PAUL DENADAL and CECILE DENADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

PAUL DENADAL and CECILE DENADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

MISC 07-356049

May 21, 2012

BRISTOL, ss.

Long, J.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON DEFENDANTS' MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION

Introduction

This case (the second between the DeNadals and the Beauregards, and the third overall) concerns a 40-wide private way off Pettey Lane in Westport and the parties respective rights in that way. [Note 1] Judgment entered on August 1, 2011, declaring: (1) the parties may park in the 10-wide section of the 40 way immediately abutting their properties, [Note 2] (2) the parties may put objects or barriers in those 10 sections (i.e. where they own the fee), so long as those objects and barriers are easily removable and immediately removed when that 10 is reasonably necessary for access or egress to the other properties on the way, (3) no one other than the party that owns the underlying fee in that section of the way (or their invitees) may park there, (4) the center 20 of the way must be kept open and unobstructed at all times, (5) any party having rights in the way wishing to relocate any section of the current paving to the center 20 may do so, so long as they bear the full expense of such relocation (i.e. ensuring that the center pavement is 20 wide and merges easily and seamlessly with the other sections of the paved way; otherwise they must bear the expense of making it so, potentially including the cost of re-locating and re-paving the full length of the way if that is necessary to make its merger easy and seamless), and (6) in the meantime, the current paving must remain in its present location. All of the parties other claims were dismissed, with prejudice.

By motion filed September 2, 2011, the defendants sought reconsideration of one aspect of that Judgment, but only with respect to the plaintiffs (the DeNadals), not themselves. This was its ruling that the parties could put objects or barriers in the 10 section of the way immediately abutting their properties so long as those objects and barriers (parked cars, for example) were easily removable and immediately removed when that 10 was reasonably necessary for access or egress to the other properties on the way. The defendants have no problem with that aspect of the Judgment as it applies to themselves. Both the Beauregards and Ms. Penman want the right to park in the 10 section of the way in front of their homes. Indeed, the Beauregards regularly park several vehicles in their 10 section of the way, and have no objection to their neighbors immediately across the way doing the same in that neighbors 10. [Note 3] What the defendants seek, and all that they seek, is a modification of the Judgment so that it prohibits the DeNadals from enjoying that same right, i.e. a ruling that the 10 section in front of the DeNadals property, and that section alone, plus the 20 in the center of the way, be kept free and unobstructed at all times.

The defendants make two arguments in support of their motion. The first is their contention that the full 40 width along the entire length of the way must remain open and unobstructed at all times as a matter of law (a position inconsistent with their insistence on their right to park in their 10 section of the way). The second is their fact-dependent claim that the 10 in front of the DeNadal property is reasonably necessary for them to access and exit their homes.

The DeNadals make four arguments in response. First, that the motion (filed over a month after Judgment was entered) was untimely under Mass. R. Civ. P. 59(e) (A motion to alter or amend the judgment shall be served not later than 10 days after entry of the judgment.). Second, that if considered a Rule 60(b) motion, it fails because Rule 60 does not provide for general reconsideration of an order or a judgment, nor does it provide an avenue for challenging supposed legal errors, nor for obtaining relief from errors which are readily correctible on appeal. Pentucket Manor Chronic Hospital Inc. v. Rate Setting Commn, 394 Mass. 233 , 236 (1985) (internal citations omitted). Third, on the merits, that this is not the type of easement that must remain open and obstructed for its entire width, along its entire length, always (i.e., it is not an easement whose limits and boundaries are defined, all of which is appropriated and set apart for this use, see Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 189 (1957) (internal citations and quotations omitted)), but rather one where use may be made by the servient landowners so long as that use does not interfere unreasonably with the easement holders ability to ingress and egress (see Cannata v. Berkshire Natural Resources Council Inc., 73 Mass. App. Ct. 789 , 797 (2009); Brassard v. Flynn, 352 Mass. 185 , 189 (1967)). [Note 4] Fourth, as a factual matter, that any asserted need by the defendants for the DeNadals 10 was either unsupported or, to the extent it existed, self-inflicted by the defendants own use for parking of their own 10 and thus not reasonably necessary.

