The plaintiff Cummings Property Management, Inc. ("Cummings") proposed to provide through a third party, a helicopter service to and from Logan Airport to tenants of its Woburn office park as well as to the public-at-large, from the property which is located at the interchange of Route 128 and Interstate 93. The Woburn City Council (the "Council"), sitting as special permit granting authority, twice denied the Cummings' application for a special permit, and Cummings appeals pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 40A, §17, and seeks declaratory relief pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §14A to the effect that the bylaw requiring a special permit is preempted by G.L. c. 90, §35-52, inclusive, establishing the Massachusetts Aeronautics Commission and governing the regulation and operation of aircraft in the Commonwealth.

The matter initially reached this Court with both the present plaintiff and the air carrier, HubExpress Airlines, Inc. ("HubExpress"), of Stow, Massachusetts, as named plaintiffs. Pursuant to a stipulation filed March 7, 1989, the latter's claims against the defendants were dismissed with prejudice. Following a pre-trial conference, the two remaining parties agreed to the entry on June 28, 1989 of an Order of Remand (Fenton, J.) returning the matter to the City Council for reconsideration of its decision and for a new hearing. Following that subsequent hearing the Council again denied the application for special permit citing grounds other than those originally relied upon. Cummings did not amend its complaint to include the Council's decision after remand.

A trial was held in the Land Court on September 10, 1990, at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. In all, 19 exhibits were admitted in evidence which are incorporated herein in the event of an appeal. Five witnesses testified on behalf of Cummings: William Gustus, Esq., General Counsel to the plaintiff; James McKeown, President of plaintiff corporation; Rhett Flater, President of HubExpress Airlines; Michael Dever, former chairman of the Woburn City council; and John

N. Cashell, Coordinator for the Woburn Planning Board. The Council called no witnesses.

At the close of the evidence Cummings filed a motion for summary judgment and brief in support thereof. Because material issues of fact remain, the motion hereby is denied. Moreover, the purpose of a summary judgment is to alleviate the burden on a Trial Court by rendering a trial unnecessary. It has no role after the case has been tried. In addition, Count IV of the complaint was dismissed by agreement of the parties.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

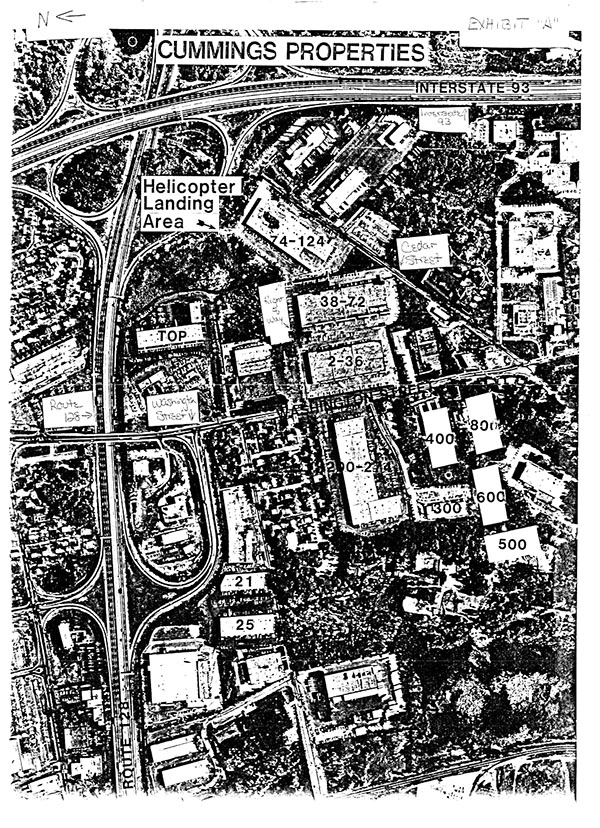

1. Cummings owns and manages a sizeable office park in the City of Woburn, consisting of about 3,000,000 square feet of space, accommodating nearly eight hundred tenants, employing 10,000 to 12,000 workers, located within the Office Park zoning district which permits office parks of right and helicopter landing areas by special permit. Washington Street, a busy thoroughfare providing access to and from Route 128, bisects the developed land; the helicopter landing area (also "site" or "helipad" or "heliport") is easterly of Washington Street and at the far easterly end of the office park adjacent to Routes 128 and Interstate 93. See Exhibit "A" (marked Chalk A at trial) to which the Court has added further landmarks, showing the helipad situated northwesterly from building 74-124. The site is within 100 feet of a wetland, but the filing of a notice of intent with the Woburn Conservation Commission pursuant to G.L.c. 131, §40 awaits a final decision in this appeal.

