Introduction

By virtue of the instant action, initiated pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17, the plaintiffs James Hauer and Catherine Merritt-Hauer (Hauers / plaintiffs), seek judicial review of a decision by the Town of Andover Zoning Board of Appeals (Board) which served to affirm a denial by the Inspector of Buildings (Inspector / Building Inspector) for an enforcement action. The Hauers' home is located on a cul-de-sac in a residential neighborhood in the Town of Andover. Their property directly abuts that of their neighbors, the defendant intervenors, Daniel Gibson and Lynne Gibson (Gibsons / Intervenors ).

In 2005, the Gibsons commenced construction of a swimming pool and a cabana (cabana / pool house) on their property. The Hauers sought the revocation of the building permit for the cabana in late 2005 arguing that the structure violated the Andover Zoning Bylaw [Note 1] (Bylaw) inasmuch as (1) it is akin to a residential dwelling (2) located in the side yard (3) which exceeds the maximum height limitation. Acting upon the Hauer's initial appeal from the Inspector's denial of their request, the Board determined that the cabana violated the Bylaw's 1 1/2 story height limitation for an accessory structure. The Gibsons subsequently redesigned this element of the cabana [Note 2] and applied for a new building permit. The Hauers sought an enforcement action shortly thereafter that was denied by the Inspector of Buildings. They appealed that adverse ruling to the Board, which affirmed the Inspector's decision. The Hauers now seek judicial review of the Board's decision, by way of the instant action.

On June 5, 2008, the Gibsons filed a dispositive Motion for Summary Judgment. The court denied the Intervenors' Motion stating, inter alia:

"The Intervenors' Motion for Summary Judgment is hereby DENIED. It is not within this Court's province to assess the credibility of competing experts on summary judgment. Moreover, the Court is obliged to make all logically permissible inferences in favor of the non-moving party. Consequently, on the record before me, I conclude that there remain disputed facts that have yet to be fully addressed, but that have a material bearing on the disposition of the case. [Note 3]

Thereafter, on November 4, 2010, this court held a one-day trial. At the start of trial, the Hauers renewed their motion for a view and the court took said motion under advisement. A court reporter was sworn to take the testimony of Walter B. Adams and Catherine Merritt-Hauer on behalf of the Hauers, and Kaija Gilmore, Daniel Gibson, John F. Sullivan, Jr. and William S. MacLeod on behalf of the Gibsons. In a Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum (hereinafter "Memorandum"), the parties stipulated to 21 facts. This court admitted 28 exhibits into the trial record; 20 agreed and an additional 8 exhibits admitted during trial. Those exhibits are incorporated by reference into this decision for purposes of any potential appeal. At the close of plaintiffs' case, the Gibsons moved for a directed finding, which the court denied. The parties submitted their requested findings of fact and ruling of law on February 22, 2011. [Note 4]

Findings of Fact

On all testimony, exhibits, stipulations and other evidence properly introduced at trial or otherwise before it, and the inferences reasonably drawn therefrom, this court finds as follows:

The Hauers own a dwelling located at 4 Hazelwood Circle in the Town of Andover. Their direct neighbors to the east, the Gibsons, own a dwelling located at 3 Hazelwood Circle. Both dwellings have curved frontage abutting Hazelwood Circle, a cul-de-sac, and both residences are in the Single Residence B District as defined in the Bylaw. (Exhibit 17). The Gibsons' property, acquired in 1994, consists of a 40,900 square foot lot improved with a four bedroom dwelling having in excess of "5,000 square feet of living space." (Tr. 186:16-18).

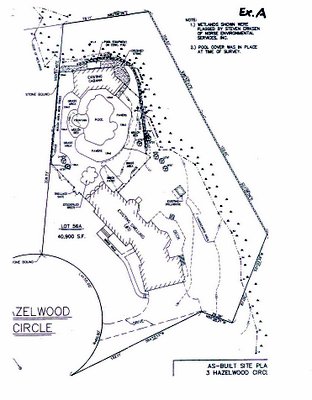

In late 2004, the Gibsons decided to build a swimming pool and cabana on their property for the benefit of their children, relatives, and friends. [Note 5] (Tr. 186-87). To this end, they engaged the services of an architect and contractor to design and build the pool house structure. (Exhibit 1; Tr. 187). On January 27, 2005, the Building Inspector granted Christian Builders Inc. a building permit (# B05-0053) for the construction of a pool house in accordance with a plan designed by Rawling Design Associates. (Memorandum, p. 6; Exhibit 1). Construction on the project did not begin until late March or early April 2005. (Tr. 123, 187). The pool house is located behind the in-ground swimming pool, is approximately 12' from the Hauers' side lot line, and is 47' wide and 18' deep. (Memorandum, p. 7-9); See attached (Exhibit A). The distance between the Hauers' dwelling and the pool house is in excess of 75 feet. [Note 6]

The Hauers did not receive direct notice of the building permit from the Town or from the Gibsons. (Tr. 122-23). In late March or early April of 2005, the Hauers observed construction activities next door at the Gibsons and contacted the Building Inspector Kaija Gilmore ("Ms. Gilmore"), to complain. [Note 7] (Tr. 122, 146-47). In early

August of 2005, when the building was nearly complete, the Hauers sent a letter of complaint regarding the ongoing construction to the Town Manager, Planning Board, Building Inspector, and Conservation Commission. (Tr. 129). On October 7, 2005, the Hauers officially requested that the Building Inspector revoke the building permit for the pool house pursuant to the Bylaw [Note 8] and G.L. c. 40A, § 7. [Note 9] (Exhibit 2). Such request was denied by the Inspector on October 20, 2005. (Exhibit 3). Pursuant to the Bylaw [Note 10] and G.L. c. 40A, §§ 8, 15, the Hauers appealed the Inspector's denial to the Board. (Exhibit 4).

At the public hearing, the Hauers argued that the cabana did not meet the town zoning requirements on grounds that it (1) is not an accessory structure, (2) is not located in the rear yard, and (3) exceeds the permissible height limitation on accessory structures. (Exhibit 4).

On June 30, 2006, the Board issued a decision (First Decision) overturning the Inspector's denial and ordering that the original building permit (# B05-0053) be revoked. (Exhibit 8). While the Board determined that the pool house was an accessory structure [Note 11] and properly located in the rear yard, [Note 12] it concluded that the cabana as built exceeded the 1 1/2 story height limitation [Note 13] specified in the Bylaw. (Exhibit 8).

Neither party appealed from the Board's First Decision. (Memorandum, p. 14). On August 10, 2006, prior to a second permit application by the Gibsons, the plaintiffs wrote the Building Inspector to inquire whether she intended to issue a formal revocation notice of the first building permit. [Note 14] (Exhibit 13.2). The Gibsons retained the services of a new firm, Galvin & Sullivan Architects, to design a plan that would remedy the height violation cited by the Board. (Exhibit 9). With their new design in hand, the Gibsons applied for a new building permit (#B06-0910) on August 16, 2006 (Exhibit 10). The application was filed by Christian Builders Inc., the original builder, and proposed to rework the existing interior structure in order to comply with the Bylaw. (Exhibit 10). A "Permit to Build" was never issued in conjunction with this application. [Note 15] (See Tr. 153154, 206).