An evidentiary hearing was held on the merits of the defendants motion, reserving ruling on the issue of its timeliness. Notice of Docket Entry (Oct. 18, 2011). Based upon the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at that hearing and the earlier trial of this matter, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I agree with each of the plaintiffs contentions. The defendants motion is thus DENIED.

The Defendants Motion is Untimely

Defendants motion seeks reconsideration of a portion of the courts August 1, 2011 Judgment. Mass. R. Civ. P. 59(e) requires motions for reconsideration to be served not later than 10 days after entry of the judgment. Judgment was entered August 1, 2011. Defendants motion was served September 2 almost three weeks late, and thus time-barred. Because the motion affects the finality of judgment and tolls the time for taking an appeal, the 10-day limit may not be enlarged by the court. [Mass. R. Civ. P.] Rule 6(b). Reporters Notes to Rule 59.

The defendants argue that their motion should not be time-barred because the Beauregards did not receive notice of the Judgment until August 18. [Note 5] There are two problems with this. First, [t]he 10-day period, it should be emphasized, begins to run from the date of effective entry of judgment under Rule 58. This provision applies even though a party has not received notice of the judgment under Rule 77(d) from the clerk or adverse party; or even if the clerk fails to record a correct copy of the judgment as required by Rule 79(b). Reporters Notes to Rule 59. Second, if, in fact, the Beauregards did not receive actual notice until August 18, it is entirely their own fault. A copy of the Judgment and the Decision on which that Judgment was based were mailed to all trial counsel, including the Beauregards, on August 1. The Beauregards trial counsel was Timour Zoubaidoulline Esq., and the mailing for the Beauregards was thus made to him. It was sent to attorney Zoubaidoullines office address on file with the Massachusetts Board of Bar Overseers, and it was his responsibility to keep that address up-to-date and himself current with the mailings to that address. [Note 6] The Beauregards argument that attorney Zoubaidoulline had effectively withdrawn from their representation when he left Mr. Beauregards law firm has no merit. Attorney Zoubaidoulline had not filed a motion to withdraw or even a notice seeking to withdraw prior to the time of the courts mailing. Indeed, he has not done so since and remains the Beauregards counsel of record in these proceedings.

The Defendants Motion Does Not Fall Within Rule 60

The defendants motion is candidly (and correctly) styled as one for reconsideration. As such, it does not fall within Mass. R. Civ. P. 60 (which has longer deadlines than Rule 59), and the relief it seeks cannot be granted under that rule. The motion is not based on an alleged clerical mistake in the judgment arising from oversight or omission. Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(a). It is not based on mistake, inadvertence, surprise, or excusable neglect, Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1); newly discovered evidence which by due diligence could not have been discovered in time to move for a new trial under Rule 59(b), Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2), or fraud,

misrepresentation, or other misconduct by an adverse party, Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(3). It does not contend, nor is there a basis to contend, that the judgment is void. Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(4). It does not argue, nor is there a basis to argue, that the judgment has been satisfied, released, or discharged, or a prior judgment upon which it is based has been reversed or otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judgment should have prospective application. Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5). Lastly, its grounds do not bring it within the narrow category of any other reason justifying relief from the operation of the judgment, Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(6). Pentucket Manor Chronic Hospital Inc. v. Rate Setting Commn, 394 Mass. 233 , 236 (1985) (internal citations omitted) (Rule 60 does not provide for general reconsideration of an order or a judgment, nor does it provide an avenue for challenging supposed legal errors, nor for obtaining relief from errors which are readily correctible on appeal.). See also J. W. Smith & H. B. Zobel, 7 Mass. Practice (Rules Practice), Second Ed., §60.15 at 389-391 (2011-2012 Pocket Part) and cases cited therein (Although [Rule 60(b)(6) has been applied in a gamut of situations, it possesses, in fact an extremely meager scope, and relief requires extraordinary or compelling circumstances

.The rule is not a substitute for appeal, and it is not a device to force the trial judges reconsideration of a litigants earlier defeat, nor does it afford a vehicle for allowing modification of a consent judgment or for permitting a party to raise a previously overlooked legal argument

Rule 60 does not provide for the trial courts general reconsideration of an order or a judgment; nor is it an avenue for challenging supposed legal errors, or for obtaining relief from errors readily correctable on appeal. Changes in the law, standing alone, do not justify vacating a judgment, particularly if the movant has failed to appeal.).

