Richard and Marilyn Bazarian (Bazarians), owners of property known as 10 Shaume Road in Falmouth, initiated this action on June 11, 2008, by filing a Complaint against their abutters, Ronald and Pamela Khachadoorian (Khachadoorians), owners of property known as 6 Shaume Road. Plaintiffs Complaint seeks to quiet title pursuant to G. L. c. 240 § 6, alleging they have established title to an area roughly ten feet wide by one hundred fifty-six feet long that forms the most easterly portion of the Khachadoorians property and runs parallel to the record boundary line between the parties properties. The Khachadoorians answered on June 26, 2008, challenging the sufficiency of Plaintiffs adverse possession claim and asserting several affirmative defenses, including equitable estoppel, unclean hands, laches, and waiver. The Khachadoorians moved for summary judgment on the issue of estoppel. A hearing on that motion was held on August 17, 2009, with the court issuing an Order Denying Khachadoorians Motion for Summary Judgment. [Note 1]

A one-day trial was held on August 17, 2010. A stenographer was sworn to transcribe the testimony of Plaintiffs Richard Bazarian and Marilyn Bazarian, Jeffrey Gosdanian, the Bazarians neighbor, and Defendant Pamela Khachadoorian. Seventeen exhibits, some with multiple parts, and a diagram used as a chalk with notations made thereon at trial, were admitted in evidence. [Note 2] Only the Khachadoorians filed a post-trial brief, which was received by the court on November 1, 2010.

Based on all of the evidence and the reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, and in light of the arguments made by counsel, this court finds the following material facts:

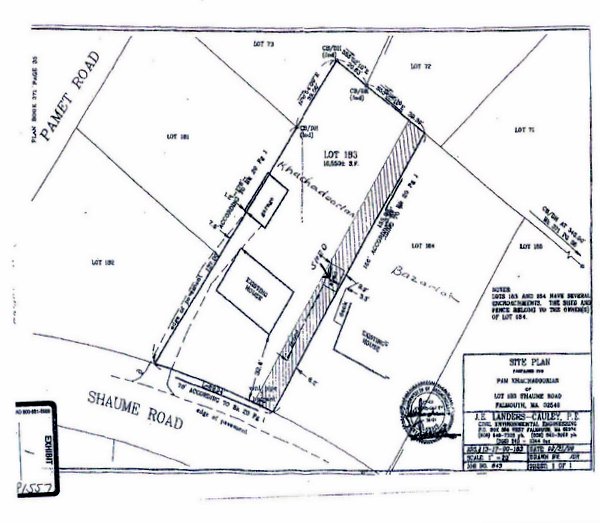

1. On July 14, 1971, the Bazarians purchased 10 Shaume Road, Falmouth, which is designated as Lot 184 on a plan of land prepared by Landers-Cauley (Landers-Cauley 99 Plan) dated September 21, 1999 (Lot 184 or Bazarians Property).

2. On November 18, 1997, the Khachadoorians purchased 6 Shaume Road, Falmouth, which is designated as Lot 183 on the Landers-Cauley 99 Plan (Lot 183 or Khachadoorians Property).

3. Between 1971, when the Bazarians purchased Lot 184, and 1997, when the Khachadoorians purchased Lot 183, title to Lot 183 was held in the names of Francis H. Kavanaugh, until his death, and Yuckie May C. Kavanaugh.

4. Lots 183 and 184 share a common boundary, which is the western boundary of Lot 184 and the eastern boundary of Lot 183.

5. As shown on Exhibit 1, the land claimed by Plaintiffs is a strip of land located along the easterly boundary of Lot 183. Forming a rectangle, it is approximately 10 feet wide, extends from Shaume Road to the rear lot line of Lot 183 for a distance of approximately 156 feet, and runs parallel to the boundary line separating the Bazarians and Khachadoorians properties (Disputed Area). Attached hereto is Sketch A which is a copy of Exhibit 1, on which the Disputed Area is cross-hatched.

6. When the Bazarians purchased Lot 184, it was undeveloped and covered by brush and trees. Before the Bazarians had their residence constructed on Lot 184, they cleared trees and undergrowth from their lot and the Disputed Area.

7. By 1972, a residence was constructed on the Bazarians Property. From 1972 until the date of trial, the Bazarians used the residence on Lot 184 as a summer home. They spent the months of June and July and weekends during the fall and spring there.