On September 21, 2006, stating that "it is our understanding that you have issued a building permit for interior construction ...," the Hauers sent the Building Inspector an enforcement request seeking the revocation of the alleged second building permit on grounds that the pool house was in violation of the Bylaw. [Note 16] (Exhibit 11). The Inspector denied this request on September 29, 2006. (Exhibit 12). Soon thereafter, on October 10, 2006, the Hauers appealed the Inspector's denial to the Board. (Exhibit 13). On the same day that the Hauers filed with the Board (October 10, 2006), New England Design Build Inc. applied for a new building permit (# B06-1169) to "rework [the] existing structure" of the pool house. (Exhibit 14). A "Permit to Build" was issued for this application. [Note 17] (Exhibit 27; Tr. 153-154, 206).

On November 2, 2006, the Board held a public hearing "for review of a decision made by the Inspector of Buildings denying [the Hauers'] request to rescind a building permit issued for modifications to an existing accessory building." (Exhibit 16). Subsequent to the hearing but prior to the Board's decision, a "Certificate of Use and Occupancy" was issued on December 14, 2006 referencing building permit numbers B05-0053 (January 2005) and B06-1169 (October 2006). (Exhibit 26).

On December 29, 2006, the Board voted unanimously (Second Decision) to deny the Hauer's appeal which had sought the revocation of the building permit. (Exhibit 16). The Hauers commenced this action on January 18, 2007, seeking judicial review of the Board's Decision pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17. The Gibsons were given leave to intervene in this matter on February 8, 2007.

Discussion

Both parties have presented multiple arguments for this court to consider. First, as a threshold issue, the Gibsons allege that the Hauers lack standing as "persons aggrieved" to pursue their claim. Additionally, the Gibsons contend that even if the Hauers are "persons aggrieved" under the statute, two of their arguments are nevertheless barred by the doctrine of "res judicata" and by the statute of limitations under G.L. c. 40A. The Hauers respond by alleging that they have standing to bring this claim and that none of their arguments are precluded from consideration. Furthermore, the Hauers argue that the Board abused its discretion in refusing to reverse the decision of the Building Inspector inasmuch as (1) the cabana is not an accessory structure, (2) it is not situated entirely within the rear yard, and (3) it exceeds the 1 1/2 story height limitation, all as set forth in the Bylaw.

Persons Aggrieved Pursuant to G.L. c. 40A

The Gibsons allege that the Hauers do not have standing to bring this action because they have not demonstrated that they are "persons aggrieved" under G.L. c. 40A, § 17. The Hauers contend that they "currently suffer, and will continue to suffer, a deprivation of air, light and viewscape, as well as the redirection of surficial [sic] water flow as [a] result of the board's decision." For this reason, the Hauers believe their property is subject to a particularized harm separate and distinct from the general

concerns of the neighborhood as a whole. Standerwick v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 33 (2006) (stating that the plaintiff must prove "that his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community."). Accordingly, the Hauers assert they possess the requisite standing to challenge the Board's decision as "aggrieved persons."

See in this regard, G.L. c. 40A, § 17 which provides in relevant part as follows:

Any person aggrieved by a decision of the board of appeals or any special permit granting authority ... may appeal to the land court department ... by bringing an action within twenty days after the decision has been filed in the office of the city or town clerk.

A person aggrieved is one who "suffers some infringement of his legal rights." Marashlian v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996), citing Circle Lounge & Grille, Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Boston, 324 Mass. 427 , 430 (1949). Parties in interest, as defined in G.L. c. 40A, § 11, are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are persons aggrieved. See Kenner v. Zoning Board of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 117-118 (2011); G.L. c. 40A, § 11 (defining parties in interest as "abutters"). As direct abutters, the Hauers are entitled to this rebuttable presumption. See id.

The presumption stands "until the defendant comes forward with evidence to contradict that presumption." Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 34-35. This rule of evidence aids the party carrying the burden of proof by requiring the defendants to produce some evidence to the contrary. The presumption stands until such evidence to the contrary is presented. Id. at 34; See also Duggan v. Bay State St. Railway, 230 Mass. 370 , 378 (1918) ("The only legal effect of this inference is to cast upon [the defendant] the duty of producing some evidence to the contrary. When that is done the inference is at an end ....", quoting Mobile, Jackson & Kansas City R.R. v. Turnipseed, 219 U.S. 35, 43 (1910)). "A party challenging the presumption of aggrievement `must offer evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 117-18, quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 34. See also Massachusetts Guide to Evidence § 301 (d), Note (2011) ("In civil cases, presumptions ordinarily require a party against whom the presumption is directed to come forward with some evidence to rebut the presumption; they ordinarily impose a burden of production, not persuasion, on that party.")

If the presumption is successfully rebutted, the burden then rests "with the plaintiff to prove standing. Such demonstration of standing requires the plaintiffs to `establish - by direct facts and not by speculative personal opinion - that [their] injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community. "' Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33, quoting Barvenik v. Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132 (1992). However, if no evidence is presented to rebut the presumption of standing, the plaintiff is "entitled to rely entirely on their presumed status of being aggrieved parties ...." Kenner, 459 Mass. at 117-18, citing Watros v. Greater Lynn Mental Health & Retardation Association, 421 Mass. 106 , 111 (1995).

The Gibsons contend that the Hauers' presumption of standing was effectively rebutted at trial, so that the standing issue must is to be decided on all the evidence. See Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33. However, at trial, the Gibsons did not present evidence that contradicted the presumption of standing. The Gibsons rely heavily on the fact that the Hauers did "not offer any evidence that they are injured in the use or enjoyment of their property .... [and] that [n]o expert testimony was offered to tie the rainwater shown in [Exhibit 23] to the cabana." Daniel and Lynn Gibson's Post-Trial Memorandum (Gibson Memorandum), 6-7. Regardless of the Hauers' trial evidence, the Gibsons were required to produce evidence contradicting the Hauers' presumption of standing arising from their status as direct abutters. See Kenner, 459 Mass. at 118 ("A party challenging the presumption of aggrievement `must offer evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact.'", quoting Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 34). See also Massachusetts Guide to Evidence § 301 (d) (2010) ("A presumption imposes on the party against whom it is directed the burden of production to rebut or meet that presumption... If that party fails to come forward with evidence to rebut or meet the presumption, the fact is to be taken by the fact finder as established."). The Intervenors failed to rebut the presumption of standing.

