Plaintiffs filed their unverified complaint on January 19, 2010, pursuant to the provisions of G. L. c. 240 § 6, seeking to establish title and/or rights by adverse possession and/or prescription in property over an area of approximately 4,188 square feet (the Disputed Area) owned by Francis J. Frankelton and Beverly Frankelton (the Frankeltons) located at 199 Salem Street, Wilmington, MA (Defendant Property). The Frankeltons filed their Answer on March 8, 2010. A case management conference was held on April 1, 2010. [Note 1]

A pre-trial conference was held on April 25, 2011. Following a site view on September 15, 2011, a trial was held at the Middlesex Superior Court in Woburn, MA. Post-trial briefs were filed on October 28, 2011 and October 31, 2011 by the Frankeltons and Plaintiffs, respectively. The matter was then taken under advisement.

Testimony at trial was given for Plaintiff by Richard P. Kiesinger (Plaintiff), Mary F. Kiesinger (Plaintiff), Philip Kiesinger (son of Plaintiffs), Joan Harvey (daughter of Plaintiffs), and James Kiesinger (son of Plaintiffs). Testimony was given for the Frankeltons by Charles Hawley (prior owner of Defendant Property), Francis Frankelton (Defendant) and Beverly Frankelton (Defendant). Twenty-nine exhibits were submitted into evidence.

Based on the sworn pleadings, the evidence submitted at trial, and the reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, I find the following material facts:

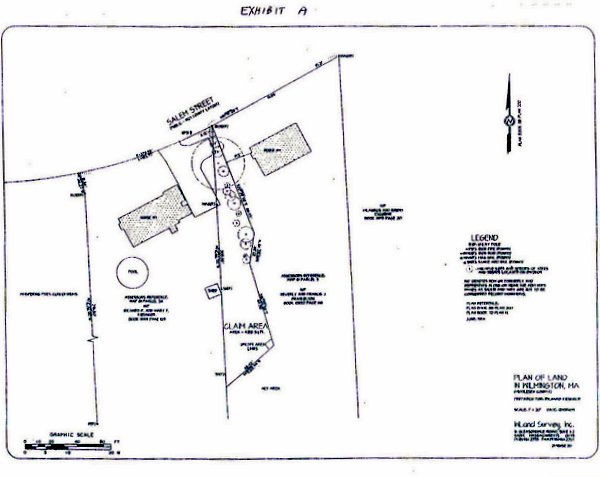

1. Plaintiffs purchased property located at 197 Salem Street, Wilmington, MA (Plaintiff Property) by deed of George Vokety and John C. Parsons dated June 2, 1958, and recorded with the Middlesex County Registry of Deeds, Northern District (the Registry) at Book 1403, Page 395. [Note 2] Plaintiff Property is shown as Lot 1-B on a plan titled Plan of Land in Wilmington, Mass. dated March 1, 1957, and prepared by Northeastern Engineering Associates (the 1957 Plan).

2. George Vokey and John C. Parsons transferred Defendant Property to Michael R. Cheripka and Elizabeth K. Cheripka by deed dated June 2, 1958, and recorded with the Registry at Book 1403, Page 391. Defendant Property is shown as Lot 1-A on the 1957 Plan. Plaintiff Property and Defendant Property abut.

3. Roger E. Vose and Gladys Vose transferred Defendant Property to Charles G. Hawley and Joanne M. Hawley by deed dated September 18, 1975, and recorded with the Registry at Book 2166, Page 202. [Note 3] The Hawleys transferred Defendant Property to Wayne J. Marshall and Laurie A. Marshall by deed dated August 15, 1986, and recorded with the Registry at Book 3649, Page 305.

