FRANCIS A. MOLLA, et al, vs. THE TOWN OF FRANKLIN, et al.

FRANCIS A. MOLLA, et al, vs. THE TOWN OF FRANKLIN, et al.

MISC 129682

June 30, 1989

Norfolk, ss.

SULLIVAN, C. J.

FRANCIS A. MOLLA, et al, vs. THE TOWN OF FRANKLIN, et al.

FRANCIS A. MOLLA, et al, vs. THE TOWN OF FRANKLIN, et al.

SULLIVAN, C. J.

Interstate 495 runs through the Town of Franklin in the County of Norfolk, and like many other Massachusetts municipalities to which there is now easy access from the construction of interstate network of highways, Franklin has been experiencing untoward growth. This action was precipitated by the adoption by the Town Council of six by-laws and one resolution affecting the water and sewer infrastructure of the Town. The plaintiffs are the owners and developers of various proposed residential developments in the Town of Franklin who alleged that their proposals have been adversely impacted by the legislative enactments which they here attack. The action was originally filed on September 20, 1988 pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 240, s. 14A and c. 185, s. 1 (j 1/2) and c. 231A, s. 1, et seq.

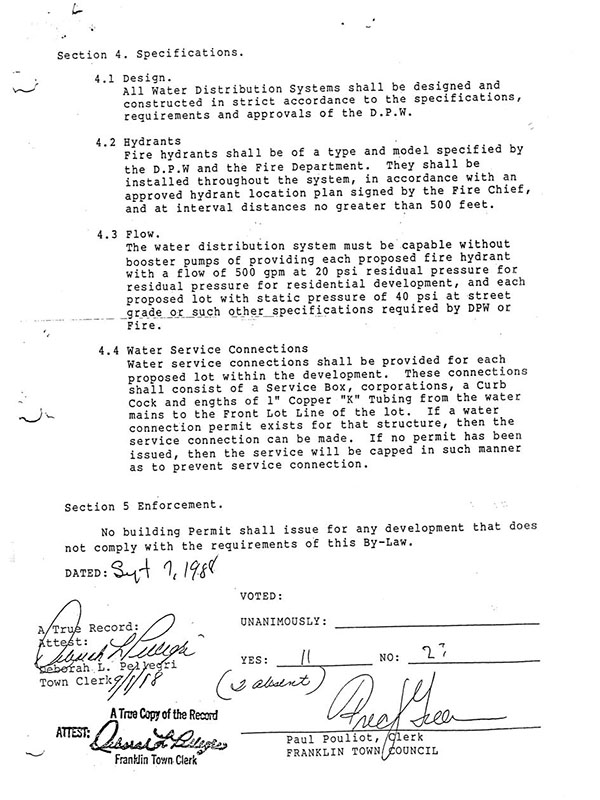

The enactments of which the plaintiffs complain are Town By-Law Amendment 86-72 (Rate of Growth Amendment); Town By-Law Amendment 86-81 (Water Connection Amendment); Town By-Law Amendment 87-96 (Sewer Connection Amendment); Resolution 88-46 (Water Moratorium); Town By-Law Amendment 87-98 (Sewer Lift Station Fee); Town By-Law 88-137 (Water Main Amendment). [Note 1]

The plaintiffs by this action seek a declaration that certain provisions of the Moratorium are invalid; [Note 2] that the Rate of Growth Amendment and Water Connection Amendment have expired by their own terms; that the Sewer Connection Amendment and Lift Station Amendment are invalid; that together the Town's actions preserved to the by-laws constitute an inverse taking by eminent domain for which they should be compensated; and that the Town of Franklin is obliged to supply water to projects which abut Town ways containing Town water mains.

The defendants, however, argue that the enactments were valid exercises of municipal power pursuant to the Home Rule Amendment; that there has been no taking for which the plaintiffs are entitled to compensation; and that the Town has no obligation to supply water to a subdivision even though the developer has constructed water mains therein and the subdivision abuts a Town way in which its water mains are situated. A more precise description of the arguments of both the plaintiffs and the defendants as to each of the by-laws will be set forth later in this decision.

A trial was held at the Land Court on the following six days: January 30, January 31, February 1, 2 and 3, and February 16, 1989. A stenographer was appointed to record and later transcribe the testimony for each day of trial. Patrick Marguerite; Francis Molla; Paul Shew, Franklin Town Administrator; Denis Marguerite; Roger Rondeau; Douglas Rondeau; Carl Smith; and Patrick Hughes all testified. Thirty-six exhibits were introduced into evidence, certain of these containing multiple parts. Two chalks were presented for the assistance of the Court and three items were marked for identification. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. Of the witnesses, Paul Shew, the Town Administrator, was called both by the plaintiffs and defendants and Patrick Hughes, a civil engineer employed by Camp, Dresser and McKee ("CDM"), which currently is retained by the Town of Franklin as a consultant to perform miscellaneous water and sewer services, testified for the Town. The other witnesses either were plaintiffs, employed by the plaintiffs, or witnesses for the plaintiffs.

As set forth above, the Court already has ruled on many of the legal issues involved in the litigation. There are, however, certain motions made in the course of the trial which were either ruled on in open Court or reserved for later decision. In order that the record now be clear, I make the following ruling on these diverse matters.

On January 31, 1989 the defendants made a motion in limine to preclude the plaintiffs from offering evidence regarding reasoning, thought process, opinions or statements of municipal parties, officials or employees. The Court declined to make a blanket ruling in advance of trial, but rather ruled on the admissibility of such matters as the process of interrogation proceeded during the course of the trial. A similar approach was taken on the defendants' motion in limine to preclude the plaintiffs from offering evidence regarding availability of additional or less restrictive alternatives, and no such evidence was brought. The plaintiffs moved to exclude evidence on issues concerning the state of the water supply in the Town of Franklin as well as the Town's efforts to expand or conserve that supply and this motion in effect was granted during the course of the trial and no such evidence appears in the record. Finally, the defendants moved both at the close of the plaintiffs' evidence and at the close of all evidence for a dismissal of the action or for a directed finding pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 41(b) (2) which the Court took under advisement and now denies.

The issues in brief which remain to be decided include a determination as to whether the Growth Rate Amendment and Water Connection Moratorium, if otherwise valid, have now expired by their own terms. There also is the legal question posed by the imposition of a $1,500 sewer connection charge and a $100,000 sewer lift station charge. Finally, there is the question of the validity of the Water Moratorium which the Court heretofore has ruled was invalidly adopted as a resolution. Since there has been no Court decision on the validity of a moratorium enacted by a city or town without express authority from the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering ("DEQE"), the parties have requested that the Court discuss the validity of the moratorium on a broader ground than difference between the by-law and a resolution. The final issues in the case center on the question as to whether the legislation individually, or taken as a whole, is inverse condemnation for which the land owner is entitled to compensation pursuant to the provisions of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution made applicable to the states by the Fourteenth Amendment. The amended complaint raises the question only as to the Massachusetts Constitution which, of course, recognizes the same principal although there is a somewhat different standard of determining due process considerations. Any award of damages should inverse condemnation be found, was postponed and not considered during the trial. The provisions of the various enactments by the Town Council of Franklin are crucial to an understanding of this decision. Accordingly, copies thereof have been attached hereto.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