The Gibsons cite testimony from two witnesses as purported contrary evidence. Gibson Memorandum, 6-7. First, they cite Mrs. Hauer's cross-examination testimony in which she states that there is now a line of arborvitae and some deciduous trees between her house and the cabana. However, when asked if they had a "clearer view [in 2005] than they do now," Mrs. Hauer responded "[y]es and no" and also stated that the line of arborvitae is not a "solid wall" (Tr. 125-126). This somewhat ambiguous testimony does not effectively contradict the Hauers' claim of a diminished view from their yard, and thus does not cause the presumption to recede. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 34-35; 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 78 Mass. App. Ct. 233 , 242 (2010) ("[The evidence] must be of a type that is credible and sufficient to rebut the particular claims of injury advanced by and abutter."), rev. granted, 459 Mass. 1104 (2011).

Secondly, the Gibsons cite the testimony of their expert, William MacLeod, a certified civil engineer and land surveyor, who testified that based on his record plans, the distance between the Hauers' residence and the cabana as built is in excess of seventy five feet. (Tr. 217). Immediately after this answer, the Gibsons' counsel ended the direct examination and the distance between the two structures was not brought up again on cross or re-direct examination. (See Tr. 218-224). This singular statement from Mr. MacLeod does not contradict any presumed fact. Mr. Macleod did not put this distance in context nor did he testify about the possible impact a structure of this size would have on a neighboring property. Cf Kenner, 459 Mass. at 121 (finding the presumption of standing receded when testimony from an architect showed that the neighbors' view was considered in the design of the structure and a civil engineer's testimony indicated the height of the new structure would not have an adverse impact on the plaintiffs); 81 Spooner Road, 78 Mass. App. Ct. at 242 ("[The party challenging standing did] not identify any expert or independent forensic evidence in the record to show it met its burden.")

Due to the Gibsons' failure to offer any convincing evidence to the contrary, the Hauers are entitled to rely upon their status as presumptively aggrieved parties. See Watros v. Greater Lynn Mental Health & Retardation Association, 421 Mass. 106 , 111 (1995) ("In this case, no evidence was presented ... that controverted the plaintiffs' presumption of standing.... [t]herefore, the plaintiffs were entitled to rely entirely on their presumed status of being aggrieved parties."); Massachusetts Guide to Evidence § 301 (d) (2010) ("If that party fails to come forward with evidence to rebut or meet the presumption, the fact is to be taken by the fact finder as established.").

Res Judicata

The Gibsons contend that two of the Hauers' claims are not properly before this court because they are barred under the doctrine of "res judicata." In the Board's first decision, it voted on three separate issues regarding the pool house: (1) whether it qualified as an accessory use, (2) whether it was located in the rear yard, and (3) whether it was 1 1/2 stories in height or less. (Exhibit 8). The Board found that the cabana qualified as an accessory use and was located in the rear yard. However, it also found that the cabana was greater than 1 1/2 stories in violation of the Bylaw's height restriction for accessory structures. Neither party sought judicial review of the Board's decision pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17. (Memorandum, p. 14). The Gibsons assert that the first two findings by the Board constitute final judgments on the merits which preclude the Hauers from now raising those arguments before this court.

"Res judicata is the generic term for various doctrines by which a judgment in one action has a binding effect in another." Heacock v. Heacock, 402 Mass. 21 , 23 n.2 (1988). The term includes both claim preclusion and issue preclusion. Kobrin v. Bd. of Registration in Med., 444 Mass. 837 , 843 (2005).

Claim preclusion "makes a valid, final judgment conclusive on the parties and their privies, and prevents relitigation of all matters that were or could have been adjudicated in the action. O'Neill v. City Manager of Cambridge, 428 Mass. 257 , 259 (1998). A party asserting claim preclusion must show: "(1) the identity or privity of the parties to the present and prior actions, (2) identity of the cause of action, and (3) prior final judgment on the merits." Kobrin, 444 Mass. at 843, quoting from DaLuz v. Department of Correction, 434 Mass. 40 , 45 (2001).

Issue preclusion "prevents relitigation of an issue determined in an earlier action where the same issue arises in a later action, based on a different claim, between the same parties or their privies." Heacock, 402 Mass. at 23 n.2. In order to preclude a party from relitigating an issue the court must conclude that (1) there was a final judgment on the merits in the prior action, (2) the party against whom preclusion is asserted was a party to that final judgment, (3) the issue in the prior litigation was identical to the current issue, and (4) the issue in the prior litigation was essential to the judgment and actually litigated. Kobrin, 444 Mass. at 843-44. The Gibsons cite both claim preclusion and issue preclusion as a bar to the Hauers' claims that the cabana is a residential dwelling located in the side yard, in violation of the Bylaw.

However, the Board's first decision does not preclude this court from considering those issues. The Board's first and second decisions were based on two separate denials by the Building Inspector and thus did not, in the view of this court, arise out of the same cause of action. Additionally, the two issues in the prior litigation were not essential to the first decision, nor is this court satisfied that there was a final judgment on the merits.

Separate Causes of Action by the Hauers

"Considerations of fairness and the requirements of efficient judicial administration dictate that an opposing party in a particular action as well as the court is entitled to be free from continuing attempts to relitigate the same claim." Baby Furniture Warehouse Store, Inc. v. Meubles D&F, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 27 , 33 (2009), quoting Wright Machine Corp. V. Seaman-Andwall Corp., 364 Mass. 683 , 688 (1974). "A claim is the same for res judicata purposes if it is derived from the same transaction or series of connected transactions." Saint Louis v. Baystate Medical Center, Inc., 30 Mass. App. Ct. 393 , 399 (1991), citing Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 24 (1). "What factual grouping constitutes a 'transaction', and what groupings constitute a 'series', are to be determined pragmatically." Id., quoting Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 24(2). This determination takes into account whether the facts are "related in origin or motivation and whether they form a convenient trial unit ...." Charlette v. Charlette Brothers Foundry, Inc., 59 Mass. App. Ct. 34 , 44 (2003). An action in a different form of liability is not a different cause of action if it arises out of the same transaction or acts and seeks to redress the same wrong. TLT Construction Corp. v. A. Anthony Tappe & Associates, 48 Mass. App. Ct. 1 , 8 (1999) ("The statement of a different form of liability is not a different cause of action, provided it grows out of the same transaction, act, agreement, and seeks redress for the same wrong.")

A comparison of the Hauers' two appeals demonstrates that their claims are predicated upon different actions by the Building Inspector, ie. claims that seek to redress two different alleged wrongs. The Hauers' 2005 appeal sought to overturn the Inspector's Decision of October 20, 2005 in which she refused to rescind a building permit issued in January of 2005. (Exhibit 3-5). The Hauers' 2006 appeal sought to overturn the Inspector's September 29, 2006 denial of the Hauers' request for an enforcement action. (Exhibit 13). While both actions share some common facts, they arise out of two completely different acts by Ms. Gilmore. Compare Exhibit 3 with Exhibit 13.2. Thus, they are not the same claim. See TLT Constr. Corp., 48 Mass. App. Ct. at 8 (stating that identical cause of action arise "out of the same transaction, act, agreement, and seeks redress for the same wrong.")

