MOTHER BROOK DEVELOPMENT, INC. v. ALLAN PRAUGHT, et al.

MOTHER BROOK DEVELOPMENT, INC. v. ALLAN PRAUGHT, et al.

MISC 122870

April 6, 1990

Norfolk, ss.

FENTON, J.

MOTHER BROOK DEVELOPMENT, INC. v. ALLAN PRAUGHT, et al.

MOTHER BROOK DEVELOPMENT, INC. v. ALLAN PRAUGHT, et al.

FENTON, J.

The plaintiff, Mother Brook Development, Inc. (Mother Brook), brought this action seeking declaratory and injunctive relief against the defendant, Allan Praught (Praught). Mother Brook is seeking a declaration that a record easement held by Praught, and extending over certain land owned by Mother Brook, has been extinguished. Mother Brook is also seeking to restrain Praught from entering upon or passing over that same land. Praught counterclaimed seeking a declaration that its easement still exists and that the easement has not been extinguished.

Mother Brook moved for the joinder of the Metropolitan District Commission (MDC) as a necessary party; and that motion was allowed. [Note 1] Subsequently, Mother Brook moved for summary judgment and Praught moved to dismiss the complaint. Both motions were denied; whereupon, the case proceeded to trial. A trial was held, at which a stenographer was sworn to take and transcribe the testimony. Three witnesses testified and eleven exhibits were accepted into evidence as well as a stipulation of facts. Based upon the foregoing, I find the facts to be as follows:

1/ The plaintiff, Mother Brook Development, Inc. (Mother Brook), is the owner of approximately 4.75 acres of land (the locus), including a portion of the disputed easement area, located in Dedham, Massachusetts.

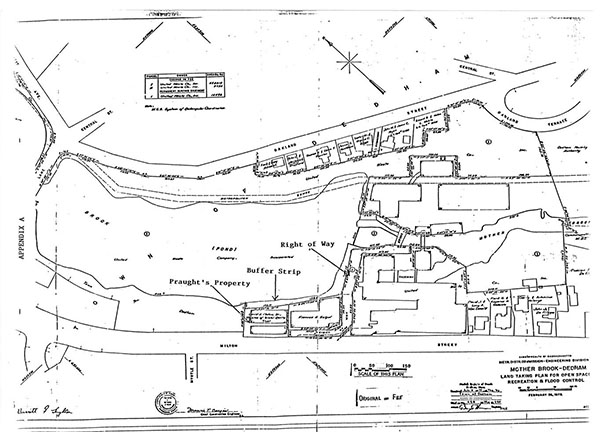

2/ The defendant, Allan Praught (Praught), is the owner of a parcel of land located at 70 Milton Street, Dedham, Massachusetts, which abuts, in part, the locus to the northwest (Praught's property). See Appendix A. [Note 2]

3/ Praught acquired his property by deed dated July 15, 1977, and recorded at Norfolk County Registry of Deeds at book 5357, page 12. [Note 3]

4/ By deed dated November 24, 1937, and recorded at Book 2165, page 245, one of Praught's predecessors in title was granted a non-exclusive easement to "pass and repass for all purposes over" certain land extending from the rear of what is now Praught's property to Milton Street (the easement). In the rear of Praught's property there is a small strip of buffer land (the buffer strip), approximately fifteen feet in width, which separates the property from Mother Brook Pond. The easement extended over that strip of land to a thirty foot wide right of way, (the right of way) then over the right of way to Milton Street. See Appendix A.

5/ The buffer strip and the land over which the right of way crosses were both owned by one of Mother Brook's predecessors in title at the time of the conveyance described in paragraph 4.

6/ Praught has used the easement to gain access to the rear of his property on a daily basis beginning shortly after he acquired the property in 1977 and continuing for approximately seven years. Praught's property has frontage on Milton Street and has a fee interest in a second driveway which gives access to the rear of his property. That driveway has a slope of approximately sixty degrees.

7/ Praught originally used his land, and the easement at issue, in connection with a contracting business he was involved with. He now leases his property for dead storage of construction equipment.

8/ By an Order of Taking dated June 26, 1975 (the Order), the MDC took title to the land described in the Order and shown on a plan incorporated by reference into the Order entitled, "Mother Brook-Dedham, Land Taking Plan For Open Space, Recreation and Flood Control", dated February 26, 1975 (the Plan).