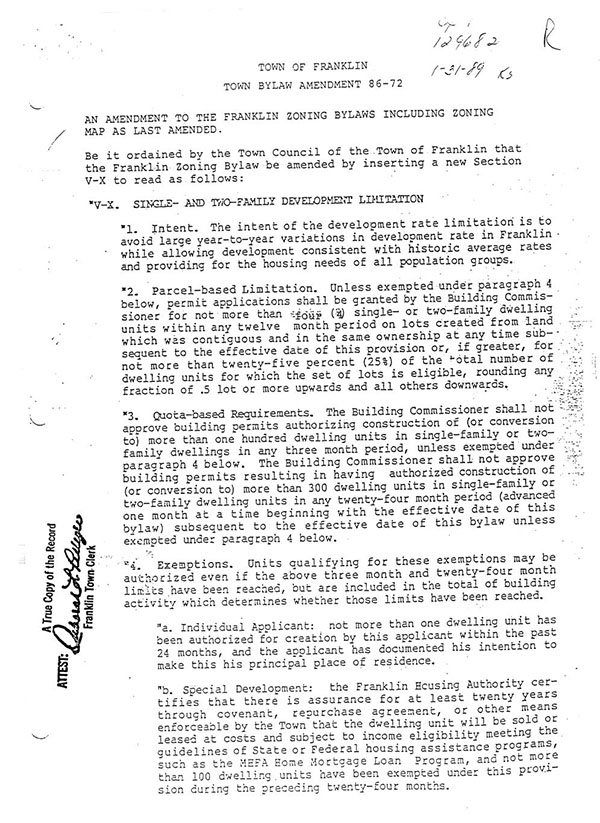

1. On October 8, 1986 the Town Council for the Town of Franklin adopted an amendment to the Franklin Zoning By-Law by inserting a new Section V-X which provided that the development of any parcel be limited to not more than four single or two-family dwelling units within any 12 month period, or if greater, not more than 25% of the dwelling units for the proposed development. There also was an overall limitation of 100 dwelling units in single or two-family dwellings in any three month period or 300 dwellings in any 24 month period, as well as in certain other provisions not here material. The By-Law specifically provided as follows:

"V-X. SINGLE- AND TWO-FAMILY DEVELOPMENT LIMITATION

"1. Intent. The intent of the development rate limitation is to avoid large year-to-year variations in development rate in Franklin while allowing development consistent with historic average rates and providing for the housing needs of all poptilation groups.

"2. Parcel-based Limitation. Unless exempted under paragraph 4 below, permit applications shall be granted by the Building Commissioner for not more than four (4) single- or two-family dwelling units within any twelve month period on lots created from land which was contiguous and in the same ownership at any time subsequent to the effective date of this provision or, if greater, for not more than twenty-five percent (25%) of the total number of dwelling units for which the set of lots is eligible, rounding any fraction of .5 lot or more upwards and all others downwards.

"3. Quota-based Requirements. The Building Commissioner shall not approve building permits authorizing construction of (or conversion to) more than one hundred dwelling units in single-family or two-family dwellings in any three month period, unless exempted under paragraph 4 below. The Building Commissioner shall not approve building permits resulting in having authorized construction of (or conversion to) more than 300 dwelling units in single-family or two-family dwelling units in any twenty-four month period (advanced one month at a time beginning with the effective date of this bylaw) subsequent to the effective date of this bylaw unless exempted under paragraph 4 below.

"4. Exemptions. Units qualifying for these exemptions may be authorized even if the above three month and twenty-four month limits have been reached, but are included in the total of building activity which determines whether those limits have been reached.

"a. Individual Applicant: not more than one dwelling unit has been authorized for creation by this applicant within the past 24 months, and the applicant has documented his intention to make this his principal place of residence.

"b. Special Development: the Franklin Housing Authority certifies that there is assurance for at least twenty years through covenant, repurchase agreement, or other means enforceable by the Town that the dwelling unit will be sold or leased at costs and subject to income eligibility meeting the guidelines of State or Federal housing assistance programs, such as the MHFA Home Mortgage Loan Program, and not more than 100 dwelling units have been exempted under this provision during the preceding twenty-four months.

"c. Statutorily Exempt Development: the lot is protected from application of these limitations because of the provisions of Section 6 of Chapter 40A, G.L.

"Applications refused because of this limitation shall be held in chronological sequence based upon the time of complete application to the Building Commissioner's office, and acted upon in that order as soon as authorizations are possible within the 300-unit limit.

"4. Expiration. Section V-X shall expire December 31, 1990 or, if earlier, on the date that development of a new Well #10 has been given final approval by DEQE and full construction funding has been approved by the Town Council. Upon its expiration, any timing limitations previously placed on building permit availability under Section V-X shall no longer be enforced, but any housing cost or income stipulations upon which permits were earlier qualified shall remain in full force and effect."

The Rate of Growth Amendment referred to in paragraph 1 is the only one of the amendments specifically adopted pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 40A, s. 5, with the safeguards provided in the statute. There is a question as to whether the other legislative enactments are so intertwined that they too should have been adopted as a part of the Zoning By-Law.

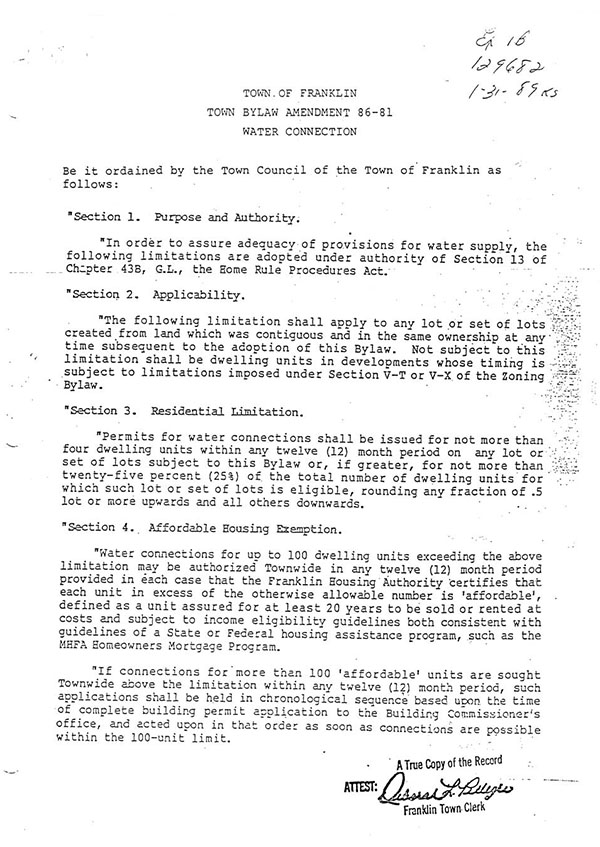

2. Two weeks later the Town Council enacted a water connection provision which imposed a requirement that permits for water connections were to be issued for not more than four dwelling units within any 12 month period on any lot or set of lots created from land which was contiguous and in the same ownership at any time subsequent to the adoption of the By-Law, or if greater, for not more than 25% of the total number of eligible dwelling units. The Water Connection By-Law also had provisions affecting new non-residential developments. The Water Connection By-Law had the same expiration date provisions as the Rate of Growth Amendment.

