In this case I am called upon to decide the location of a common boundary between neighbors in the Town of Acushnet, Bristol County, Massachusetts. Plaintiffs Bryant and Judith Bernier ("Berniers" or "Plaintiffs"), the record title holders of a certain parcel of unimproved land off Hathaway Road in Acushnet, claim as part of their title parcels of land ("Disputed Areas") more fully described below. Defendants Norman and Maria Fredette, David Bechtold, and Stanley and Kathryn Chaberek [Note 1] have disputed placement of the common boundary in the position asserted by Plaintiffs. The Defendants have taken the position that, with the common boundary located where the Defendants say it belongs, the Disputed Areas are not part of Plaintiffs' property. Plaintiffs seek injunctive and monetary relief against the Defendants for their claimed trespass onto the Disputed Areas. Defendants deny having trespassed on Plaintiffs' property and, in the alternative, argue that Plaintiffs have failed to prove any actual damage resulting from any such trespass.

The Plaintiffs filed their complaint on August 4, 2008 pursuant to G. L. c. 240, §§ 6 - 10, (and also seek declaratory judgment) to remove a cloud on Plaintiffs' title that they say exists as a result of claims to title made, and actions taken, on and with respect to the Disputed Areas by the Defendants. [Note 2]

Defendant Chaberek appeared in this action and defended. Subsequently, Chaberek executed and delivered to the court an agreement for judgment which was accepted by the Court on July 12, 2010. The case proceeded to trial on the claims of the remaining defendant parties, requiring the court to determine the record title to only the portions of the Disputed Areas claimed by defendants Fredette and Bechtold (collectively "Defendants").

On August 8, 2008, Plaintiffs filed a motion for preliminary injunction and moved for a judicial endorsement of their memorandum of lis pendens. On September 3, 2008, Defendant Bechtold filed a special motion to dismiss under G. L. c. 184, § 15(c)). I held a hearing on September 4, 2008, in which I allowed the motion for preliminary injunction in part as to those activities that had the potential to result in permanent alteration of the Disputed Areas. I gave the parties twenty days to file a stipulation in lieu of preliminary injunction or alternatively, to submit competing proposed forms of injunction. At the same hearing, I allowed the motion for endorsement of a memorandum of lis pendens on the condition that Plaintiffs amend their verified complaint to be compliant with the statutory language. Finally, I denied Defendant Bechtold's special motion to dismiss, without prejudice to bringing on a motion for summary judgment resting on the same or similar issues. On September 9, 2008, Plaintiffs filed their amended verified complaint and on September 29, 2008 I endorsed Plaintiffs' memorandum of lis pendens.

On July 9, 2010, after the completion of discovery and before trial, in the presence of counsel, a number of the parties, and their representatives, including surveyors involved in this case, I took an extensive view of the Disputed Areas and the surrounding land. There were four days of trial at which evidence was taken. I received post-trial briefs and requests for findings and rulings and then gave counsel the opportunity to argue the case on the record. I now decide the case.

On all the testimony, exhibits, stipulations, and other evidence properly introduced at trial or otherwise before me, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, and taking into account the pleadings, and the memoranda and argument of the parties, I find the following facts and rule as follows:

Findings of Facts

1. Plaintiffs Bryant and Judith Bernier ("Berniers") are individuals who reside at 186 Hathaway Road, Acushnet. The Berniers hold record title to a certain parcel of unimproved land ("Lot 13") off Hathaway Road described as parcel one in a deed recorded in the Bristol County (South District) Registry of Deeds ("Registry") in Book 4295, Page 299.

2. Defendants Norman and Maria Fredette ("Fredettes") are individuals who reside at 16 Rene Street in Acushnet, and are record title holders of certain property ("Lot 16") described in a deed recorded in the Registry in Book 5503, Page 254.

3. The Fredettes dispute the location of their common boundary with the Berniers. The area resulting from this disagreement ("Fredette Disputed Area") contains approximately 31,119 square feet of the overall Disputed Areas.