8. In 1974, the Bazarians constructed an 8x10 wooden shed within the Disputed Area. The shed was located approximately halfway between the front and rear lot lines of the Khachadoorians Property, as shown on Sketch A.

9. In 1976, the Bazarians constructed a stockade wooden fence in the Disputed Area. The fence was comprised of two portions. [Note 3] The front portion began in the section of Lot 183 between Shaume Road and the shed and extended to the front western corner of the shed (front portion). See Exhibit B. The rear portion extended approximately thirty (30) feet from the rear western corner of the shed toward, but not extending to, the rear lot line (rear portion). The fence was replaced on one occasion between 1976 and 2005, at which time there was no fence dividing the properties for period of weeks.

10. In the late 1970s or early 1980s, Mrs. Bazarian began cultivating and planting the Disputed Area, slowly working from the portion of the Disputed Area adjacent to Shaume Road toward the rear of the property. The cultivation of the Disputed Area included planting, fertilizing and watering the flowers (mostly day lilies), and trimming bushes and trees. It took Marilyn Bazarian until the early 1990s to reach the rear of the Disputed Area.

11. After purchasing Lot 183 in 1997, the Khachadoorians planted grass along the side of the stockade fence closest to the Khachadoorians residence and gardened in the portion of the Disputed Area adjacent to Shaume Road. Mrs. Khachadoorian never saw Mrs. Bazarian working within the Disputed Area.

12. As shown on Exhibit B, on which Mrs. Bazarian drew a yellow circle, as of 1997, when the Khachadoorians purchased their property, the only evidence of occupation by the Bazarians within the Disputed Area other than the shed and fence was a gravel walkway from the 6.2 mark on the Exhibit to the shed. There was nothing within the Circled Area in 1997 that required upkeep on a regular basis. Since purchasing their property, the Khachadoorians have made changes within the Circled Area as shown on Exhibit B, including planting shrubs, bushes, and flowering plants in the area along the side of the fence facing their house.

13. The portion of the Disputed Area from the shed to the back lot line slopes down, making it difficult to walk. In 1997, the area contained many trees, some of which remain there, as well as brush, thick vines around the trees, and dead branches and leaves. With the exception of the maintenance of the rear portion of the fence, the Bazarians acts of dominion with respect to the area between the shed and the rear lot line of the Khachadoorian Property were minimal and did not rise to the level of openness and notoriousness that is required to divest someone of record title.

14. Pamela Khachadoorian spoke to Richard Bazarian about the boundary issue twice during the late 1990s. The first conversation was in 1998, at which time she told him that the shed and fence were on her property, which he disputed. Pamela Khachadoorian then had the Landers-Cauley 99 Plan prepared and had concrete markers put in place to mark the record boundary line between the properties. In the second conversation, which occurred around September 1999, Pamela Khachadoorian gave Richard Bazarian a copy of the Landers-Cauley 99 Plan and said, [c]learly, your shed and fence is [sic] on my property.

15. In July of 2005, Richard Bazarian sought a special permit from the Falmouth Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) to construct an addition to the rear of his house. On September 14, 2005, a hearing was conducted by the ZBA on his application for a special permit. Richard Bazarian and Pamela Khachadoorian were both in attendance.

16. At the ZBA hearing, Pamela Khachadoorian requested that the ZBA grant Richard Bazarians application only on the condition that he remove the shed and fence from the Disputed Area because it was on her property. All parties understood that Pamela Khachadoorians opposition to the special permit was based on the Khachadoorians belief that the shed and fence were on their land. One of the ZBA members stated at the hearing that it was the intent of the ZBA to try and bring all of the boundary lines in the area into compliance because there were problems with the lots lines up and down the street.

17. When asked by a ZBA member whether he would be willing to take the fence and shed down, Mr. Bazarian responded Im concerned about the driveway and garage on that side. It would be 3 from my bedroom. I may need counsel for this.

18. The ZBA conditionally granted Richard Bazarians application. Two of the conditions were that 1) he remove the shed and fence from the Disputed Area and 2) file a revised plot plan indicating that such removal had been completed.