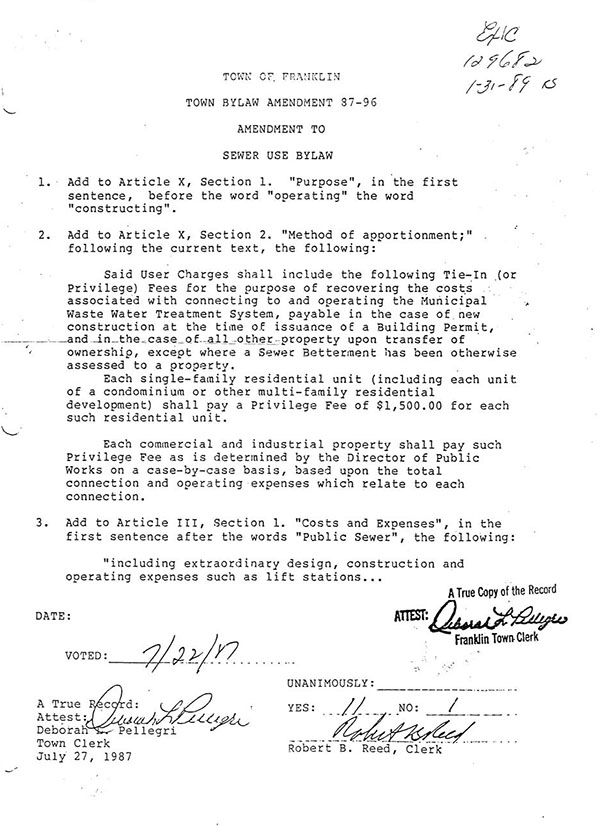

3. The following year on July 22, 1987, the Town Council adopted a Sewer Use By-Law which imposed a Privilege Fee of $1,500 for each single-family residential unit. The language of the By-Law is ambiguous and reads as follows:

Said User Charges shall include the following TieIn (or Privilege) Fees for the purpose of recovering the costs associated with connecting to and operating the Municipal Waste Water Treatment System, payable in the case of new construction at the time of issuance of a Building Permit, and in the case of all other property upon transfer of ownership, except where a Sewer Betterment has been otherwise assessed to a property.

Each single-family residential unit (including each unit of a condominium or other multi-family residential development) shall pay a Privilege Fee of $1,500.00 for each such residential unit.

In addition to the foregoing provisions as to a residential unit, the By-Law left to the Director of Public Works the determination of the Privilege Fee to be imposed on commercial and industrial property with the inclusion of the following paragraph:

Each commercial and industrial property shall pay such Privilege Fee as is determined by the Director of Public Works on a case-by-case basis, based upon the total connection and operating expenses which relate to each connection.

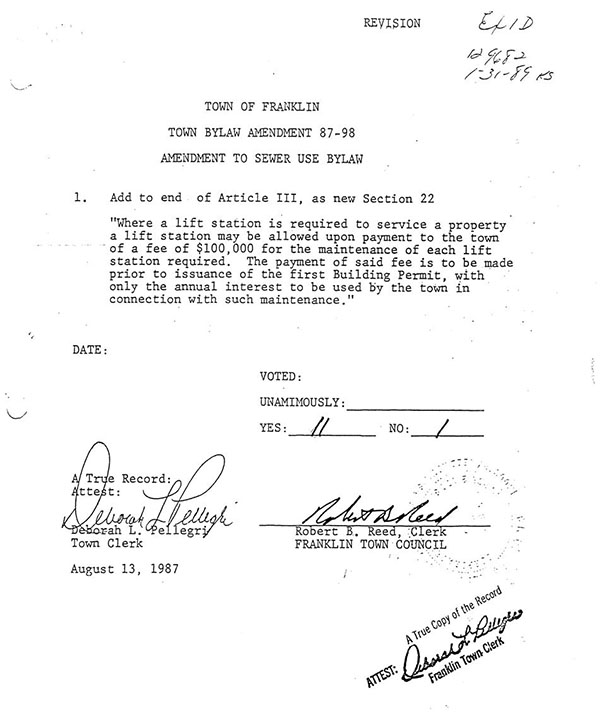

4. Later in the summer of 1987 the Town Council provided for the so-called fee of $100,000 in circumstances where a lift station is required to service a property.

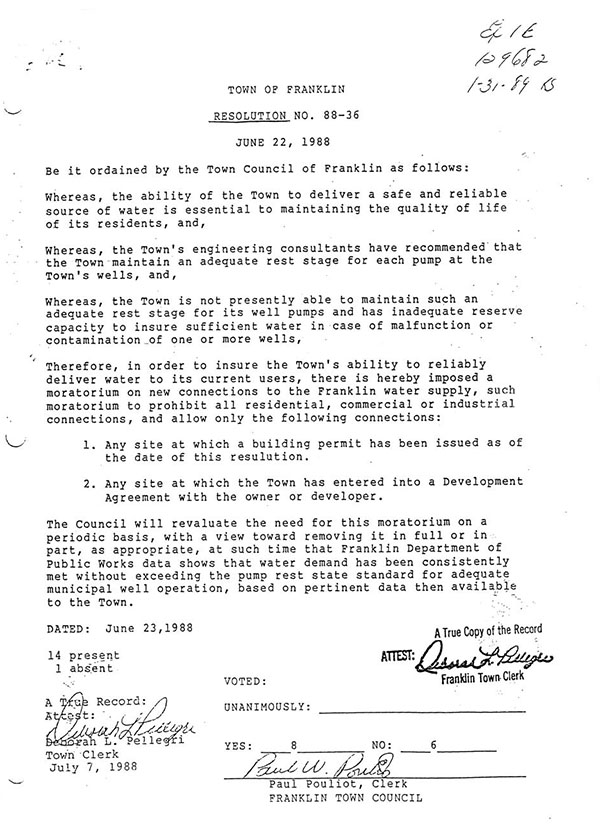

5. The Town Council adopted by resolution on June 23, 1988 a complete moratorium on all water connections whether for residential, commercial or indstrial properties, except in instances where a building permit had been issued or the Town had entered into a development agreement. The moratorium was subsequently amended to define its language. One example of this is the insertion of a provision requiring approval by the Council of a Development Agreement.

6. On April 1, 1986 the voters of Franklin adopted a non-binding referendum in favor of limiting the number of residential building permits issued each year by a vote of 1778 to 336 (Exhibit No. 16). The By-Laws and resolution set forth above were adopted after the referendum.

7. About June 21, 1987, the Franklin Water and Sewer Superintendent requested that DEQE declare a water emergency and authorize the Town to restrict the use of water, and approximately one month later DEQE did issue a Declaration of Water Emergency. The state agency extended the expiration date of the 1987 Declaration in September of that year until November 1, 1987.

8. In 1988 DEQE issued a Declaration of Water Emergency in which it authorized the Franklin Department of Public Works to "restrict use of water in whatever reasonable way it portends to be necessary". This Declaration expired on November 18, 1988.

9. By letter dated January 19, 1989 addressed to the Town Manager, DEQE refused to extend the Declaration of Water Emergency requested by the Town in its letter of December 6, 1988. The Department determined on the findings made in its review that no Declaration of Water emergency was necessary. The letter also served as a notification that the Declaration of Water Emergency presently in effect would terminate upon receipt of the letter (Exhibit No. 5). The Town thereafter requested the Commonwealth to reconsider its position in a letter from Mr. Shew, the Deputy Regional Environmental Engineer (Exhibit No. 5A), but the Commonwealth declined to take any further action by letter dated February 14, 1989 (Exhibit No. 5B).

10. The Town Council voted on October 12, 1988 the funding necessary for the construction of Wells Nos. 9 and 10 by appropriating the sum of $1,900,000 for the development of the wells and the laying and relaying of water mains (Exhibit No. 3) and by letter dated December 21, 1988 DEQE approved the site for the installation of a permanent water supply works subject to five standard conditions for the installation of the well (Exhibit No. 4). The relevant wording of the approval is as follows:

The Department is of the opinion that the information submitted by your consulting engineer relative to the performance of the prolonged pumping test, water quality testing and determination of Zone II is in conformance with the Department's "Guidelines for Public Water Systems". Consequently, the Department hereby approves the subject site for the installation of permanent water supply works with the following provisions:

1. All land within 400 feet of the proposed gravel packed well must be acquired for public water supply purposes. In this regard, it is required that you obtain the approval of the Department before acquiring the land. In order to initiate this process, you or your engineers must submit two (2) copies of a plan of the land to be acquired, indicate the owners of record, and request a public hearing under the provisions of Chapter 40, Section 41 of the General Laws.