The Defendants Motion Also Fails on its Merits

Given the untimeliness of the defendants motion, I need not discuss its merits. I do so, however, for the sake of completeness. As previously noted, their arguments are twofold: first, that the full width of the 40-wide easement must remain open and unobstructed as a matter of law, not just where and when reasonably needed for access and egress, and second, that the section in front of the DeNadals property is reasonably needed by the defendants for that purpose. Neither of those arguments withstands scrutiny.

To begin with, the easement at issue is not one that must remain open and unobstructed across its entire 40 width as a matter of law, i.e., an easement whose limits and boundaries are defined, all of which is appropriated and set apart for this use. Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 189 (1957) (internal citations and quotations omitted)). [Note 7] Rather, it is one where use may be made by the servient landowners so long as that use does not interfere unreasonably with the easement holders ability to ingress and egress. See Cannata v. Berkshire Natural Resources Council Inc., 73 Mass. App. Ct. 789 , 797 (2009); Brassard v. Flynn, 352 Mass. 185 , 189 (1967). The Beauregards themselves recognized this when they asserted a right to park in the way, everywhere along its length, in their previous action regarding this easement (a recognition that a portion of the easements width could be blocked on a continuing basis without impairing the easement holders access rights), [Note 8] and they are judicially estopped from changing that position now. See Otis v. Arbella Mutual Ins. Co., 443 Mass. 634 , 639-640 (2005) (Judicial estoppel is an equitable doctrine that precludes a party from asserting a position in one legal proceeding that is contrary to a position it had previously asserted in another proceeding.). Moreover, as previously noted, their argument that the entire 40 width cannot be obstructed by anything at any time, regardless of whether the portion in question is reasonably needed for access and egress, is completely inconsistent with their own practice of parking in the 40 way in front of their property and of having no objection to their neighbors across the way doing the same. [Note 9] Most importantly, this issue is res judicata between the Beauregards and the DeNadals as a result of the judgment in Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, 14 LCR 581 (2006), affd 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2008). As that judgment stated:

[T]he [Beauregards] have the right to pass and repass over the portion of the 40 way owned by the DeNadals for the purpose of ingress and egress to the [Beauregards] home, and for no other purpose; [the Beauregards] have no right to park on any part of the 40 way owned by the DeNadals; and the DeNadals have the right to use their portion of the 40 way in any way that does not impair the Beauregards right of ingress or egress.

Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, Land Court Case No. 05 Misc. 316714 (KCL), Final Judgment (Oct. 3, 2006) (emphasis added).

The ultimate issue is thus whether the 10 portion of the way in front of the DeNadals property is reasonably necessary for the defendants to access and egress their property. Having heard the testimony and considered the exhibits offered at the evidentiary hearing, I find that it is not. To the extent either Ms. Penman or the Beauregards are experiencing any difficulty coming or going, it is entirely due to their own actions specifically, their practice of parking in the 10 of the way in front of their own properties. If they did not park there, or if they simply troubled to move those cars when they wanted additional turning space, [Note 10] they would have no difficulty whatsoever. Thirty feet of space (the 20 in the center of the way, plus the 10 in front of their own property) is more than sufficient to come, go, and turn around. Indeed, the twenty feet in the center is sufficient. [Note 11] Nothing more is reasonably necessary and, at most, all that is required is an extra maneuver often just the classic three-point turn. [Note 12] If there is the rare, true need for more than the 20 in the center (e.g. a moving van, a large construction vehicle, or the like) the Judgment in this case already provides for that situation. As it directs, only easily removable objects and barriers may be placed in the 10, and those objects and barriers must immediately be removed when that 10 is reasonably necessary for access or egress to the other properties along the way. Judgment (Aug. 1, 2011).

