable of being made certain, those are not the facts of this case. I therefore rule that the 40' way shown on 1900 plan and referenced in the 1901 conveyances is not a monument for purposes of delimiting the extent of the Town parcls.

Lyons next argues that because the 1900 plan was referenced in the 1901 conveyances, it becomes part of those conveyances for purposes of determining the location of the 40' way, and therefore, the 40' way must run as depicted on the 1900 plan. It is true that a recorded plan referenced in a deed will become a part of that contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of parcels and to determine any rights which were intended to be conveyed. Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 (1945). In this case, however, the 1900 plan does not accurately reflect the area of the locus, and so cannot determine where certain boundaries and ways should, or even can, exist. The only thing that the 1900 plan can do is indicate generally where certain parcels are located and on what parcels the various ways should bound. The deeds are the instruments which will control the rights of the parties, and any uncertainties in the construction of those deeds will be construed against the grantor and in favor of the grantee. See Whitehead, Inc. v. Gallo, 357 Mass. 215 , 219 (1970).

The Town parcels bounding southerly of the 40' way are described in the 1901 conveyances as being 78' deep. The Town parcels were the first parcels conveyed out of the 1901 subdivision, and so, wherever possible, those parcels should be 78' deep with a 40' way. Because the Board is not seeking a determination from the Court as to the actual extent of the Town's rights in their parcels and in the 40' way, the Court will not attempt to establish the precise location of each Town parcel. It is sufficient to rule that parcels, 8, 10, 12 and 14 as shown on the 1900 plan constitute a group of parcels 78' deep and bounding on a 40' way as depicted on the 1900 plan and as described in the 1901 conveyances. This would of course necessitate the 40' way being located more northerly than shown on Lyons' definitive plan. Moreover, it would also require that the 40' way not run in a straight line, but rather, would bend or turn an undetermined amount at the southeasterly corner of the Church land. I therefore rule that Road A, as depicted on Lyons' definitive plan, does encroach on some of the Town parcels, and therefore, the Board acted properly in disapproving Lyons' definitive plan on that ground.

EMBANKMENTS

Subsection 4.2.8.1 of the Board's rules provides as follows:

Embankments within or adjoining the right-of-way shall be evenly graded and pitched at a slope of not greater than two (2) horizontal to one (1) vertical. Where cuts are made in ledge, other slopes may be determined with the approval of the Town Engineer. Where terrain necessitates greater slopes, retaining walls, terracing, fencing, or rip-rap may be used either alone or in combination to provide safety and freedom from maintenance, but must be done in accordance with plans filed with and approved by the Planning Board. Retaining walls shall normally be constructed of stone, with wall thickness at any point not less than one-third (1/3) the depth below retained grade. Whenever embankments are built in such a way as to require approval by the Board, the developer must furnish to the Town duly recorded access easements free of encumbrances for maintenance of the slopes, terraces or retaining walls. All such slopes shall be grassed or planted in accordance with Section 4.6.5.

At trial, Lyons' own expert witness testified that the topography of Road A was such that either slope easements or retaining walls would be required at points along Road A in order to comply with subsection 4.2.8.1. Lyons' definitive plan bears a notation which reads "Slope Easement To Be Obtained From Abutter Or Retaining Wall Design To Be Forthcoming."

Lyons argues that the above notation satisfies the requirements of subsection 4.2.8.1 in that the Board should be required to approve the definitive plan, and, if neither the slope easements nor the appropriate retaining wall designs are forthcoming, then the Board should withdraw its approval. The Board argues that a proposal or promise to comply with subsection 4.2.8.1 does not constitute conformance therewith, and, on that basis alone they were justified in disapproving the definitive plan. The rule explicitly calls for either retaining wall plans to be filed with and approved by the Board or for recorded access easements to be provided to the Board. I therefore rule that subsection 4.2.8.l requires one of the above two submittal requirements as a condition precedent for the Board's approval.

Because Lyons failed to make either submission, I rule that the Board was justified in disapproving the plan on that basis.