4. Defendant David Bechtold ("Bechtold") is an individual who resides at 17 Rene Street in Acushnet, and is record title holder of certain property ("Lot 16A") described in a deed recorded in the Registry in Book 4484, Page 282.

5. Bechtold disputes the location of his common boundary with the Berniers. The area resulting from this disagreement ("Bechtold Disputed Area"), contains approximately 3,853 square feet of the overall Disputed Areas.

6. Defendants Stanley and Kathryn Chaberek ("Chabereks") are individuals who reside at 23 Rene Street and are record title holders of certain property ("Lot 16D") described in a deed recorded in the Registry in Book 8431, Page 26.

7. Samuel Wing (born 1794) was the common owner of a large tract of land that included contemporary Lots 16, 16A, 16D, 13, 8 and 7 (together the "Wing Estate"). See FRANKLIN HOWLAND, A HISTORY OF THE TOWN OF ACUSHNET, 380 (1907). Samuel Wing's descendants carved up the Wing Estate by sequential conveyances in the late nineteenth century. The first lot conveyed out of the Wing Estate was Lot 7 by deed to Elijah Bates on May 10, 1870. [Note 3] On May 13, 1870, Levi Wing simultaneously conveyed two lots: Lot 16 by deed to Samuel B. Hamlin [Note 4] and Lot 20, a lot separate from the Wing Estate, by deed to George L. Russell. [Note 5] The third lot conveyed out of the Wing Estate was Lot 8, conveyed by Levi's son Samuel Wing by deed to Anna Bradford on January 4, 1899. [Note 6] The next day, January 5, 1899, Bradford, in consideration of one dollar, conveyed Lot 13 by deed back to Samuel. [Note 7]

8. The May 10, 1870 deed of Lot 16 ("Lot 16 Deed") provides the following lot description:

...[B]eginning at a stake in a pine stump, thence east four and one fourth degrees north, forty 32/100 rods to a stake and stones in the line of Silas H Collins land, thence south one and one half degrees west, eighty 40/100 rods to a stake and stones, thence west four and three fourth degrees south, twenty six 1/2 rods to a stake and stones, thence north ten and one half degrees east, twenty nine 80/100 rods to a stake and stones the northeast corner of Edward G. Dillingham's land, thence north seventeen degrees west, fifty three and one half rods to the first mentioned bound...

(By "Lot 16" I refer in this decision to the property as described in this deed, not to contemporary lot 16, which is a subdivided portion, along with Lots 16A and 16D, of the former Lot 16 established in the Lot 16 Deed. The boundaries of Lot 16 as created in the nineteenth century, and particularly Lot 16's boundary with Lot 13, lie at the center of the parties' dispute now before me.)

Summary of Arguments.

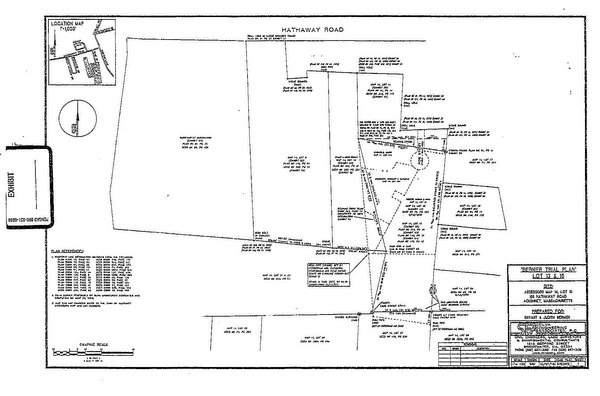

Plaintiffs begin by insisting that Lot 16, as the undisputed senior parcel to Lot 13, first should be placed on the ground in its entirety in accordance with the Lot 16 Deed. Plaintiffs assert that, based on deed and plan research and field surveying work, the location of Lot 16 is as shown on the "Bernier Trial Plan," attached to this decision as an exhibit. [Note 8] The common boundary, Plaintiffs argue, has been established for more than 140 years and is supported by deeds of record from 1870, found monuments, and plans of record.