The First Decision Was Not a Final Judgment

Both claim preclusion and issue preclusion require a final judgment on the merits. See Kobrin, 444 Mass. at 843 ("The invocation of claim preclusion requires ... prior final judgment on the merits."); Tuper v. North Adams Ambulance Service, Inc., 428 Mass. 132 , 134 (1998) ("Before a party will be precluded from relitigating an issue, a court must determine that there was a final judgment on the merits in the prior adjudication ...."). A judgment is considered final when the parties are fully heard at a hearing, the decision is supported by a "reasoned opinion", and the decision was subject to review or was reviewed. See Tausevich v. Board of Appeals of Stoughton, 402 Mass. 146 , 149 (1988) ("Factors supporting the conclusion that a decision is final for the purpose of preclusion are that the parties were fully heard, the judge's decision is supported by a reasoned opinion, and the earlier opinion was subject to review or was in fact reviewed.", citing Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 13 comment g (1982)).

The Board qualifies as an equivalent to a "court of competent jurisdiction." Tuper, 428 Mass. at 135 ("The prior adjudication need not have been before a court. If the conditions for preclusion are otherwise met, a final order of an administrative agency in an adjudicatory proceeding precludes relitigation of the same issues between the same parties, just as would a final judgment of a court of competent jurisdiction.")

However, Massachusetts case law is unsettled on the issue of whether all decisions of zoning boards of appeal under G.L. c. 40A constitute a final judgment on the merits. See Petrillo v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Cohasset, 65 Mass. App. Ct. 453 , 456-57 n. 9 (2006) ("[W]e explicitly do not decide that all decisions of a zoning board of appeals (on special permits, variances, or otherwise) qualify as final determinations, because of various provisions in the Zoning Act (G. L. c. 40A) that bear on finality, ... the potential for further consideration of applications, and the potential for reconsideration, upon matters initially denied (G. L. c. 40A, § 16)."). In this case, "the potential for further consideration of applications" by the Board must be taken into account and this court finds that the June 2006 decision was not a final judgment by the Board. See id.

A final judgment must be "the `last word' of the rendering court ...." Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 13 & comment a (1982) ("This section makes the general commonsense point that such conclusive carry-over effect should not be accorded a judgment which is considered merely tentative in the very action in which it was rendered. On the contrary, the judgment must ordinarily be a firm and stable one, the `last word' of the rendering court - a 'final' judgment."). At the June 1, 2006 public hearing, the construction on the cabana was for the most part complete. However, the petitioner was not seeking the absolute demolition of the structure. To the contrary, the Hauers' counsel requested the Board to revoke the original building permit and order "modifications" to the structure. [Note 18] (See Exhibit 8, at 3). Additionally, at the public hearing, Mr. Hauer himself stated that "he is not asking that the building be demolished, only that it be modified to comply with the zoning bylaw." (See Exhibit 8, at 4).

The remedy sought by the Hauers indicates that the Board's decision was not meant to be "the final word" on the structure since it was known that the Gibsons would attempt to modify the structure within the parameters of the Bylaw and re-apply for a new building permit. See Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 13 & comment b (1982) ("[A] judgment will ordinarily be considered final in respect to a claim ... if it is not tentative, provisional, or contingent and represents the completion of all steps in the adjudication of the claim by the court.... Finality will be lacking if an issue of law or fact essential to the adjudication of the claim has been reserved for future determination ....").

Additionally, a judgment is not final if judicial review of the prior decision was not available. Sena v. Commonwealth, 417 Mass. 250 , 260 (1994) ("We have implied that for a decision to be final it must have been subject to appeal or actually reviewed on appeal.... We now state conclusively that for collateral estoppel to preclude litigation of an issue, there must have been available some avenue for review of the prior ruling on the issue."). Yet, the Hauers most likely did not have the ability to seek judicial review of the Board's 2005 first decision. See Jarosz v. Palmer, 436 Mass. 526 , 533 (2002) ("The opportunity for review ... was so remote that we cannot say that the order is subject to review for purposes of issue preclusion."). In order to seek judicial review under G.L. C. 40A, § 17, the Hauers must have been "persons aggrieved." The Hauers, in the most basic sense, were not aggrieved by the Board's decision. The building permit they challenged was revoked and they prevailed. Cf. Taylor v. Board of Appeals of Lexington, 451 Mass. 270 , 274 (2008) ("In this action, the abutters challenged the comprehensive permit that was originally issued by the board in 2003, requesting that a judge in the Superior Court annul the board's decision issuing the comprehensive permit. The original comprehensive permit is inoperative.... They no longer have any personal stake in the validity of the board's decision. We agree with the judge that the case is moot.") Therefore, the Board's 2005 decision was not subject to judicial review by the Hauers and thus was not final.

The Two Issues Were Not Essential to the Board's First Decision

Finally, in order for a decision in prior litigation to have preclusive effect, the decision must have affected the outcome of the case. See Jarosz, 436 Mass. at 533 ("For a ruling to have preclusive effect, it must have a bearing on the outcome of the case. `If issues are determined but the judgment is not dependent upon the determinations, relitigation of those issues in a subsequent action between the parties is not precluded. " quoting Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 27 comment h (1982)). The finding must be regarded by the court and the party to be bound "as essential to a determination on the merits, and not merely essential to a determination of the narrow issue before the court at that time." Id.

Accordingly, the only essential issue in the Board's first decision concerned the determination that the building permit was invalid, inasmuch as the height of the pool house was in violation of the Bylaw. The other two issues, relating as they did to the structure's use and location, did not affect the outcome of the case as they were essentially rendered moot by the Board's determination. Thus, the Board's first decision as it related to the use and location of the pool house, was not essential to the outcome of the appeal.

For the foregoing reasons, neither claim preclusion nor issue preclusion will serve to prevent the Hauers from obtaining a de novo judicial review of the case at bar. See G.L. c. 40A, § 17.

Are Plaintiffs' Claims Time Barred?

Finally, the Gibsons assert that this court does not have jurisdiction over two of the Hauers' claims [Note 19] because they are time barred under G.L. c. 40A, § 7. (Daniel and Lynn Gibson's Post-Trial Memorandum, 9-10). In this regard, although the Hauers received no record notice of the first building permit, the Gibsons argue that the Hauers had reasonable notice of its issuance by at least April of 2005, and that they should have challenged the building permit earlier than they did. Although the Gibsons' argument lacks support because the originally building permit was found to be invalid by the Board, see infra, this court will nonetheless consider the timeliness of the Hauers' claim.