2. The pumping rate for the well shall not exceed 300 gallons per minute and shall not be pumped for more than twelve hours per day. The pumping equipment installation shall include drawdown limiting control devices.

3. Water produced from this site will require treatment for ph correction. Be advised that any proposed treatment works must be submitted to this office for review and approval.

4. Plans and specifications for the pumping station, and appurtenant equipment must be approved by the Department prior to the start of any construction.

5. Pursuant to Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 30, Section 62A, and 10.04(g) of the Regulations governing implementation of the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act, an Environmental Notification Form must be filed for this project and acted upon by the Secretary of Environmental Affairs prior to the start of any construction.

Furthermore, the Department recommends that the Board of Water Commissioners utilize the Zone II information to promote the adoption of local measures by the Town of Franklin that would afford precaution within sensitive aquifer boundaries.

11. The Town of Franklin, acting through its Town Administrator, entered into several development agreements (but none with the plaintiffs) pursuant to the provisions of the By-Laws set forth above. In one such agreement dated January 2, 1986, the Town agreed to make available to the developer 250,000 gallons average daily flow service for the so-called Forge Park. This agreement between the Town of Franklin and Forge Park Limited Partnership is Exhibit No. 34A. Exhibit No. 34B is an agreement between the Town and J & J Corrugated Box Corp., dated October 15, 1986, covering the administration of a community development action grant. The Town also agreed with a third developer who applied for a Public Works Economic Development Grant to assist in the development of a shopping center known as Franklin Village (Exhibit No. 34C). In a development agreement dated as of May 22, 1985 (Exhibit No. 34D) between the Town of Franklin and Franklin Industrial Park Trust, the Town agreed to be responsible for $700,000 of certain of the construction and design costs.

12. Plaintiff Patrick Marguerite, a life-long resident of Franklin, owns the so-called Spruce Pond Project which is being developed by Marguerite Building Corp. ("MBC") of which he is a principal. Seventy-five of one hundred residential units have been sold. In connection with the development the corporation replaced the existing six inch water line in Union Street with a twelve inch main as well as replacing a section of the old town sewer line approximately one mile to the northwest of the project, all as required by the terms of its special permit, at a cost of approximately $200,000. It also installed in 1986-87 water mains and sewer lines throughout the project. All of the residential units are connected to the Town sewer and water as are the health club and convenience store. Plans for the project also include a commercial village of offices and small stores designed with a Nantucket style of architecture to be built around a central gazebo. The village has not as yet been built, because water tie-in permits were refused even though there had previously been six existing buildings on the site which had been tied in to the system. The Town refused to treat the special permit as a development agreement so MBC drilled a well on the site, but the flow produced was insufficient. Four potential tenants who had signed commitments in the form of "Intents to Lease" have been lost. The project illustrates the Town's policy of requiring the installation of water and sewer lines in developments even though permission to connect is denied and the land owner left to the drilling of wells.

13. MBC owns the Indian Ledge Project which it is developing and which consists of a 20 lot residential subdivision that extends from Summer Street where Town water is situated. The developer at its expense has installed water mains, sewer lines, drainage lines, and a base coat on the road within the subdivision. The developer had planned to install a gravity sewer line to the existing sewer lift station at Lewis Street, just north of the Indian Ledge Project and to upgrade the sewer lift station. The developer designed the lift station to service the 20 homes at Indian Ledge, but the Franklin Department of Public Works would not approve it since the department wanted a station large enough also to service the sewerage from Lewis Street and an adjacent undeveloped area. The cost of the new lift station was $250,000 as compared to an upgrade of the existing station at $50,000. While negotiations were continuing, the Water Connection Amendment was adopted which limited MBC to a connection for 25% of the lots in the Town's water system. Negotiations for an increase in the number of lots upon developer's agreement to build a new lift station were not fruitful. A lift station is a square concrete or cement block building below which are located a large chamber, two pumps and a secondary power source. In the present case, pilings were required in order to build the station which was completed in the fall of 1988. The Town had required the station be deep enough to be at a lower elevation than Lewis Street so that it could be fed from Lewis Street by means of a gravity sewer. No lift station fee was required for this lift station, and it is being mainained by the Town. At this point, the Water Moratorium was enacted which left the developer with a 20 lot subdivision, an expensive lift station and no water. Four wells have been drilled and four other lots sold to another developer. The fifth well was non-productive. Four sewer connection fees of $1,500 per lot have also been paid.

14. MBC plans to develop a 34 lot residential subdivision in the northeast corner of Franklin with frontage on Populatic Street. Town water abuts the subdivision on its northerly boundary with distribution lines for Town Well # 8 running along the property line. The developer also has an easement across the adjacent property from which it physically could tie into Town water. After the moratorium was adopted, representatives of the corporation attempted to obtain a waiver for the requirement that Town water lines be built in the subdivision. The requirement was imposed by town authorities, however, that water lines must be installed with yellow hydrants if the line was dry, red hydrants if it was wet. Installation of water and sewer lines has been delayed until the litigation is resolved.

15. MBC also has a 25 lot single-family residential subdivision called Woodlocke Acres which it both owns and is developing. The Planning Board has waived the requirement of Town water lines, but building and water connection permits have not been obtained since the moratorium. Efforts to sell the property have not been successful.

16. MBC also owns and is developing a 43 lot single-family subdivision called Cobblestone Woods which has frontage on three town ways, in two of which there are Town water mains. In the fall of 1986 and spring of 1987 MBC installed a water main throughout the development where 14 homes had been built. However, due to the Water Connection Amendment, only ten homes have been tied into Town water, and wells have been built for the other four homes. A sewer connection fee of $1,500 has been paid for all 14 houses.

17. Francis A. Molla is a long-time resident of Franklin as well as an active citizen who has been both a member and chairman of the Franklin School Committee, as well as founder and past president of the Franklin Builders Association. The Association supported the Rate of Growth By-Law and the Water Connection ByLaw, but only on the basis that the expiration date of the By-Laws be tied in to the DEQE approval date and not to the construction date or the date the wells actually came on line. This position was expressed during the Town Council meeting. Mr. Molla acquired the land comprising 1750 Estates in April of 1988 for a five lot residential subdivision on which of one a house was constructed for the seller. Water and sewer lines were installed by the developer. The seller's new house is situated on Lot 5, and Molla constructed a new house in Lot 2, neither of which are connected to Town waters, but have private wells, the cost of the former being $9,000 and the latter $5,000 even though there is Town water five feet from the front lot line. Offers to purchase Lots 3 and 6 were withdrawn after the Town Council refused to lift the moratorium. Fifty dollars has been paid for each lot for a sewer connection fee and $1,500 for the sewer privilege fee.

