This cause came on to be heard on Plaintiffs' Motion for an Order of Contempt alleging certain violations of an Interlocutory Order issued by this Court pending the resolution of issues in supplemental registration Case No. 314-S. [Note 1]

On April 27, 1982, after hearing, this court issued an Interlocutory Order ("first injunction"). The form and content of the first Injunction were framed after a hearing and conference with counsel for the parties, during which recommendations were received. The first injunction, by its terms, restrained and enjoined Acapesket Improvement Association, Inc. ("Acapesket") its present and future officers and members, together with their invitees and guests, from going on to any of the property described therein, pending a hearing on the merits. The restricted area was described as follows:

Beginning at a point at the northwest corner of Lot E7 on the easterly sideline of Vineyard Street

Thence turning and running south 58°00' 00" E about 407' to the mean high water line (1979)

Thence running southwesterly and southerly along the mean high waterline (1979) to a point in the easterly side of a stone jetty

Thence turning and running southerly along the easterly side of said jetty about 31'

Thence turning and running on a curve to the right with a radius of 40' for a distance of about 56' to a point in the easterly sideline of Vineyard Street.

Thereafter, on or about June 25, 1982, the plaintiffs erected a split rail fence consisting of posts and rails delineating what the plaintiffs considered to be the boundary over which those named in the injunction were enjoined from crossing. After a prior view by this court on July 26, 1982, and a hearing on August 2, 1982, this court ordered the rails between the posts to be removed and also, that the posts should remain to delineate "the" boundary over which the defendants should not cross ("second injunction").

Subsequently, plaintiffs brought a Motion for an Order of Contempt alleging the following:

1. On or about June 24, 1982, the Association destroyed hedges at the home of the plaintiff, Helen Gottlieb.

2. On or about July 23, 1982, the defendant Association damaged floodlights at the home of the plaintiff, Helen Gottlieb.

3. In compliance with the Order of this Court entered on August 2, 1982, requiring the plaintiffs to remove the fence rails along the disputed beach boundary, said fence rails were removed by the plaintiffs on August 4, 1982. Subsequent to the removal of the fence rails, the Association tore out the remaining fence posts on August 5, 1982.

4. The defendants have continued to violate the preliminary injunction dated April 27, 1982, by sitting on the beach property in front of the homes of the plaintiffs except for the period of time that the Court was present taking a view.

The plaintiffs' motion sought an order citing the Association and John Mitchell, President; John Sweeney, Treasurer; Marvin Hill, Clerk; Albert Lazuk and other unnamed members for contempt. It sought, as sanctions, 1) a fine in the amount of $1,000.00 per day from April 27, 1982; 2) counsel fees; and 3) certain costs for repair of the plaintiff Gottlieb's property. [Note 2]

Sixteen days of trial were held on the motion at which a stenographer was sworn to record and transcribe the testimony. Sixteen witnesses testified and thirty-four exhibits were introduced into evidence. Said exhibits are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. Based on all of the evidence I find and rule as follows:

To constitute a violation of an injunction there must be a clear and unequivocal command and an equally clear and undoubted disobedience. See United Factory Outlet, Inc. v. Jay's Stores, Inc., 361 Mass. 35 , 36 (1972). The burden of proof of such a violation is on the moving party. U.S. Time Corp. v. G. E. M. of Boston, Inc., 345 Mass. 279 (1963).

When both the first and second injunctions are construed together the location of the southeasterly boundary, over which the named defendants were enjoined from crossing, becomes ambiguous. The southeasterly boundary in the first injunction was described as "the mean high waterline (1979)". The injunction itself however was issued in 1982. The waterline of the disputed area is subject to constant change, so that it is improbable that the 1979 mean high waterline was the same as the 1982 mean high waterline. [Note 3] Moreover, the plaintiffs failed to show by a preponderance of the evidence where the 1979 waterline was located in 1982. The second injunction ordered that certain posts erected by the plaintifffs should remain on the disputed area to delineate "the" boundary over which the defendants were enjoined from crossing. A reasonable interpretation of that order would be that the most easterly post, which was approximately twenty feet from the water, demarked the northeasterly corner of the disputed area and the 1979 mean high water line. Another equally reasonable interpretation of that order would be that the posts only delineated one of the boundaries, namely the northeasterly boundary, and that the last post was not intended to demark the northeasterly corner of the disputed area. The fact that the second injunction is susceptible to two equally reasonable and yet conflicting interpretations renders that order ambiguous. Due to the difficulty in indentifying the location of the boundaries described in the orders and the ambiguity created by the second injunction, I rule that the two injunctions do not constitute a clear and unequivocal command. I therefore rule that the defendants cannot be found to be in contempt of the injunctions at issue for crossing onto the disputed area. The evidence disclosed that on occasion certain members of the Association walked and sat within the restricted area. However, in view of the difficulty of lay persons being able to accertain with accuracy the precise location on the ground of the southeasterly boundary of the restricted area, the court finds and rules that the defendants were in substantial compliance with the first injunction. [Note 4]

The first injunction also required that Acapesket and its present and future officers give notice of that order to the members of Acapesket by including a copy of the same in a newsletter or other notice to be issued to the Association's members within a reasonable time. I find that the officers did in fact give such timely notice in compliance with the order. I find further that Acapesket, through its officers, attempted to insure compliance with the first injunction by hiring two beach attendants and directing them to monitor the entrance of the beach and inform members not to use the disputed area. Acapesket also informed its members of the second injunction, urging compliance with it as well as the first injunction. I rule that the movant has failed to show by a preponderance of the evidence that there was a clear and undoubted disobedience of either injunction, and therefore, the plaintiffs' motion for an order of contempt is denied.

