The owners of all but two parcels within a twenty-one parcel site containing approximately 289,483 square feet of land situated in the Newtonville section of the City of Newton, in the County of Middlesex, bring this complaint pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 240, §14A and c. 185, §1 (j 1/2) to secure a determination by this Court of the validity of the action of the Board of Aldermen of the City of Newton in rezoning the locus from a manufacturing district to that called a private residence district in the zoning ordinance. The plaintiffs contend that the zoning is arbitrary and unreasonable in light of the neighborhood in which the premises are located, the history of the zoning as applied to the locus and the uses to which the parcels comprising locus, as hereinafter defined, presently are put, whereas the City claims that in the light of the wide discretion given to its legislative body the rezoning must be upheld.

A trial was held at the Land Court on June 20 and 30, 1988 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. Philip Berquist, a real estate appraiser, Barry C. Canner, former Director of Planning and Development for the City of Newton, Arnold Belli, one of the owners of locus, Ralph Schiavone, another such owner, Ronald A. Marini, a landscape contractor and former member of the Board of Aldermen, and Eugene Kennedy, a Newton City Planner, testified and fifteen exhibits, some of which contain multiple parts and including a videotape of traffic conditions in the neighborhood, were introduced into evidence. A view of the locus was taken on August 4, 1988.

Prior to the trial the parties entered into a stipulation for purposes of this action as to the following facts, and on all the evidence I so find and rule.

1. Plaintiff Raymond DeRubeis is an individual who is the record owner of the following four parcels of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, those parcels are Section 23, block 15, lots 22, 24, 26 and Section 23, block 16, lot 4.

2. Plaintiff Clay Chevrolet, Inc. is a Delaware corporation with its principal place of business at 431 Washington Street, Newton, Massachusetts. Clay Chevrolet, Inc. is the record owner of three parcels of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, those parcels are Section 23, block 16, lots 7, 8 and 9.

3. Plaintiff Ralph G. Schiavone is an individual who is the record owner of two parcels of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, those parcels are Section 23, block 16, lots 1 and 2.

4. Plaintiffs Ralph G. Schiavone and Loretta M. Schiavone are individuals who are the record owners of a parcel of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, that parcel is Section 23, block 16, lot 3.

5. Plaintiff Patrick A. Annese is an individual who is the record owner of a parcel of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, that parcel is Section 23, block 16, lot 6.

6. Plaintiff Arnold R. Belli is an individual who is the record owner of two parcels of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, those parcels are Section 23, block 15, lots 20 and 21.

7. Plaintiffs James and Paul Reid are the trustees of Blackmountain Realty Trust, and as such are the record owners of a parcel of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, that parcel is Section 23, block 16, lot 11.

8. Plaintiff Michael F. Iodice, Jr. is the record owner of a parcel of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, that parcel is Section 23, block 16, lot 10.

9. Plaintiffs Antonio and Concetta Venditti are individuals who are the record owners of a parcel of land in the City of Newton, County of Middlesex, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. As described in the City of Newton Engineering Department's assessors' sheets, that parcel is Section 23, block 16, lot 5.

10. The parcels described above and owned by the plaintiffs constitute more than 90% of the land ("the lots") in the manufacturing district at issue in this action. Such parcels together with part of lot 1, Section 23, block 17, containing approximately 9,500 square feet, and part of 20 and 25, Section 23, block 16 are hereinafter collectively described as "the Locus".

11. The defendant, The City of Newton, is a municipal corporation organized and existing under the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts with its principal place of business at City Hall, Newton, County of Middlesex, Massachusetts.

12. The City of Newton adopted its first zoning ordinance on December 27, 1922. At that time, the Locus was zoned Manufacturing. The Locus remained zoned Manufacturing until November 4, 1985. On that date, by Ordinance No. S-135, the Locus was down zoned from Manufacturing. to the Private Residence District

13. The City of Newton Public Works Facility abuts the Locus to the northwest. That Facility was in a Manufacturing zone in 1940. It remained in a Manufacturing zone until July 21, 1951 at which time the City of Newton Public Works Facility Lot was changed from Manufacturing to a parcel without zoning restrictions. It has remained without zoning restrictions since.