18. Mr. Molla also is a partner in Pleasant View Associates which owns and is developing Pleasant View Estates, a 23 lot single-family subdivision. There are Town water lines in Pleasant Street, and the developer has installed water and sewer lines in the subdivision and constructed a sewer lift station which the Town required be large enough to service 75 houses although the subdivision has only 23 lots. No lift station fee was required since the station was approved before the enactment of the fee, and the Town has assumed responsibility for the upkeep and maintenance as of February 1, 1989. Sewer connection fees have been paid for Lots 4, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18 and 19. Seven houses have been constructed in the subdivision, and sixteen lots remain unsold. Six houses are connected to Town water and one house built before the moratorium is serviced by its own well. Terms of the purchase and sale agreement covering a seventh house were being negotiated when the moratorium was enacted, and the agreement was thereafter signed at the same price although the developer then had to drill a well at a cost of approximately $5,500 to $6,000. Other lots in the subdivision are being marketed, but no offers have been received.

19. Union Square is owned by Union Square Development, Inc. of which Mr. Molla is a principal. Formerly the property of Clark, Cutler & McDermott Company for approximately 50 years, it is located in the central district of Franklin and has frontage on Union Street. The property consists of the former Ray Woolen Co., a woolen mill built in 1876, a three story brick historic structure now designated as Building B, three other buildings in the lower corner of the property which house business entities, and a parking lot on the eastern portion of the property. In the northernmost portion of the property there is another large wooden storage building which is presently unoccupied. Below and directly in back of the Noone building are the remnants of a two-store brick and wooden mill building that was gutted in a 1919 explosion. The building on the eastern portion of the property housed four tenants when the property was acquired by Mr. Molla.

20. There were three connections to Town water when the property was purchased in March/April of 1988. These connections remain. One connection comes into the property from the Town Water Main in Union Street. It then runs alongside the existing commercial building. A second connection enters the property from Union Street through the parking lot and then services the Mill building. A third connection enters the property from the Town Water Main on Sugar Beet Street and services the sprinkler system in the Mill building. All three connections were being used by the tenants when the property was purchased; the connections are still being used.

21. The property is currently zoned business. When he originally purchased the property, Mr. Molla intended to rehabilitate the Mill building into a series of commercial shops, offices and light manufacturing. At the suggestion of Al Lima, then Town Planner for the Town of Franklin, Mr. Molla assembled a development team to study the possibility of converting the structures into apartments under the then newly enacted "MultiFamily by Conversion" By-Law. The team included architects, engineers and socio-economic planners. A concept plan and presentation booklet were completed. Under the rehabilitation plan the existing mill would remain and be refurbished. A second building would be constructed to the rear of the mill and connected to the mill building by a bridged walkway. The remaining three existing buildings would be removed to accommodate parking. Twenty-five percent of the apartments would be used for low to moderate income housing.

22. The Planning Board unanimously voted to recommend the rezoning to the Town Meeting. The Town Council voted to send the proposal to a first reading in the By-Law process. The plan was unanimously supported by the neighborhood. During the second reading the Management Team recommended to postpone the rezoning since it was in conjunction with this litigation. The Town Council voted to postpone the rezoning to a later date. The Council later voted against the rezoning by a vote of 8-4-1. Mr. Molla stated that it is his understanding that if the property remains light manufacturing, the moratorium will not affect it since the water connections are already being used; the Town officials feel otherwise.

23. Mr. Molla requested a Development Agreement from Mr. Shew and Norman MacNeal, Contracts Administrator for Franklin, in the fall of 1988. He also requested one for Pleasant View and 1750 Estates. By letter dated November 18, 1988 Mr. Shew responded that the Development Agreement would be granted if it benefitted the Town. Mr. Molla did not respond since he saw no point in doing so in light of the money he had already expended on the Plesant View water system.

24. At a time when the Town Council was scheduled to reevaluate the moratorium, the Town Administrator prepared a memorandum dated September 2, 1988 which so far as is material, read as follows:

With the appropriation of funds for Well #10, we will find ourselves near a point which will extinguish the build-out legislation. DEQE approval for that well is expected once the appropriation has been made. That would find us in a situation where there are virtually no controls on limited use of the water system, but for the moratorium.

25. Mr. Shew, in testifying, stated that the purpose of the Lift Station Amendment was to discourage lift stations. The fee of $100,000 was chosen in part, because it was large enough to discourage the construction of lift stations and would provide enough interest to cover the estimated $13,000 average annual maintenance cost of a lift station based on the Town's experience during the preceding five years. Although the By-Law does not so state, the Town does not require a fee for construction of a lift station which will not be turned over to the Town. Mr. Shew recognized that the Rate of Growth Amendment would not apply to the circumstances protected by G.L. c. 40A, s. 6, and accordingly the Town adopted the Water Connection Amendment to eliminate the problem of grandfathering.

26. The Town also allegedly has not applied the Sewer Connection Amendment retroactively so that if a property now is sold where no betterment has been paid, but where any building thereon was constructed before the adoption of the By-Law, there is no assessment of a $1,500 charge. Originally, it had been intended to implement a requirement to be adopted by the Board of Health that there be a connection to the Town sewer upon transfer of ownership of any property. The Board of Health has not enacted this requirement. The sewer connection fee for commercial or industrial property is determined by the Director of Public Works on a case by case basis. There also is an annual sewer usage fee for every property in Franklin which is connected to the sewer. The Town also assesses betterments for sewers which may be paid over a period of years, but if the developer installs the sewer line, then no betterment is assessed.

27. No development agreement has been executed since the moratorium was enacted. No standards were promulgated before the moratorium for the development agreement, and none have been promulgated since although it is clear that in practice a water component is required.

28. CDM prepared a study for the Town to determine the most equitable system of assessment in connection with the Shepard's Brook Project. Laterals were constructed off the Shepard's Brook Interceptor, and betterments were assessed to the property on laterals in the amount of $2,000 per property. The privilege fee was devised by a breakdown comparable to the entire cost of the project. CDM recommended a sewer privilege fee of $1,582 to compensate the benefit of non-abutters to connect to the Shepard's Brook system, but their report did not state that every plant in Town connected to a sewer would pay a charge.

29. Dennis Marguerite is a developer and builder who has lived in Franklin all his life and now is involved in five residential subdivisions, three of which are in the early planning stages. A fourth subdivision called Hampton Court is a 33 lot single-family subdivision in which the developer had installed the infrastructure in the summer to early December of last year. Twelve inch pipes were installed in the subdivision at the request of the Director of Public Works. There was a one year delay between approval of the subdivision and construction while the Town waited for funding for a water main extension, and then the moratorium was enacted. No homes have been constructed as yet. The developer elected to install septic systems rather than to tie into the sewer system, because the topography would require a lift station. TheTown legislation did, however, lead to the decision to drill wells. These alternatives may not avail as relief for four of his lots, 19 to 20 inclusive, since the well and septic system must be 100 feet apart (as well as a required distance from adjacent wetlands) and this may not be feasible.

30. White Oaks is a 22 lot subdivision owned and being developed by White Oaks Development Corp. White Oaks Development Corp. is owned by Mr. Marguerite's two sons. Mr. Marguerite has guaranteed the financial note for the subdivision to the bank and is serving as an advisor to his sons. White Oaks has frontage on Chestnut Street in which there is a Town water main. White Oaks was acquired by the Development Corp. in May/June 1988. The definitive subdivision plan was approved by the Planning Board and included provision for Town water. The water distribution system, drainage system, underground electrical and all head walls have been installed. One coat of hot top paving has also been laid. The water main was installed in Longfellow Drive and Kerrie Circle in the summer of 1988.

31. No building permits have been obtained for the subdivision as of yet as there has been a delay of approximately two months in drilling the wells. However, wells have been drilled for Lots 5, 6 and 7. Prior to the enactment of the moratorium, a developer could obtain a water connection permit by simply going to Town Hall and paying a fee. The permit would usually issue within one week. Once the permit was obtained, either the Town or the developer would then perform the connection. The physical process of connection would include digging a trench and connecting the pipes to the Town water stub. A subdivision would have Town water in a couple of hours. The cost of connection would be approximately $400.