The Plaintiffs attack the Defendants' placement Lot 16's western boundary by asserting, first, that the Lot 16 Deed contains a "scrivener's error" in the call for the lot's northern boundary and, second, that the survey on which Defendants relied to subdivide Lot 16 mistakenly calculated the interior angles of the lot based on the uncorrected "scrivener's error," thereby including in Defendants' subdivided lots more property than they held title to along the western boundary of Lot 16. Plaintiffs also contend that the techniques employed by Defendants' expert in placing Lot 16's western boundary are inconsistent with traditional and accepted surveying practice and surrounding property boundaries.

The Defendants respond by arguing that the "constellation" of monuments called for in the Lot 16 Deed, and asserted to have been found by their expert, dictate that the western boundary of Lot 16 overlaps the eastern boundary of Lot 13, creating the Disputed Areas. The Defendants insist that Lot 13, as the junior of the two lots, yields to Lot 16 and legal title to the overlapping Disputed Areas belongs to the Defendants, respectively. The Defendants' proposed placement of the disputed common boundary is depicted on "Chalk B." [Note 9]

The Defendants attack the Bernier Trial Plan by rejecting the Plaintiffs' assertion that the northern boundary of Lot 16 contains the transposed course error on which Plaintiffs rely. Rather, the Defendants claim that mistakes in the deeds to Lots 8 and 13 and in subsequent plans made in reliance on those flawed descriptions have resulted in those lots being essentially "shifted," over time, to the east, creating the Disputed Areas. As Lot 16 is senior in rights to Lot 13, Defendants claim title to the Disputed Areas. Defendants further allege that the analysis of surrounding property lines conducted by the Plaintiffs' experts was incomplete and inconsistent with standard surveying practice.

The common boundary of Lots 16 and 13 is as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan.

The location of a disputed boundary line is a question of fact to be determined "on all the evidence, including the various surveys and plans, and the actual occupation and use[s] by the parties ..." Hurlbert Rogers Mach. Co. v. Boston & Maine R.R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). Where, as here, deed construction is a part of that analysis, the law provides:

... a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Moreover, when abutter calls are used to describe property, the land of an adjoining property owner is considered to be a monument.

Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 680 (2004) (internal citations omitted). Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered. When a "monument cannot be

found and its location cannot be made certain by evidence," other descriptions control. Stoughton v. Schredni, 7 LCR 61 , 66 (1999). After monuments, it is next courses and distances which control. Morse v. Chase, 305 Mass. 504 , 507 (1948). All of these rules of construction, however, "are not to be followed if they would lead to a result plainly inconsistent with the intent of the parties." Id. Where the described courses of a surveyed parcel are erroneous and "it is possible to rearrange them to conform to the bounds and the adjoining owners as described by the previous and subsequent deeds so that the description fits with the surrounding parcels," it is proper to do so. Ellis v. Wingate, 338 Mass. 481 , 485 (1959). See also W. ROBILLARD AND D. WILSON, BROWN'S BOUNDARY CONTROL AND LEGAL PRINCIPLES, 340 (6TH ED. 2009)("BROWN") ("If a description of land contains an error or mistake, and if the error or mistake can be isolated, the error or mistake is placed where it occurs.").

To place the disputed common boundary on the ground correctly, it is necessary first to place Lot 16 on the ground in its entirety, honoring the intent of the parties who first created Lot 16. See Morse, 305 Mass. at 507.

The First Course. I begin with the first course ("First Course") in the description of the Lot 16 Deed constituting the northern boundary, which reads "...[B]eginning at a stake in a pine stump, thence east four and one fourth degrees north, forty 32/100 rods to a stake and stones in the line of Silas H Collins land...." Both parties agree that the monuments called for in this First Course have been found on the ground. The "stake in a pine stump" constituting the beginning point is, the parties stipulate, located at the northwest corner of Lot 16 on the Bernier Trial Plan. Both parties likewise agree that the "stake and stones in the line of Silas H. Collins land" is in the location of the northeast corner as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan. It is undisputed that the line established by two monuments has served as the northern boundary since 1870.