2. Washington Street, on which the plaintiff's office park has frontage on the southwesterly side of this "parcel" or "locus" [Note 1], was a busy two lane roadway at the time the special permit was denied; plans were approved for its expansion to four lanes of which the City Council was aware and had at the time of trial in fact been expanded to four lanes in the area of locus. Access to the proposed helipad is over a right of way running easterly and norteasterly from Washington Street to the rear of the parcel, as well as by a second entrance which opens into the common parking area surrounding the three buildings on locus. Access also may be obtained from Cedar Street, which forms the southeasterly boundary of locus and dead ends at what was then and may still be a trucking terminal, through a fence which is open during operating hours. [Note 2] Pedestrians will gain access to the helipad by walking through the parking lot and depending on their point of origin may have to cross Washington Street. It is not intended that any part of the parking lot will be designated for customers of HubExpress, and parking will be in common with all tenants. Availability is not guaranteed; a sizeable parking lot is adjacent to the helipad, with overnight parking designated "snow parking" on neighboring land of Cummings.

3. Cummings entered into a license agreement with HubExpress, which was approved by the Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration ("FAA"), whereby HubExpress would provide a commercial helicopter shuttle service between the site [Note 3] and Logan International Airport in exchange for use of the landing site. Cummings does not stand to profit directly from the venture, and it will receive no rental payments from HubExpress. The service is available to the plaintiff's tenants, a fringe benefit, as it were, and the public-at-large although the service is not advertised beyond the office park. [Note 4] During the months of June, July and early August, 1988, HubExpress offered service on an on-demand basis. Records (not in evidence) kept by HubExpress in taking reservations show that forty-eight passengers, all connected with the office park in some capacity, flew on 30 flights over the roughly two and one-half month period. Service was discontinued following the City Council's first denial of the special permit which prompted the original appeal. Once normal operations commence, if they do, flights will operate on a scheduled hourly basis beginning at approximately 6:30 A.M. with the last departure from Logan no later than 8:30 P.M., and with flights also at 12:00 noon and 1:00 P.M.

4. The airline has a total of four helicopters, two in service, two for back-up. The sizes vary between the Bell Jet Ranger, seating four passengers, and the Bell Long Ranger, seating six passengers; each is considered "modest in size". In addition, the airline is fully "certificated" by the Department of Transportation and the FAA. The HubExpress service referred to above operated from the Cummings Park site after it had obtained a limited commercial use private landing area approval from the Massachusetts Aeronautics Commission ("MAC"). In addition to these approvals, HubExpress also obtained its international three-letter identifier from the International Air Transport Association in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, which assigns to landing areas and airports the familiar three letter identification; the Cummings Park/Woburn identifier is "WBN".

5. The helipad is visible on the ground; 70 feet by 70 feet for a total area of 4,900 square feet, comprised of four telephone poles forming a square with red lights atop each as well as red lights at halfway points between each pole all according to FAA guidelines regarding visual flight rules ("VFR") heliports (of which the proposed site is one); a barrier is in place, as required, to keep out vehicles, pedestrians and the like from unwittingly straying onto the helipad, and a windsock is affixed to the corner of building 74-124 as a wind direction indicator. No other peripheral lighting fixtures are required or installed.