"[W]hen a party with adequate notice of the issuance of a building permit claims to be aggrieved by the permit on the ground that it violates the zoning code, the party must file an administrative appeal within thirty days of the permit's issuance; a failure to do so deprives the board or other permit granting authority, and later the courts, of jurisdiction to consider the appeal." Connors v. Annino, 460 Mass. 790 , 797 (2011). See also Gallivan v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Wellesley, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 850 , 857 (2008) ("[A] party with adequate notice of an order or decision that violates a zoning provision must appeal that order or decision to the appropriate permit granting authority within the thirty-day period allotted for such an appeal.").

However, if a party is without adequate notice of an order or decision, it may, in appropriate circumstances, pursue an "enforcement request under G.L. c. 40A, § 7, and a subsequent appeal from a denial of said request under G.L. c. 40A, §§ 8 and 15 ...." Connors, 460 Mass. at 797. An enforcement action is a written request to the Inspector of Buildings to enforce the Bylaw against persons who are alleged to be in violation thereof See G.L. c. 40A, § 7 ("If the officer or board charged with enforcement of zoning ordinances or by-laws is requested in writing to enforce such ordinances or bylaws against any person allegedly in violation of the same and such officer or board declines to act, he shall notify, in writing, the party requesting such enforcement of any action or refusal to act, and the reasons therefore, within fourteen days of receipt of such request.")

The 2005 Building Permit

The Gibsons contend that the Hauers failed to timely appeal the first building permit issued in 2005. This argument stems from trial testimony that suggests the Hauers had notice of the building permit when construction of the pool house commenced in March or April of 2005. The Gibsons argue that the construction gave the Hauers reasonable notice and therefore they were not entitled to wait to seek an enforcement request. This argument fails for several reasons.

First, the Hauers' 2005 enforcement request is not within the scope of this courts' judicial review. The Hauers are not seeking judicial review of the Board's first decision. Neither party appealed the Board's revocation of the first building permit. (Memorandum, ¶ 14) The Hauers complaint seeks relief from the Board's rejection of their September 2006 enforcement request and subsequent administrative appeal. See G.L. C. 40A, § 17 ("Any person aggrieved by a decision of the board of appeals ... may appeal to the land court department ... by bringing an action within twenty days after the decision has been filed ...."(emphasis added)).

Thus any review regarding the Board's jurisdiction to hear the first appeal is not a matter for this court to consider. See Conservation Commission of Falmouth v. Pacheco, 49 Mass. App. Ct. 737 , 741 (2000) ("[the defendant] did not embrace the opportunity afforded him to take a timely appeal ... for a de novo review of the commission's action ... Having forgone his opportunity to do so, he is precluded from relitigating his jurisdictional contention.").

Additionally, the Hauers were without notice of the first building permit for nearly two months. (Tr. 123) Record notice was not provided them and construction on the cabana did not begin for almost sixty days after the building permit was issued. (Memorandum, ¶ 7). Thus, they lacked notice within the thirty day period that the building permit had issued. Connors, 460 Mass. at 795-96 ("[A]n enforcement request may still be pursued under § 7 if the aggrieved party can establish that he or she was without adequate notice of the order or decision being challenged."). Therefore, the Hauers were entitled to pursue an enforcement action under G.L. c. 40A, § 7 because they did not have adequate notice of the Inspector of Building's decision within the thirty day timeframe. Id. ("[T]he alternative remedy offered in § 7 of requesting the enforcement of the zoning ordinance [is] only available where the aggrieved party does not have adequate notice of the building permit's issuance in time to challenge it within thirty days."); Gallivan v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Wellesley, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 850 , 857 (2008) ("If a § 15 appeal were the sole remedy for a party aggrieved, the recipient of a permit could keep the permit under wraps for thirty days and then would have succeeded in foreclosing any challenge. ", quoting Fitch v. Board of Appeals of Concord, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 748 , 750-753 (2002)); Elio v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Barnstable, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 424 , 428 (2002) ("[S]uch an alternative remedy is necessary because persons aggrieved by the issuance of a building permit or other order may not even know of the permit or order until the appeal period has expired. This is because no notice of the permit or order to interested third persons is required.").

The 2006 Building Permit

While the first appeal is not before this court, the timeliness of the Hauers' second appeal is a jurisdictional threshold the court must examine before it may consider the merits of the Hauers' claims. See Connors, 460 Mass. at 797 (finding that a failure to file a timely appeal "deprives the board or other permit granting authority, and later the courts, of jurisdiction to consider the appeal."). The Hauers assert that two different building permits were issued by the Building Inspector in 2006, one in August and another in October. Plaintiffs' Post-Trial Memorandum, and Request for Findings of Fact and Rulings of Law, 7. ("The Building Inspector subsequently issued two new building permits, one on August 16, 2006, and a second on October 10, 2006."). However, this conclusion lacks support. Testimony at trial from the Inspector established that the only Permit to Build for interior alterations to the cabana was issued in October of 2006. [Note 20] (Tr. 153-54, 206). All that existed prior to October 10, 2006 was an application for a building permit. (Exhibit 10). Accordingly, at the point in time of the Hauers' September 21, 2006 letter, the building permit in question had not yet been issued, and thus, there was no order or decision to appeal under G.L. c. 40A § 8. See Connors, 460 Mass at 794 ("With respect to a building permit, the date of its issuance is considered the date of the order or decision. For purposes of § 8, the issuance of a building permit qualifies as an order or decision of the inspector of buildings, or other administrative official.") (internal citations omitted). Consequently, the Hauers were not precluded from seeking an enforcement action thirty five days after the Gibsons completed the August 2006 building permit application.

In this regard, the September 21, 2006 letter, while perhaps flawed, qualifies nonetheless, as a request for enforcement under G.L. c. 40A, § 7. A request for enforcement is a request in writing made to the zoning officer for enforcement of the zoning bylaws against persons who are alleged to be in violation of the said bylaws. ("If the officer or board charged with enforcement of zoning ordinances or by-laws is requested in writing to enforce such ordinances or by-laws against any person allegedly in violation of the same and such officer ... declines to act, he shall notify, in writing, the party requesting such enforcement of any action or refusal to act, and the reasons therefore ...."). The Hauers' enforcement letter meets this definition. It asks that the

Building Inspector construe it as formal enforcement request and alleges that the Gibsons' pool house is in violation of the Bylaw. (Exhibit 11).

When the Hauers made their request, the cabana's original building permit had been revoked. The then existing structure was in violation of the zoning code and was, therefore, subject to an enforcement action. See Connors, 460 Mass. at 799 ("[G.L. C. 40A, § 7] first paragraph, ... indicates that the Legislature intended the claimed violation already to have occurred, not that it was anticipated to occur in the future."). Accordingly, the letter and subsequent denial provided an appropriate basis for an enforcement action appeal under G.L. c. 40A, § 8. See Vokes v. Avery W. Lovell, Inc., 18 Mass. App. Ct. 471 , 482-483 (1984) (finding that the Zoning Act grants "a right to request the officer charged with enforcing local zoning to enforce the by-law under G.L. C. 40A, § 7, and, if the requesting party is aggrieved by the inspector's decision, a right to seek administrative relief from the board under G.L. c. 40A, §§ 8 and 15, and, after exhausting administrative remedies, a right to obtain judicial review pursuant to G.L. C. 40A, § 17."). The Inspector responded with a denial on September 29, 2006 and the Hauers filed their appeal on October 10, 2006, well within the time frame specified by G.L. c. 40A, § 8. See Connors, 460 Mass. at 794 ("With respect to an appeal from an "inability to obtain [a § 7] enforcement action" the date from which the thirty-day period for appeal is measured is the date of the written response of the municipal building official to the aggrieved person's request for enforcement."). In view of the foregoing, this court concludes that it possesses the requisite jurisdiction to proceed under G.L. c. 40A, § 17.