9/ The Order was recorded on July 9, 1975; more than two years prior to Praught's acquisition of his property.

10/ The Order describes three parcels to be taken, two of them in fee and the third for an easement. The Order lists the three parcels separately under the headings "Parcel one", "Parcel two", and "Parcel three". Following the description of each of the parcels is a table with the headings "Parcel", "Owner", and "Area Taken in Square Feet" for the first two parcels and "Area in Square Feet In Which Perpetual Easement Is Taken" for the third. The description under the heading "Parcel" is the designation used on the Plan to demark the three parcels; namely, "I", "II", and "1". See Appendix A.

11/ While the fee owner of the condemned property was given notice of the taking and received compensation for the Taking, Praught's predecessor in title who held the benefit of the easement at the time of the taking, is not shown on the tables in the Order listing owners of the taken property, nor was he given notice of the taking.

12/ Following the description of the third parcel and its corresponding table, there is a separate paragraph which states "[t]here is excepted and reserved to those lawfully entitled thereto a right of way over parcel 1 herein taken as and where now located".

13/ The fifteen foot buffer strip behind Praught's property was described in the Order under the description of Parcel one and was also included in the area shown on the Plan as Parcel I. See Appendix A.

14/ The Order only indicates the taking of a nonexclusive easement over the way as described in the Order under Parcel three and as shown on the Plan as parcel 1. See Appendix A.

15/ Parcel two as described in the Order and as shown on the Plan as Parcel II, does not directly affect the land and rights at issue herein.

16/ That portion of the easement extending over the fifteen foot buffer strip was paved at the time Praught took title to his property in 1977. That portion of the easement extending over the way was a gravel covered road at the time Praught took title to his property.

17/ The MDC had not objected to Praught's use of the buffer strip for access to the rear of his property, up to the time of trial.

18/ During the times when Praught was at his property he never, or rarely, saw any MDC personnel or vehicles in the area surrounding his property or the buffer strip.

19/ The area taken in Parcel one consisted of 498,819 square feet of land, and surrounded and included Mother Brook Pond. A dam is located within the area designated Parcel one, and is also located approximately 145 feet from the edge of the buffer strip. Beginning in the 1970's, the MDC did maintenance work on the dam and in substantially all of the area around the perimeter of Mother Brook Pond. It, however, was not established at trial whether the MDC did any work directly on the fifteen foot buffer strip behind Praught's property.

The pertinent facts, and the issues raised thereby, may be summarized as follows. Prior to the MDC's Taking, the individual who owned Praught's property had, as an appurtenant right, the benefit of an easement. That easement was granted to pass and repass for all purposes over a fifteen foot buffer strip of land extending from the rear of Praught's property to a thirty foot way, and then over that way to Milton Street. The MDC made a taking of three parcels. The Order of Taking described the first parcel as being taken in fee and the description of the land taken included the fifteen foot buffer strip behind Praught's property. The Order described the third parcel as only being taken for a nonexclusive easement and the description of the third parcel consisted substantially of the way. The Order contained a paragraph following the description of the three parcels which provided that "[t]here is excepted and reserved to those lawfully entitled thereto a right of way over parcel 1 herein taken as and where now located". Although the fee owner of the condemned land was listed on the Order as an owner, received notice of the Taking, and received compensation for the Taking; the individual who held the benefit of the easement at the time of the Taking was not listed on the Order as an owner, did not receive notice, and did not receive any compensation for the Taking. That individual, Praught's predecessor, did not bring either an action for compensation or an action challenging the validity of the Taking. Praught acquired his interest in the property more than two years after the Taking.

These facts raise the following issues:

1 - Does Praught have standing to challenge the validity of the Taking?;

2 - Did the MDC make a valid taking of the fifteen foot buffer strip, in fee, and not burdened by the easement?; and if the answer to the foregoing question is yes,

3 - Did the taking by the MDC render it totally impossible to use the easement for the purpose for which it was created; thereby extinguishing the entire easement?

