Introduction

Margaret Lazarus, Renner Wunderlich, Ralph Lang and Nancy Lang (the plaintiffs) take issue with those of their neighbors who claim to have a right to use a 15 way abutting their property to access the waters of the Eastham Town Cove on foot and by vehicle. The neighbors, James H. Knowles and Anne Hobday (the defendants) own a summer home in the Eastham neighborhood and claim they have a right to utilize the way in order to launch and store their dinghies, park their vehicles, and moor their boats in the waters off the way. The plaintiffs assert they own the fee in the entire way, while defendant James H. Knowles claims to own the fee in the southwestern half of the 15 way. Defendant Anne Hobday also claims to have an express easement right over the 15 way that is appurtenant to her property. The plaintiffs disagree.

On January 13, 2010, the plaintiffs filed a one count verified complaint seeking to quite title pursuant to G.L. c. 240, §§6-10 in a 15 right of way abutting their property. The way is located directly between the plaintiffs lots and allows access to the Town Cove. The plaintiffs are seeking a declaration that they are the owners in fee simple of the 15 way by operation of the Derelict Fee Statute. See G.L. c. 183, §58. Additionally, the plaintiffs seek a declaration that neither defendant has any ownership rights or easement right in the disputed way. They ask, as well, that the defendants be permanently enjoined from trespassing or otherwise entering upon the Way. [Note 1]

On March 5, 2010, the defendants filed an answer and a verified counterclaim seeking three separate declarations of rights under G.L. c. 231A. Count one of that counterclaim alleges that the developer, Warren Corliss, retained a fee interest in the 15 right of way and that his heirs conveyed that fee in 2008 to defendant James H. Knowles. In addition, count one also alleges that defendant Anne Hobday holds a deeded easement over the 15 right of way that is appurtenant to her land. Count two of the counterclaim alleges title by prescription and count three alleges title by estoppel.

On July 12, 2010, the plaintiffs filed a motion for partial summary judgment on the sole count of their complaint. On August 20, 2010, the defendants filed an opposition and cross-motion for partial summary judgment on count one of their counterclaim. Thereafter, on October 21, 2010, the motions were heard and taken under advisement.

Summary Judgment Standard

Summary judgment is appropriate when the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c); Cassesso v. Commr of Corr., 390 Mass. 419 , 422 (1983); Cmty Natl Bank v. Dawes, 369 Mass. 550 , 553 (1976). A fact is genuinely in dispute only if the evidence is such that a reasonable jury could return a verdict for the non-moving party. Anderson v. Liberty Loby, Inc., 447 U.S. 242, 248 (1986). Material facts are those that might affect the outcome of the case under governing law. Id. The moving party bears the burden of demonstrating affirmatively the absence of a triable issue, and its entitlement to judgment as a matter of law. Pederson v. Time, Inc., 404 Mass. 14 , 16-17 (1989). In viewing the record before it, the Court reviews the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party. Donaldson v. Farrakhan, 436 Mass. 94 , 96 (2002).

On the present record, this court concludes that there is no genuine dispute of material fact as to the issues addressed and resolved herein. Consequently, the matter is ripe for summary judgment. For the reasons stated below, the plaintiffs motion for partial summary judgment will be allowed while the defendants cross-motion for summary judgment will be denied.