The Board's Findings

The Hauers seek to annul the Board's second decision which effectively denied their enforcement request concerning the pool house. The Hauers contend that the Board's decision was predicated upon an interpretation of the bylaw that was legally untenable. They contend as well, that the Board acted in excess of its authority. More specifically, the Hauers argue that the cabana violates the zoning bylaw because it constitutes the equivalent of a dwelling rather than an accessory structure. In the alternative, the Hauers contend that the cabana does not meet the dimensional requirements of an accessory structure because it is located in the side yard and is greater than 1 1/2 stories in height. See Bylaw § 4.2.2 ("The minimum requirements for yard depth shall not preclude the placing of accessory buildings in such minimum yard area, provided that the same (a) are located in the rear yard; (b) are not over one and one-half stories in height; ...."). The board found the cabana to be an accessory structure in compliance with all requirements. (Exhibit 16).

Standard of Review

"Review of a board's decision ... pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, § 17, involves a "peculiar" combination of de novo and deferential analyses." Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of New York, Inc. v. Board of Appeal of Billerica, 454 Mass. 374 , 381 (2009), citing Pendergast v. Board of Appeals of Barnstable, 331 Mass. 555 , 558 (1954). The court grants some measure of deference to the board's legal conclusions but fact finding is a de novo review. Mellendick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Edgartown, 69 Mass. App. Ct. 852 , 857 (2007). "While a judge is to give `no evidentiary weight' to the board's factual findings, the decision of a board `cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground' or is based on an `unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary' exercise of its judgment in applying land use regulation to the facts as found by the judge" Wendy's Old Fashioned Hamburgers of New York, Inc., 454 Mass. at 381-82, quoting Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 487 (1999).

"The reasonable construction that [the Board] gives to the by-laws it is charged with implementing is entitled to deference." Cameron v. DiVirgilio, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 24 , 29 (2002). To determine the meaning of a bylaw, the court looks to "the ordinary principles of statutory construction." Framingham Clinic, Inc. v. Zoning Rd of Appeals, 382 Mass. 283 , 290 (1981). Under this standard, the bylaw's language is the "principal source of insight into legislative intent." Water Dep't of Fairhaven v. Department of Envtl. Protection, 455 Mass. 740 , 744 (2010). When the meaning of the language is plain and unambiguous the court enforces the bylaw according to its plain wording. Adoption of Daisy, 460 Mass. 72 , 76 (2011).

In the case of Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile, 429 Mass. 478 , 485-486 (1999), when discussing the appropriate standard of review, the Court observed as follows:

Massachusetts is one of several states that provide for de novo review of local zoning authority decisions. On appeal..., [however] a judge determines the legal validity of the zoning board decision on the facts found by him; he gives no evidentiary weight to the board's findings. Judicial review is nevertheless circumscribed: the decision of the board `cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary.' (internal citations omitted).

Thus, although this court makes its findings de novo, it must accord the Board below due deference, and not reverse unless the Board's decision appears unreasonable in light of those findings. See MacGibbon v. Board of Appeals of Duxbury, 356 Mass. 635 , 639 (1970) (holding special permit decision must be affirmed unless "based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary").

In the case at bar, this court is satisfied that the Board construed its own Bylaw, in a reasonable fashion. The plaintiffs have failed to demonstrate that the Board exceeded its authority by refusing to overturn the decision of the Building Inspector. The Hauers primarily contend that the pool house stands in violation of the Bylaw because it is a residential dwelling and not an accessory structure. Additionally, they argue that even if the cabana is an accessory structure, it is located in the side yard and exceeds 1 1/2 stories in height, all in violation of the Bylaw requirements for accessory structures. See Bylaw § 4.2.2 ("The minimum requirements ... shall not preclude the placing of accessory buildings ... provided that the same (a) are located in the rear yard; (b) are not over one and one-half stories in height ...").

For the reasons set out below, this court concludes that pool house is in compliance with the Bylaw inasmuch as it is an accessory structure of 1/ 1/2 stories, located in the rear yard.

The Cabana is an Accessory Structure

Pursuant to the Bylaw, an accessory building is defined as "[a] detached subordinate building located on the same lot with a principal building, use of which is an accessory use as herein defined." It is undisputed that the cabana is a detached building located on the same lot as the Gibsons' residence which is the principal building on the lot. See (Memorandum, p. 1-6; Tr. 186); Bylaw § 10 (defining principal building as "[t]he building in which is conducted the principal use of the lot on which said building is situated."). Therefore, the sole issue before the court in this regard, is whether the pool house qualifies as an accessory use under the Bylaw. It is the view of this court, that it does so qualify.

As noted supra, an accessory use is one "which is subordinate to, clearly incidental to, customary in connection with, and located on the same lot as, the principal use." Bylaw, § 10. We have seen moreover, that the cabana is located on the same lot as the Gibson's single family residence, the principal structure thereon. See (Memorandum, ¶ 2-6; Tr. 186); See § 10 (defining principal use as "[t]he primary or predominant use of any lot or parcel."). Furthermore, for the reasons set forth below, the use of the cabana is incidental to, subordinate to, and customary with, the principal use of the lot as a single family home.

The Cabana is Incidental and Subordinate to the Primary Residential Use

An accessory use must remain incidental to the principal residential use of the property. Cunha v. City of New Bedford, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 407 , 411 (1999) "The word `incidental means that the use must not be the primary use of the property but rather one which is subordinate and minor in significance. " Id., quoting Henry v. Board of Appeals of Dunstable, 418 Mass. 841 , 845 (1994). See also Old Colony Council - Boy Scouts of America v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Plymouth, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 46 , 48 (1991) ("The ordinary lexical meaning of incidental also connotes something minor or of lesser importance."); Black's Law Dictionary 1439 (7th ed. 1999) (defining subordinate as "[p]laced in or belonging to a lower rank, class, or position"). Additionally, when used to define an accessory use, the term incidental must "also incorporate the concept of reasonable relationship with the primary use." Henry, 418 Mass. at 845. Here,

Ample evidence at trial established that the pool house is of a lesser significance and reasonably related to the use of the property for residential purposes. The Gibsons' dwelling sits on a lot having an outdoor swimming pool. (Tr. 186). The cabana is utilized by them in connection with their recreational use of the swimming pool. (Tr. 188). Cf Simmons v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 60 Mass. App. Ct. 5 , 10 (2003) ("The undisputed facts establish that the defendants' stable and three horses are subordinate and incidental to the primary use of the land. Their home is situated on the lot, and their horses are used by family members and guests for recreational purposes ...."). According to Mr. Gibson, the cabana and swimming pool are used to entertain family and friends who visit their home. (Tr. 186-87). The cabana is a place where people go to wash their towels and bathing suits or watch TV while using the swimming pool. (Tr. 188).