Both Acapesket and Albert Lazuk submitted separate requests for findings of fact and for rulings of law. In view of the findings I have made, I decline to rule on Acapesket's or Albert Lazuk's requests for findings of fact. Acapesket's request for rulings of law numbers 3, 4, 5, 16, and 17 are allowed; request number 18 is denied; request numbers 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, and 15 are general principles of law, and although correct as stated, are not requests for rulings of law, and are therefore denied; request numbers 11 and 12 have been rendered moot by plaintiffs' waiver of paragraphs 1-3 of their motion, and therefore, I decline to rule on them. All of Albert Lazuk's requests for rulings of law are allowed.

The plaintiffs' motions for an award of attorneys' fees and expenses are denied.

Judgment to enter in accordance with this Decision.

This action involves the registration of, and rights in, a barrier beach [Note 1] on Green Pond in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable. More specifically, this case involves complex issues of accretions to and erosions from registered land, together with prescriptive rights thereon. The four original petitions in this proceeding were filed pursuant Mass. Gen. L. Ch. 185, §114, alleging ownership of certain land (a portion of the locus) by way of accretion to plaintiffs' registered property and through amended petitions, in the alternative, ownership of said land by way of adverse possession. The defendant, Acapesket, alleges ownership of the entire locus by way of accretion to its registered property and through their responses to the amended petitions, as affirmative defenses, ownership by way of adverse possession, or that they have obtained a prescriptive easement to substantially all of the locus. [Note 2] Three persons intervened as party defendants claiming a prescriptive easement over substantially all of locus. Pending the resolution of issues, a preliminary injunction was issued by the Court restraining and enjoining the defendant, its present and future officers and members, and their invitees and guests from going on any part of the locus in front of the plaintiffs' premises.

Eight days of trial were held on the merits, at which a stenographer was sworn to record and transcribe the testimony. Eleven witnesses testified, including two geological experts specializing in oceanographies, one introduced by plaintiffs and one by Acapesket. Sixteen exhibits were accepted into evidence, including a title examination of the locus and a surveyor's plan of the area. Said exhibits are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. Based on all of the evidence I find and rule as follows:

1. Plaintiffs Samuel Lorusso and Judith Lorusso are owners of certain land in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, described in Certificate of Title No. 89831 and described in said Certificate as lot E-7 on Land Court Plan No. 314-H. [Note 3] The Lorussoes were substituted for the original owner of, and petitioner for, lot E-7, Helen B. Gottlieb, when the lot was sold to them by Mrs. Gottlieb during the pendency of this action.

2. Plaintiffs Lawrence Francis O'Donnell and Frances Marie O'Donnell are owners of certain land in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, described in transfer Certificate of Title No. 29120 and described in said Certificate as lot E-8 on Land Court Plan No.

314-H.

3. Plaintiff Elaine Nasrah, Trustee of L & E Realty Trust, is the owner of certain land in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, described in Certificate of Title No. 76988, and described in said Certificate as lot E-9 on Land Court Plan No. 314-H.

4. Plaintiff Ben Wells is the owner of certain land in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, described in Certificate of Title No. 54676, and described in said Certificate as lot E-10 on Land Court Plan No. 314-I.

5. Defendant, Acapesket Improvement Association, Inc. (Acapesket), is the owner of certain land in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, described in Certificate of Title No. 78735, consisting of five parcels. Parcels two and three in said Certificate are shown on Land Court Plan No. 314-H as lot E-3 and lot E-4, which abuts the locus. Parcel four, which is of primary importance in this litigation, is described as "including the sand bar, (and) any and all land remaining in Certificate of Title No. 702 (except Lot 335) when new certificate after death was issued."

6. The Certificate of Title which immediately precedes Certificate of Title No. 78735 in Acapesket's chain of title is No. 9356, and includes no reference to "including the sand bar." The deed which conveyed certain property out of Certificate No. 9356 and into Acapesket was prepared by one of Acapesket's previous counsel. That deed contained the reference to "including the sand bar." The reference to the sand bar was also included on Certificate No. 78735, subsequent to its original issuance, at the request of Acapesket's counsel. Land Court approval was not obtained to amend or correct the Certificate but rather Acapesket's counsel instructed the Registrar by letter to make the change to the Certificate in July of 1979.

7. The intervenors/defendants, Marjorie Halloran Connelly, Priscilla Halloran O'Connell, and Katherine Halloran Sullivan, are co-owners of property at 6 Vineyard Street, Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable, which is in the Acapesket area near the locus.