Background

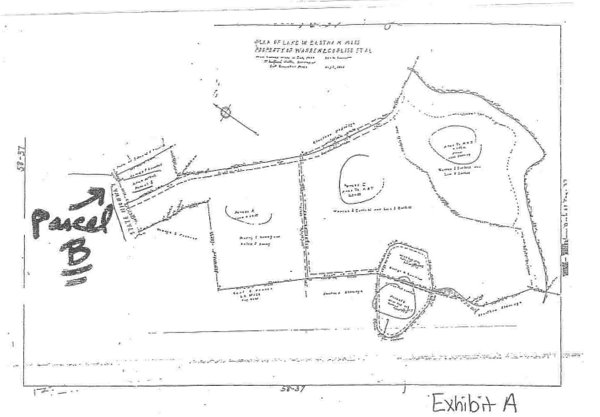

In June of 1938, the Knowles family [Note 2] conveyed property in Eastham, known as the James P. Knowles homestead, to Warren Corliss, subject to an $800 mortgage held by the Cape Cod Five Cents Savings Bank. [Note 3] The property is located between the state highway (now Route 6) and the Town Cove. In August of 1938, Warren Corliss recorded a plan that split the land into five distinct parcels. (Exhibit A). In the same month, by two separate deeds (both for consideration of less than $100), Warren and Lois Corliss (the Corlisses) conveyed the northwest lot (known as Parcel B) and the southeast lot (known as Parcel C) on the 1938 plan to James P. Knowles, father of the defendants. Parcel Bs deed conveyed an easement over Parcel A for access to the state highway and also granted James P. Knowles a personal right to use an eighteen foot right of way over the Corlisses land to the Town Cove and the right to use its beach. Furthermore, Parcel Cs deed contained an easement over Parcel A and Parcel D for access to the state highway.

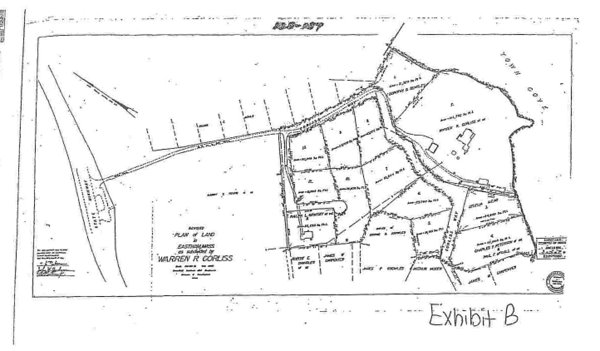

In June of 1952, the Corlisses recorded a plan to further subdivide Parcel D and the unmarked coastal parcel into thirteen different lots. (Exhibit B) On June 17, 1952, James P. Knowles released to the Corliss family all rights of way over that portion of said 18 foot right of way extended from the Town Cove in a westerly direction a distance of one hundred seventy five (175) feet . . . . The next day, the Corlisses granted to James P. Knowles, a right of way over Corliss Way, a distance of 485 feet from the right of way granted to him in 1938, to a 10 right of way leading from Corliss Way in a Southeasterly direction to the Town Cove, and the use, for foot passage only, of said ten foot way . . . . A short time later, the Corlisses conveyed Lot 1, the lot which James P. Knowles prior easement burdened, to Dorothy Bentley.

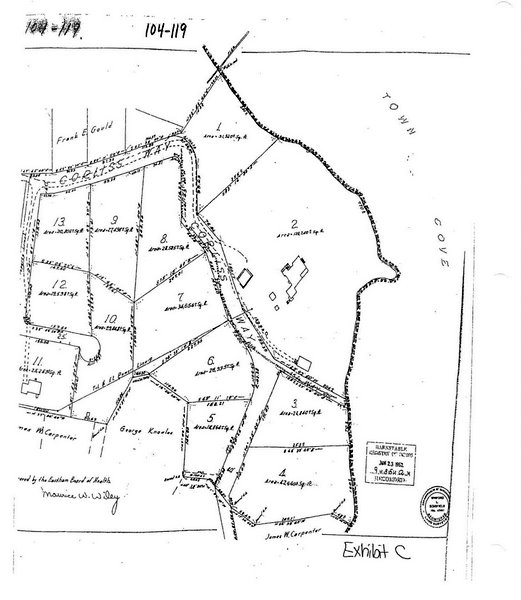

The Corlisses recorded a revised subdivision plan in January of 1956 that made only minor changes to the 1952 plan. (Exhibit C). On either July 31, 1953 or 1957, [Note 4] James P. Knowles and George Knowles released all their easement rights to the Corlisses in exchange for a right of way over Corliss Way and over a 10 foot way on the southern part of Lot 5 leading to the cranberry lots then owned by George D. Knowles and James P. Knowles. [Note 5]

Plaintiffs Ownership

In 1955, Lot 3 was sold to the plaintiffs predecessors in title, Cecilia Mead. Lot 3 has frontage directly along the southwest side of the disputed 15 way. The deed contains a running description of the lot. [Note 6] The description starts at a cement bound at the junction of the 40 way, Corliss Way, and the 15 way and runs southeast by the southwesterly line of said 15 Way one hundred eighty-five feet (185), more or less to the town cove. In 1995, the lot was conveyed to plaintiffs Renner Wunderlich and Margaret Lazarus with a deed using the exact same lot description.