6. "Helicopter, rotary-wing aircraft, or gyroplane landing area" is permissible as a principal use in the Office Park zoning district only by special permit. See Exhibit No. 1, Use #52. On May 8, 1988 HubExpress applied for a special permit to conduct the service between Cummings Park and Logan Airport, which operation does not include refueling, storage or maintenance. The FAA distinguishes, as does the MAC, between public and private landing areas; the City of Woburn does not. A private landing area is

limited to a particular carrier or by permission of the owner, as opposed to a public facility which permits all aircraft to land generally day or night. Accordingly, what plaintiff proposes is a private landing area as defined by the FAA. Finally, HubExpress does not have ambulances among its fleet, but it has offered emergency assistance to local officials. The Woburn Planning Board, as well as the Police and Fire Chiefs, forwarded favorable recommendations of the proposal to the City Council citing various reasons including accessibility to Medi-Vac and other emergency services, notwithstanding some concern about take-offs and landings over residential areas. The nearest residential areas are across Washington Street westerly of locus (estimated to be a distance of seven hundred feet from the helipad), and southerly from locus a greater distance away. A closer residential neighborhood is separated from the site by eight lanes of Route 128 to which it is adjacent. There was some testimony at trial suggesting this position may have been subsequently changed, but no evidence to that effect was offered or pursued.

7. Mr. Fralick of the Board of Health conducted a noise emission study in connection with a determination as to whether the location of the helipad posed a health risk to area residents. Permissible noise levels were dictated by a then newly enacted noise ordinance. The nearest points of the two residential areas nearest the site were tested, westerly and southerly from locus as described above, as well as various points around the office park. Noise levels were measured for take offs, approaches and landings both within and without designated flyways. Because of ambient background noise from the adjacent highways and Washington Street the helicopter use did not register. Also, it appears from the Planning Board report that the Board conducted its own noise emissions testing and found the use proposed no detrimental effect to the health and welfare of area residents.

8. The Massachusetts Aeronautics Commission granted approval on March 16, 1988 for a private landing area subject only to agreement with the FAA and compliance with other rules not here in issue. Typically, application is made to the MAC only after the site has been inspected in terms of openness to ensure take-offs and landings will not be over residential properties as well as to ensure proximity to FAA approved flyways. The MAC will then conduct its own inspection of the site to approve its overall safety, noise abatement and the appropriateness of the site.

9. The FAA approved flyways to be used by HubExpress are referred to by the FAA and shown on local charts as the Hampshire Route. This route runs east/west, parallel to Route 128, turning north/south at the interchange with Interstate 93 (adjacent to the heliport) and running parallel to that highway; aircraft fly at an altitude between 1,000 feet and 2,500 feet depending on the cloud ceiling. The route is currently in use by HubExpress to shuttle passengers between New England Executive Park in Burlington and Logan Airport; any stopover at the Cummings Park helipad would nominally deviate from their existing flight plans. Approaches to the Cummings Park site depend largely on wind direction but, according to Mr. Flater, would be either a direct approach from a westerly direction or an approach involving circling over the 128/93 interchange with the helicopter heading easterly as it lands.

10. On August 16, 1989 the Woburn City Council as special permit granting authority denied the special permit citing as grounds therefor:

1. The location is not suitable for this use.

2. The petitioner has conducted business at the location without a permit, which shows bad faith.

3. The petitioner has not shown it does in fact operate within prescribed flyways and does not have a good track record.

4. The flyways over the busiest intersection in the state is an attractive nuisance.

11. By Order of this Court (Fenton, J.) the matter was remanded for reconsideration as to whether the application for special permit met requirements of §11 of the 1985 ordinance, as amended (Exhibit No. 10). The 1990 edition of the Woburn Zoning Ordinance was marked Exhibit No. 1; accordingly, and assuming the relevant provisions of §11 were the same for each decision, the City Council as special permit granting authority to grant a special permit must find:

1. Satisfactory provision and arrangement of ingress and egress to property and proposed structures thereon with particular reference to automotive and pedestrian safety and convenience, traffic flow and control and access in case of fire or catastrophe. If traffic due to the proposed use is projected to exceed the capacity of existing roadways, a service road or divided entrance may be required by the City Council.

2. Adequacy of the capacity of water, sewerage and drainage facilities to service the proposed use.

3. Adequate offstreet parking and loading areas where required with particular attention to the items in Section 11.5.1 and the noise, glare, or odor effects [sic] of the proposed use on adjoining properties and properties generally in the district.