4. John P. Foley and Carol H. Carfagna-Foley transferred Defendant Property to the Frankeltons by quitclaim deed dated May 31, 2000, and recorded at the Registry in Book 10852, Page 146. [Note 4]

5. At the time Plaintiffs purchased Plaintiff Property, there was a line of wooden stakes between Plaintiff Property and Defendant Property near Salem Street. Soon thereafter, Plaintiffs replaced the wooden stakes with a line of honeysuckle bushes. Michael Cheripka, then owner of Defendant Property, helped Richard Kiesinger plant the bushes, splitting the cost between them. These bushes identify the front, easterly boundary of the Disputed Area. [Note 5] Plaintiffs seeded the front of the Disputed Area within two years of their purchase of Plaintiff Property, and have continuously maintained the lawn and bushes in the front of the Disputed Area since that time. [Note 6]

6. In the early 1960s, Plaintiffs installed a shed (replaced by another shed in 1978; as shown on the 2009 Plan) that touched on the boundary line between the two properties. Plaintiffs also paved over the existing gravel driveway in the 1960s, a small portion of which was located in the Disputed Area, and would plow snow from the driveway into the Disputed Area during the winter months. In 1968, Plaintiffs purchased their first boat, storing it in the Disputed Area immediately behind their driveway. This boat was replaced by another boat in 1972, which Plaintiffs still own and store there today. During the early 1970s, Plaintiffs planted a garden in the area directly behind their boat. Plaintiffs maintained the garden for twenty years, at one point enclosing the area with chicken wire approximately 18 inches high in order to prevent animals from disturbing the plants. It is unclear when the chicken wire was installed. In the summer of 1970 or 1971, Philip Kiesinger dug a ditch approximately two feet wide and four feet deep in order to increase drainage for the septic system. A portion of this ditch was located in the Disputed Area. [Note 7]

7. At the rear of the Disputed Area was a grove of trees and wetlands. [Note 8] Plaintiffs began improving this portion of the Disputed Area in the early 1960s, when they started removing undergrowth and small trees. Larger trees were later removed as well, some requiring the use of a chain saw. The clearing resulted in an open, passable area with few, large trees, surrounded by unkept wetlands and the same dense overgrowth removed by Plaintiffs from the rear of the Disputed Area. Several piles of firewood were located in the rear of the Disputed Area beginning in the early 1980s. [Note 9] ATVs and trailers were stored and maintained in the area directly to the east of the shed, beginning at some point in the 1990s. The entirety of the yard behind the house on Plaintiff Property, including the Disputed Area, was used by Plaintiffs three children, born in 1959, 1968, and 1972, respectively, as a play area beginning in the early 1970s. When the wetlands at the rear in the Disputed Area iced over in the winter, Plaintiffs daughter would skate on the ice.

8. Shortly after the Frankeltons purchased Defendant Property in 2000, Mr. Frankelton cut down a rose bush in the Disputed Area. Plaintiffs did not object.

9. The Frankeltons had their property surveyed in 2009 and discovered the discrepancy in the boundary line. Plaintiffs had their property surveyed by InLand Survey, Inc., and the Disputed Area was shown on a plan prepared titled, Plan of Land in Wilmington, MA dated December 8, 2009 (the 2009 Plan).

****************************

Plaintiffs request a finding that their use of the Disputed Area was sufficient to meet the requirements of adverse possession. In the alternative, Plaintiffs seek a prescriptive easement for the use of the Disputed Area. The Frankeltons reject Plaintiffs arguments and challenge each element of adverse possession. The Frankeltons assert that Plaintiffs were granted permission to use the Disputed Area by a predecessor-in-interest to Defendant Property, and that Plaintiffs use of the property is insufficient to satisfy the requesite elements of adverse possession. The Frankeltons hold fee title to the Disputed Area.

I. Adverse Possession

In Massachusetts, an individual may obtain title to the land of another if he exercises actual, open, notorious, exclusive, adverse, and nonpermissive use of the property for a period in excess of twenty years. Ryan v. Starvos, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964). Whether, in a particular case, these elements are sufficiently shown is essentially a question of fact. Brandao v. DoCanto, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 156 (2011) (quoting Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961)). A party asserting its acquisition of title through adverse possession bears the burden of proving each of the necessary elements of such possession. Mendonca v. Cities Service Oil Co. of PA, 354 Mass. 323 , 327 (1968). If any required element is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Id.