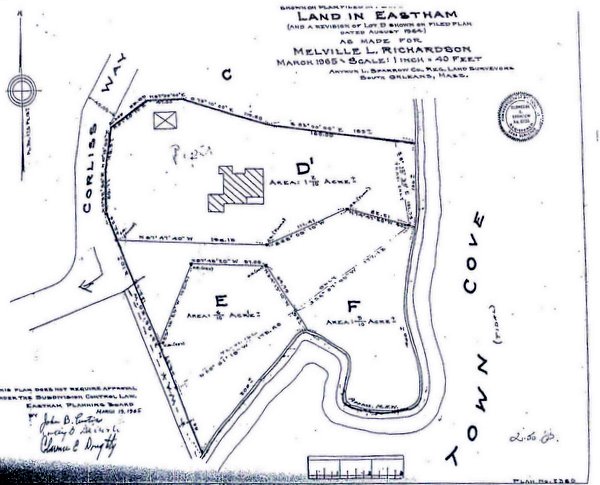

In 1959, the Corlisses conveyed to Melville and Esther Richardson five lots, including Lot 2, which is bordered by the disputed 15 way on its western boundary. [Note 7] Lot 2s deed contains a bounding description and states [o]n the West, by a fifteen foot way and by Corliss Way, seven hundred seventy-four and 37/100 (774.37) feet. [Note 8] In 1965, the Richardsons further subdivided Lot 2 and sold the southern lot that borders the 15 way, Lot E, to Roger and Louise Kimball for $80,000. (Exhibit D). The deed contains a running description and conveyed land by the Northeast line of said way . . . one hundred forty and 07/100 (140.07) feet, more or less, to Town Cove, a tidal inlet. Louise Kimball passed away in 1991 and devised Lot E to both her daughter, one of the plaintiffs, Nancy (Kimball) Lang, and her son, Gordon Kimball. Subsequently in 1993, for consideration of $80,000, Gordon Kimball conveyed all his interest in Lot E to plaintiff Nancy (Kimball) Lang. [Note 9]

Defendants Ownership

In 1984, James P. Knowles conveyed both his and George Knowles interest in the cranberry bog lots to David and Elizabeth Fleming. James P. Knowles passed away in 2005 and left a life estate in his remaining land (Parcel B) to Genevieve Knowles, and the remainder to the defendants, his children, James H. Knowles and Anne Hobday. Subsequently, both Genevieve Knowles and James H. Knowles conveyed their interest in Parcel B to Anne Hobday. The interest was then conveyed by Anne Hobday to herself and her husband, Edward Hobday, as tenants by the entirety. [Note 10]

In 2008, the two heirs of William and Lois Corliss, each conveyed a separate quitclaim deed to James H. Knowles granting any right, title, and interest in the fee underlying the way . . . shown as the 15 Way in consideration for $100. James H. Knowles asserts these deeds give him a fee interest in the southwestern half of the way.

Discussion

An action to quiet title under G.L. c. 240, § 10 is an action in rem brought under the court's equity jurisdiction. See G.L. c. 185, § 1 (k). "[I]n equity the general doctrine is well settled, that a bill to remove a cloud from the land ... [requires that] both actual possession and the legal title are united in the plaintiff." First Baptist Church of Sharon v. Harper, 191 Mass. 196 , 209 (1906). In this case, the plaintiffs claim actual possession of the land and legal title. Possession is implied because it is undisputed the plaintiffs reside on both lots abutting the way. The plaintiffs claim legal title to the way by operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, G.L. c. 183, §58.