Assuming that the deed is written on a magnetic bearing basis, a controversy I address below, the First Course as written would overlap the southern boundary of Lot 14 [Note 10] and terminate at a point located within that lot. Plaintiffs attribute this inconsistency to a simple transposition error: the First Course was written wrong in the Lot 16 Deed, and despite the words used, actually was intended to read "thence east four and one fourth degrees south..." rather than "north." This "scrivener's error" theory is corroborated by the fact that, when followed as Plaintiffs' urge, the First Course coincides with both the found "stake and stones" at the northwest corner of Lot 16 and coincides within 2.875 degrees with the southerly boundary of Lot 14 as described in its deed (from "a stone and stump" in the "eastern line of land of Samuel Wing" ... "thence east seven and one eighth (7 1/8)[?] south...").

Defendants argue that the Lot 16 Deed is not in error but the found "stake and stones in the line of Silas H. Collins land" nonetheless control placement of the northern boundary. While Defendants correctly assert that "a call for natural or artificial monuments trumps a call for direction, distance or area," BROWN, 324-325, this certain principle does not preclude acceptance of Plaintiffs' "scrivener's error" theory. To the contrary, Plaintiffs' theory supports Defendant's argument that the monuments control. While the placement of the First Course is not in dispute, I conclude that the Lot 16 Deed contains a transposition error in the First Course that should be isolated where it occurs. BROWN, 340. As a result, the rest of the Lot 16 Deed should be construed as if the First Course did not contain the "scrivener's error" and instead called for a bearing of "east four and one fourth degrees south." The correction of this error alters the placement of the common boundary, as will be described in turn.

The Second Course. The second course ("Second Course") in the Lot 16 Deed is described as "thence south one and one half degrees west eighty 40/100 rods to a stake and stones;...." Plaintiffs' experts found at the terminus of the Second Course a corresponding monument which they concluded was the referenced "stake and stones," and I accept this conclusion. Additionally, Plaintiffs correctly rely on the fact that the western boundaries of abutting lots 17, [Note 11] 18, [Note 12] 19, [Note 13] and 20 all substantially coincide with the eastern boundary of Lot 16 thus located, providing proof that these properties were intended to abut each other, and dispelling the contrary interpretation, which would introduce a gap between these abutters and Lot 16. First, the deed for Lot 20 recites the same course for their common boundary ("thence north one and one half degree east..."). The deeds to Lots 16 and 20 were given simultaneously on May 13, 1870, by a common grantor, Levi Wing, and the only fair inference is that he intended the resulting parcels to abut. Second, the deed to Lot 18, conveyed on January 4, 1911, recites a western boundary course of ("south two degrees east") that is a mere three and a half degrees different from the Lot 16 Deed call for the Second Course. Moreover, this deed describes its western boundary as being "in line of land of Samuel Wing." Third, the deed to Lot 19, conveyed on March 18, 1921, recites a western boundary course of "N. 5º22'E." This course is 5.366 degrees different from the Lot 16 Deed call. This evidence all strongly indicates that the grantor of Lot 16 did not intend to create a gore to the east, and that the lots alongside it to the east have hewed closely to a boundary consistent with the Plaintiffs' view of Lot 16's eastern line. Finally, as further evidence to support the contention that these lots to the east were intended to abut Lot 16, Plaintiffs correctly point to a 1989 survey of Lot 16 ("Fitzgerald Plans") that was conducted by Gerald M. Fitzgerald to divide up the larger parcel into contemporary lots now held by the Defendants, 16, 16A and 16D. Mr. Fitzgerald accepted both the northern and eastern boundaries of Lot 16 as running along the established corresponding boundaries of Lots 14, 17, 18, 19 and 20 on the east and north.

On the other hand, Defendants contention is weakened by the fact that they do not firmly advance a definite placement for the Second Course. Defendants' expert does not place the Second Course on his "Chalk B." Rather, Defendants focus their efforts on placing Lot 16's western boundary, based upon monuments found by their expert. Nevertheless, I consider the Defendants' implicit placement of the Second Course, the eastern boundary of Lot 16, as driven by their placement of Lot 16's western boundary.

