The plaintiffs Mark D. Sullivan and Phyllis W. Keene (referred to herein as "the plaintiffs") brought a complaint pursuant to the provisions of G.L. c. 185, §l (a) to register the title to land on Main Street in Hopkinton in the County of Middlesex on which is situated their restaurant known as the "Morning Star Cafe". In Miscellaneous Case No. 148823 the Town of Hopkinton (the "Town") brought a complaint for a declaratory judgment pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 231A which relates to an obstruction placed by Sullivan and Keene on the land claimed in the registration complaint. The Town objects to the obstruction on the ground that it blocks access to two adjoining parcels of registered land owned in fee by third parties over which the Town through its police chief seeks to have traffic exit from the locus and the town hall lot. The owners of the registered land (formerly the Hopkinton Savings Bank, now the Bank for Savings and the Hopkinton Acacia Club, Inc.) are not parties to this complaint [Note 1] nor is the registered land subject to any rights of way of record therein. The registration complaint now before the Court was brought because the title examination at the time of the purchase by the plaintiffs revealed that there was no record title to a major portion of the rear of the premises, but other issues have been presented during the course of this litigation. The first concerns the right, if any, as appurtenant to the locus, to pass and repass on foot and in vehicles, over land of the Town of Hopkinton on which the Town Hall is located between the latter building and the plaintiffs' building to reach the rear of the plaintiffs' premises. The second question concerns a) the nature of the right of others to park behind the cafe including members of the public as well as municipal employees and customers of Sullivan, b) of the Town's right to direct the direction of the traffic in the right of way and across the plaintiffs' land to that of the bank and club and c) of the plaintiffs to block access from their land to the exit favored by the Town.

The two actions were tried together on July 8 and September 26, 1991 at which a stenographer was appointed to record and transcribe the testimony. All exhibits introduced into evidence are incorporated herein for the purpose of any appeal. The plaintiffs called as their witnesses Margaret Wittenberg, the Land Court examiner who prepared the abstract of title, William Smith, a former owner of the locus (the deposition of his partner Thomas Brown, who was unable to testify because of visual impairment, being introduced into evidence as Exhibit No. 18), Glen Cameron, a prior owner of the premises and the plaintiff Mark Sullivan. The defendant called Robert Kumlin, the foreman of the Hopkinton Highway Department, Patricia Ann Lambert, a registered land title examiner, William McRobert, the Hopkinton police chief, Robert Bartlett, the highway superintendent and water foreman for the Town of Hopkinton, Robert McMillan, the fire chief and Arthur Stewart, retired fire chief. A view was taken by the Court in the presence of counsel on February 12, 1992.

On all the evidence I find and rule as follows:

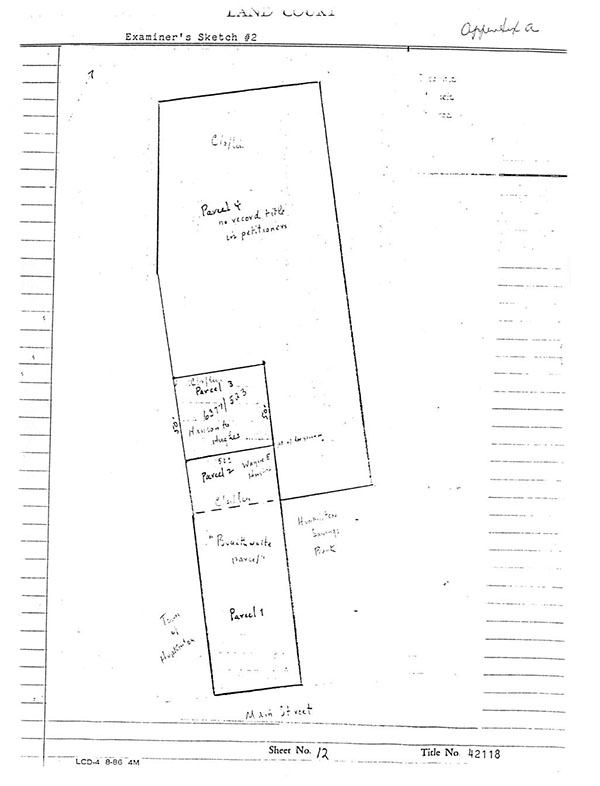

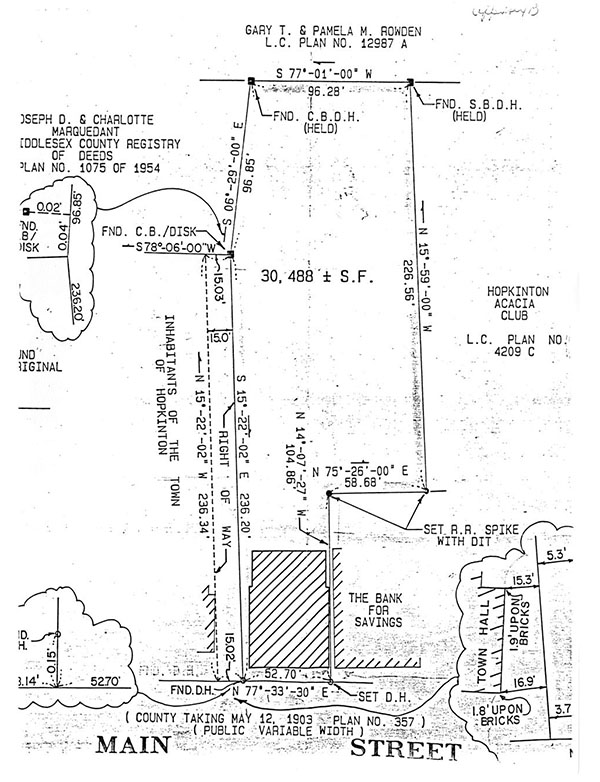

1. The locus consists of four parcels of land which are shown on a sketch by the examiner which appears at page 12 of the abstract which is Exhibit No. 1. A copy of this sketch is attached hereto as Appendix A and of the pertinent portion of the filed plan as Appendix B. It is Parcel 4, as shown on the Examiner's sketch, to which the plaintiffs have no record title. The other parties to this litigation do not dispute that the plaintiffs have acquired title thereto by adverse possession, and so far as they are concerned this acquisition has been assumed. After a consideration of the record the Court now rules that publication may serve as notice to, and it will not require, a further effort to locate the missing record owners, their heirs or assigns. The 1and as to which the plaintiff clearly has title comprises about 52.70 feet on Main Street and is approximately 193 feet in depth.

2. The plaintiffs acquired their title from Glen A. Cameron and Barbara Earle by deed dated October 8, 1986 and recorded with Middlesex South District Deeds in Book 17476, Page 354 (to which registry all recording references herein refer). For the first time in the chain of title the present locus is described in the deed to the plaintiffs as including all four parcels and as being the lot containing an area of 30,461 square feet as shown on a plan entitled "Plan of Land in Hopkinton, Mass. Property of Thomas J. Brown and William J. Smith" dated September 2, 1965 by Schofield Brothers recorded as Plan No. 85 of 1981 in Book 14200, Page 355 (Exhibit No. 8). If the Schofield plan had been recorded earlier, it would have made the claims of the plaintiffs apparent on the record at a much earlier time.