A party seeking declaratory judgment under G.L. c. 231A must "set forth a real dispute caused by the assertion by one party of a legal relation or status or right in which he has a definite interest and the denial of such assertion by the other party, where the circumstances . . . indicate that, unless a determination is had, subsequent litigation as to the identical subject matter will ensue." Hogan v. Hogan, 320 Mass. 658 , 662 (1947). [A]n express purpose of declaratory judgment is to afford relief from . . . uncertainty and insecurity with respect to rights, duties, status and other legal relations. Boston v. Keene Corp., 406 Mass. 301 , 304-05 (1989), quoting G.L. c. 231A, § 9. In count one of their counterclaim, the defendants seek to resolve the same issues as the plaintiffs: (1) the ownership of the fee interest in the 15 way; and (2) the express easement rights of the defendants, if any. Each issue will be discussed in turn.

Application of the Derelict Fee Statute (G.L. c. 183, §58)

The Derelict Fee Statute sets out an authoritative rule of construction for instruments passing title to real estate abutting a way. Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. 489 , 492 (1976). The statute mandates that every deed of real estate abutting a way includes the fee interest of the grantor in the way to the centerline of the road if the grantor retains property on the other side of the way or for the full width if he does not unless `the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding a side line.'" Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 243 (1992), quoting G.L.c. 183, § 58 (emphasis added). [Note 11] The term abutting means property with frontage along the length of a way. Emery v. Crowley, 371 Mass. 489 , 494 (1976). The way needs to be in existence on the ground or contemplated and sufficiently designated as a proposed way at the time of conveyance. Hanson v. Cadwell Crossing, LLC., 66 Mass. App. Ct. 497 , 502 (2006). In order to determine if a way is sufficiently contemplated or designated, reference may be made to the plan. Hanson v. Cadwell Crossing, LLC., 66 Mass. App. Ct. 497 , 502 (2006), quoting Murphy v. Mart Realty of Brockton, Inc., 348 Mass. 675 , 678 (1965).

The statute is retroactively applied to all prior instruments with two exceptions, [Note 12] neither of which is relevant to this dispute. Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 803 (2003); Adams v. Planning Bd of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 388 (retroactively applying the Derelict Fee Statute to a 1957 deed). The Legislature passed the law in order to quite title to sundry narrow strips of land that formed the boundaries of other tracts . . . . Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 803 (2003). The statute was enacted to remedy the common law situation where a grantor has conveyed away all of his land abutting a way or stream, but has unknowingly failed to convey any interest he may have in land under the way or stream, thus apparently retaining ownership of a strip of the way or stream. Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 803 (2003), quoting 1971 House Doc. No. 5306 (returning bill for further amendment).

The statute codified the basic common law principle that presumed the grantors intent to convey land to the center of a way if the land directly abutted the way. Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 243 (1992). Under the common law, if the description in the conveyance described the boundary as being on or by a way, with no restrictions or exceptions, it was presumed the grantor was conveying title to the center of the way.

Casella v. Sneierson, 325 Mass. 85 , 89 (1949), citing Erickson v. Ames, 264 Mass. 436 , 442-45 (1928); Salem v. Salem Gas Light Co., 241 Mass. 438 , 441 (1922); Gray v. Kelly, 194 Mass. 533 , 536-37 (1907). The common law presumption could be overcome by proof of a contrary intent ascertained from the words used in the written instrument in the light of all the attendant facts. Suburban Land Co. v. Billerica, 314 Mass. 184 , 189 (1943). This exception enabled grantors to prove their intent to reserve the fee in an abutting way by describing the boundary in the written instrument as being on or by the sideline of said way. See Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 804 (2003) (emphasis added).

However, the Derelict Fee Statute is stricter than the common law rule which it codified and superseded. McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 694 (2010). The statutory presumption that title in the abutting way is conveyed to the grantee is conclusive unless the instrument passing title evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation. Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 243-44 (1992). Other attendant evidence of the parties intent is not permitted. Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 244 (1992). Nor may that intent be proved, as it could under the common law, by language that the property is bounded by a side line of a way. Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 804 (2003) (emphasis added).