The Defendants' theory of Lot 16's western boundary is based largely on the language describing the fourth course ("Fourth Course") of the deed description, which terminates at the "stake and stones the northeast corner of Edward G. Dillingham's land...." Defendants say that the Lot 16 Deed, by this description, incorporates by reference the deed to Lot 22, [Note 14] formerly belonging to Edward G. Dillingham. Defendants' expert claims to have found these called-for "stake and stones," depicted as Corner # 1 on Chalk B, and to have verified their placement in the correct location, based on an analysis of the Lot 22 deed. That deed, in turn, calls only for adjoining properties. The southwestern corner of Lot 22 begins at "land formerly owned by Thomas Hathaway, thence easterly on said Hathaway line to said Hathaway's once outward or corner bound..." Defendants' expert found two marked trees, a tupelo tree with a hole through it and a birch tree at the location he asserts is Hathaway's "outward corner bound," marked as Corner # 6 on Chalk B. From here, following the southern boundary of Lot 22 to its southeast corner, Corner # 3 on Chalk B, the deed calls for a distance of sixty rods, or 990 feet. Beginning at Corner # 6, Defendants' expert measured 998.5 feet to a pile of stones near a large beech tree, which he explained was planted "to be able to find the corner again." These stones, claim Defendants, constitute Corner # 3 and coincide with the southwest corner of Lot 16. Thus, the line on Chalk B running between Corners # 1 and # 3 lines up to fix the southerly end of Lot 16's western boundary, as described the Fourth Course of the Lot 16 Deed.

I am unconvinced, as trier of fact, of the accuracy of the placement of Corners #1 and #3 by Mr. Seguin on his Chalk B. The quality of the monuments he relied upon is insubstantial and inconclusive, and even by his own calculation, misses the indicated length by more than eight feet. The claimed marked trees were indistinct, and did not stand out as obviously selected monuments (or as markers indicating the general proximity of survey monuments). I do not attribute any great weight to this aspect of the Defendants' surveying testimony, and accordingly do not accept the effort by them to fix the southern line of Lot 16 in this manner. This leads me to reject Defendants' placement of the Second Course.

I am persuaded to a different view than Defendants on this point, in addition, because of my conclusion that rotating Lot 16 to accommodate Defendants' placement of this course creates a substantial gore to the east of Lot 16. Unlike Plaintiffs' placement of the Second Course, Defendants' placement would no longer coincide with the western boundaries of Lots 17, 18, 19 and 20. I do not believe that the grantor of Lot 16 intended to create an unexplained gore between that property and the predecessor lot of these eastern adjoining parcels. See Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 259 (1964) ("it is proper to consider the improbability that a grantor who conveyed all her adjoining land would seek to retain such a relatively useless strip."). Instead, I find that the simultaneous conveyance of Lots 16 and 20 by common grantor Levi Wing creates an enticing inference, which I adopt, that the lots indeed were intended to abut. This is further supported by the similar deed call bearings for the eastern boundaries of the ensuing Lots 17, 18 and 19, and Mr. Fitzgerald's own reliance on those boundaries as abutting Lot 16's western boundary when he set out to divide up the older larger parcel. I find that the Second Course is as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan.

The Third Course. The third course ("Third Course") in the description of Lot 16 is described as "thence west four and three fourth degrees south twenty six 50/100 rods to a stake and stones;...." The western terminus of the Third Course constitutes the southwest corner of Lot 16. Here again, there is discrepancy in the discovery of the relevant earlier-set monuments. Both Plaintiffs' and Defendants' experts claim to have found the referenced "stake and stones" at different locations. Plaintiffs' expert testified credibly that Plaintiffs' survey found stones at a distance of 27 rods west of the southeast corner of Lot 16 pursuant to the deed call, quite close to this monument's location according to the controlling deed. Additionally, the deed for Lot 20, conveyed simultaneously with the deed for Lot 16 by Levi Wing as described above, recites the same southerly course ("west four and three fourths degrees south"), indicating the likelihood that the Third Course is simply a continuation of the southerly line of Lot 20.