3. Previous to the most recent description of the premises each parcel, as acquired, had been described separately.

4. The plaintiffs' chain of title commences with a deed from William Claflin et al to James W. Braithwaite dated April 23, 1888 and recorded in Book 1846, Page 576 conveying a parcel of land on Main Street with a frontage there of 52 1/6 feet but without specific distances given as to the other boundaries. There is a second record of this deed in Book 1882, Page 82. The second parcel comprising the locus was acquired by Samuel Crooks et al from Daniel T. Bridges et al by deed dated December 19, 1888 and recorded in Book 1888, Page 291. Both the deed to Braithwaite and the latter deed conveyed such rights as the grantor had over the easterly side of the land of the Town of Hopkinton. Subsequently Charles L. Claflin acquired Parcels 2, 3 and 4 by deed dated May 3, 1900 and recorded in Book 2816, Page 45 which included the grant of the right of way. Thereafter what the examiner has denominated Parcel 2 was conveyed by Edward W. Pierce et al, trustees under the will of Charles L. Claflin to James W. Braithwaite by deed dated February 1, 1906 and recorded in Book 3215, Page 199. The remaining Parcels 3 and 4 were acquired by Frank A. Hanson from the surviving Pierce trustee by deed dated August 6, 1924 and recorded in Book 4826, Page 201. A long narrow strip north of the land conveyed to Hanson subsequently was registered, and blocks access to the north and any public way beyond it. Subsequently Mr. Hanson conveyed his two parcels to M. Eleanor Hanson and Alice A. Hanson

by deed dated September 28, 1939 and recorded in Book 6335, Page 284, and the latter grantees conveyed Parcel 3 only which was a 50 foot parcel to Wayne E. Hughes by deed dated March 15, 1940 and recorded in Book 6377, Page 523. This left the remaining Parcel 4 in M. Eleanor Hanson et al, and record title remains there today.

5. Mr. Braithwaite acquired his two parcels separately, and they continued to be so described in subsequent conveyances by those claiming under him. Wayne E. Hughes acquired Parcels 1 and 2 by a deed dated September 7, 1938 and recorded in Book 6235, Page 346 with the parcels so described, and he subsequently acquired Parcel 3 as set forth above from M. Eleanor Hanson et al; he then conveyed all three parcels to himself and his wife as joint tenants by deed dated March 29, 1946 and recorded in Book 6956, Page 254, again describing each parcel separately. The Hughes followed the same pattern when they conveyed the property to James J. Brown and William J. Smith by deed dated May 9, 1946 and recorded in Book 6971, Page 113.

6. Messrs. Smith and Brown followed the same pattern in conveying to Glen A. Cameron and Barbara Earle by deed dated January 24, 1981 and recorded in Book 14200, Page 355 in which the three parcels were separately described and no conveyance was made of Parcel 4. Although this deed did reference the Schofield plan of the entire locus, it was not until the present plaintiffs acquired title that the property was described as a unified whole which would be of assistance in establishing the doctrine of color of title. See Norton v. West, 8 Mass. App. Ct. 348 , 350-351 (1979).

7. In all of the conveyances in the plaintiffs' chain there is a specific reference to the conveyance being with the benefit of and subject to all rights of way. This is of particular importance in the present litigation since there is a question as to whether predecessors in title released to the Town all rights of way across the Town land. The ambiguity arises from a deed given by William Claflin et al to the Inhabitants of the Town of Hopkinton dated August 12, 1882 and recorded in Book 1610, Page 359 in which this wording appears, all without punctuation, after the conclusion of the description of the granted premises. "Also all the right to pass and repass or easements that we now have in the land now owned by the town contained in a deed from E. A. Bates to William Claflin and N. P. Coburn the above premises are conveyed subject to any rights of easements that the town has in the above described premises."

8. In a deed from Bates to Claflin and Coburn in 1849 there were both a 12 foot wide right of way to the westerly side of the premises and an 8 foot wide right of way on the easterly side.

9. At least from the conveyance out to Braithwaite in 1888 to the present the owners of the locus (and many others) have used the driveway between the properties of the Town and the plaintiffs for access to and egress from the vacant land behind the building on the locus. So far as appears, the Town has never objected to such use and recently has recognized it by contributing to the cost of paving. There is a roof drain from the plaintiffs' building which now empties into the municipal system in the way; the

plaintiffs initially paid the expense of repaving the way, and the Town reimbursed them for its share. The language of the release is troublesome, but I find and rule that this applied to the 12 foot wide right of way to the west of the building then on the Town Hall property and not to the way on which our attention has been focused.