I. Open and Notorious Use for 20 Years

A party making a claim of adverse possession must demonstrate uninterrupted use of the disputed property for the minimum twenty year statutory period. Hewitt v. Peterson, 232 Mass. 92 , 94 (1925); G. L. c. 260, §§ 21, 22. [S]poradic use will fail to satisfy this requirement unless the acts are sufficiently pervasive to amount to adverse possession. Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 540 (1996). The nature and the extent of occupancy required to establish a right by adverse possession vary with the character of the land, the purposes for which it is adapted, and the uses to which it has been put. LaChance v. First Natl Bank & Trust Co., 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938). Use is generally deemed open so long as it is without attempted concealment. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007). Notorious use requires that the use be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property. Id.

Plaintiffs have convinced this court that their use of the Disputed Area was sufficiently open and notorious for the requisite period of twenty years. Plaintiffs maintained the front half of the Disputed Area, which is lined with bushes, since their purchase of Plaintiff Property in the late 1950s. In so doing, Plaintiffs trimmed the honeysuckle bushes that they had planted, mowed and maintained the grass that they had seeded, and systematic[ally] raked fallen leaves. The Frankeltons predecessor-in-interest Charles Hawley took note of Plaintiffs efforts, remarking of their maintenance that, they did it all.

In 1968, Plaintiffs purchased their first boat. Plaintiffs have parked their boat and its trailer behind the driveway (and within the Disputed Area) since that time. Behind the boat, Plaintiffs maintained a garden between the years of 1970 and 1990. The garden was enclosed for several years by chicken wire measuring approximately 18 inches tall in order to prevent animals from harming the plants within it. [Note 10] In the early 1960s Plaintiffs first paved their driveway, paving it again around 1980 and encroaching on the Disputed Area. Behind the house on Plaintiff Property lies the septic system and its related leach field. Plaintiffs son was responsible for digging a trench approximately two feet wide and four feet deep through a portion of this area in order to facilitate the septic systems drainage in the early 1970s. This trench was located, in part, within the Disputed Area, near the shed.

Similar to their actions in the front portion of the Disputed Area, Plaintiffs actions beginning soon after their purchase of Plaintiff Property and continuing until this suit was initiated were sufficient to constitute open, notorious, and continuous use over the rear of the Disputed Area. At the time Plaintiffs purchased Plaintiff Property, the rear of the Disputed Area, particularly that area south of the shed, was heavily wooded; containing wetlands, trees of various sizes, and general overgrowth that effectively precluded an individual from walking through it. Plaintiffs began improving this portion of the Disputed Area soon after their purchase of Plaintiff Property in the late 1950s, beginning with the removal of light overgrowth. As time moved forward, Plaintiffs continued their improvements by removing small, and later large, trees. [Note 11] The removal of large trees during the 1960s and 1970s would often require the use of a chainsaw. Plaintiffs have maintained this area continuously since their removal of the underbrush and trees.

Having cleared the rear of the Disputed Area of several trees and other growth, Plaintiffs used the area for activities and storage. Starting in the early 1980s, Plaintiffs daughter would skate in the rear of the Disputed Area where ice would form during the winter. Children and grandchildren would often play in this portion of the Disputed Area, having been forbidden by Plaintiffs to play in front of the house on Plaintiff Property. Also beginning in the early 1980s, Plaintiffs began placing piles of firewood at various locations in the rear of the Disputed Area. Later, in the 1990s, Plaintiffs son began storing and maintaining ATVs and trailers in the rear of the Disputed Area, located directly east of the shed.

This court is convinced that Plaintiffs use of the entire Disputed Area was sufficiently open and notorious for a period of at least twenty years. Plaintiffs continuous efforts to maintain the entirety of the Disputed Area, combined with the other various uses herein mentioned, would undoubtedly have alerted the owners of Defendant Property to Plaintiffs actions there. I find that Plaintiffs use of the Disputed Area was sufficiently open and notorious for a period of at least twenty years.

II. Actual Use

In determining whether use is actual in a claim of title by adverse possession, [a] judge must examine the nature of the occupancy in relation to the character of the land. Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556 (1993) (citing Kendall, 413 Mass. at 624). The adverse possessors acts should demonstrate control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership. LaChance, 301 Mass. at 491. Actual use need not manifest itself through some form of permanent structure, so long as the use is in a manner consistent with that of typical ownership. Hurlbert v. Kidd, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 1104 (2008) (citing LaChance, 301 Mass. at 491). Thus, mowing the lawn and maintaining a row of trees, if typical activities in normal ownership, may constitute actual use. Hulbert, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 1104.