14. The area abutting the Locus to the south and west and abutting the City of Newton Public Works Facility to the west shown as a Private Residence District on a plan entitled "City of Newton, Massachusetts Revised: 1974, 1978, 1980, 1983" marked Exhibit 26 was zoned General Residence from the time of the adoption of zoning in Newton in 1922 until November 25, 1940 at which time it was changed to Private Residence. It has remained a private residence district since.

15. By 1951, the area directly south of the Manufacturing District, including the Locus, fronting Washington Street had been changed from Residence D and Business A zones to a Business B zone. It has remained a Business B zone since.

16. Directly contiguous to the Locus, on the east side of Crafts Street, exists a Manufacturing District. That district was created by the adoption of the first zoning ordinance by the City of Newton on December 27, 1922. That district is left unchanged by Ordinance No. S-135, adopted on November 4, 1985, changing the Locus from Manufacturing to a Private Residence District.

17. On August 1, 1985, Newton Ward Alderman Ronald A. Marini filed with the City Clerk's Office a Ten Citizen Taxpayer's Petition, Petition No. 559-85, to rezone the Locus from a Manufacturing District to a Private Residence District.

18. Petition No. 559-85 was noticed for public hearing on September 9, 1985 by a subcommittee of the Board of Aldermen known as the "Land Use Committee".

19. On September 9 , 1985, the plaintiffs submitted a Statement of Objections to Petition No. 559-85 to the Land Use Committee.

20. A public hearing on Petition No. 559-85 was held jointly by the Land Use Committee of the Board of Aldermen and the Department of Planning and Development on September 9, 1985. After public comments were solicited from interested parties, the Land Use Committee and the Department of Planning and Development announced that they would hold a working session on the matter on October 28, 1985.

21. On October 28, 1985, the Land Use Committee voted to recommend that the Board of Aldermen adopt Petition No. 559-85.

22. On November 4, 1985, the Board of Aldermen voted to adopt Petition No. 559-85 and rezone the Locus from a Manufacturing District to a Private Residence District. No other area was affected by this change of zone.

I further find and rule as follows:

23. The ordinance to which plaintiffs object was adopted on November 4, 1985 as Ordinance No. S-135 and reads as follows:

BE IT ORDAINED BY THE BOARD OF ALDERMEN OF THE CITY OF NEWTON, AS FOLLOWS:

Section 30 of the Revised Ordinances of Newton, Mass., 1985, as amended, be and is hereby further amended by amending sheets of plans entitled "City of Newton, Mass., Zoning Plans" dated June 21, 1951, as amended to date, by changing certain district boundaries from present zoning district to the Private Residence District (Crafts Street/Maguire Court).

Changing the following described real estate now in Manufacturing District to Private Residence District:

Land located on Crafts Street and Maguire Court, Ward 2, Section 23, Block 15, Lots 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26 containing approximately 117,914 square feet; Section 23, Block 17, part of Lot l, containing approximately 9,500 square feet, Section 23, Block 16, Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, part of 20 and 25, containing approximately 162,069 sqare feet; for an estimated total land area of 289,483 feet.

24. None of the ten taxpayers on whose behalf the petition for change of district was filed lived within or owned property within the locus nor did the Alderman who prepared and filed the petition represent the district which was rezoned.