10. There was testimony that as early as the mid-1960's the traffic from Main Street entered the driveway, proceeded in a northerly direction to the vacant land in the rear where the cars were parked and then left the site through a parcel of registered land belonging to the nonparty bank and Acacia Club. At some point there was painted on the right of way "one way only" and from time to time the Town has erected signs to this effect on its property. There presently is a "Stop" sign in the rear of the Town Hall facing the parking lot to deter traffic from exiting over the way. Despite the Town's efforts, however, traffic frequently proceeded in a two way fashion on the right of way. Town officials, specifically the police and fire chiefs and the highway superintendent, are of the opinion that the one-way traffic pattern is safer than one which utilizes the right of way in question for two way traffic since the buildings on the Town and the plaintiffs' lot are close to the street line and the line of sight is poor whereas these failures do not affect the Bank's property. The way also is narrow for cars to proceed in each direction, and there is an entrance into it from the Town Hall.

11. Apparently Mr. Smith annually used to block the right of way. To the extent that at least fifteen feet of it is situated on land of the Town, this action was without authority and was the result of some misguided advice given to him without regard to the fee ownership of the land over which the easement passes. The present plan shows a 15 foot wide right of way all situated on land of the Town. The way is about 3.7 feet from the southwesterly corner of plaintiffs' building and 5.3 feet from its northwesterly corner, but on the ground it is paved to the building and the delineation is unclear or nonexistent. At the most the plaintiffs' rights would seem to encompass eight feet only of the fifteen foot right of way on the Town's property. The westerly seven feet of the right of way is an area not encompassed by the plaintiffs' record right, but they are entitled to use it as members of the public. As a practical matter everyone uses the entire space between the two buildings which has a macadam surface.

12. Owner's Duplicate Certificate of Title No. 53661 gives as the registered owner of Lot A on Land Court Subdivision Plan No. 4209B, Hopkinton Savings Bank; the Court understands that its successor is the Bank for Savings and the certificate should be updated. The certificate covers a parcel of land known as Lot A, approximately 10 feet by 107 feet, and it is subject to no rights therein (Exhibit No. 16B). Adjoining Lot A is Lot B on said subdivision plan, the record owner of which is Hopkinton Acacia Club, Inc. Lot A and the adjoining space between it and the Club building is approximately twenty-five feet wide. Lot A and the Club's property are shown on said subdivision plan (Exhibit No. 16C), and it is clear that to reach this registered land from the locus it is necessary not only to cross the locus but also to cross other land of the bank or the land shown as Lot B on the plan said to belong to the Acacia Club. In any event there is no record right to cross either Lot A or Lot B, and no right can be acquired by prescription since Chapter 185, §53 specifically proscribes the acquisition by prescription of rights in registered land. Accordingly the town officials are without authority to require on private property that cars exit through said land of third parties or indeed to cross land of the plaintiffs to reach the former. Since the Town is the fee owner of the right of way, it can control the passage of others through it if there were any other exit which it could guarantee to those that enter from Main Street. This it cannot do without the agreement of the plaintiffs, the Bank and the Club. The Town, however, is not powerless since it may take by eminent domain a right of way across the plaintiffs' land and through the Bank's and Club's parcels to reach Main Street. The board of selectmen is the proper party, of course, to make this determination; in the alternative the board may wish to secure instead an easement from the parties over whose land the way would go. I have not reached the question as to whether the Town can impose one-way regulations on a right of way which the plaintiffs have a record right to use, since at present it is impossible to impose such a regulation. Clearly the Town could do so by eminent domain. Until, however, there is a clear right to exit elsewhere, the Town cannot enforce the one-way rule.

13. The owners of the plaintiffs' land, at least since Brown and Smith, have used the land in the rear of what is now the cafe and in the past has been a variety and a newspaper store for their own purposes. Trucks delivering newspapers would proceed to the land behind the store as would the purveyors of other goods. Customers would park in the rear, particularly after parking on

Main Street was proscribed. The septic system which formerly served the premises was located in the rear as was a dumpster. The Town cleared the area, removed the debris and hard-topped the present parking area which encompasses most of the present parking lot and a major portion of the area without title.