32. Mr. Marguerite testified that White Oaks has been connected to the Town sewer and he anticipates paying a $1,500 fee for each connection. Mr. Marguerite has worked on developments in Wellesley and Framingham in 1982-83 and paid sewer connection fees of $25 per connection. In September, 1988 they received an offer to purchase the subdivision for $80,000 to $90,000 a lot. This offer was rejected.

33. Roger Rondeau and his son Douglas testified relative to three subdivisions, Phyllis Lane Extension, Nicholas Estates and West View, none of which have been adversely affected by the municipal regulations.

34. Toll Bros., Inc., a publicly held developer and builder with operations from Maryland to Boston, owns two developments in Franklin, Franklin Chase and Franklin Farms (also known as Charles River Farms). Franklin Chase is a 58 lot single family subdivision owned by Franklin Chase Ltd. Partnership of which Toll Bros. is a partner and being developed by Toll Bros., Inc. Franklin Chase is located on Partridge Sreet, a public way in the northwestern portion of Franklin; Partridge Street contains a Town water main. Franklin Chase was acquired by the Limited Partnership in March, 1987 after the Planning Board had approved the subdivision plans with provision for Town water.

Most of the major utilities have been installed. The water distribution system, hydrants, sewers and curbs have been installed. The sidewalks and base coat of asphalt have also been installed. The sewers have been connected to the Town sewer system. Work began on the water and sewer systems in September, 1987 and was completed in June, 1988. The water distribution system is connected to the Town water main and so is a wet line. No person from the Town of Franklin stated that Toll Bros could not build a water distribution system.

Toll Bros. built three model homes and started marketing the subdivision in June, 1988. They have constructed, or are in the process of constructing, fifteen houses; seven of which are connected to the Town water supply. The permits were in place before the moratorium was enacted. No water connection permits have been issued for the remaining eight houses under construction. Approximately fifteen wells have been drilled. One well will be used to provide irrigation to the landscaping. Eight wells will be used to provide water to the eight houses which did not receive water connection permits. The remaining six wells will be used to supply water to future construction on presently unsold lots. Each of the fifteen wells that has been drilled has been drilled to a different depth. The well on Lot 16 was drilled to a depth of over 600 feet and sufficient water was not found. In an attempt to find sufficient water on Lot 16, hydrofracture, a process which employs high pressure to fracture the rock and release trapped water, was used. This process took four to five weeks and yet sufficient water was not found. Toll Bros. has already paid for the water distribution system that was installed in Franklin Chase.

Franklin Farms is a 190 lot residential subdivision with frontage on Oak and Maple Streets; both of which contain Town water mains. Franklin Farms was purchased by Franklin Farms Limited Partnership, of which Toll Bros. is a partner, in October, 1987 and is being developed by Toll Bros. The subdivision plan was approved by the Planning Board on March 9, 1987 and included provision for Town water. Toll Bros. acquired the subdivision after the Planning Board approved it.

Toll Bros. has installed a water distribution system, sewer system and drainage system to sixty lots to the southwest near Oak Street. They began work on this infrastructure in January, 1988 and had substantially completed the work at the time of trial. The water distribution system is a wet line for an area of thirty lots. The line to the remaining thirty lots are not yet wet. While the infrastructure was being installed, a representative of the DPW was frequently at the subdivision; sometimes on a daily basis.

Two model homes were completed in January, 1989 and one model home is still under construction. Two other houses are being constructed as speculation property in that they are being built but have not yet been sold. The two model homes that are completed are serviced by Town water. The building permits for these two homes were issued before the moratorium was enacted. The other three houses will be serviced by private wells. Plans for extension of the water distribution system will depend on the outcome of the Water Main Amendment and Moratorium.

A lift station, the plans for which have been approved, is scheduled for the southeastern portion of the northeastern section of the subdivision near Maple Street. A lift station would be needed since a portion of the subdivision is at a lower elevation than the gravity sewer in Maple Street. The lift station will pump the sewerage up to first section of the subdivision and then it will be serviced by the gravity sewer. The developer has sought a Development Agreement, but it ceased its efforts upon learning that it would have to produce a new water source.

A. Necessity of Enactment as Zoning By-Laws

I turn now to the question of the validity of the several by-laws enacted by the Town. The plaintiffs argue that the measures are so inter-related that they should be weighed as a package. Since the Rate of Growth Amendment clearly was a zoning measure and was adopted as such, the argument continues, the remaining legislation should be deemed zoning enactments also and required to meet the same standards of enactment, particularly since it is apparent that some at least of the provisions were designed to avoid the protection afforded by the General Court to subdivision plans approved by the Planning Board. See G.L. c. 40A, s. 6. [Note 3] The defendants counter that the option lies with the legislative body to select the appropriate form of regulation, and that if it is a proper exercise of the town's police powers to regulate sewer and water connections, it is immaterial that the same result might have been reached through the zoning by-law. I have discussed this area at length in a Superior Court action in which I sat by special designation, City of Chelsea, et al v. Eastern Minerals, Inc., Suffolk Superior Court C.A. No. 85118. The leading case in this field is Rayco Investment Corp. v. Board of Selectmen of Raynham, 368 Mass. 385 (1975), where an attempt by the Town of Raynham to regulate a trailer park which historically had been regulated by the local zoning by-law was held to be invalid. Rayco, however, is a different situation as was (and is) Chelsea. There is no historical pattern to be followed here, but rather an attempt by a town to conserve its resources. The theory of multiple enactments in a non-zoning context survives therefore even though each enactment individually may be vulnerable. I therefore now reach this portion of the decision.

B. Validity of By-Laws

1. Rate of Growth Amendment (86-72)

The sole zoning enactment was limited in duration and by its terms was to expire no later than December 31, 1990. I have found and ruled that it now has expired upon the passage by the Town Council of the necessary funding for the new Well and the approval thereof by DEQE. The Town argues both as to this By-Law and the Water Connection Amendment (86-81) that final approval by DEQE as used in the by-laws means the new well has been built, is on line and has met the requirements of the state agency. This was not the understanding at the time the legislation was adopted nor is it the plain import of the language. I find and rule that the appropriation by the Town of the moneys for the construction of two wells work and the completion of the tests which led to the DEQE letter of December 21, 1988 were the two happenings on which these two by-laws by their own terms terminate. In fact, the DEQE letter advances the outside limit by about one year (from December 31, 1990) and the actual anticipated completion date of April, 1990 by a few months.

With the two year limitation in effect, the validity of the enactment of the Rate of Growth Amendment seems inexorably presaged by the decision of the Supreme Judicial Court in Sturges v. Chilmark, 380 Mass. 246 (1980). Because of the specified duration of the limitation on the issuance of building permits and the apparent necessity (compare, however the Forge Park Agreement) of limiting the demands on Franklin infrastructure, I find and rule that the Rate of Growth By-Law was valid when adopted, and I further find and rule that it has now expired by its own terms.