Plaintiffs Own the Fee Interest in the 15 Way that is Adjacent to Their Property, Out to the Low Water Mark

By operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, title in the 15 way passed to the Corlisses grantees. In assessing the rights of the parties to the fee in the disputed way, it should be observed that, immediately prior to 1955, the Corlisses owned the entirety of the fee in the way. In 1955, they conveyed Lot 3 (which has frontage on the 15 way) to Celia Mead with a deed containing a running description of the lot which runs southeast by the southwesterly line of the 15 way to the Town Cove. As the statute explicitly states, in order to preserve the fee interest of a grantor in a way, the deed must evidence a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding by a side line. G.L. c. 183, §58 (b) (emphasis added)

In the case at bar, the deed contains only the written term bounding by the southwesterly line. It does not expressly reserve the grantors interest in the way as is required under the statute. Additionally, the deed does not grant an easement in the 15 right of way; It does , however, grant easements respectively in the 40 way, Corliss Way, and the 18 foot way to the state highway. Cf McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 697 (2010) ([H]ad the grantors intended to . . . pass the fee to the center of the way, it would have been unnecessary to grant [the grantees] any easement at all.). Accordingly, the fee from the southwest lot line to the center of the way was conveyed to Celia Mead. See G.L. c. 183, §58 (a)(ii) (At this time, the Corlisses still owned the lot on the other side of the 15 way). As stated above, in 1995 the lot was conveyed to plaintiffs Margaret Lazarus and Renner Wunderlich using the exact same lot description. This conveyance granted them fee ownership to the center of the way.

Plaintiffs Ralph and Nancy Lang own the northeastern half of the way that directly abuts their property. In 1959, the Corlisses conveyed multiple lots, including lot 2, to Esther and Melville Richardson. The deed contains a bounding description and recites [o]n the West, by a fifteen foot way and by Corliss Way, seven hundred seventy-four and 37/100 (774.37) feet. Under G.L. c. 183, §58, the Corlisses conveyed all their fee interest in the way, which was to the center line. [Note 13] Subsequently, the lot was further subdivided by the Richardsons and in 1965 Melville Richardson, as a widower, conveyed what is currently known as Lot E to Roger and Louise Kimball. Lot E is on the southwest corner of Lot 2 and directly abuts the 15way and the Town Cove. The deed contained a running description and conveyed land running by the Northeast line of said way . . . one hundred forty and 07/100 (140.07) feet, more or less, to Town Cove, a tidal inlet. By operation of the Derelict Fee Statute, the deed conveyed the fee in the 15 way abutting their property to the center of the way. See G.L. c. 183, §58. As stated above, the Kimball interest eventually passed to the Lang plaintiffs. Accordingly, the Langs own the way that abuts their property to the center line.

Massachusetts property law provides that every owner of land bounded on tidal waters, such as the landowners here, enjoys title to the shore and to the adjacent tidal flats all the way to the low water mark or one hundred rods, whichever is less. See Boston Waterfront Dev. Corp. v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 , 633-637 (1979). See also Pazolt v. Director of the Div. of Marine Fisheries, 417 Mass. 565 , 571 (1994). ("[A] grant of land bounding on the sea shore carries the flats, in the absence of excluding words.") However an owner may separate his upland from his flats, by alienating the one, without the other. But such a conveyance is to be proved, not presumed, and therefore ordinarily proof of the title in the upland thus bounded carries with it evidence of title in the flats." Pazolt v. Director of the Div. of Marine Fisheries, 417 Mass. 565 , 570-71 (1994), quoting Valentine v. Piper, 22 Pick. 85 , 94 (1839).

In this case, the plaintiffs are fee owners of the 15 way which is adjacent to the shore line. The defendants have not presented any evidence that the Corlisses separated their ownership of the uplands from the flats adjacent to the way. Therefore, the plaintiffs own the title (conditioned by the public right of navigation) to the disputed shore area and the adjacent tidal flats all the way to the low water mark. Boston Waterfront Dev. Corp. v. Commonwealth, 378 Mass. 629 , 635-36 (1979). Thus, plaintiffs Margaret Lazarus and Renner Wunderlich own the fee interest in the southwesterly half of the 15 way out to the low water mark. So too, the plaintiffs Ralph and Nancy Lang own the fee interest in the northeasterly half of the 15 way that is adjacent to their property out to the low water mark.