4. Satisfactory provision of refuse collection, disposal and service areas, with particular reference to impacts on adjacent uses.

5. Exterior lighting with reference to glare, traffic safety, and compatibility and harmony with properties in the district.

6. Yards and other open space and landscaping are provided as required and reasonable steps have been taken to insure the privacy of adjacent existing uses.

7. The proposed use is in general "compatibility in scale and character with adjacent properties and other property in the district.

8. The proposed use or structure will not be adverse to the general purposes of this ordinance.

9. The Council shall also impose such additional conditions of those specified in this Ordinance as it finds reasonably appropriate to safeguard the neighborhood or otherwise serve the purposes of this Ordinance, including but not limited to the following: . . . screening, buffers, or plantings strip, fences or walls, as specified by the Council modification of the exterior appearance of the structure; . . . method and time of operation, or extent of facilities; regulation of number and location of drives, accessways, or other traffic features, and off-street parking or loading, or other special features beyond the minimum required in the ordinance.

12. Upon remand a new hearing was scheduled and advertised with Cummings expressly advised that no new evidence would be considered. What appears to have been offered as minutes of that hearing were marked Exhibit No. 19 at trial showing the Council vote again denying the special permit, and reciting verbatim §§11.5.1, .3, and .8; paragraph 4 of the exhibit was not properly

photocopied. It contains no substantive provision and ends "this will increase traffic in area and therefore, would be detrimental" without any explanation as to what this conclusion relates. This is the only statement indicating any sort of "Finding" made by the Council. The City Council's decision, Exhibit No. 13, cited as reasons for denying the special permit on remand:

1. As required by the provisions of Section 11.5.1 of the [Ordinance], the City Council finds that satisfactory provisions for vehicular and foot traffic to and from the proposed locus has not been made in that a) the proposed use will necessarily increase vehicular and foot traffic in the locus, b) the locus is already, to the City Council's knowledge, oversaturated with vehicular traffic to a dangerous degree, and c) the Co-Applicants presented no proposals to alleviate USE saturation in the locus.

2. As required by the provisions of Section 11.5.8 of the ORDINANCE, the City Council finds that the proposed use will, in fact, be adverse to the general/purposes [sic] of the zoning ordinances as those purposes are more specifically outlined and described in Section 1.1.1, in that an increase in traffic will necessarily occur on Washington Street, on which vehicular traffic is already seriously congested; and, further, in accordance with Section 1.1.3., the City Council finds that the proposed use creates a danger to the public in that the flight path of the Helicopter includes areas of the City of Woburn devoted entirely to residential use.

Cummings' appeal raises several key issues, including the extent to which a municipality may regulate land within its borders without conflicting with areas already preempted by state and federal regulators; the validity of the rejection by a municipality of a use proposed as accessory to a separate permitted principal use when the city or town legislative body has already classified the use as a principal use; and finally a consideration of whether the SPGA's decision was in accordance with law or arbitrary, whimsical, capricious, unreasonable or based on legally untenable grounds.

Preemption /Accessory Use

Cummings claims that provision of the zoning ordinance making the proposed use of a heliport subject to a special permit is preempted by state and federal law. Chief among its arguments is that G.L. c. 90, §§35 to 52, in part empowering the Massachusetts Aeronautics Commission to set forth statewide plans for the siting of aircraft landing facilities, erects a barrier to local interference with the MAC's legislatively mandated function of devising an overall plan for the operation of aviation facilities within the Commonwealth. Accordingly, so goes plaintiff's argument, any local ordinance or bylaw directing the location of such a facility is prohibited as state law has occupied the field and its purpose would be frustrated by operation of the local law. I do not, however, reach the question as to whether the Commonwealth has preempted the field. Rather I hold that the maintenance of a helipad on the Office Park locus is accessory to the principal use of the premises. I further find and rule that if in fact the Woburn Zoning ordinance requires a special permit for the proposed private landing area, then the City Council acted arbitrarily and unreasonably and not in accordance with law in denying the grant.