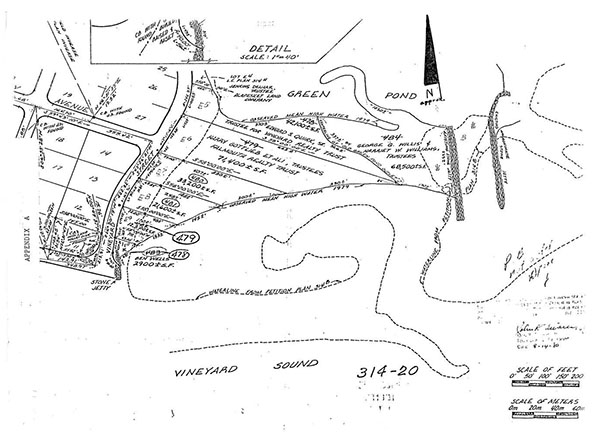

8. The locus is a barrier beach [Note 4] located at the southerly end of Green Pond in Falmouth, in the County of Barnstable. This barrier beach is reflected on Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20 as a land mass bounding on lots E-5 through E-10. [Note 5] The plaintiffs are claiming a portion of the land mass as accretions to their registered lots E-7, E-8, E-9 and E-10. The land they are claiming is shown on Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20 as lots 478, 479, 480 and 481. [Note 6] The defendant, Acapesket, is claiming the entire barrier beach, shown as lots 478, 478, 479, 479, 480 and 484 on Plan No. 314-20, as accretions to its registered "sand bar".

9. Plaintiff Ben Wells' lot E-10 is described in his Certificate of Title No. 42938 as having the following boundaries: "Northeasterly by Lot E-9, sixty-three (63) feet ; Southeasterly by land now or formerly of Thomas Malchman, et al, eighty and 61/100 (80.61) feet ; Southerly by Ocean Avenue ten and 49/100 (10.49) feet ; and Southwesterly by the junction of Ocean Avenue and Vineyard Street, fifty-eight and 89/100 (58.89) feet and by Vineyard Street, fifty and 29/100 (50.29) feet . . ." No boundary description in the Certificate of Title is listed as abutting Green Pond or Vineyard Sound.

10. The southeast boundaries of plaintiffs Elaine Nasrah, Samuel Lorusso and Judith Lorusso, and Lawrence Francis O'Donnell and Frances Marie O'Donnell's lots are all described in their Certificates as abutting Green Pond. These lots are all also subject to a restriction that no buildings may be constructed on said lots.

11. Lots E-7 through E-10 are all vacant lots on the easterly side of Vineyard Street. All of the plaintiffs own a corresponding lot on the opposite side of Vineyard Street, on each of which a house is situated.

12. Parcel four in Acapesket's Certificate of Title derives from Certificate of Title No. 702, which was issued in 1902. Contained in Certificate No. 702 was so-called "Lot-A" as depicted on Land Court Plan No. 314-B, sheets 1 and 2. "Lot A" is described in Certificate No. 702 as including the plaintiffs' lots along with "the sand bar and lands adjoining Green Pond outlet on the west." As Plan No. 314-B, sheet 2 shows, the land in the area of the Green Pond outlet in 1902 included a hook-shaped 200 foot wide peninsula extending out approximately 750 feet from the westerly shore of Green Pond. Certificate No. 702 also contained another sand bar described therein and shown as part of "Lot B" on Plan No. 314-B, sheets 2 and 3. This sand bar extended westerly from the east side of Green Pond. Certificate No. 702 also described lot B as containing certain "islands near the shore."

13. As depicted on Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20, by 1979 the original location of these two 1902 sand bars was almost completely covered by the open waters of Vineyard Sound. An exception to this is that the location of the 1902 lot B islands is currently occupied by a portion of the locus claimed by Acapesket. This is depicted as a dotted circle to the west of the current Green Pond Outlet on Plan No. 314-20.

14. In 1902, what was to become lot E-10 had no boundaries on either Vineyard Sound or Green Pond. The land which would become lots E-5 through E-9 was bounded on the east by Green Pond.

15. In 1925, Land Court Plan No. 314-H was filed showing the subdivision of "Lot A" into the "E-lots," (excluding lot E-10). At that time, lots E-5 through E-9 were bounded on the east by Green Pond.

16. In 1926, Land Court Plan No. 314-I was filed showing the further subdivision of lot E-10. At that time, lot E-10 was completely bounded on the east by the west-side sand bar.

17. In 1925, the northerly side of the west-side sand bar had migrated north approximately 150 feet of its original 1902 position. In 1926 the southerly shore of this west-side sand bar was approximately 200 feet south of the southerly boundary of lot E-9. The southerly shore of the 1902 west-side sand bar was approximately 350 feet south of that boundary. In 1926, as shown on Plan No. 314-I and described in Certificate No. 702, the west-side sand bar was owned by Thomas Malchman.

18. Both the west-side and the east-side sand bars were from 1926 until 1947 slowly migrating in a northerly direction as a result of erosions on their southerly boundaries and by corresponding accretions on their northerly boundaries.