In short, the defendants (really, the Beauregards) motion is motivated not by need but by spite, evidenced by the fact that they wish to deny the plaintiffs and no one else the very right they insist upon for themselves the right to use the 10 portion of the way in front of their properties. [Note 13] If there are issues between the Beauregards and the DeNadals and it is clear to me there are, whatever the reasons and whoevers fault those issues should be resolved elsewhere, not in these proceedings.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the defendants motion for reconsideration is DENIED.

SO ORDERED.

By the court (Long, J.)

Exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

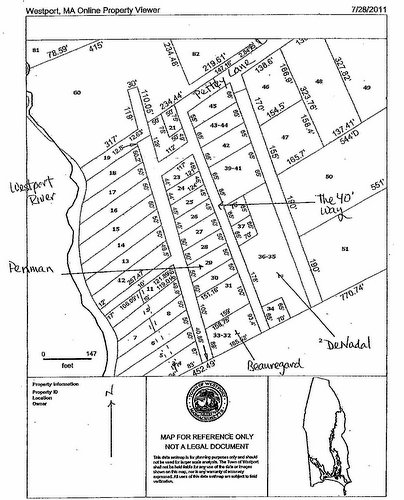

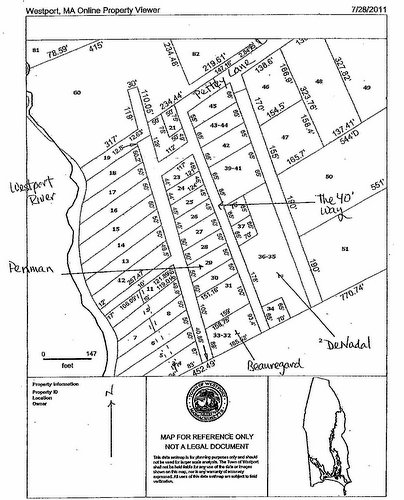

[Note 1] The previous case between them was Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, Land Ct. Case No. 05 Misc. 316714 (KCL), 14 LCR 581 (2006), affd, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 1107 (2008) (Memorandum and Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28. There was also yet earlier litigation regarding the way the consolidated cases of Murphy v. Tuckerman, Bristol Superior Court Civil Action No. 90-01557 and In re: Registration Petition of the Susan Tuckerman Trust, Land Court Reg. Case No. 42931, both decided by the late Land Court Chief Justice Robert Cauchon. Decision (Oct. 31, 1995) and Judgment (Oct. 31, 1995). The way, and the location of the parties properties along it, are shown on the attached Exhibit 1.

[Note 2] It was undisputed at trial that each of the parties owns the fee to the midpoint of the way in the section immediately abutting their property, i.e. 20 of the total 40 width. See G.L. c. 183, §58 (the derelict fee statute).

[Note 3] The neighbors so referenced are the owners of lot 34, directly across from the Beauregard property (lot 33-32). The DeNadal property is lot 36-35. See Ex. 1, attached.

[Note 4] This was the basis for my factual finding and ruling that the parties could each park on or otherwise use the 10 section of the way immediately abutting their properties, so long as what was put there was easily removable and immediately removed when that 10 was reasonably necessary for access or egress to the other properties on the way. See Decision at 9-11, 13 (Aug. 1, 2011).

[Note 5] According to Mr. Beauregard, this was the date when he received a copy of the Decision and Judgment from his co-defendant, Maria Penman. Affidavit of Philip Beauregard at 1 (Nov. 22, 2011). Ms. Penman does not dispute that her counsel received a copy of the August 1, 2011 Decision and Judgment shortly after they were mailed to counsel by the court on August 1.