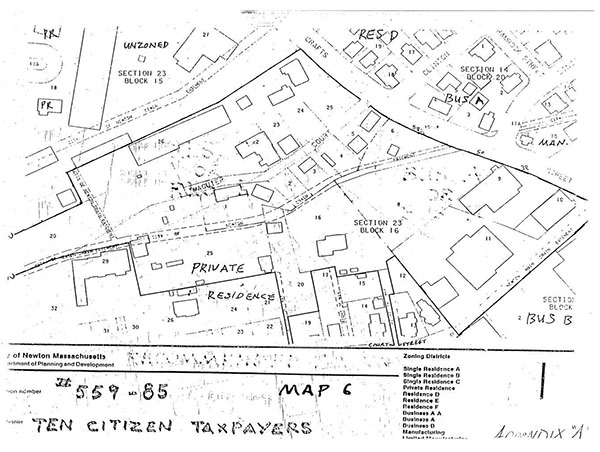

25. Crafts Street is a heavily traveled highway which runs from Washington Street to Watertown. Washington Street in turn parallels the Massachusetts Turnpike and is itself a source of much traffic. Accordingly, a traffic light has been installed at the corner of the two streets. Heavy trucks and equipment use Crafts Street in proceeding to and from the City Yards (and portions of the locus) and Washington Street. Beyond the City Yards., which adjoin the locus on the north, the neighborhood becomes increasingly residential, but from the Purity Supreme Supermarket on Washington Street at the corner of Crafts Street which abuts locus and is zoned for Business in a northerly direction through the site of the City Yards the property within and without the locus is used for non-residential purposes. Adjacent to the supermarket on Washington Street is a large liquor store-at the corner of Court Street. The latter street is the site of many homes which do abut the locus as do homes on Turner Terrace and Wilton Road. Zoning on the northerly side of Washington Street continues in a westerly direction to be Business zoned with the zone extending as far northerly as Court Street at the corner of Central Avenue. Across Crafts Street from the locus the pre-existing Manufacturing District was not rezoned with locus although the erection there by plaintiff Iodice of an office building (the so-called Chatham Office Building or the Iodice Building) may have been the impetus for the present rezoning. A sketch plan from the Planning Department's report shows the location of the various zoning districts, and a copy thereof is attached hereto as Appendix "A".

26. When the locus originally was zoned as a manufacturing district, there were several residences within its boundaries. A few of these remain but are either in a seriously dilapidated condition in which it is doubtful that anyone lawfully lives today, or are used for other non-residential purposes. The principal uses within the area are a gas station and repair garage, the Curtis-Newton lumber yard, the storage of automobiles by Clay Chevrolet, an autobody shop, the Schiavone junkyard and salvage operation, with compacted vehicles and automobile parts storage, a large automobile related warehouse building, the Belli contracting operation with dump trucks, heavy equipment tractors and piles of stored fill and paving materials and two new warehouses at the latter for the storage of salt and sand. Adjacent to the Belli operation is the City's own yards with the public works garage and storage buildings; the site of storage of many City trucks and heavy equipment. The City also has refurbished the former city stables which are relocated in the same area and now include a fire station.

27. At the time of the proposed amendment of the zoning district Barry C. Canner, Director of Planning and Development, reviewed the history of the zoning of the locus, its ownership, the characteristics of the site and the neighborhood and recommended a certain course of action for the Board of Aldermen. The Planning Department proposed that the area from Crafts Street on both sides of Maguire Court westerly to Tyler Terrace and northerly to the Crafts Street end of the locus be rezoned as either Residence D or Residence E or some combination of both, and that the remainder of the Crafts Street frontage from the Purity Supreme northerly to the Maguire Court properties be rezoned as either Business A or Business B. This recommendation was not adopted by the Board of Aldermen which instead adopted the change suggested by the petition of the ten taxpayers. The Connery Associates conducted a Newtonville study as part of the Newton Village study and made an initial report in January of 1986 and in February of 1988 prepared a report of recommendations: Newtonville was Phase IV of the Newton Village study (Exhibits Nos. 13A and 13C). The latter report suggested that the Barnes and Jones Industrial building and the Curtis-Newton Lumber Company should be rezoned to CB-1 to match the proposed zoning of the Purity Supreme site and that the remainder of the area remain in what was Private Residence, now called Moderate Density Residential (MR-1) in view of its proximity to residences. The report suggested, however, that any request for a special permit for town house development which had a density of one unit per 5,000 square feet of lot area should be granted, a goal that may be difficult legally to achieve if based on requirements of a special permit.