19. In 1943, the west-side sand bar was bounding in whole or in part on what had been the 1926 easterly boundary of Lots E-7 through E-10. In 1943 the 1902 Lot B "islands near the shore," had either ceased to exist entirely or, through a combination of accretion to the east-side sand bar and accretion to the "islands near the shore," these two land masses had joined forming one east-side sand bar on lot B of Certificate No. 702. And, from 1902 until 1943, the location of the Green Pond inlet, on the northerly side of the two sand bars, had not substantially changed its position, but through the process of accretion to the west-side sand bar and erosion on the east-side sand bar, there had been a slight eastward migration of the inlet.

20. In 1947, both sand bars had migrated further north, with the result that the west-side sand bar was now on what had been the 1925 boundary of lots E-7 through E-9 entirely, and lot E-10 was bounding on Vineyard Sound. Land Court Plan No. 314-I shows the west-side sand bar bounding on lot E-10, but not on any of the other "E" lots. The northerly end of Green Pond inlet was in substantially the same location as it was in 1943, but it had migrated slightly in a easterly direction.

21. The southerly side of Green Pond inlet, from 1902 to 1947, tended to shift slightly from east to west depending on various natural and man-made influences. Those man-made influences were the result of a groin installed by the state in 1947 on the westerly boundary of lot E-10 and extending in to Vineyard Sound.

22. Immediately prior to 1950, the west-side sand bar was still bounding on lots E-7 through E-9. At that time, the west-side sand bar had attached to it a large "flood tidal delta" on the eastern most side of its northerly boundary, and that "flood tidal delta" [Note 7] marked part of the westerly side of the Green Pond inlet. This inlet will be referred to as the "original inlet."

23. During the year 1950 there were three or four large storms, one or more of which caused a breach in the west-side sand bar that resulted in a new inlet for Green Pond forming in approximately the same location as the 1926 easterly boundaries of lots E-7 through E-9. This inlet will be referred to as the "1951 inlet." This breach caused the inlet to move approximately 800 feet to the west from its location in 1947. From 1902 to 1947 there was only minor inlet migration and, what there was, was in a net, easterly direction.

24. In 1951, the easterly boundary of the west-side sand bar's flood tidal delta was in substantially the same location as it had been in 1950, before the 1951 inlet formed.

25. The 1951 inlet ran north and south, but there was also a branch of this inlet which ran east and west.

26. At some point after the 1950 breach formed the 1951 inlet, but before October of 1951, the old inlet was filled in by accretions to one or both of the two sand bars.

27. During 1952, the Department of Public Works (DPW) cut a new inlet for Green Pond supported by two jetties. The "DPW inlet" was and is located approximately 800 feet east of the 1951 inlet. The northerly side of the DPW inlet was located in substantially the same location as the easterly boundary of the flood tidal delta. Therefore, the DPW inlet is located in substantially the same location as that of the original inlet just prior to the 1950 breach.

28. As the DPW was dredging the new inlet, it was dumping the resulting spoil off of what was in essence the old west-side sand bar. [Note 8] The DPW began dumping the spoil off of the eastern end of the old west-sides and bar's southerly boundary and continued dumping in a westerly direction. When the DPW had dumped spoil up to the boundary of lot E-10, the DPW began dumping in a northerly direction until the 1951 inlet was filled in. This dumping or filling resulted in the substantial formation of the locus.

29. It has not been established by any party that the spoil dumped was a necessary aid to navigation, and therefore, I find that it was only incidental to the primary purpose of the two new jetties and new DPW inlet.

30. Priscilla Halloran O'Connell, Marjorie Halloran Connelly, Katherine Halloran Sullivan, and various members of their families as well

as friends used most portions of the locus for recreational beach purposes from 1952 to 1982 during the months of June through October. The locus's literal boundary, however, shifted in and out over most of that period, so that the above individuals could not have used the entire locus for over twenty years. The above parties initially entered the locus at the corner of Ocean Avenue and Vineyard Street, but at some point began entering at the corner of Bayview Avenue and Vineyard Street, so that no one entrance was used consistently for twenty years.

31. The owners of lots E-7 through E-10, at least from 1962 until 1984, used the sandy area in front of their respective lots seasonally for recreational beach purposes. The locus includes the sandy area so used.

32. The Gottliebs seasonally used the sandy area in front of lot E-7 for recreational beach purposes from 1955 until 1981.

33. Three split rail fences were constructed on lot E-8, one on its Vineyard Street boundary, one on its southerly boundary and one on its northerly boundary, in 1962 by the O'Donnells. The fence on the southerly boundary extended approximately thirty feet towards the water from Vineyard Street and the fence on the northerly boundary extended approximately fifty feet in the same direction.

34. The Gottliebs from 1955 to 1981, and the O'Donnells from 1962 to 1982, would from time to time request uninvited, unidentified individuals to leave the sandy area in front of their respective lots.

35. The Gottliebs acquiesced in members of the Acapesket Improvement Association using the sandy area in front of lot E-7 from 1955 until 1981 for recreational beach purposes.

36. Members of the Acapesket Improvement Association used the sandy area in f ront of lot E-6 for recreational beach purposes by way of an express agreement with the owner of that property.

37. George G. Willis, Trustee and Harriet W. Williams, Trustee received notice of this action, did not file any appearances, and were defaulted by way of a general default.