19. Richard Bazarian consulted with an attorney, and understood that he had the right to appeal the ZBAs decision. He also understood that the special permit required him to remove the shed and fence located on the Disputed Area if he wished to construct the addition to his home. The reason Richard Bazarian did not appeal the ZBA decision was to avoid a prolonged appeal process and expedite the completion of the addition he and his wife were anxious to complete by the summer of 2006.

20. The Khachadoorians did not appeal the grant of the special permit because the ZBA specifically conditioned its issuance on the removal of the shed and fence from the Disputed Area on the Khachadoorians Property. If the ZBA had granted Richard Bazarians permit request without the conditions regarding removal of the shed and fence, the Khachadoorians would have appealed the decision.

21. The shed and fence were removed at some time prior to Thanksgiving of 2005.

22. After the ZBA granted the special permit, the Bazarians decided to revise their original plans for the addition, and build it on the east side of their house instead of the rear. Because of these revisions, Mr. Bazarian applied for a second special permit.

23. On January 25, 2006, a hearing was held on Richard Bazarians second special permit application. He told the ZBA that the shed and fence had been removed. He did not indicate to them that he was still claiming title to the Disputed Area.

24. Pamela Khachadoorian did not attend the January 25, 2006 hearing because Mr. Bazarian had already removed the shed and fence from the Disputed Area and she was satisfied with their removal.

25. The ZBA granted the second special permit application with conditions, one of which was the submittal of a site plan confirming that the shed and fence had been removed. A plot plan, revised January 27, 2006, titled Site Plan Prepared for Richard Bazarian of Lot 184 Shaume Road Falmouth, MA by J.E. Landers-Cauley, P.E., was submitted after the hearing and depicted the removal of the encroachments.

* * * * * * * * * *

It is well settled that to establish title by adverse possession to land owned of record by another, a claimant must show proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, notorious, exclusive and adverse for twenty years. Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003) (quoting Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964)). The burden of proof rests entirely on the person claiming title and extends to all of the necessary elements of such possession. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421 (quoting Mendoca v. Cities Serv. Oil Co. of Pa., 354 Mass. 323 , 326 (1968)) (internal quotation marks omitted). If any of these elements is left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Mendoca, 354 Mass. at 326. Determin[ing] whether a set of activities is sufficient to support a claim of adverse possession is inherently fact-specific. Sea Pines Condominium III Assn v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 848 (2004).

The nature and extent of use required to establish title by adverse possession varies with the character of the land, the purposes for which it is adapted, and the uses to which it has been put. LaChance v. First Natl. Bank & Trust Co. of Greenfield, 301 Mass. 488 , 490 (1938); see also Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556 (1993) (As to actual use, [a] judge must examine the nature of the occupancy in relation to the character of the land.) (quoting Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992)). The claimant must demonstrate that he or she made changes upon the land that constitute such a control and dominion over the premises as to be readily considered acts similar to those which are usually and ordinarily associated with ownership. Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556 (quoting LaChance, 301 Mass. at 491 (1938)) (internal quotation marks omitted). Permanent improvements made upon the land are strong evidence of adverse possession, and are likely to satisfy each of its elements. LaChance, 301 Mass. at 490-91 (holding claimant who removed old fence and built hen coop and stone wall established title to disputed land by adverse possession); contra Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556-57 (holding elements of adverse possession not satisfied where claimant did not make any permanent improvements on land).

Acts of ownership must be open and notorious so as to place the true owner on notice of the hostile activity of the possession so that he, the owner, may have an opportunity to take steps to vindicate his rights by legal action. Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003) (quoting Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959)) (internal quotation marks omitted). To be open, the use must be without attempted concealment, Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007), and [t]o be notorious it must be known to some who might reasonably be expected to communicate their knowledge to the owner if he maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over his premises. It is not necessary that the use be actually known to the owner for it to meet the test of being notorious. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 420 (quoting 2 AMERICAN LAW OF PROPERTY § 8.56 (Casner ed. 1952)). If the use is open and notorious, it is deemed to place the true owner on constructive notice of such use, and it is immaterial whether or not the true owner actually learns of that use . . . . Id. at 422.