This use is reasonably related to the primary residential use of their property. Cf Simmons, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 10 ("The keeping of pets is, of course, reasonably related to the primary residential use of the property."); See Bylaw § 4.2.2 (a swimming pool is a permitted accessory use). Additionally, unlike their dwelling, the outdoor swimming pool may realistically be enjoyed during certain seasons of the year. Therefore, the use of the cabana and swimming pool can be deemed to be far less intense and of a relatively minor nature, when compared to the use of the dwelling. See Cunha v. City of New Bedford, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 407 , 411 (1999) ("While an hour by hour comparison would be unwise, the clear disproportion between the principal use and the accessory use makes apparent that the use of the property as a professional office is incidental to the plaintiffs use of the property as a residence."). Accordingly, the use of the pool house is both incidental and subordinate to the primary use of the lot.

The Use of the Cabana is Customary

"[A]n accessory use needs to be both customary and incidental." Simmons, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 10; See Bylaw, § 10 (defining accessory use as "[a] use which is subordinate to, clearly incidental to, customary in connection with, and located on the same lot as, the principal use."). According to the Supreme Judicial Court:

The word 'customarily' is even more difficult to apply. Although it is used in this and many other ordinances as a modifier of 'incidental,' it should be applied as a separate and distinct test. Courts have often held that use of the word 'customarily' places a duty on the board or court to determine whether it is usual to maintain the use in question in connection with the primary use of the land... .

In applying the test of custom, we feel that some of the factors which should be taken into consideration are the size of the lot in question, the nature of the primary use, the use made of the adjacent lots by neighbors and the economic structure of the area."

Harvard v. Maxant, 360 Mass. 432 , 438-39 (1971).

Evidence at trial established that a cabana is customary in connection with the principal residential use of the lot. In this regard, the plaintiffs' own expert, Walter B. Adams, testified as follows on cross examination:

Q You would agree that a pool house or cabana is an acceptable-is an accessory use to a dwelling?

A Yes, it is.

Q You can have a pool house or a cabana?

A Yes, you can.

Q And it's not inconsistent with the use of the building as a pool house or cabana to have a bathroom and a shower in it; is it?

A It is not inconsistent. [Note 21]

Additionally, under the bylaw, recreational structures are permitted as accessory uses. Bylaw § 4.2.2. Finally the fact that the Board found the cabana to be customary is a factor taken into consideration since this court extends a "measure of deference to the determinations of local officials on issues of local enforcement, particularly where the essential question requires a factual determination of what is customary." Simmons, 60 Mass. App. Ct. at 10, citing Sacco v. Inspector of Bldgs. of Brockton, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 749 , 749-50 (1975).

In this regard, this court finds that the testimony of intervenor Daniel Gibson on direct examination was not only credible but uncontroverted, as well.

With regard to the pool house, Mr. Gibson testified in relevant part, as follows:

We have used it as an adjunct to the pool. It's a place where people, if they have towels and bathing suits, they can be washed. We have a TV out there so the kids can watch shows and things like that.

Q And you have a refrigerator in that building?

A We have only one refrigerator in the building.

Q There aren't two refrigerators? [Note 22]

A No....

Q What do you use the refrigerator for?

A We have soft drinks for... people who will be using the cabana....

Q Is there any stove in that area?

A There has never been a stove, and one has never been in that building.

Q Is there an oven?

A No.

Q Is there a cutout in that counter for a stove or an oven?

A No

Q Or in the cabinets?

A No.

Q Is there a 220 outlet installed under that counter or in the vicinity of that counter for the purpose of putting in a stove or an oven?

A No [Note 23]

Q Or at all?

A No.

Q Is there a hot plate or microwave?

A No.

Q Is there a toaster oven?

A No.

Q Have there ever been facilities placed in that building to cook?

A No.

Q Do you have any intention of putting in any cooking facilities in that building?

A No.

Q To your knowledge, has anyone ever spent the night sleeping in that building?

A No one has....

Q Now if you have guests stay at your house, do they ever sleep in that cabana?

A No.

Q Now there's a washer and dryer in there, isn't there?

A Yes.

Q And what's that used for?

A For bathing suits, towels.

Q In conjunction with the pool?

A Yes. [Note 24]

For their part, the Hauers argue that the cabana is not an accessory building at all, but tantamount to a second dwelling, an impermissible use under the Bylaw. A dwelling unit is defined in the Bylaw as "[o]ne or more rooms, designed, occupied, or intended for occupancy as a separate living quarter, with cooking, sleeping, and sanitary facilities provided within the dwelling unit for the exclusive use of a single family maintaining a household." Bylaw, § 10.

The Hauers argument fails on several accounts. First, the evidence adduced at trial satisfactorily established that the Gibsons do not occupy or intend to occupy the cabana as separate living quarters. (Tr. 191-92). Second, there are no sleeping facilities within the cabana. (Tr. 190). Finally, there are no cooking facilities within the cabana. (Tr. 188-90). For these reasons, the court is satisfied that the cabana as designed, built, and currently used is not intended for occupancy "as a separate living quarter... for the exclusive use of a single family maintaining a household." It is this court's view that the pool house constitutes not a residential dwelling but an accessory structure, one that is customary, subordinate, and wholly incidental to the primary residential use on the Gibson's property.

The Cabana is Located in the Rear Yard

Based upon the clear and unambiguous language of the Bylaw, this court is satisfied that the pool house is located in the rear yard. See Adoption of Daisy, 460 Mass. 72 , 76 (2011) (Where the meaning of the language is plain and unambiguous, we will not look to extrinsic evidence of legislative intent "unless a literal construction would yield an absurd or unworkable result."). Andover divides the area of its lots into three categories for the purposes of zoning regulation: "front yard", "rear yard", and "side yard". Bylaw, §10.

A rear yard is defined as "an open space extending the full width of the lot between the rear lot line and the nearest point of the principal building on the lot." [Note 25] Id. (emphasis added)

Lot width, in turn, is defined as "[t]he horizontal distance between side lot lines, measured parallel to the lot frontage." Id. (emphasis added)

Lot Frontage is defined as, "[a]n uninterrupted distance along a single way ...." Id.