Mother Brook's first argument alleges that Praught lacks standing to challenge the validity of the Taking because he did not have any interest in the fifteen foot buffer strip at the time of the taking, he did not acquire an interest in the buffer strip until more than two years after the right to damages for the taking had vested, and that his predecessor did not bring an action for damages or to challenge the validity of the taking within the time for bringing such actions as set forth in G.L. c. 79, §§ 16 & 18. Mother Brook relies on Commonwealth v. Quincy Memorial Co., Inc., 13 Mass. App. Ct. 1047 , 1048, rev. denied, 386 Mass. 1104 (1982) in support of its proposition. In Quincy Memorial, the Appeals Court ruled that there was no standing to challenge the validity of a taking when all procedural requirements of G.L. c. 79 were complied with, no proceeding to challenge the validity of the taking had been brought by the then owner of the property within the prescribed time limit, none of the parties challenging the taking had any interest in the property until after the time for bringing such actions was passed, and the deed conveying said property recited that the conveyance was made subject to said taking. Although the facts of this case are distinguishable from those in the Quincy Memorial case, the holding in Quincy Memorial is still controlling on the issue of standing herein. [Note 4]

The applicable versions of G.L. c. 79, §§ 16 & 18, set out a general two year statute of limitation for bringing either an action for compensation under G.L. c. 79, or an action to challenge the validity of a taking. [Note 5] But see Whitehouse v. Sherborn, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 668 , 674 n.11 (1981) (challenge to the validity of a taking may be entertained after the limitations period has run, where the challenge is of a constitutional nature). There are situations, however, when the time for bringing an action may be extended. When an owner does not receive notice of a taking, his right to a hearing for compensation is not limited by the statute of limitation. United States v. 125.2 Acres of Land, 732 F.2d 239, 241-43 (1st Cir. 1984). See also Walker v. Hutchinson, 352 U.S. 112, 115 (1956) (due process requires that owner whose property is taken be given hearing to determine just compensation, and right to hearing is meaningless without notice) But see G.L. c. 79, § 7C (failure to give notice under this section does not affect the time for bringing a petition for damages, except as provided for in § 16); Grove Hall Savings Bank v. Dedham, 284 Mass. 92 , 94-95 (1933) (lack of notice to individual whose land was taken did not extend time to bring action for compensation or invalidate taking).

Despite the fact that a lack of notice may extend the time within which to bring an action for compensation under G.L. c. 79, a lack of notice will not invalidate a taking. 125.2 Acres of Land, 732 F.2d at 241-43; Grove Hall Savings Bank, 284 Mass. at 94-95. See also G.L. c. 79, §§ 16 & 18 (statute allows an additional six month limitation period when notice of taking is not given as required by § 7C, commencing from time actual notice is received or possession of property is taken, whichever occurs first). Praught's predecessor did not bring either an action for compensation or an action to challenge the validity of the Taking within two years from the time his right to compensation vested, nor did he bring either type of action within six months of the time that the MDC took possession of the property. [Note 6] Therefore, not even Praught's predecessor could successfully challenge the validity of the Taking in this case, based on lack of notice, in an action brought over two years after his right to compensation had vested. [Note 7] In the conveyance whereby Praught acquired his property, Praught could not have received any greater rights than his predecessor held. Therefore, Praught, like his predecessor, can not now challenge the validity of the Taking based on a lack of notice to his predecessor. See Markiewicus v. Methuen, 300 Mass. 560 , 564 (1938) (successor in interest to land taken from predecessor by eminent domain could not bring an action for damages where predecessor could not).

Moreover, when Praught purchased his property, a prudent and extensive title search would have revealed the Taking. The fact that the Order was recorded under the servient estate's chain of title does not fatally detract from the level of notice given. [Note 8] See Walpole v. Mass. Chem. Co., 192 Mass. 66 , 70 (1906) (when land taken was burdened by an easement and order of taking was recorded only under servient estate's chain of title, without notifying beneficial owner of easement, recording was held sufficient to vest good title in condemnor). Praught had constructive notice of the Taking when he acquired his property, and therefore, should not now be able to complain of the effect of the Taking. [Note 9]

Based on all of the foregoing, I rule that Praught lacks standing to challenge the validity of the Taking.