14. There remains the very northerly portion of the locus which is wooded and has been little used. However, access to it is blocked on two sides by registered land so that as a practical matter it is controlled by the plaintiffs. Under the unusual circumstances of this case I find and rule that the plaintiffs have acquired title by adverse possession to it.

15. The arrangement between the Town and the then owner of the locus began in the middle sixties with a handshake. Mr. Smith granted permission to the Town to use the area behind the store (parking for Town Hall being so limited) in return for the Town's agreeing to remove the debris, brush and trees, to fill in the area and hardtop it. The arrangement has benefited both parties.

As I have set forth above, there basically are three principal issues in this litigation. There is no one who is presently a party who challenges the plaintiffs' title to the so-called Parcel 4. Since there is no dispute as to this area and since large portions of it have been used by the plaintiffs or their predecessors for the installation of the septic system, the location of a dumpster and the parking lot, I find and rule that they have acquired title by adverse possession.

So far as the two principal issues in the case, i.e., the right of way and the use of the parking lot, I have already found and ruled that there is appurtenant to the plaintiffs' land the right to use the eight foot wide portion of the driveway together, of course, with whatever portion is situated on their own land. In addition, the plaintiffs may have obtained a further prescriptive right in the remaining part of the driveway even though it is owned by a municipality as explained by Justice Wilkins in Sandwich v. Quirk, 409 Mass. 380 , 382 (1991); the difficulty, of course, with the plaintiffs' position is that the town holds the land in question for a public purpose. See also G.L. c. 260, §31, as amended by St. 1987, c. 564, §54. The parties have not argued the effect of the statute as to the westerly seven feet of the way shown on the filed plan, and it need not be reached here. I am satisfied that the parties have always recognized an easement, at least eight feet in width, as appurtenant to the plaintiffs' land, to reach the rear of the property since there is no other access to it. Since the westerly seven feet are open to the public, the plaintiffs as a practical matter can use it also even though I do not register the right to use it.

The other major issue in this case is the nature of the Town's interest in the parking lot. It is clear from Daley v. Swampscott, 11 Mass. App. Ct. 822 , 827 (1981) that a municipality may acquire an easement by prescription to use land located within its limits for a specific public purpose. As Justice Greaney said in Daley,

the test by which a municipality acquires a prescriptive easement is basically the same as that for an individual . . . any explained use for more than twenty years which is open, continuous and notorious is presumed to be adverse and conducted under claim of right (citations omitted). See G.L. c. 187, §2. Once the presumption arises, the landowner has the burden of rebutting it by showing that the use was permissive (citations omitted). In addition to these requirements it is also necessary for a municipality to establish that its acts of disseisin constitute 'corporate action.' . . .

As the cases suggest, corporate action is difficult to pinpoint, but I need not reach that question here since I find and rule that the use by the Town of the plaintiffs' land had its origin in permission granted by Mr. Smith on condition that the Town construct and maintain the parking lot which it has done. The legal rights created are very similar to a license coupled with an interest, but this category has not been argued by the parties, and I do not deal with it further. Accordingly I find and rule that the land of the plaintiff may be registered with the benefit of the right to use the easterly eight feet of the fifteen foot right of way shown on the file plan, including without limitation the right to maintain, repair and replace the existing drain and pipes therein, and subject also to such matters as may appear in the abstract but are not in issue here.

I further find and rule that the defendant Town has not acquired an easement to park on land of the plaintiffs or to require those using the parking in the rear of the building on locus must exit across the plaintiffs' land to the registered land of the Bank for Savings and the Hopkinton Acacia Club, Inc., without making an appropriate taking or obtaining an easement from the owners of the registered land and the defendants, and a declaration to such effect will be made in the Miscellaneous Case.

Judgment accordingly.

MARK D. SULLIVAN and PHYLLIS W. KEENE vs. TOWN OF HOPKINTON.

MARK D. SULLIVAN and PHYLLIS W. KEENE vs. TOWN OF HOPKINTON.