The locus in this case is a barrier beach located in Falmouth in the County of Barnstable. As shown on Plan No. 314-20, plaintiffs' are seeking to establish ownership of lots 478, 479, 480 and 481. The plaintiffs are claiming ownership to this land through accretion to their existing registered land. The defendant, Acapesket, is likewise claiming ownership of the aforementioned lots and also lots 479, 478, and 484 [Note 9] through accretion to its existing registered land.

In order to reach a better understanding of this case, a review of legal principles regarding property rights of riparian land owners on navigable waterways will prove helpful. We start with the well-settled principle that when the boundary between the water and the land changes by the gradual deposit of alluvial soil, then the line of ownership follows the changing waterline. Michaelson v. Silver Beach Improvement Association, Inc., 342 Mass. 251 , 253-54 (1961). These accumulations are referred to as accretions and one must be a litoral land owner to acquire an interest in them . A litoral land owner is one who has title to land bounded by the ocean or an extension of the ocean. Land is bounded by the ocean if it extends either to the high or the low water mark. See Allen v. Wood, 256 Mass. 343 , 347-51 (1926) (determining that litoral land owner with right only to high water mark may acquire rights in accretions).

A litoral owner can acquire ownership of accretions caused by either natural processes or by human intervention, so long as the accretions are not caused by the litoral owner himself. Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 254. Under certain circumstances the state will be deemed to be the owner of accretions it has created. For example, when a governmental body creates a channel to improve navigation, and in the process fills the land along the shore to aid in navigation, then the state will be the owner of that newly created land, if and only if, there is a finding that there is a substantial and reasonable connection between the newly created land and the improvement in navigation. The new litoral land must be a necessary aid to navigation. See Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 256-57.

Just as a litoral land owner may find his land enlarging through the gradual process of accretion, he may also find his land dwindling through the gradual process of erosion. The same principles that apply to accretions apply to erosions. Litoral boundaries move in and out with the gradually changing water line. Individuals who purchase litoral property have an expectation that their litoral boundary will be affected by erosions and accretions. Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 258. The key is that the changes are gradual, when the change is drastic or catastrophic, then a different rule will apply.

Under the rule or doctrine of avulsion, which is followed by the great majority of jurisdictions, when a sudden or drastic change occurs in the boundary of a navigable body of water, then the boundaries of the abutting literal land do not change. The boundaries will remain wherever they were just prior to the avulsion. Kitteridge v. Ritter, 172 Iowa 55, 57, 151 N.W. 1097, 1097 (1915) ; Durfee v. Keiffer, 168 Neb. 272, 276-77, 95 N.W. 618, 623 (1959) ; Wychoff v. Mayfield, 130, Or. 687, 690, 280 P. 340, 341 (1929). This process commonly occurs where a river permanently abandons its original bed in favor a new and distinctly different one. See Durfee, 95 N.W. at 224. It should be noted, however, that there is a presumption that when a literal boundary changes, it is due to an accretion rather than an avulsion. See Kitteridge, 172 Iowa at 59, 151 N.W. at 1098 and cases cited therein.

When new land forms through the process of accretion there may be a conflict between two abutting litoral land owners as to who owns the new land. When accretions occur they not only change the position of the litoral boundary, but generally also change the length of that boundary due to the fact that most litoral boundaries are irregularly shaped. When two or more litoral owners both have a right to newly formed accretions the doctrine of equitable division will determine what rights each owner has in the accretions. Burke v. Commonwealth, 283 Mass. 63 , 67 (1933) ; Allen v. Wood, 256 Mass. 343 , 256 (1926). As the name of the doctrine implies, it is an equitable doctrine. No set rules for division are possible due to the infinite variety of circumstances which may arise when dealing with the formation of accretions. In determining the proper division of accretions, a major factor to be considered is that "[t]he litoral or riparian nature of property is often a substantial, if not the greatest, element of its value." Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 256. Therefore, "[t]he object of apportioning accretions is that they shall be so apportioned as to do justice to each owner, in the absence of a positive prescribed rule and of direct judicial decision to guide, and their division on a non-navigable river frontage is so made as to give each relatively the same proportion in his ownership of the new river line that he had in the old." Allen, 256 Mass. at 350 (case involving accretions to litoral land).

With these principles in mind, I now move to a consideration of the law as it applies to the facts in this case.

The facts indicate that the west-side sand bar, in 1926, was owned by Malchman and was registered as such. In 1926, lots E-5 through E-10 were separately owned and registered. At that same time, lots E-5 through E-9 were bounded on the east by Green Pond, while lot E-10 was bounded on the east by the west-side sand bar. What is clear is that from 1902, the time of the original registration, until 1947 there was a constant, slow, imperceptible northward migration of the west-side sand bar. And, by 1947 the west-side sand bar had migrated past lot E-10 and was bounding entirely on lots E-7 through E-9.