Open and notorious use, however, must be continuous. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624 (1992) (stating that infrequent use does not satisfy a claim for adverse possession). Acts of possession that are few, intermittent and equivocal are insufficient to serve as a basis for adverse possession. Kendall, 413 Mass. at 624 (quoting Parker v. Parker, 83 Mass. (1 Allen) 245, 247 (1861)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

To succeed on the element of exclusivity, the claimants possession of the area in dispute must be to the exclusion of the true owner. Even if a claimant non-permissively occupies the area to which he claims title in a manner that is actual, open, and notorious, unless he excludes others from the area in the manner that the true owner would, he does not satisfy the element of exclusivity. See Labounty v. Vickers, 352 Mass. 337 , 349 (1967); Bellis v. Bellis, 122 Mass. 414 (1877) ([T]he possession must be exclusive; and, if the true owner is in actual occupation of a part of the land described in the deed, the disseisin of the person entering will not extend to that part.).

The Bazarians purchased their property in 1971 and constructed the shed in 1974. There is no dispute that since 1974 the shed existed continuously until it was taken down by the Bazarians in 2005 as a condition of receiving the first special permit from the ZBA. Three witnesses, Mr. and Mrs. Bazarian and Jeffrey Gosdanian, testified to the sheds existence in the Disputed Area for more than the requisite twenty-year period and Mrs. Khachadoorian testified that when she and her husband purchased their property in 1997 there was a shed in the Disputed Area that was not removed until 2005. Therefore, the testimony clearly establishes that the shed existed from 1974 through 2005, well beyond the required twenty years. The sheds existence also satisfies the remaining elements of adverse possession, that such non-permissive use was open, notorious, adverse, and exclusive. Therefore, all of the elements for adverse possession are satisfied to establish that the Bazarians have adversely possessed the land beneath the shed.

In approximately 1976 the Bazarians constructed a fence along what they thought was the boundary line between their property and the Khachadorians Property. This fence was replaced on one occasion between 1976 to 2005 and when replaced, the fence was located along the same line as the previous fence, so the continuity of the twenty years was not broken by the replacement of the first fence with the second. The Bazarians removed the rear portion of the fence in 1998 when the Khachadoorians asked Mr. Bazarian if he could remove it in order to allow equipment onto the Khachadoorians property so they could install a new septic system. Only portions of the rear fence were reconstructed by Mr. Bazarian and the evidence did not establish that the rear portion of the fence was reconstructed along the same line as the previous fence.

The testimony from Mr. and Mrs. Bazarian and Mrs. Khachadoorian at trial established that the fence continuously existed for the required twenty year period with the front portion existing until 2005, and the rear portion of the fence existing until 1998. While Mr. Gosdanian, neighbor to the Bazarians, testified he did not remember a fence in the Disputed Area he also stated he didnt pay attention to it. To the extent his testimony puts in question whether the fence existed for more than twenty years, the greater weight of the evidence, including photographic evidence depicting a fence in the front portion of the Disputed Area during the requisite time period (1976 through 2005) and the testimony of the Bazarians and Mrs. Khachadoorian, establish the existence of both the front and rear portions of the fence for the requisite period. This fact alone, however, does not establish that the Bazarians have gained title to the portion of the Khachadoorians Property that is east of the fence.

While the maintenance of the fence constitutes a non-permisive use that was open, notorious, continuous, adverse, and exclusive for twenty years, the Plaintiffs also must prove they adversely possessed the area on the easterly side in order to establish adverse possession of that portion of the Disputed Area. This is so because the fence was not part of a fencing system that fully enclosed the Bazarians Property, excluding the true owner and everyone else other than the Bazarians and their invitees. In a situation such as the one presented here, where there is a single line of fencing, open at both ends, it is necessary for the parties asserting adverse possession to establish that they asserted control and dominion over the area on their neighbors property as well as the fence itself. It is not sufficient to establish the existence of the fence, which one could easily walk around. This is particularly so where, as here, the fence did not run the full length of the parties property line.

The Bazarians acts of dominion over the property adjacent to the fence is not enough to carry their burden of proof. The testimony establishes that beginning in the late 1970s or early 1980s, the Bazarians used the area closest to Shaume Road (Front Yard Area) by planting and maintaining various flowers and shrubs. The plantings described by Mrs. Bazarian, supported by some photographs, were not so obviously landscaped so as to put the Khachadoorians predecessors-in-title on notice that she was making a claim to that portion of their property.