Plaintiffs utilized the Disputed Area in a manner consistent with that of any other owners use of similar lands, and have therefore met their burden regarding actual use of the property. Plaintiffs efforts in maintaining the front half of the Disputed Area, where it mowed the grass, maintained a garden, raked leaves, trimmed and planted bushes, and parked its boat were, in this courts opinion, very much consistent with the use that could be expected from a typical owner of similar property. Similarly, Plaintiffs efforts in maintaining and continuously improving the rear portion of the Disputed Area sufficiently reach the level of actual use. Plaintiffs utilized this area as any normal owner would throughout the requisite twenty year period, in many ways going beyond the use that might be expected of terrain that was choked out, such that the land was not usable or traversable, and might at one point have been best characterized as swampland. Their efforts to cut trees and clear and improve the area of dense growth were significant, and their recreational use of the Disputed Area was frequent, open, and notorious. I find that Plaintiffs have shown actual use of the Disputed Area for at least twenty years.

III. Adverse Use

A. Mens Rea in Adverse Use of the Subject Property

The Frankeltons assert that Plaintiffs claim must fail outright, given Plaintiffs admission that they believed they owned the land in question. Such a mistaken belief, it is argued, precludes a finding that Plaintiffs were using the Disputed Area in a manner truly adverse to the owners interests. The Frankeltons would therefore have this court require a showing of adverse intent, rather than simply showing adverse use.

The mental attitude of a would-be adverse possessor is irrelevant[,] where acts import an adverse character to the use of the land. Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992). In Kendall, the Supreme Judicial Court held that whether an individual believed he was building a fence upon his property or the property of another had little relevance with respect to the adverse possession claim. Rather, it was the sum of the actions taken with regard to the property that would determine whether adverse possession had occurred. Id.

This court finds the Frankeltons argument regarding the intent of a would-be adverse possessor unconvincing. Contrary to the Frankeltons assertions, no evidence exists in Massachusetts jurisprudence that operates to prevent a party from prevailing in a claim of adverse possession due to their belief, right or wrong, that they were the owners of the property in question. The relevant inquiry regarding adverse use of a disputed parcel is not whether an individual has used the parcel believing she is the owner, but rather whether the actions that took place with respect to the land were sufficiently adverse and hostile so as to put the owner on notice that the property was being used by another. I find that Plaintiffs belief that they owned the Disputed Area does not prohibit their ability to demonstrate adverse possession of the Disputed Area.

B. Adverse, Nonpermissive Use of the Subject Property

[P]ermissive use is inconsistent with adverse use. Ryan, 348 Mass. at 263. The essence of nonpermissive use is lack of consent from the true owner. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145 (2000). Whether a use is nonpermissive depends on many circumstances, including the character of the land, who benefited from the use of the land, the way the land was held and maintained, and the nature of the individual relationship between the parties claiming ownership. Id. A presumption of non-permissiveness exists where the use of the land is actual, open, and exclusive for a period of twenty years. Id. at 146.

The Frankeltons strongly suggest that any use of the Disputed Area by Plaintiffs was pursuant to permission granted by the Frankeltons predecessors in interest and therefore argue that any claim to title via adverse possession is necessarily invalid. In support of their position, the Frankeltons offered the testimony of Mr. Charles Hawley (Hawley), the record title owner of Defendant Property between September 18, 1975 and August 15, 1986. [Note 12] Hawley testified that when he purchased Defendant Property, he discussed the Kiesingers use of the Disputed Area with his seller, Mr. Vose. In that conversation, Hawley allegedly informed Mr. Vose that Plaintiffs could continue using the Disputed Area. Hawley testified that he later received thanks from Mr. Kiesinger in return. [Note 13] Mr. Kiesinger denies having ever been party to any conversations in which he was given permission to use the Disputed Area.