LOT DRAINAGE AND SECTION 3.3.2.15 UTILITY PLAN

The third basis for denial of the definitive plan concerned drainage onto adjacent Town lands from the proposed subdivision. The Board found that the definitive plan did not provide the proper drainage easements and did not show how stormwater would be conveyed to Massapoag Brook or what course the discharge would take.

The definitive plan does depict a drainage system within the subdivision. The Board, however, did not disapprove the definitive plan based on the drainage system within the subdivision.

That system culminates at a point source of discharge with a devise for regulating the flow of water. [Note 4] The system is designed so that the rate of runoff from the developed subdivision is approximately the same as before any development of the locus. The point source of discharge is physically in the subdivision. The drainage discharges approximately 14' within the boundary of the subdivision and runs onto and over the Town lands, presumably to Massapoag Brook.

The Board ruled that a drainage easement needed to be obtained from the Town for the system outlined in the definitive plan. The Board's decision cites § 4.5.3 of their rules as requiring such an easement. Section 4.5.3 provides as follows:

Lots shall be prepared and graded in such a manner that development of one shall not cause detrimental drainage on another; if provision is necessary to carry drainage to or across a lot, an easement or drainage right-of-way of a minimum width of twenty feet (20') and proper side slope shall be provided. Storm drainage shall be designed in accord with the specifications of the Board. Where required by the Planning Board or the Board of Health, the applicant shall furnish evidence as to any lot or lots to either Board as necessary that adequate provision has been made for the proper drainage of surface and underground waters from such lot or lots.

The above section clearly concerns drainage between lots within a subdivision. By itself, it cannot be construed to require drainage easments from abutting land owners. The Board argued at trial that if § 4.5.3, § 3.3.2.15 and § 3.3.2.16 are read together, that drainage easements are required when discharge will flow onto and over abutting lands. Section 3.3.2.15 provides that the following shall be provided to the Board, on the proposed plans:

Size and location of existing and proposed water supply mains and their appurtenances, hydrants, street lighting and its appurtenances, fire alarm systems, storm drains and their appurtenances, and easements pertinent thereto, and curbs and curb dimensions, including data on borings and soil test pits, and method of carrying water to the nearest watercourse or easements for drainage as needed, whether or not within the subdivision;

If surface water drains will discharge onto adjacent existing streets or onto adjacent properties not owned by the applicant, he shall clearly indicate what course the discharge will take, and shall present to the Board evidence from the Town Engineer or the owner of adjacent property that such discharge is satisfactory and permitted by public or private ownership of adjacent street or property.

and section 3.3.2.16 provides as follows:

Drainage calculations shall be submitted in a suitable form along with amplifying plans outlining drainage areas within and affecting the subdivision. A plan shall also be submitted showing the route followed by all drainage discharging from the subdivision to the primary receiving water course or other large body of water.

The Board argues that the various provisions of the rules must be read in their complete context and be given a sensible meaning within that context. Board of Selectmen of Hatfield v. Garvey, 362 Mass. 821 , 826 (1973). While this is true, planning board regulations must also be comprehensive, reasonably definite, and carefully drafted, so that owners may know in advance what is or may be required of them and what standards and procedures will be applied to them. Castle Estates, Inc. v. Planning Board of Medfield, 344 Mass. 329 , 334 (1962). This does not mean that imperfect wording is necessarily fatal to a regulation's validity, despite that fact that more lucid regulator language could have been used. See North Landers Corp. v. Planning Board of Falmouth, 382 Mass. 432 , 442 (1981).