The Woburn Zoning ordinance formerly recognized a helicopter landing area as a permitted use in an office park district, but it now requires a special permit for a "helicopter, rotary-wing aircraft or gyroplane landing area". The plaintiff has contended, but does not now push its argument, that the approval of the subdivision plan of the area preserved the previous zoning, but I do not have before me the plan in question and the relevant dates so I am unable to address this question intelligently. The operation of the helicopter land area in contention here is limited to one company, is in effect to serve only tenants of the plaintiff although open to the public and will draw for patrons on the businesses already in the office park and their customers, all of whom need to be ferried from Wobun to Logan International Airport in East Boston. To a very large extent the HubExpress passengers are people already in the park whose cars would be there in any event or those parties from the Eastern Seaboard cities who have business with tenants of the plaintiff and need transportation to the office park. Whether the helicopters would be a source of more problems than the present MBTA service is certainly not clear.

In Harvard v. Maxant, 360 Mass. 432 (1971) where the defendant sought permission for a private landing strip in a residential area the Supreme Judicial Court delineated the line between principal and accessory uses.

In construing whether a use is "incidental to a principal use [and] customarily found in connection therewith," Justice Quirico

quoted extensively from a decision by Connecticut's highest court in Lawrence v. Zoning Board of Appeals of North Branford, 158 Conn. 509, 512-513 which held that:

The word "incidental" as employed in a definition of "accessory use" incorporates two concepts. It means that the use must not be a primary use . . . but rather one which is subordinate and minor in significance. . . . But "incidental" . . . must also incorporate the concept of reasonable relationship with the primary use. It is not enough that the use be subordinate; it must also be attendant or concomitant.

The word "customary" is even more difficult to apply. . . . Courts have often held that use of the word 'customarily' places the duty on the board or court to determine whether it is usual to maintain the use in question in connection with the primary use of the land (citation omitted). . . [It must be] determine[d] whether [the accessory use] has commonly, habitually and by long practice been established as reasonably associated with the primary use. . . .

In applying the test of custom, we feel that some of the factors which should be taken into consideration are the size of the lot in question, the nature of the primary use, the use made of the adjacent lots by neighbors and the economic structure of the area. As for the actual incidence of similar uses on other properties, geographical differences should be taken into account, and the use should be more than unique or rare, even though it is not necessarily found on a majority of similarly situated properties. . . .

The Harvard court commented that even though travel by air was on the rise it had not become so prevalent in 1971 as to allow a finding that a private landing strip had become customarily incidental to a residential use. The Court, however, limited its decision to the facts. In a similar but factually distinguishable case Justice Elbert Tuttle in a 1985 decision held that a helicopter service was an accessory use to the plaintiffs' principal use as corporate business. There, the service was used occasionally and only for the corporation; two other similar uses were nearby; the nearest residential structure was 1,900 feet away. Data General Corp. v. Zoning Board of Appeals for the Town of Westborough, Worcester Superior Court Civil Action No. 85-30495. The situation before me is very similar to that in Data General since a limited group of passengers will be solicited. The characterization of the service as a private landing area by the MAC is governed by the limitation of the service to one carrier rather than the nature of the service. I find and rule that the proposed operation is accessory to the office park in the same fashion as that of Data General (see also Needham v. Winslow Nurseries. Inc., 330 Mass. 95 , 101 (1953)), and that such use may be made of the site even though it is not listed as an accessory use in the ordinance.

If, however, statutory construction or estoppel from the plaintiff's application for a special permit requires that the plaintiff seek a special permit, I find and rule that it was arbitrary and unreasonable of the City Council not to grant the special permit and that the decision was based on a legally untenable ground. The only explanation for the decision when the proposed service was approved by the Planning Board, the Board of Health, the fire and police chiefs lies in the number of neighborhood votes. The FAA has preempted the field as to a determination of appropriate flyway, and the location of the site at the junction of Routes 128 and 95 is within them. The city Council was without authority to disagree. Moreover, any question of traffic is no longer viable because Washington Street has been widened to better serve the area. In addition, the customer base for the helicopter service vitiates any argument based on an increase in parties entering the office park.