As to the rear portion of the Disputed Area from the shed location toward the rear lot line (Rear Yard Area), the Bazarians did not establish their claim for two reasons. First, the testimony established that Mrs. Bazarians gardening activities within the Disputed Area began nearest the street, in the Front Yard Area sometime in the late 1970s or early 1980s, progressing toward the rear lot line during the early 1990s. As it is the burden of the Plaintiffs to prove each and every element of adverse possession, Plaintiffs were required to establish use during a period of at least twenty years in which Mrs. Bazarian planted in the Rear Yard Area. The court does not find that the use of the Rear Yard Area was continually maintained for twenty years. Second, the plants and bushes toward the rear of the Kachadorians Property were naturalized and not even as discernible as the plantings (mostly day lilies) within the Front Yard Area. This court does not find that they were sufficiently open and notorious to put the Kachadorians on notice that the Bazarians were claiming the Rear Yard Area and using it as their own.

Thus, based on the credible evidence of adverse possessory acts, the Bazarians proved only that they adversely possessed the area under which the shed was maintained. The Khachadoorians argue the Bazarians should be estopped from claiming they have acquired title to any portion of the Disputed Area, including the shed area. The elements establishing the defense of equitable estoppel are (1) [a] representation or conduct amounting to a representation intended to induce a course of conduct on the part of the person to whom the representation is made; (2) [a]n act or omission resulting from the representation, whether actual or by conduct, by the person to whom the representation is made; and (3) [d]etriment to such person as a consequence of the act or omission. Turnpike Motors, Inc. v. Newbury Group, Inc., 413 Mass. 119 , 123 (1992) (quoting Cleaveland v. Malden Sav. Bank, 291 Mass. 295 , 297-98 (1935).

The Khachadoorians contend the Bazarians are estopped from asserting title to the Disputed Area because Mr. Bazarian removed the fence and shed as he had to do in order to receive the benefits of the special permits the ZBA issued and he removed them knowing that the Khachadoorians believed the structures were located on their property. The Khachadoorians believed such removal was a relinquishment of the Bazarians claim to the entire Disputed Area, and in reliance on such conduct, did not appeal the ZBAs decision. They allege that long after the twenty-day appeal period expired, Mr. Bazarian represented to Mrs. Khachadoorian that despite the removal of the encroachments, he was not relinquishing any rights he and his wife had to the Disputed Area. The Kachadorians argue that had they known the Bazarians still claimed title to the Disputed Area, they would have appealed the grants of the special permits.

The Bazarians, on the other hand, argue that after removal of the shed and fence they continued to maintain the Disputed Area, and informed the Khachadoorians of their non-relinquishment of title before the application for the second special permit was filed. The principal issue in the estoppel defense concerns whether the Khachadoorians were timely informed of the Bazarians position that they has not relinquished (or acquiesced to the relinquishment of) their claim of title to the Disputed Area. The Bazarians contend the conversation between Mr. Bazarian and Mrs. Khachadoorian took place in approximately December of 2005, at which time Mr. Bazarian stated, Im just taking this fence and shed down, but Im not relinquishing my title to this land. I dont intend to. The Khachadoorians, on the other hand, argue that the conversation did not occur until April 2008, when Mrs. Khachadoorian informed Mr. Bazarian that she and her husband would be constructing a wall comprised of railway ties approximately a foot from the boundary line and Mr. Bazarian responded by stating he had not relinquished any rights to the Disputed Area by removing the fence and shed as a condition of the second special permit. To the extent the testimony on this point varies, I credit Mrs. Khachadoorians testimony that the conversation took place in 2008. [Note 4]

While it is true that an appeal of the special permit would have been limited to the issue of the proposed addition, and the ZBA had no authority to determine title as between the abutting landowners, nonetheless it appears to this court that the Bazarians should not now be allowed to pursue this action after receiving the benefits of the ZBAs special permit decisions. It was clear in both ZBA hearings and the resultant decisions that the ZBA relied on the Bazarians compliance with the condition that the encroachments be removed and would not have granted the relief sought but for compliance with that condition due to the Khachadoorians opposition and the fact that the shed and fence actually encroached onto their property.

Judgment to issue accordingly.

RICHARD BAZARIAN and MARILYN BAZARIAN v. RONALD H. KHACHADOORIAN and PAMELA KHACHADOORIAN

RICHARD BAZARIAN and MARILYN BAZARIAN v. RONALD H. KHACHADOORIAN and PAMELA KHACHADOORIAN