The Frankeltons have failed to persuade this court that Plaintiffs use of the Disputed Area was permissive. The Frankeltons proffered defense relies entirely upon the testimony of Hawley, whom this court fails to find credible based on all of the evidence. Mr. Kiesinger adamantly disputes that the alleged conversations between himself and Mr. Vose or Hawley ever took place. Hawley could provide no evidence other than his memory of the conversations between himself and Mr. Kiesinger. No documentation of this conversation exists, or was purported to have existed. No witnesses to the conversation exist.

In light of Hawleys unconvincing testimony, this court notes that the circumstances surrounding Hawleys sale of Defendant Property to the Frankeltons further support Plaintiffs contention that Hawley never provided them with permission to use the Disputed Area, and call into question whether he was even aware that the Disputed Area belonged to him in the first place. In preparing to sell his home in the mid-1980s, Hawley made no effort to remove Plaintiffs from the Disputed Area. He did not request that they remove their boatwhich was parked on his propertyor make any apparent effort to ensure that potential purchasers of his property were aware that the Disputed Area, measuring approximately 4,188 square feet, belonged to him and the property that he was selling. Hawley failed to make any such efforts despite the fact that a casual observer (or potential purchaser), might very reasonably have believed that the Disputed Area belonged to Plaintiffsparticularly in light of Hawleys admission that Plaintiffs maintained the Disputed Area exclusively, and the demarcating nature of the honeysuckle bushes.

In view of the testimonies of Mr. Kiesinger and Hawley, testimonies that were themselves in direct opposition to one another, it appears to this court that the testimony of Mr. Kiesinger, based upon the underlying facts, was more credible. No other evidence was offered by the Frankeltons to demonstrate the alleged permission granted by their predecessors in interest to Plaintiffs. I find that no permission was granted by the prior owners of Defendant Property allowing Plaintiffs to use the Disputed Area.

IV. Exclusive Use

Use of a property is exclusive when the individual exercising its actual use excludes, not only

[the] owner, but

all third persons to the extent that the owner would have excluded them. Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 557. Acts of enclosure or cultivation are evidence of exclusive possession. Id. (quoting Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 349 (1967)). Such enclosures are not necessary, however, so long as third parties are excluded in a manner similar to that which the owner would have excluded them. See id.

Plaintiffs have satisfied this court that their use of the Disputed Area was sufficiently exclusive so as to meet the requirements of adverse possession. Hawley, a former record holder of the Disputed Area, testified that the entirety of the Disputed Areas use and maintenance was undertaken by Plaintiffs. No facts were entered on the record demonstrating any use of the Disputed Area by any owner of Defendant Property between 1960 and the Frankeltons in the early 2000s.

Despite the absence of Defendant Propertys owners from the Disputed Area, the record does indicate that others, particularly neighborhood children, would sometimes traverse the property with the consent of Plaintiffs. [Note 14] Mr. Kiesinger testified that it was custom in the area for children to walk across yards rather than linger on the street. In this courts opinion, the exclusion of individuals from the Disputed Area was exactly that of the extent to which the owner would have excluded outside individuals. Plaintiffs children were to use the yard, rather than the street, and it appears from testimony that other neighborhood children would do the same, not just in the Disputed Area, but in most of the neighborhoods yards. Accordingly, it appears to this court that Plaintiffs excluded third parties, to the extent that the owner would have excluded them. I find that use of the Disputed Area was sufficiently exclusive to satisfy the requirements of adverse possession.

Having addressed Plaintiffs arguments in support of their adverse possession claim, I find that Plaintiffs established adverse possession over the entire Disputed Area.

II. Easement by Prescription

As I have determined that the Disputed Area is subject to a valid adverse possession claim, there is no need to address Plaintiffs request for an Easement by Prescription. Plaintiffs shall prepare a recordable plan of the area obtained by adverse possession (or may use the 2009 Plan, to be modified in conformance with this Decision) and shall record such plan in the Registry within sixty days of the date of this Decision.

Judgment to enter accordingly.

RICHARD P. KIESINGER and MARY F. KIESINGER vs. FRANCIS J. FRANKELTON, BEVERLY FRANKELTON and MORTGAGE FINANCIAL, INC.

RICHARD P. KIESINGER and MARY F. KIESINGER vs. FRANCIS J. FRANKELTON, BEVERLY FRANKELTON and MORTGAGE FINANCIAL, INC.