In order to understand the legal significance of this migration, one must understand the process by which the sand bar moved. The major factor contributing to the migration was the sea and wind hitting the sand bar on its southern boundary from a northerly direction. This caused an erosion on the sand bar's southern boundary and a corresponding accretion on the northern boundary resulting in a net, northward migration. When said accretions formed, however, they were not only deposited on the west-side sand bar, but also on lots E-9 through E-7. This is due to the fact that the sand bar's northern boundary is approximately at a right angle to lots E-9 through E-7's eastern boundaries. Therefore, the accretions were forming on lot E-9 and the west-side sand bar simultaneously and continuously. [Note 10]

When accretions form on more than one piece of litoral property simultaneously, as has happened in this case, the doctrine of equitable division applies. Therefore, the owners of lot E-9 and the owners of the sand bar would both have some interest in the accretions depending on the percentage of their previous, literal frontage. As the sand bar continued moving north, it accreted more and more on lots E-9 through E-7. With each of these new accretions, the litoral owners would each have an interest in those accretions related to the percentage of their previous litoral frontage.

The next and more difficult issue concerns the legal effect of the erosions associated with the northward migration of the west-side sand bar. It is a well established principle of law that erosions on unregistered litoral property result in a loss of the eroded property for the owner. Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 258. If a piece of property erodes completely away, then the owner will permanently lose all interest in it. The issue here is whether the owners of registered property lose their ownership interest in eroding property in the same way that non-registered owners do.

One of the characteristics of registered land is that the boundary descriptions listed in an owner's certificate of title, and shown on their

land court plan, are deemed to be conclusive. Mass. Gen. L. Ch. 185, et. seq.; See Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 260. But see Mass. Gen. L. Ch. 185, §45; Kozdras v. Land/Vest Properties, Inc., 382 Mass. 34 (1980). One challenging the boundaries of a registered parcel cannot successfully go behind a Certificate of Title to show that the boundary descriptions are other than what is described in it. The boundaries of all litoral property, however, frequently change, so that the actual boundaries will rarely correspond exactly with what is depicted on a registered owner's certificate of title or land court plan. Chapter 185, which embodies the registration system, does not explicitly address whether the owners of registered litoral land should be subject to the same common law principles which the owners of non-registered litoral land are. It, however, becomes apparent what the Legislature must have intended with regard to the rights of registered owners of litoral land when those rights are contrasted with the rights of the state in navigable waterways.

Owners of litoral land bounded by the sea own from mean high water to mean low water, but not more than 100 rods from mean high water, in fee, subject to the rights of the public for navigation, fishing and fowling. Opinions of The Justices, 383 Mass. 890 , 900-06 (1981) ; Boston Waterfront Development Corp. v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 , 630-43 (1979). The Commonwealth holds title to the area below mean low water in trust for the public's benefit. Id. The Commonwealth may grant rights to private entities in the area below mean low water, as for example where rights are granted to construct wharves to aid in navigation. Id. The ability of the Commonwealth to grant such rights, however, is limited by the condition that any such grants may only be made to fulfill a public purpose. Boston Waterfront Development Corp., 378 Mass. at 646-54; U.S. v. 1.58 Acres Of Land Situated In the City of Boston, County of Suffolk, Commonwealth of Mass., 523 F. Supp. 120, 124 (D. Mass 1981). The Commonwealth could not grant any rights below mean low water, through the registration system or otherwise, in private entities for non-public purposes. Therefore, the fact that litoral land is registered, does not alter the common law effect which erosions have on literal land.

The next issue involves what rights a registered land owner can maintain in new accretions when said registered land no longer abuts any point on the ground which was originally granted. It seems only logical and equitable that when a land owner's property is eroding on one side, and forming accretions on another, in order to maintain an interest in new accretions, there must always remain one point fixed on the ground which is described in the original grant of property. To follow another rule would permit someone to maintain a property interest in land which could conceivably migrate hundreds of yards, or more, from its original location. This rule would obviously be inconsistent with conventional concepts of property law which set boundaries for real property at fixed points on the ground. [Note 11] Under the former rule then, in 1947, when the west-side sand bar no longer abutted lot E-10, that being the most northerly section of its only non-litoral boundary as shown on Land Court Plan No. 314-I, the original owners of that sand bar lost their interest in it. Therefore, I rule that the notation on Acapesket's Certificate of Title No. 78735 which reads "including the sand bar", which was added to said Certificate without Land Court approval, shall be stricken from said Certificate.

The plaintiffs have raised several arguments as to why the west-side sand bar should not be included within Acapesket's Certificate of Title. In view of the fact that I have found that by 1947 the sand bar had eroded away to the point where Acapesket's predecessors lost all interest in it, I decline to rule on plaintiffs' other arguments.

At the point when the west-side sand bar began moving past lot E-10, part of lot E-10 bounded on the ocean. And, when the sand bar no longer bounded on lot E-10 at all, then lot E-l0's entire eastern boundary was on the ocean. The issue raised by this phenomenon is, whether a non-litoral, registered lot owner acquires the rights associated with a litoral owner when an abutting, litoral, registered lot erodes completely away. The fact that both lots are registered lots should not affect the owners' common law rights as litoral property owners. At common law, as well as with registered lots, if property erodes completely away then the owner of that lot loses all interest in the land. [Note 12]

At the point when the original litoral lot completely eroded away, the original non-litoral lot bounded on the ocean. The issue then becomes, what rights does that lot owner have in any new accretions which might form on the new litoral boundary, and also in the flats bounding on the lot. There are three possible parties which could conceivably have rights in any new accretions: (1) the old owner of the original litoral lot; (2) the state; or (3) the lot owner with the new litoral boundary. Accretions are by definition new land, the original lot is not simply reappearing. Therefore, the original lot owner can have no interest in any new accretions. It is the physical character of litoral land which gives rise to the owner's common law rights, not the conveyance by the lot owner's grantor. Therefore, if a non-litoral lot owner acquires a boundary on the ocean that lot owner should, at the same time, acquire all the rights associated with a litoral lot owner, despite the fact that the original grant of property did not convey such rights. It follows then that the state would not acquire ownership of any new accretions or in the flats abutting the litoral boundary. I therefore rule that in 1947, at the point when the west-side sand bar no longer abutted lot E-10, lot E-10 became a litoral lot with all rights associated therewith.