Defendant James H. Knowles Was Not Deprived of Property Rights

The quitclaim deeds obtained by defendant James H. Knowles in 2008 did not convey any ownership rights in the 15 way. As discussed above, by operation of law, the rights in the fee were conveyed in the 1950s by the Corlisses to the plaintiffs predecessors in title. The defendants argue that the Corliss heirs conveyed to them their retained interest in the 15 way. They primarily assert that the language used in the 1950 deeds was sufficient to retain the fee interest in the southwest half of the 15 way. Additionally, they argue that circumstances attendant to the conveyances of the Corlisses and subsequent grantors, evidence the intent to retain the fee interest in the 15 way. Unfortunately for the defendants, the statutory law supercedes the common law upon which they rely, and does not therefore permit other attendant evidence of the parties intent. Rowley v. Massachusetts Elec. Co., 438 Mass. 798 , 804 (2003) (Nor may that intent be proved, as it could under the common law, by language that the property is bounded by a side line of a way.); McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 694 (2010) (stating that the Derelict Fee Statute is stricter than the common law rule which it codified and superseded.); Tattan v. Kurlan, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 239 , 244 (1992) (Other attendant evidence of the parties' intent is no longer probative.).

Furthermore the defendants claim that as applied in this case, the retroactive application of the Derelict Fee Statute completely deprives them of their property rights in violation of the due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment and of Articles 1, 10, and 12 of the Declaration of Rights of the Constitution of the Commonwealth. They assert that the retroactive application of the statute in this case is unreasonable, and thus, unconstitutional. See American Mfrs. Mut. Ins. Co. v. Commissioner of Ins., 374 Mass. 181 , 189-91 (1978).

As a preliminary matter, it should be noted that the statute has been applied retroactively by the Appeals Court. See Adams v. Planning Bd. of Westwood, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 383 , 388 (2005). Furthermore, property rights grounded in the common law are subject to retroactive changes by the Legislature. See Nantucket Conservation Found. V. Russell Mgmt., 380 Mass. 212 , 217 (1980) ([T]he nature of the specific property rights at issue here undercuts the . . . claim that the statute is unreasonable. The . . . rights in the way were grounded on a rule of common law and therefore carried with them implicit notice that they might be modified in the face of changing conditions.). In a case whose facts mirror those in the instant matter, a judge of this court rejected a constitutional challenge to the retroactive application of the Derelict Fee Statute. Buteau v. Hebard, 11 LCR 267 , 269 (2003) (Sands, J) (General Laws c. 183, § 58 appears to meet the requirements of the reasonableness test, particularly since the property right which Defendants are trying to protect (retention of the fee rights in the Disputed Parcel) is merely the presumed intent of the grantor based on the "side line" language in the deed, rather than the general common law presumption that a grantor intended to pass title to the center of the way . . . . ).

However, in this case we need not examine the reasonableness of the statute because the defendants do not possess a property interest in the 15 way, and so cannot claim to have been unconstitutionally deprived of their property rights in that way. It is well settled that a grantor can only convey the title he possesses. See Bevilacqua v. Rodriquez, 460 Mass. 762 (2011); Bongaards v. Millen, 440 Mass. 10 , 15 (2003) (Where, as here, the grantor has nothing to convey, a mutual intent to convey and receive title to the property is beside the point. The purported conveyance is a nullity.). Consequently, the Corliss heirs inherited no fee interest in the 15 way from their parents, and thus, had nothing to convey to the defendants. Compare Buteau, 11 LCR at 268 (defendants received their property in 1968, prior to the enactment of the G.L. c. 183, §58).

If any persons could be said to have standing to assert a due process claim of that nature, it presumably would have been the Corlisses. See Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 US 606, 628 (2001) ([I]t is a general rule of the law of eminent domain that any award goes to the owner at the time of the taking, and that the right to compensation is not passed to a subsequent purchaser.). The Derelict Fee Statute was enacted in 1972, and thus the alleged taking took place by operation of law during the Corlisses alleged ownership. See New England Continental Media, Inc. v. Milton, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 374 , 377 (1992) ([T]he plaintiff has no standing to challenge the validity of the 1965 taking. That right belonged only to the holder of the easement at the time of the taking.) The Corlisses could perhaps have initiated a due process claim or possibly a claim for reformation of the deed. See McGovern v. McGovern, 77 Mass. App. Ct. 688 , 699 (2010) (holding that courts can apply the equitable doctrine of reformation to the effects of the operation of G.L. c. 183, §58 . . . .). There is nothing in the record to suggest the Corlisses attempted to do so.