Because Praught lacks standing to challenge the validity of the Taking, I shall now proceed to a consideration of the other issues herein on the premise that the Taking was valid in all respects. See Quincy Memorial Co., Inc., 13 Mass. App. Ct. at 1048 (when individual lacks standing to challenge the validity of a taking, court must assume taking is valid). Despite the fact that I am assuming the validity of the Taking, I still must construe the Order to determine what interests were taken in the various parcels included within the Order.

The interest taken in Parcel one of the Order was taken "in fee for open space, recreation, and flood control purposes . . ." The above referenced language clearly sets out the MDC's intent to take Parcel one in fee; and the description of Parcel one includes the fifteen foot buffer strip behind Praught's property. In general, a taking in fee will vest the condemnor with complete title. See Walpole v. Mass Chem. Co., 192 Mass. 66 , 70 (1906); Ace Finance & Investment Co. v. Boston Redevelopment Authority, 51 Mass. App. Dec. 41 (1973). Praught argues, however, that the paragraph following the description of Parcel three which reserves certain easement rights, actually applies to Parcel one. Praught's argument is based on the fact that the designation for the parcel in which the rights were reserved was "parcel 1".

If that paragraph is taken out of context, it clearly refers to the first parcel described in the Order. However, when the language and structure of the entire Order are examined in conjunction with the Plan which is incorporated by reference into the Order, it is clear that the ·reference to "parcel 1" actually refers to the third parcel.

The ambiguity is created by the various designations used in the Order and the Plan to refer to the three parcels taken; namely, Parcels one, two and three; and, Parcels I, II and 1. The Plan uses the designations I, II and 1 to demark the various parcel to be taken. These designations may be seen in the Plan on a table wherein it is indicated that Parcel one is designated I, Parcel two is designated II, and Parcel three is designated 1. Moreover, if the written descriptions in the Order are compared to the three Parcels shown on the Plan, it is clear that Parcel one is designated I, Parcel two is designated II, and Parcel three is designated 1. Further, in the table following the description of Parcel three in the Order, the designation used to refer to Parcel three is "1". The paragraph in issue directly follows that table and also refers to "parcel 1".

If the structure of the Order is also examined, it appeas that the paragraph in issue only applies to Parcel three. The paragraph at issue directly follows the description of the third Parcel taken. The description of the first Parcel and the rights taken therein is completed prior to the descriptions of the second and third parcels and the rights taken therein. Therefore, the logical flow of the paragraphs indicates that the paragraph in issue only applies to Parcel three.

I therefore rule that the paragraph at issue which reserves certain easement rights only applies to Parcel three; and that Parcel one, which includes the fifteen foot buffer strip, was taken in fee unburdened by the easement in dispute.

As a result of the Taking, that portion of the easement which extended over the buffer strip was extinguished. The final issue then is whether the elimination of that portion of the easement extinguished the entire easement. For, the reasons stated hereinafter, I rule that it was completely extinguished.

When the purpose for which an easement was created is rendered permanently or totally impossible of enjoyment, then the easement is extinguished. See First National Bank of Boston v. Konner, 373 Mass. 463 , 468 (1977); Makepeace Bros., Inc. v. Barnstable, 292 Mass. 518 , 525 (1935); Central Wharf v. India Wharf, 123 Mass. 567 , 570 (1878). This doctrine has been held applicable where, in situations such as the one at issue herein, an easement had been obstructed by a taking. Cornell-Andrews Smelting Co. v. Boston and Prov. R.R., 202 Mass. 585 , 596-97 (1909); Hancock & others v. Wentworth, 46 Mass. 446 , 451 (1843).

The easement at issue has clearly been obstructed by the Taking. In order to determine whether the entire easement has been extinguished, a determination must first be made as to what the original purpose for the grant of the easement was, and then a determination must be made as to whether that purpose has been impossibly frustrated.

Praught's property has frontage on Milton Street and also has access to the rear of the property over a second driveway. That second driveway, however, is set on a sixty degree slope. The easement was created to "pass and repass for all purposes" from the rear of the property, extending over certain land now owned by both the MDC and Mother Brook, to Milton Street.