28. The report from Mr. Canner to the Mayor (Exhibit No. 3) makes it clear that the potential for new and expanded uses which are permissible under the then existing zoning as a manufacturing district, was the predominant factor in the recommendations of the Planning Department for the zoning change. It was the Department's opinion that such uses were incompatible with the neighborhood. The same reason although not crystalized in the petition, was the root cause of the request for the rezoning.

The guidelines for determining the validity of a municipal zoning enactment have long been established. In Caires v. Building Commissioner of Hingham, 323 Mass. 589 (1949) at page 593 the Court cogently expressed the issues which must be weighed in a case such as this where Justice Ronan wrote:

The ultimate and sole question presented for decision in this case was the power of the inhabitants to enact the amendment. . . . Th e power to make a division of the town into various districts and to designate the purposes for which land in those districts may be used and occupied and to exclude any other purposes rests for its justification on the police power, and that power is to be asserted only if the public health, the public safety and the public welfare, as those terms are fairly broadly construed, will be thereby promoted and protected. A zoning by-law will be sustained unless it is shown that there is no substantial relation between it and the furtherance of any of the general objectives just mentioned. Nectow v. Cambridge, 277 U.S. 183, 188. Pittsfield v. Oleksak, 313 Mass. 553 , 555. Burlington v. Dunn, 318 Mass. 216 , 221. Building Commissioner of Medford v. C. & H. Co., 319 Mass. 273 , 279.

In addition, the Supreme Judicial Court cautioned cities and towns that their zoning regulations must come within the Enabling Act, G.L. c. 40A, since amended by St. 1975, chapter 808 and it held that any local regulation which transcends authority granted by the legislature is invalid. The Court further ruled that "[e]very presumption is to be made in favor of the by-law, and its enforcement will not be refused unless it is shown beyond reasonable doubt that it conflicts with the Constitution or the enabling statute." Numerous cases since Caires have reiterated the same general principles. One of those to which reference frequently has been had is Crall v. Leominster, 362 Mass. 92 (1975) where Justice Quirico expressed exasperation with the continuing number of cases attacking rezoning. In Crall, Justice Quirico turned back to decisions written by Chief Justice Rugg in 1924 in Brett v. Building Commr. of Brookline, 250 Mass. 73 (1924) where it was said "The question to be decided is not whether we approve such a by-law. It is whether we can pronounce it an unreasonable exercise of power having no rational relation to the public safety, public health or public morals." The 1972 opinion then reiterated "that if the reasonableness of a zoning by-law or ordinance is fairly debatable the judgment of the local legislative body responsible for the enactment must be sustained."

Despite the deference paid by the judiciary to the legislative arm of cities and towns, there are instances Where the Court has viewed the rezoning as being invalid. One of the leading cases to reach this result is Schertzer v. Somerville, 345 Mass. 747 , 751 (1963). In Schertzer the Court held that it was arbitrary and unreasonable to zone as residential a parcel of land which had been zoned for business since the original adoption of the city's zoning ordinance, was adjacent to business land, was located in an area changing from residential to business or commercial use and was considered to be properly zoned for business by experts working on a revision of the city's ordinance. One of the factors which influenced the Court was its conclusion that the Schertzer locus was set off from similar adjacent business lots at the "instigation of citizens who objected to a particular proposed public use." Schertzer is helpful too in determining the power of a municipality to change its existing zoning ordinance. Justice Reardon pointed out that a zoning ordinance may be amended to accomplish any of the purposes for which the ordinance was originally enacted. Such action will be sustained unless it is "arbitrary or unreasonable or substantially unrelated to the public health, safety, convenience, morals or welfare." A municipality may, from time to time, he continued, "re-examine the location of a boundary between districts and shift its location as sound zoning dictates. . . . The existing location of the boundaries is a circumstance to be weighed". Helpful too as to the placement or boundary lines is Shapiro v. Cambridge, 340 Mass. 652 (1960) where the Supreme Judicial Court ruled that there are limitations when the boundary lines between districts are changed that are not present when zoning is first adopted and it was held that the Cambridge locus was not sufficiently different from other similarly zoned properties to justify the change. The Court referred to a transcript of a Planning Board hearing which revealed that a desire to prevent an unpopular use was motivation for the zoning amendment. Canteen Corp. v. Pittsfield, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 289 (1976) is another example of a situation where a zoning enactment has been set aside as being without the constraints of G.L. c. 40A in its then form and arbitrary and unreasonable.