It is an established rule in Massachusetts that [o]rdinarily one may not claim standing . . . to vindicate the constitutional rights of some third party. Blixt v. Blixt, 437 Mass. 649 , 661 (2002), quoting Salma v. Attorney General, 384 Mass. 620 , 624 (1980). Courts will not grant standing to parties seeking to protect or enforce the rights of a non-party, particularly when that non-party could have protected their own rights. Globe Newspaper Co. v. Superior Court, 383 Mass. 838 , 842 n. 5 (1981). In order to have standing, the defendants are required to show that the challenged action has caused [them] injury. Slama, 384 Mass. at 624.

The defendants have failed to show that the operation of the Derelict Fee Statute has caused them a particular harm or injury. See id. By 2008, the statute had been in existence for over thirty-five years. [Note 14] The defendants were on notice that the fee in the 15 way passed to the plaintiffs predecessors in title. Cf Lamson & Co. v. Abrams, 305 Mass. 238 , 244 (1940) (The purpose of the recording statute, G.L. c. 183, § 4, is to show the condition of the title to a parcel of land and to protect purchasers from conveyances that are not recorded and of which they have no notice.) The quitclaim deeds they obtained conveyed to them no fee interest in the 15 way and no right to initiate legal action in place of the Corlisses. See Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 US 606, 628 (2001).

Defendant Anne Hobdays Purported Easement Rights as Owner of Parcel B

Regardless of the fee ownership in the disputed way, defendant Anne Hobday argues that she has an express easement in the disputed way by virtue of a 1957 deed from the Corlisses to her father, James P. Knowles. The conveyance in question was a release and exchange of rights by the Knowles and the Corlisses. Because of a previous grant, James P. Knowles had a primary access routes to his cranberry bog lot from the Northwest over the Corlisses land from the state highway. That right of way was granted in the 1938 deed conveying him the cranberry bog adjacent to George Knowles lot. James P. Knowles also had a personal easement that extended from Parcel B to the Town Cove.

It is undisputed that the Knowles exchanged both these right of ways, which they describe in the deed as being appurtenant to [their] cranberry bogs for a single right of way over Corliss Way to a 10 right of way on southern end of Lot 5 leading to the cranberry bog lots. James P. Knowles subsequently sold the cranberry bog lots to the Fleming family. The plaintiffs contend that the deeded easement does not include the 15 right of way and even if it did, the easement is appurtenant only to the cranberry bogs that neither of the defendants own. The defendants contend that the easement not only includes the 15 way, but it is also appurtenant to Parcel B, the property currently owned by defendant Anne Hobday. For the reasons stated below, defendant Anne Hobday has no claim to the express easement because the easement is appurtenant to the cranberry bog lots.

The Deeded Easement is Not Appurtenant to Anne Hobdays Property, Parcel B

"An easement is an interest in land which grants to one person the right to use or enjoy land owned by another." Commercial Wharf E. Condominium Assn. v. Waterfront Parking Corp., 407 Mass. 123 , 133 (1990). A right of way provides rights of ingress, egress, and travel over the land subject to the easement. See Crullen v. Edison Elec. Illuminating Co., 254 Mass. 93 , 94 (1925); Nantucket Conservation Found., v. Russell Mgmt., 380 Mass. 212 , 216 (1980). "An easement is appurtenant to land when the easement is created to benefit and does benefit the possessor of the land in his use of the land." Schwartzman v. Schoening, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 220 , 223 (1996), quoting Restatement of Property § 453 (1944).

The meaning of the conveyance is to be determined by the language of the grant construed in the light of the attending circumstances which have a legitimate tendency to show the intention of the parties as to the extent and character of the contemplated use of the way. Doody v. Spurr, 315 Mass. 129 , 133 (1943). [W]ith respect to an easement created by a conveyance . . . the language [used] . . . is the primary source for the ascertainment of the meaning of [the] conveyance." Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998), quoting Restatement of Property §483 comment d. "The use made of the servient tenement at the time of the conveyance is a factor to be considered in determining the extent of the easement created." Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 174 (1948).