The Board's contention that the above three sections read together would require drainage easements from abutters whenever water discharges onto adjacent property would result in a construction of the Board's rules which is impermissibly vague and unenforceable for the following reasons. The first paragraph of § 3.3.2.15 could be construed to be a mandatory requirement for the provision of drainage easements from abutters whenever discharge runs over their land. The second paragraph, however, seems to only require a showing by the developer that drainage onto adjacent land is "satisfactory" to or with the abutter. These two paragraphs conflict with one another. Section 3.3.2.15 does not clearly indicate when or to what extent any drainage easements would be required, and therefore, the standard for when such an easement would be required is not reasonably definite enough for developers to know in advance what is required of them. [Note 5] I therefore rule that this standard is too vague to be enforceable, and therefore, that the Board's 1981 rules cannot be construed to require drainage easements from abutters. That portion of the Board's decision which disapproved the definitive plan based on a lack of drainage easements, therefore, exceeded the Board's authority. In any event, Lyons furnished neither a drainage easement from the Town, nor any evidence that drainage was "satisfactory" to or with the Town.

The final reason given by the Board for disapproval of the definitive plan was that the plan did not indicate how stormwater would be conveyed to Massapoag Brook or what course the discharge would take. The Board only cited § 3.3.2.15 as requiring that information, however, § 3.3.2.16 also requires the provision of that information. Both sections, read together, clearly call for the provision of that information whenever water is discharged from a subdivision.

The definitive plan uses contour lines on sheets 7 and 8 of the definitive plan to show the course of discharge. The Board argues that contour lines are not the proper method of indicating the course of discharge, and, if they are, that the contour lines run only to the approximate boundary of the subdivision, and that Massapoag Brook is approximately 140' from the last contour line, and therefore the course of discharge is not shown to the nearest primary water course. Lyons argues that the plan does show the course of discharge because the Board's own witnesses testified that they were not in doubt as to the course of discharge.

The fact that the Town Engineer and Town Hydrology consultants were aware that drainage from the subdivision would enter Massapoag Brook does not mean that the definitive plan reflects that fact. [Note 6] There is no dispute that the drainage from the subdivision will primarily reach Massapoag Brook. The issue is whether the definitive plan reflects that.

The use of contour lines to show the direction in which water will flow is an accepted method of showing the direction water will flow. The definitive plan therefore does show the course of discharge, at least within the subdivision. It is a reasonable assumption, however, that somewhere in the 140' space between the last contour line and Massapoag Brook, that some intervening geological formation could exist which would impede drainage. In order to protect third persons with an interest, who might examine the plan, it is not an undue burden to require the developer to show the contour lines past the subdivision boundary to Massapoag Brook. Because the contour lines are not depicted beyond the boundary of the subdivision, the course of discharge to Massapoag Brook is not shown by the definitive plan. I therefore rule that the Board was justified in disapproving the definitive plan on that basis.

In summary, the board exceeded its authority in disapproving the definitive plan based on a lack of drainage easements and on the basis of the width of Road A at certain exempt portions of that way. The Board, however, acted properly in disapproving the definitive plan on the bases that certain Town parcels extend significantly into Road A, that slope easements or retaining wall designs were not provided to the Board, and that the definitive plan did not show the course of discharge to the nearest water course. I therefore rule that because the Board had at least one proper basis for disapproval of the definitive plan, that the Board acted properly in its disapproval. I therefore affirm the decision of the Board. The trial of this action was bifurcated so that the issue of the Board's denial of a waiver of road width requirements was reserved; all other issues were tried. The rulings made render the waiver issue moot, [Note 7] and therefore, the action is ready for final judgment on all issues, including the waiver issue.

Judgment accordingly.

EDWARD LYONS, Trustee of Vista Realty Trust, d/b/a Vista Realty vs. THOMAS C. HOUSTON, MARILYN Z. KAHN, MARTIN A. LEVITT, EVELYN W. SUCHECKI, and GEORGE B. BAILEY as they are members of the Planning Board of the Town of Sharon.

EDWARD LYONS, Trustee of Vista Realty Trust, d/b/a Vista Realty vs. THOMAS C. HOUSTON, MARILYN Z. KAHN, MARTIN A. LEVITT, EVELYN W. SUCHECKI, and GEORGE B. BAILEY as they are members of the Planning Board of the Town of Sharon.