The adoption of Ordinance S-135 is an example of municipal action proscribed by the Supreme Judicial Court in Schertzer and Shapiro. The Board of Aldermen ignored the report of the city's Planning Department and failed to await the completion of the Newtonville study which was underway. Rather it proceeded on the request of the taxpayers to rezone the locus for purposes entirely divergent from those for which the properties within the district presently are being used and all of which would become protected nonconforming uses. Moreover, the locus then adjoined properties zoned for business in the south and for manufacturing on the east across Crafts Street and abutted the City Yards to the north. It is true that to the west and southwest locus adjoins a residentially zoned district, but it is hard to imagine the extension of such uses to locus in view of the present uses to which locus is put. Future residential use seems a remote possibility. At least if the recommendations of the Planning Department had been adopted, a more realistic density and use criterion would have been applicable.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that the locus was down zoned to allay the fears of residents without the zone but in the vicinity that an office building might be erected on the locus. This is a factor which the Supreme Judicial Court has at least twice criticized as a rational basis for an enactment. When this factor is weighed together with the proximity of the Washington Street business zone which adjoins locus, the closeness of the Massachusetts Turnpike, the heavy traffic on Crafts Street, the continuation of the manufacturing district across from locus and the adjacent City Yards, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the rezoning was arbitrary and unreasonable and not in furtherance of the objectives served by G.L. c. 40A. I so find and rule for all these reasons that indeed it was arbitrary and unreasonable and not in furtherance of such objectives. I further find and rule that ordinance S-135 falls within the proscriptions illustrated by the Schertzer and Shapiro decisions and is an invalid enactment.

The plaintiffs argue that the action of the Board of Aldermen amounted to a taking, albeit a temporary one on the result which I have reached, for which they are entitled to compensation in accordance with recent pronouncements of the Supreme Court of the United States. See Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 107 S. Ct . 3141 (1987). However, the action of the Board of Aldermen in this particular situation does not amount to a taking either by the state's standards set forth in Lovequist v. Conservation Commission of Dennis, 379 Mass. 7 (1979) or those of the United States in Agins v. City of Tiburon, 447 U.S. 255 (1980). There was no evidence that the plaintiffs sought to develop their land for purposes permitted by the original zone but proscribed by the amendment, for which they might have been entitled to compensation. Moreover, the existing uses were protected as non-conforming, and there were other uses authorized

under the rezoning which might have been available to the plaintiffs had they wished to utilize such provisions.

Judgment accordingly.

RAYMOND DeRUBEIS, ANNA DeRUBEIS, CLAY CHEVROLET, INC., RALPH G. SCHIAVONE, LORETTA M. SCHIAVONE, PATRICK A. ANNESE, ARNOLD R. BELLI, JAMES REID, PAUL REID, MICHAEL F. IODICE, JR., ANTONIO VENDITTI and CONCETTA VENDITTI vs. THE CITY OF NEWTON.

RAYMOND DeRUBEIS, ANNA DeRUBEIS, CLAY CHEVROLET, INC., RALPH G. SCHIAVONE, LORETTA M. SCHIAVONE, PATRICK A. ANNESE, ARNOLD R. BELLI, JAMES REID, PAUL REID, MICHAEL F. IODICE, JR., ANTONIO VENDITTI and CONCETTA VENDITTI vs. THE CITY OF NEWTON.