In 1947, the west-side sand bar abutted lots E-7 through E-9. At that point, those registered lot owners each owned a portion of the sand bar. The easterly end of the west-side sand bar and the flood tidal delta attached to it marked both the Green Pond inlet and the eastern boundary for lots E-7 through E-9 at that time. By 1950, the west-side sand bar was in substantially the same position as it was in 1947. In 1950, there were three or four large storms, one or more of which caused a breach in the west-side sand bar in approximately the same location as the 1926 easterly boundaries of lots E-7 through E-9. This breach caused a new inlet to form. This new inlet was approximatley 800 feet west of the "original inlet". Although from 1902 until 1950 the sand bars had migrated substantially north, the relative position of the inlet vis-a-vis the west-side and east-side sand bars had changed very little in that time. The sudden formation of this new inlet in a drastically new location is closely analogous to the situation where a river permanently abandons its bed in favor of a distinctly new and different bed. I find and rule that this geological phenomenon is factually and legally an avulsion. I rule that the two following factors overcome the presumption that a change in the position of a waterway is deemed to be caused by accretions as opposed to an avulsion. Firstly, that Green Pond inlet had migrated east or west only minor distances for forty-eight years, and that in one year it moved approximately 800 feet to the west, and secondly, that there were four large storms in that same year of sufficient intensity to cause a breach in the west-side sand bar.

The legal result of an avulsion causing the new inlet to form is that the original Green Pond inlet, which was the pre-avulsion boundary of lots E-7 through E-9, remained the boundary of those lots after the avulsion. The approximate location of the inlet prior to the avulsion can be determined by the location of the eastern portion of the flood tidal delta. In 1952 the DPW cut a new inlet for Green Pond and installed two jetties to support it. In examining the November 1951 plan drafted by the DPW for the proposed new Green Pond inlet, the flood tidal delta can be seen. One can infer that from the time of the avulsion in 1950 until the DPW plan was drafted in 1951, there was little change in the location of the flood tidal delta. The plan reflects that the northern side of the DPW inlet was to be in substantially the same location as the eastern boundary of the flood tidal delta. Therefore, at least as to the northern side, the DPW inlet and the original inlet just prior to the avulsion were in substantially the same location. I therefore rule that the DPW inlet shall be used as a monument to demark the extent of the eastern boundary of the west-side sand bar.

When the DPW dredged the DPW inlet, it dumped the resulting spoil off of the old west-side sand bar beginning on the eastern side of its southern boundary, and filled in a westerly direction until they reached the southernmost portion of the 1951 inlet. At that point, they began dumping spoil in a northerly direction until the 1951 inlet was completely filled in. Because I have found that all accretions (spoil) resulting from the DPW dredgings were only incidental to, and not necessary for, the primary purpose of the DPW inlet, all of said accretions must, therefore, become the property of one or more of the literal owners. When the dredging and dumping was finished there were accretions as far north as lot E-4. The dumping, or accretions, which occurred up to the northern most section of lot E-7's eastern boundary were accretions from one piece of the E-7 through E-9 lots to another. [Note 13] That is, the west-side sand bar connected to the rest of the registered lots across the inlet.

After the dumping of spoil had progressed past lot E-7, however, the accretions were moving primarily south to north, filling in the inlet in front of the other E lots in much the same way as the west-side sand bar did when it migrated north. At that point, all accretions past lot E-7 are accretions to both lots E-6 through E-4 and the ever expanding west-side sand bar. When accretions form on more than one piece of property the doctrine of equitable division applies. When applying equity, the facts must be examined in their totality.

The predominant accretions which occurred in 1952 were due to the DPW dumping spoil. While under Massachusetts law this type of activity is deemed to be an accretion, it nevertheless occurs in a relatively short period of time. In this case it took approximately one year to fill most of the locus. Moreover, the area to be filled was intended to be filled as one unit. The fact that the procedure used to dump the spoil required that the dumping begin at one point and move to another should not affect the legal result. So then, I rule the most equitable point in time to consider division of the accretions is at the completion of all dumping. I further rule that the most equitable way to maintain the pre-accretion, litoral frontage for each lot owner is to extend their northerly and southerly lot lines to Vineyard Sound or Green Pond as the case may be. This is the division as reflected in Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20, with one notable exception.