[Note 6] Attorney Zoubaidoulline admits that copies of the August 1, 2011 Decision and Judgment were sent to his office in Medford (his address on file with the Board of Bar Overseers) and that, although he now lives and works primarily in the New York City metro area, he uses the Medford office for his Massachusetts-related matters. Affidavit of Timour Zoubaidoulline at 2 (Nov. 22, 2011). He claims he neither notified the Beauregards of the Decision and Judgment, nor sent them copies, or apparently even called them to discuss it, because he never thought they had not been notified of the Courts judgment. Id. He concedes that he was in the United States, presumably in regular contact with his Medford office, until August 19 when he began a three-week trip to Croatia and Russia. Id. at 3.

[Note 7] Delconte-type easements are instances where the grantor and grantee have precisely defined the boundaries of the easement granted and made clear that the entirety of the bounded area is necessary to fulfill its purpose. (Delconte, for example, involved a narrow passageway through sand dunes to a beach). This is most clear in Dickinson v. Whiting, 141 Mass. 414 , 417 (1886) where the right of way (for the purpose of driving cattle and teams) was a precise 25 wide, bounded by permanent stone walls on each side, with bar-ways at intervals opening into adjacent fields, extending from the highway to the river. As the court noted, to construe it as anything less would be to do injustice to the grantee who, having found a way such as that described in the deed, was able to determine, from its width and direction, when he closed the purchase, whether it was sufficient for his purposes

[A]nything erected therein which, for practical purposes, made its use less convenient and beneficial than before, was an obstruction which wrongfully interfered with the privilege to which he was entitled. Id. at 416-417. Accord, Gerrish v. Shattuck, 128 Mass. 571 , 574 (1880); Gray v. Kelley, 194 Mass. 533 , 534 (1907) (granting language specified that there was a right to pass and repass at pleasure over any part of said private way of twenty-four feet wide adjoining the premises conveyed.) (emphasis added). This easement has no such language, and is nothing of the kind.

[Note 8] Harrison-Beauregard v. DeNadal, Land Ct. Case No. 05 Misc. 316714 (KCL), Plaintiffs First Amended Complaint (May 19, 2006). The relief sought by the Beauregards in that case was a declaratory judgment that [the Beauregards] have the right to park on all parts of the private ways of Petteys Heights, so long as their (and others) parking does not obstruct other residents rights to travel and utilize said way for access to their parking. Id.at ¶15.

[Note 9] The way dead-ends at the Beauregards and their across-the-way neighbors property. See Exhibit 1, attached (their across-the-way neighbor is at lot 34). If there is an argument for keeping the full 40 width unobstructed anyplace on the way, surely it would be at that dead-end where those unaware it is not a through road would turn around.

[Note 10] As previously noted, the Beauregards regularly park several cars both immediately in front of their property and at the end of the way. To the extent they have difficulty getting those and their other cars in and out, this (plus the boat and car parked immediately across the way by the owner of lot 34) is the cause. See Evidentiary Hearing Exs. 6, 8 and 9.

[Note 11] The Beauregards contend that the neighborhood trash removal truck cannot get up and down the way if the DeNadals are permitted to park or otherwise block the 10 section of the way in front of the DeNadal property. This is not so. The trash truck backs down the way, as it does on all of the other dead-end ways in the subdivision, and then picks up trash from the homes along the way as it goes forward. Again, if the defendants are truly concerned, they could remove their own cars from the 10 of the way in front of their homes. Their insistence that the DeNadals do something that they themselves contend they do not have to do is telling.

[Note 12] The Beauregards main difficulties appear to take place when the 20 in the center is significantly narrowed either by their own vehicles or their across-the-way neighbors boat and cars.

See Evidentiary Hearing Exs. 6, 8 and 9.

[Note 13] Putting removable objects in the way is the functional equivalent of a parked car.

PAUL DENADAL and CECILE DENADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN

PAUL DENADAL and CECILE DENADAL v. PHILIP BEAUREGARD, KATHLEEN HARRISON-BEAUREGARD and MARIA PENMAN