2. Water Connection Amendment (86-81)

This By-Law essentially sets forth the same provisions as the rate of growth amendment, but was designed to eliminate the grandfathering protection afforded by section 6 of chapter 40A of the General Laws. It differs from the zoning by-law in that it is tied to permits for water connections rather than building permits, but it must fall as inconsistent with the overriding state statute. It is one thing to hold, as I have, that the entire bundle of Franklin regulations need not be enacted with G.L. c. 40A, s. 5 formalities. It is quite another to authorize cities and towns to defeat legislative policy by enacting essentially the same provisions as a facet of its police power to evade statutorily mandated protections. As both Mullen v. Planning Board of Brewster, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 139 (1983); Del Duca v. Town Administrator of Methuen, 368 Mass. 1 (1975) illustrate, local legislation in conflict with state policy must fall. Accordingly, I find and rule that the water connection amendment is inconsistent with G.L. c. 40A, s. 6 and thus unenforceable. I further find and rule that in any event it has expired by its own terms.

3. Sewer Use By-Law (87-96) and Amendment (87-98)

In Franklin there is a $50 sewer connection fee, there is the user fee for the privilege of emptying waste therein, in some circumstances there may be the assessment of the usual sewer betterment assessment with which home owners and real estate attorneys are familiar (see G.L. c. 83, s. 14 and s. 15) and there is the unusual sewer connection fee. There is indeed a provision in General Laws c. 83, s. 17 which provides an alternate method of charging for the benefit of a sewer. Section 17 reads as follows:

s. 17. Payment for Permanent Privilege.

The aldermen of any city except Boston or a town in which main drains or common sewers are laid may determine that a person who uses such main drains or common sewers in any manner, instead of paying an assessment under section fourteen, shall pay for the permanent privilege of his estate such reasonable amount as the aldermen or the sewer commissioners, selectmen or road commissioners shall determine.

There has been only one decision of the Supreme Judicial Court interpreting the statute. In Exeter Realty Corp. v. Bedford, 356 Mass. 399 (1969) the Court upheld the charge to a developer who had constructed the sewer for a privilege fee for the permanent use of the sewer at a rate per front foot, computed at a rate one-half as much as when the Town built the sewer. The Court characterized the charge as a benefit assessment, not a section 16 annual charge. Such an approach remains unusual with only that adopted by Northborough (Exhibit No. 33) called to the Court's attention.

It is clear that section 17 remains a viable approach for a community. It is unclear, however, that the Town can charge the developer who already has constructed the sewer at the same rate as third parties. There are other problems which affect the validity of this legislation. As written, it contains no exclusion for the imposition of a sewer connection fee where the dwelling units were constructed prior to the enactment of the by-law but not sold until after 1987.

There is a further question as to whether the fee is in effect a tax, for the amount was computed on the basis of the cost of the Shepard's Brook interceptor to those served thereby, but was made applicable to all in Franklin.

A final problem with the by-law is the unfettered discretion vested in the Director of Public Works to determine the amount of the privilege fee for commercial and industrial property "on a case-by-case basis, based upon the total connection and operating expenses which relate to each connection". This is an invalid delegation of power. The criteria, if it can accurately be so described, is vague and without the precision required for section 17 assessments. This permeates the entire framework of the enactment which as presently written is violative of due process.

It would be possible, however, to draft the by-law within the framework of chapter 83 and all other applicable principles in such a way as to be valid. When and if rewritten it does set forth standards by which there subject to its provisions can judge what is required. Cf. Castle Estates, Inc. v. Park and Planning Board of Medfield, 344 Mass. 329 , 334 (1962). In its present form, however, I find and rule that it is invalid.

The sewer use by-law was further amended in August 1987 to provide for the payment to the Town of a fee of $100,000 for the maintenance of each lift station required. In Emerson College v. Boston, 391 Mass. 415 (1984) the Supreme Judicial Court in weighing the validity of a Boston ordinance imposing a fire protection charge held that the exaction was an invalid tax, not a permissible fee. To qualify as the latter, the Court enunciated a three-prong test which the challenged legislation was to meet:

1. Is the exaction charged in exchange for a particular governmental service which benefits the party paying the exaction in a manner "not shared by other members of society";

2. Is the exaction paid by choice, in that the party paying the exaction has the option of not utilizing the governmental service and thus avoiding the charge; and

3. Is the exaction collected not to raise revenues, but to compensate the governmental entity providing the services for its expenses.

The sewer lift fee fails the Supreme Judicial Court test on at least two grounds. Some of the plaintiffs were required by the Franklin Department of Public Works to construct larger lift stations than necessary to serve the development so that other areas might benefit. This militates against the charge being construed as a fee under the first prong of the Emerson test. The fee also was placed at a high enough dollar amount to discourage development which needecl a lift station to go forward. This would appear to violate the third prong of the test. Conversely, the income from the capital paid would approximate the amount necessary nonetheless, to pay the annual charges for upkeep although not with mathematical certainty, a factor to be weighed so far as prong three is concerned. On balance, I find and rule that the scales are tipped against the Town so far as the third prong is concerned. The Lift Station Amendment makes no provision for the size of the lift station, a station large enough to service two hundred homes will incur the same fee as a station which services twenty. Since the fee is predicated on the interest it will produce to cover maintenance of the lift station, it would appear that a rational nexus between the fee and the service does not exist. Additionally, the Lift Station Amendment makes no provision that the fee only is to be due if the lift station is turned over to the Town. Thus a developer who builds a lift station but does not turn it over to the Town will theoretically still have to pay the lift station fee. The Town suggests that the proviso "if the station is turned over to the Town" be read into the Amendment. However, the By-Law appears to be unambiguous and so the Court should not attempt "to make repairs in 'faulty' text on the basis of Legislative history and presumed Legislative intent." Rogers v. Metropolitan District Commission, 18 Mass. App. Ct. 337 , review denied 393 Mass. 1102 (1984). For these reasons the Franklin Lift Station Fee does not meet the third prong of the Emerson test.

The final prong, the freedom not to incur the charge, the lift station fee meets the test. Generally the use of a common sewer as opposed to a septic system may be a matter of choice unless there are considerations of health and safety which mandate otherwise. Fluharty v. Board of Selectmen of Harwich, 383 Mass. 14 , 17 (1980).

In summary, then, the net result of the application of the Emerson College principles to the sewer lift station fee is the conclusion that it is an unauthorized tax which must fall.

D. Water Connection Moratorium

The Moratorium was adopted as a resolution on June 23, 1988 (Exhibit No. 1E) and again on July 6, 1988 (Exhibit No. 1F) with certain changes in style and substance not here material. I have already ruled in my decision on the motion for summary judgment that the Town Council fatally erred in adopting the moratorium as a resolution rather than a by-law. [Note 4] Counsel, however, has requested the Court to rule on the validity of the moratorium on other grounds as a guidance to the parties, and I have agreed to do so.

The only decision of the Supreme Judicial Court relative to a moratorium is Collura v. Arlington, 367 Mass. 881 (1975), where the Court found authority in the local town meeting to enact interim zoning for a period of two years affecting apartments only. Neither the Supreme Judicial Court nor the Appeals Court has yet considered a more encompassing moratorium, whether under the provisions of c.40A or under other police powers reserved to local municipalities by the Home Rule Amendment. There is an indirect recognition of the existence of moratoriams in the provisions of the grandfather clause found in c. 40A, s. 6 where protection afforded subdivision plans is extended by periods encompassed by litigation or among other events, moratoriums. G. L. c. 21G, is the Massachusetts Water Mangement Act adopted by the General Court by st. 1985, c. 592. It is clear from the reading of the Act that the management of water emergencies has been deposited in the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering and it is this agency which has the authority to declare a state of water emergency. In section 15 DEQE is given the authority to require the body petitioning for such a declaration to submit a plan designed to bring about an expeditious end to the state of water emergency. This section also sets forth various steps DEQE may require the local authority to take. In section 14 is found DEQE's authority to enforce its orders. In section 16 are found provisions which authorize under certain circumstances a water company, public agency or authority of the Commonwealth or its political subdivisions which is operates a public water system to take by eminent domain land necessary for water supply after the plan designed to end the emergency has been approved. Section 17 gives extensive powers to DEQE to deal with water emergencies. The statutory scheme as it appears in chapter 21 has pre-empted the field and cities and towns have no independent power to declare a moratorium until it has been authorized by DEQE.