Though defendants have the burden of proof, they fail to present sufficient facts in support of their argument that the express easement is appurtenant to Parcel B and not to the cranberry bog lots. Duddy v. Mankewich, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 62 , 66 (2009) (As the party claiming an easement or right of way, it is well settled that the defendant bears the burden of proving its existence.) They simply state [w]hile the rights being released are referenced as appurtenant to the cranberry bog, the rights being conveyed are not described as being appurtenant to any specific parcel and could apply either to the cranberry parcel or the Knowles Homestead . . . . Defendants Opposition to Plaintiffs Motion for Partial Summary Judgment and Cross-Motion For Partial Summary Judgment, 18. Because of the express language of the deed and the surrounding circumstances of the conveyance, the dominant estate for purposes of the easement consists of the cranberry bog lots and not Parcel B.

First, the express language of the conveyance evidences an intent that the easement benefit the cranberry bog lots. The conveyance describes James P. Knowles and George Knowles as owners of the cranberry bog lots shown on the 1938 plan. Wellwood v. Havrah Mishna Anshi Sphard Cemetery Corp., 254 Mass. 350 , 354 (1926) (A plan referred to in a deed becomes a part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed.). It does not reference James P. Knowles ownership of Parcel B which is on the same plan. Also, the rights being released in exchange for new rights are explicitly described as rights of way appurtenant to the cranberry bogs. See Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998) (stating that the language used by the written instrument is the primary source for determining the meaning of the conveyance).

Second, the surrounding circumstances evidence the grantors intent that the easement benefit the cranberry bog lots. The easement is granted to both James P. Knowles and George Knowles. George Knowles owned only an interest in the cranberry bog lots and had no interest in Parcel B. He gave up his right of way retained in the 1938 deed in exchange for this new route to access his land. To interpret the grant as conveying an appurtenant easement to Parcel B while conveying George Knowles nothing would be illogical. See Doody v. Spurr, 315 Mass. 129 , 133 (1943) ([T]he language of the grant construed in the light of the attending circumstances . . . have a legitimate tendency to show the intention of the parties . . .).

Finally, the easement granted is an ingress and egress easement for the benefit of the cranberry bog lots. The only reason the easement burdens Lot 5 is to allow access to the cranberry bogs from Corliss Way. Hodgkins v. Bianchini, 323 Mass. 169 , 174 (1948) (The use made of the servient tenement at the time of the conveyance is a factor to be considered . . .). How this access would benefit Parcel B is unclear and the defendants have not offered any explanation. See Schwartzman v. Schoening, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 220 , 223 (1996). See the recent case of DeNardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 361 (2009 citing the Restatement of Property § 453, comment b (1944) (In order that an easement may be appurtenant to a particular tract of land, not only must it appear that the easement was created for the purpose of benefiting the possessor of that land in his use of it, but the use permitted by the easement must be such as really to benefit its owner as the possessor of that tract of land).

For these reasons, the easement is appurtenant to the cranberry bog lots and provides access to same from the main highway via Corliss Way. Because the easement is appurtenant to the cranberry bog lots and not Parcel B, the defendant Anne Hobday has no claim to an express easement. [Note 15]

Conclusion

In view of the foregoing, this court concludes that the plaintiffs each own a fee interest to the centerline of the 15 way to the extent that the way abuts their respective properties. This court further concludes that the individual defendants possess no ownership rights in the way nor do they enjoy any express easement rights therein.

Accordingly, it is hereby

ORDERED that the plaintiffs Motion for Partial Summary Judgment is hereby ALLOWED to the extent specified herein. It is further

ORDERED that defendant Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment is hereby DENIED. It is further

ORDERED that the matter will be set for trial on counts 2 and 3 of defendants counterclaim.

SO ORDERED

By the court (Grossman, J.)

MARGARET LAZARUS, RENNER WUNDERLICH, RALPH LANG, and NANCY LANG v. JAMES H. KNOWLES and ANNE M. HOBDAY

MARGARET LAZARUS, RENNER WUNDERLICH, RALPH LANG, and NANCY LANG v. JAMES H. KNOWLES and ANNE M. HOBDAY