Exhibit 15 is a site plan of the lot at issue, incorporating the property lines, the Gibsons' home, the pool house, and Hazelwood Circle, in relevant part. See attached (Exhibit A). Those who testified regarding the location of the pool house were in agreement regarding the lot lines that constitute both the rear yard lines and the side yard lines. The rear lot lines may be identified as the northern most lines marked 78.11', 104.57', and 122.01'. (Tr. 46, 178, 214).

The west side lot line may be identified by the line marked 208.73.' (Tr. 49; Tr. 214)

The east side lot line may be identified by the lines marked 87.0', 29.38', 132.11'. (Tr. 88:12-16; Tr. 214).

Although the Gibson's lot is uniquely shaped, classifying the areas of the property in accordance with the Bylaw is fairly straightforward. (See Exhibit 15). As defined, the rear yard is the open space that extends the full width of the lot between the rear lot line and the nearest point of the Gibsons' house. Because the definition references the full width of the lot, the rear yard is determined by drawing a straight line from the rear points of the Gibsons' house to the closest side lot lines. The area within those lines, the rear of the Gibsons' house, the side lot lines, and the rear lot lines, all encompass the rear yard. (See Exhibit 28). Therefore, since the cabana is located in this area, it is located in the rear yard of the Gibson's lot.

The Cabana is One-and-One-half Stories in Height

A half story is defined in § 10 of the Bylaw as "[a] partial story under a gable, gambrel or hip roof, the wall plates of which on any two sides do not rise more than four feet above the floor of such partial story." (emphasis added) One of the Gibsons' expert witnesses, architect John F. Sullivan, Jr. [Note 26] offered the following definition of a "wall plate."

A wall plate is defined in the Mass. State Building Code as a horizontal member connecting the vertical studs. It's either a single wall plate or a double wall plate. It's the top of the wall, of an exterior wall. [Note 27]

It should be observed in this regard, that the term "wall plate" is nowhere defined in the Bylaw. However, of relevance is the introductory paragraph of § 10 thereof, [Note 28] which concludes as follows:

Terms and words not defined herein but defined in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts state building code shall have the meaning given therein unless a contrary intention is clearly evident in this by-law.

For his part, Mr. Adams, the plaintiffs' expert testified somewhat unconvincingly on direct examination, as follows:

Q...[I]s the term "wall plates" something that's defined in these standard works that are utilized by architects? [Note 29]

A I don't recall that the term "wall plate" is defined in those terms-in those documents.

Q Do you have an understanding as to the common meaning and usage of the term "wall plates" among architects?

A Yes.

Q What is it?

A A wall plate is a vertical or-it defines a plane representing a vertical or near vertical wall surface. It's to identify the plane of the wall.

Q So the wall plate is not necessarily something that's physical or tangible; is that correct?

A Correct.

The following relevant exchange took place in the course of Mr. Sullivan's direct examination:

Q...You're understanding is that that-when it [the Bylaw] says "two sides," it's referring to the exterior sides of the building?

A Exactly, exactly.

Undisputed testimony was presented at trial that the cabana has a gable. [Note 30] (Tr. 175, 197). [Note 31] The floor of the loft was also established as the horizontal band that is identified as "Existing Loft Floor" on Exhibit 9. (Tr. 61).

Based on all the testimony and the exhibits, the court finds that only one wall plate exceeds four feet and that the Board properly classified the mezzanine or loft as being no more than half a story. The only wall plate in excess of four feet is the gable wall next to the stair way. (Tr. 64, 198; Exhibit 9). Two other wall plates, one on the front side and one on the back side, are exactly four feet in height. (Tr. 64, 199-200).

According to Mr. Sullivan: [Note 32]

[t]here's a wall at the front of the loft facing the pool area, whose measurement is exactly 4 feet. There is a wall in the back of [a] closet that heads at 4 feet. (emphasis added)

That is to say, they do not rise more than four feet above the floor of the mezzanine or loft.

The parties disagree on whether the sloped ceiling from the first floor constitutes a wall plate that is restricted in height. (See Exhibit 9). However, pursuant to the Bylaw,

only the side wall plates are restricted in height. See Bylaw § 10 (defining half story as "[a] partial story under a gable, gambrel or hip roof, the wall plates of which on any two sides do not rise more than four feet above the floor of such partial story.") (emphasis added).

In this regard, Mr. Sullivan testified as follows in response to inquiries by the court:

Q: And what of the sloped ceiling / wall?

A This is the cathedral ceiling for the bathroom down below,...

Q And why is that not a wall plate?

A... [T]his is an interior element of the back side of the cathedral ceiling. It doesn't touch the exterior wall. (emphasis added)

Based on the plain wording of the Bylaw, this court concludes that the interior sloped ceiling is not an exterior element or side of the structure. Thus, it does not, under any circumstances, constitute a wall plate that must be less than four feet in height.

As a consequence, the pool house was properly classified by the Board as being no more than 1 1/2 stories in height.

Motion for a View

The Hauers Motion for a View was taken under advisement by this court at the outset of trial. (Tr. 12). A view of the cabana would have been especially helpful in evaluating the Gibsons' claim that the Hauers were not "persons aggrieved" pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17. However, inasmuch as this court has determined that the Gibsons failed to rebut the Hauers' presumption of standing, the court deems it unnecessary to take a view under the circumstances pertaining herein. Therefore, the plaintiffs' Motion is hereby denied.

Conclusion

In view of the foregoing, this court concludes that the Board did not act in excess of its authority, nor did it act in a manner that was arbitrary, capricious, whimsical or legally untenable. Accordingly, the Town of Andover Zoning Board of Appeals Decision dated December 29, 2006, will be Affirmed. [Note 33] The plaintiffs' complaint will be Dismissed.

This court has found the facts in detail and rendered rulings of law in this decision. Proposed findings of fact and rulings of law are hereby adopted to the extent they are consistent herewith, but are otherwise denied.

Judgment to issue accordingly.

A: This is a duplicate of a permit that was issued earlier in October ... [and] [i]t authorizes interior alterations." (Tr. 153-54). (See also Tr. 201)

However, see Tr. 176:7-19, in which Mr. Adams acknowledged that he had never been in the pool house and did not know if the Gibsons had ever been asked to provide him with access.

JAMES HAUER and CATHERINE MERRITT-HAUER v. DANIEL S. CASPER, CAROL C. MCDONOUGH, PAUL D. BEVACQUA, DAVID W. BROWN, LYNNE S. BATCHELDER, STEPHEN D. ANDERSON, and PETER F. REILLY as members of the TOWN OF ANDOVER ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS and DANIEL and LYNN GIBSON

JAMES HAUER and CATHERINE MERRITT-HAUER v. DANIEL S. CASPER, CAROL C. MCDONOUGH, PAUL D. BEVACQUA, DAVID W. BROWN, LYNNE S. BATCHELDER, STEPHEN D. ANDERSON, and PETER F. REILLY as members of the TOWN OF ANDOVER ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS and DANIEL and LYNN GIBSON