It is always difficult to determine whether the legislature intended state powers to supersede those of the local government or whether they are intended to co-exist. In circumstances like the present, however, in applying the standards enunciated by the Supreme Judicial Court in a series of cases including Bloom v. Worcester, 363 Mass. 136 (1973); Wendell v. Attorney General, 394 Mass. 518 (l985); and Warren v. Hazardous Waste Facility Site Safety Council, 392 Mass. 107 (1984), there seems little doubt that there today is no independent power in the municipality to declare a moratorium. In the present instance, DEQE in entering a declaration of emergency never specifically authorized a moratorium on water connections. The earlier declarations envisioned local action of a less drastic nature than a moratorium. As those served by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority are aware, DEQE in view of the drought (and before the heavens proceeded to open) authorized a ban on outside watering during certain hours. It is apparent from Chapter 21G that DEQE has authority to order more stringent regulations. This it did not specifically do, but the wording the agency employed is broad enough to support a proper local enactment of a moratorium. At the time of the last declaration, Franklin impliedly was authorized to restrict use of water in any reasonable way, and accordingly, state authority granted to the town to enact a temporary ban may be found. Without the authority granted by DEQE, however, there would be a serious question as to the police power of Franklin to enact a moratorium without a specific legislative grant. There is no source of independent power to do so. See CHR General, Inc. v. Newton, 387 Mass. 351 (1982); Perry v. Boston Rent Equity Board, 404 Mass. 780 (1989); Marshal House, Inc. v. Rent Control Board of Brookline, 358 Mass. 686 (1971); Boston Teachers Union Local 66 v. Boston, 382 Mass. 553 (1981). The state has now determined that the water emergency no longer exists and has declined to enter a declaration. Accordingly, even if my summary judgment ruling was in error in holding that the moratorium had been improperly adopted, it in any event would have terminated when DEQE terminated the declaration of water emergency.

The plaintiffs have argued that the moratorium also is vulnerable to attack for failure of the town to comply with the provisions of G.L. c. 42, s. 20-23, but these provisions are inapplicable to Franklin which has a town council-town administrator from the town government as provided in the Franklin Home Rule Charter (Exhibit No. 6A.).

The Town claims that it does not have to furnish water if only one or two lots in the subdivision abut a Town way conaining a Town water main. The Supreme Judicial Court already has held that a Town water system or a private utility is required to furnish water to each prospective customer on the same terms as it furnishes to others. In Rounds v. Board of Water and sewer Commissioners of Wilmington, 347 Mass. 40 , 44 (1964), the Court noted, however, that:

. . . [p]rospective customers whose demands for water necessitate extensions of existing systems may stand on a different basis from those whose requirements may be met from immediately adjacent town or water company mains.

Each of the 15 subdivisions in this case directly abuts a Town water main and is now entitled to be supplied with Town water, the declaration of emergency by DEQE having ended. Rounds, however, does not address the situation where other valid governmental concerns limit for the property owner's right to the benefits of the public water supply. I find and rule that a valid declaration of water emergency by DEQE overrides the abutter's right to tie into the existing public water supply in the affected municipality.

The final issue in this case concerns the taking by the Town of property rights of the plaintiffs to which they are entitled to be compensated. A determination of the amount of such compensation has been severed, and no evidence was introduced as to this. There are different standards for determining whether the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution and the due process provisions embodied in the Massachusetts Constitution have been violated. As Justice Nolan has written in Decker v. Black & Decker Manufacturing Co.; Lenox Machine Co., 389 Mass. 35 (1983):

The test under the due process clause of the Federal Constitution is "whether the statute bears a reasonable relation to a permissible legislative objective." . . . Under the State Constitution the issue is whether the statute "bears a real and substantial relation to the public health, safety, morals, or some other phase of the general welfare." . . .

The Second Amended Complaint is grounded only in the Massachusetts Constitution, but whichever standards are applied the legislation even though held invalid in certain respects in this decision, did not constitute a taking. As the Supreme Court of the United States has stated, "whether the action is inverse condemnation and compensable or not does not depend on the validity of the legislative action." See First English Evangelical Church of Glendale v. County of Los Angeles, 107 S. Ct. 2378 (1987); Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 107 S. Ct. 3141 (1987). Compare A. A. Profiles, Inc. v. City of Ft. Lauderdale, 850 F.2d 1483 (11 Cir. 1988). The Massachusetts Courts have been slow to find a taking upon the imposition of regulatory controls so long as any permissible use remains of the property. Turnpike Realty Co. v. Dedham, 362 Mass. 221 , 234-235 (1972); Loveguist v. Conservation Commission of Dennis, 379 Mass. 7 , 20 (1979). The plaintiffs failed to show that they were unable to use their land for any purpose because of the imposition of the various by-law constraints by the Town of Franklin. It is true that the development plans had to be revised to include the drilling of wells and the installation of septic systems rather than the contemplated tie-in with the municipal facilities. Two lots were so designed that it may be impossible to locate both the well and septic system thereon, but there is no showing that the subdivision may not be amended to change the original lot lines. Similarly, in at least two instances, wells have not been successfully drilled or tie-ins authorized where they were pre-existing, but in at least one case an administrative appeal to exhaust administrative remedies would appear to have been an appropriate course of action. Lovequist makes clear that the potential loss of income does not give rise to due process protection. On all the evidence, therefore, I find that plaintiffs are not entitled to recover damages from the defendants.

Judgment accordingly.

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 3

Exhibit 4

Exhibit 5

Exhibit 6

Exhibit 7

Exhibit 8

Exhibit 9

Exhibit 10

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] By Summary Judgment dated January 30, 1989 the Court found the Water Main Amendment to be inconsistent with the provisions of the Subdivision Control Law, G.L. c. 41, ss. 81K-81GG and therefore invalid.

[Note 2] By said Summary Judgment of January 30, 1989 the Moratorium also was deemed invalid since it was not adopted in accordance with Article II, ss. 4-7 of the Town's Home Rule Charter. This judgment also rendered moot the contention of the plaintiffs that the Moratorium was arbitrary and capricious and was applied in an arbitrary and capricious fashion. As will hereafter appear, however, the Court agreed to decide the questions as to the Moratorium if adopted as a by-law.

[Note 3] General Laws chapter 40A, s. 6 now provides in part:

If a definitive plan, or a preliminary plan followed within seven months by a definitive plan, is submitted to a planning board for approval under the subdivision control law, and written notice of such submission has been given to the city or town clerk before the effective date of ordinance or by-law, the land shown on such plan shall be governed by the applicable provisions of the zoning ordinance or by-law, if any, in effect at the time of the first submission while such plan or plans are being processed under the subdivision control law, and, if such definitive plan or an amendment thereof is finally approved, for eight years from the date of the endorsement of such approval, except in the case where such plan was submitted or submitted and approved before January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, for seven years from the date of the endorsement of such approval. Whether such period is eight years or seven years, it shall be extended by a period equal to the time which the city or town imposes or has imposed upon it by a state, a federal agency or a court, a moratorium on construction, the issuance of permits or utility connections.

[Note 4] I have been unofficially informed that the moratorium has now ended, but apparently a decision on the power of the Town to enact it is still wanted.