Plaintiffs' plan also reflects that George G. Willis and Harriet W. Williams, Trustees, are the owners of lot 484. This is presumably due to an assumption made by the surveyor that Green Pond inlet was located west of the DPW inlet jetties prior to the geological activity in the early 50's. However, as I have found, the original inlet was located in substantially the same location as the DPW inlet just prior to the avulsion. This being the case, I rule that the above-mentioned parties have no interest in lot 484. Therefore, Plaintiffs' Plan must be revised

in accordance with this decision. Before Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20 can be approved by the Land Court, the plaintiffs' surveyor must satisfy the Land Court Engineering Division regarding any changes in the locus subsequent to the filing of the Plan.

A simplified scenario of the geological activity in the area of the locus and the legal result of that activity on the abutting land owners can be stated as follows:

1. A registered sand bar or barrier beach, not owned by the plaintiffs, migrated over a period of years so that it no longer abutted any point shown on the Land Court Plan depicting the sand bar's original boundaries. When this occurred, the original owner of the sand bar permanently lost his interest in it due to erosions. As the sand bar migrated it was actually accreting onto other independently owned, registered, litoral lots, some of which were owned by the plaintiffs. Those other lot owners acquired an interest in the sand bar as it accreted onto their land.

2. In 1950, there were several storms which breached the sand bar, resulting in a new inlet forming. This type of violent geological activity is referred to as an avulsion. When an avulsion occurs, an abutting owner's litoral boundary will remain where it was prior to the avulsion. The boundary does not follow the changing waterline as it does in the case of erosions or accretions.

3. In 1951, the DPW dredged a new inlet in approximately the same location as the pre-avulsion inlet. The spoil from the dredging was deposited off of the sand bar, filling in the area which is now substantially the locus. That filled area is an accretion, and whoever owns the litorall and where it formed owns some portion of the new land.

The next claim to be addressed is whether the intervenors have acquired a prescriptive easement to use the locus "for all purposes for which a bathing beach is used." The land over which the intervenors seek a prescriptive easement is registered land. By statute in this Commonwealth, no right can be acquired by adverse or prescriptive use in registered land. Mass. Gen. L. Ch. 185, §53. The issue to be resolved here is whether a prescriptive easement may be acquired by adverse use in accretions to registered land before the Land Court amends the registered land holder's Certificate of Title to reflect the new accretions.

At common law, a litoral land owner acquires title to accretions as they are deposited on their property. The line of ownership follows the changing waterline. Michaelson, 342 Mass. at 254. A court decree is not required to vest title to the accretions in the litoral owner. This principle of law alone should be sufficient to rule that no rights may be acquired by adverse use in accretions forming on registered land.

The construction of the Certificates of Title for the plaintiff' lots, however, further support this ruling. [Note 14] In examining the Certificates of Title for lots E-7, E-8, and E-9, the southeasterly lot lines are described as "by Green Pond" and the northeasterly and southwesterly lot lines are described in terms of bounding by lots and also by specific distance measurements. The boundary descriptions are modified by a

recitation that "all of said boundaries, except the water line, are determined by the Court to be located as shown on subdivision plan 314-H. . ." (emphasis added). The Land Court does not determine the location of water lines because of the legal effect that accretions, erosions, and other geological phenomena may have on litoral boundaries. [Note 15] There is no difficulty in determining where the litoral boundaries are in view of the legal doctrine that "[w]henever, in the description of land conveyed by deed known monuments are referred to as boundaries, they must govern, although neither courses, nor distances, nor the computed contents, correspond with such boundaries." Burke v. Commonwealth, 283 Mass. 63 , 67-68 (1933) (quoting Davis v. Rainsford, 17 Mass. 207 , 210). The monument in this case is Green Pond. The Certificates, therefore, allow for the fact that the litoral boundaries are following the changing waterline.

Because at common law accretions became the property of the litoral owners at the time they formed and also because the plaintiffs' Certificates of Title allow for this phenomenon, I rule that the accretions became registered land at the time of their formation. The intervenors' claim for a prescriptive easement over the beach must, therefore, fail. To reach a different result would require that registered land owners amend their Certificates of Title on a regular basis to prevent any loss in their property rights due to adverse use by another. This would be inconsistent with one of the principle purposes of the registration system: "to make titles 'certain and indefeasible'". Michaelson 342 Mass. at 251 (quoting Morchardt v. Dearborn, 313 Mass. 40 , 47 (1943).

Acapesket has also claimed a prescriptive easement over "substantially all the land shown on Plaintiffs' Plan No. 314-20 and all land added thereto by accretion." As to all land shown on Plan No. 314-20, other than the locus, Acapesket has failed to establish a prescriptive easement. As to the locus, I have ruled that that land had become registered property at the time of its formation, and so, any claim for a prescriptive easement over it must also fail.

Judgment accordingly.

SAMUEL LORUSSO, JUDITH LORUSSO, LAWRENCE FRANCIS O'DONNELL, FRANCES MARIE O'DONNELL, ELAINE NAZRAH, Trustee of L & E Realty Trust, BEN WELLS vs. ACAPESKET IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION, INC., et al.

SAMUEL LORUSSO, JUDITH LORUSSO, LAWRENCE FRANCIS O'DONNELL, FRANCES MARIE O'DONNELL, ELAINE NAZRAH, Trustee of L & E Realty Trust, BEN WELLS vs. ACAPESKET IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION, INC., et al.