When an easement is granted "to pass and repass" from an individual's property to a public or private way, the obvious purpose in granting the easement, absent any other factors, is to give access from the named property to the named way. The purpose is not to grant access to some other area, nor is it to grant a meaningless cul de sac. Comeau v. Manzelli, 344 Mass. 375 , 381 (1962) (where easement was granted to pass and repass from grantee's property to public way, court was plainly correct in finding that sole purpose of easement was to provide access to public way). I therefore rule that the sole purpose for the easement was to give access to the rear of Praught's property from Milton Street.

The easement was originally granted as an appurtenant right to Praught's property for the purpose of giving access from Milton Street to the rear of the property. Praught no longer has, as an appurtenant right, the right to pass between those two points. The original purpose behind the grant of the easement was, therefore, completely frustrated by the Taking. As soon as Praught's appurtenant right was eliminated in part by the Taking, his entire easement was extinguished. See Cornell-Andrews Smelting Co., 202 Mass. at 596-97 (where access easement was bisected by a taking to create a public way, that easement was extinguished). I therefore rule that the entire easement was extinguished by the Taking, and that Praught no longer has any right to use the way.

Mother Brook has also requested that Praught be enjoined from entering upon or passing over its property. In view of my prior rulings in this Decision, Praught has no right to enter upon or pass over Mother Brook's property, and therefore, Mother Brook is entitled to its requested relief.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The basis for Mother Brooks requested relief is that the MDC took by eminent domain a portion of the servient estate for Praught's easement. Praught's answer alleged that the MDC did not have good title to that land, and therefore, the MDC was a necessary party to the suit.

[Note 2] Appendix A, is a reduced copy of a plan, which was an exhibit in the case, entitled "Mother Brook-Dedham, Land Taking Plan For Open Space, Recreation & Flood Control", dated February 26, 1975 (the Plan). Certain labels have been added to the Plan to aid in locating various relevant areas. The Plan was incorporated by reference into the Order of Taking at issue herein.

[Note 3] All documents listed herein are recorded at the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds, unless otherwise noted.

[Note 4] In this case, Praught's predecessor never received notice of the taking, while in Quincy Memorial, both the owner at the time of the taking and the subsequent owner both had notice of the taking. Praught, however, did receive constructive notice of the taking by way of the recorded Order, prior to acquiring his interest in the abutting property.

[Note 5] General Laws c. 79, §§ 16 & 18 now provide for a general three year statute of limitations. This version of the statute, however, does not apply to Praught or his predecessor because the relevant amendment to the statute was not enacted until 1982.

Under § 16, if notice of the taking is not received within sixty days of the expiration of the limitation period, then the owner of the property has six months to bring an action, from the time possession is taken of the property or actual notice of the taking is received, whichever occurs first. See Cann v. Commonwealth, 353 Mass. 71 (1967) (actual notice refers to knowledge of the taking, and not notice of the right to compensation as provided for elsewhere in c. 79).

[Note 6] Although Praught's predecessor did not receive notice of the Taking, as required by § 7C, the MDC took possession of the property in the 1970's, and no action was brought for compensation or to challenge the validity of the Taking within six months of that period.

[Note 7] Praught also argued that the fact that the MDC failed to compensate his predecessor and failed to assess damages for the Taking, as required by G.L. c. 79, § 6, somehow invalidates the Taking. A failure to assess damages, as required by G L. c. 79, § 6, however, will not invalidate a taking. Broderick v. Dept. of Mental Diseases, 263 Mass. 124 , 128 (1928).

[Note 8] Generally, constructive notice would not be sufficient to notify an owner of land that his land had been taken and of his right to compensation for the taking. In this case, however, Praught was not the owner at the time of the Taking, and therefore, is not entitled to the same level of notice as such an individual.

[Note 9] It is questionable what right a subsequent owner of condemned property has to challenge the validity of a taking in view of the principal that the right to compensation for a taking vests in whoever owns the condemned property at the time of the taking, and that right does not normally pass in a subsequent conveyance by that owner. See Howland v. Greenfield, 231 Mass. 147 , 148 (1918) (well established that only owner at time of taking has any right to damage, and such right does not pass in a subsequent conveyance by owner); see also Skahan v. Commonwealth, 299 Mass. 25 , 25-28 (1937) (where testator died prior to commonwealth taking subject property, as between executor of testator's estate and the named beneficiary for the subject property under the will, the right to damages was vested in the executor).