Denial of the Special Permits

The City Council's first denial of the special permit application cited as reasons for denial suitability of location, petitioner's bad faith, petitioner's track record and failure to show the airline "in fact operate[s] within prescribed flyways", and the location of flyways was an "attractive nuisance". Although Justice Fenton of this Court remanded the matter for "rehearing and reconsideration of the denial, the City Council in again denying the special permit amended rather than superseded its original decision. Accordingly each decision must be addressed.

It is well-settled that an applicant has no absolute right to a special permit, which may be denied by the special permit granting authority in its discretion, even if one could have issued. Gulf Oil Corp. v. Board of Appeals of Framingham, 355 Mass. 275 , 277-278 (1969). In the exercise of its discretion, however, it may not act arbitrarily, capriciously, whimsically or unreasonably, nor base its decision on legally untenable ground. MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 638-639 (1970). It is only if these circumstances are found after a trial de novo, that the court may annul the decision of the special permit granting authority. Subaru of New England. Inc. v. Board of Appeals of Canton, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 483 , 486 (1979).

The first decision lists four reasons for denying the location of the helipad which are noted above. I have already considered the question of the flyway which was without the council's power to influence. The other reasons advanced by the Council in its first decision cannot be upheld. The second decision prepared by the City Solicitor for the Council's consideration focused on traffic which I have already discounted.

The first basis, quoted previously, was concerned with an expected increase in vehicular and pedestrian traffic within a lot allegedly already "oversaturated . . . to a dangerous degree" and there was no proposal forthcoming to "alleviate use saturation". As a matter of law these justifications for denying the special permit cannot stand.

First, §11 provides that "[i]f traffic due to the proposed use is projected to exceed the capacity of existing roadways, a service road or divided entrance may be required by the City Council." (emphasis added). There was no evidence at trial that introduction of the helicopter service would have any traffic impact whatsoever. More particularly, there was no evidence that any additional traffic caused thereby would be in excess of the roadway's capacity. At no time during meetings/hearings with the city Council were issues of traffic impacts raised; either for vehicular or pedestrian traffic. In the course of plaintiff's presentation to the City Council, access and parking arrangements were discussed and pointed out to Council members; pedestrian access was not specifically addressed. No formal traffic studies were conducted by plaintiff, nor requested by the City Council. The Council argues that because the plaintiff did not provide them with this information, this justifies their finding that the service would impact negatively on an already overburdened traffic system along Washington Street in violation of one of the special permit criteria. This is plainly in error; all the absence of the traffic study shows is that there was no such study before the Council at the time it rendered its decision. It appears, however, that because Washington Street has since been widened, any traffic congestion from whatever source would not pose the problems feared when the application was originally denied.

Second, the City Council expressly forbade the presentation of any additional evidence and none as to traffic was ever presented in connection with the first denial. Accordingly there exists no evidence from which the Board may conclude that any noticeable increase in traffic, vehicular or pedestrian, will occur. Only tenants of the office park and their employees, presumably already on site (whether they arrived by their own automobile or by public transportation), will be directly solicited by HubExpress. This, together with the fact that overall the office park supports some 10,000 to 12,000 employees daily, requires the common sense conclusion that any increase in traffic will go unnoticed.

I therefore find and rule that the plaintiff was entitled to establish a helipad as an accessory use without Council approval. I further find and rule that if a special permit were required, the Council's denial of the special permit violated the standards. Customarily the Court does not order a special permit to be issued. This matter already has been remanded once, however, and the Council's intransigence remains. If on appeal it is held that the plaintiff is not entitled to operate the helipad as an accessory use, then the question of a special permit may be treated.

The parties have requested certain findings of fact and rulings of law, but I have made my own without ruling specifically on the requests.

I decline to rule under c. 240, §14A on the question of preemption as I have dealt with the appeal under section 17 of Chapter 40A.

Judgment accordingly.

CUMMINGS PROPERTY MANAGEMENT, INC. vs. CITY COUNCIL FOR THE CITY OF WOBURN.

CUMMINGS PROPERTY MANAGEMENT, INC. vs. CITY COUNCIL FOR THE CITY OF WOBURN.