The Defendants' expert found stones at a location that allegedly corresponds with the location called for in the above-referenced deed to Lot 22. These stones are claimed to be located 998.50 feet from Hathaway's "outward corner bound," described by Defendants' expert as a "marked birch tree" or a "hole in a large oak" at Corner # 3 on Chalk B. Based on these stones, Defendants claim that the southwest corner of Lot 16 is some distance to the west of the location of the southwest corner advanced by Plaintiffs. However, I cannot accept that the stones found by Defendants' expert are in fact the stones called for in the Third Course. First, despite the approximate but not exact distance measured between the postulated Hathaway's "outward corner bound" and Defendants' found stones, the Lot 22 deed does not actually state that there is a monument marking the latter. Rather, the deed locates Hathaway's "outward corner bound" by reference to the southwestern corner of Lot 22 itself. [Note 15] Second, the deed calls for a distance of 4,884 feet from Lot 22's southwest corner to Hathaway's "outward corner bound," a distance that Defendants' expert never surveyed or verified. Given the substantial distance between these points, it is unreasonable then to assume the location of Lot 22's southeastern corner is accurate by reference, ultimately, off of the Lot 22's southwestern corner, which was never surveyed or located. Third, the stones found by Defendants' expert actually fall north of Lot 22's southern boundary as depicted on Chalk B, introducing a unexplained and implausible gore between Lot 22 and Lot 26 [Note 16] to the immediate south. Lastly, the Third Course does not make reference to Lot 22. Even were the above measurements to be accurate, something I cannot conclude, they do not control placement of the Third Course. I find that the Third Course is as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan.

The Fourth and Final Courses. The western boundary of Lot 16 comprises the final two courses in the Lot 16 Deed. The full Fourth Course is described as "thence north ten and one half degrees east twenty nine 80/100 rods to a stake and stones the northeast corner of Edward G. Dillingham's land;...." The Fourth Course constitutes the southern portion of Lot 16's western boundary. From the southwest corner of Lot 16 as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan, in Plaintiffs' view the Fourth Course terminates in what today is a cranberry bog. The final course ("Final Course") is described as "thence north seventeen degrees west fifty three and one half rods to the first mentioned bound;...". The Final Course is the northern portion of the Lot 16's western boundary and its placement resolves ownership of the Disputed Areas. From the terminus of the Fourth Course, located by Plaintiffs in the cranberry bog, the Final Course returns to end at the beginning point, the "stake in pine stump" called for in the First Course.

The Defendants, on the other hand, claim that stones found by their expert in "Dillingham's northeast corner," i.e. Lot 22 described above, control the placement of Lot 16's western boundary. These stones are approximately 135.50 feet to the west of the terminus of the Fourth Course according to Plaintiffs' view of the boundaries, and locate the Disputed Areas to the east of Lot 16's western boundary and as part of the Defendants' record holdings. These stones relied upon by Defendants correspond with the western boundary of Lot 16 as depicted in the Fitzgerald Plans. Defendants also assert that these stones are in the exact location called for by the Lot 16 Deed based on a "true north" bearing, which Defendants' expert claims is the actual basis for the correct Lot 16 Deed description.

Plaintiffs offer a compelling explanation for the discrepancy between the Fitzgerald Plans and what Plaintiffs contend is the accurate Lot 16 Deed description, and I accept their explanation as persuasive and satisfying to me as the trier of fact. Mr. Fitzgerald, the earlier surveyor of Lot 16, accepted the northern and eastern boundaries of Lot 16 as running along the boundaries of Lots 14, 17, 18, 19, and 20 when measured on a magnetic bearing basis. In doing so, Mr. Fitzgerald disregarded the "scrivener's error" in placing the First Course consistent with the stones found at the undisputed northwest corner of Lot 16. The discrepancy with the Lot 16 western boundary arose only when Mr. Fitzgerald could not locate any monuments along that boundary. To establish the western boundary, then, he calculated the interior angle of Lot 16's northwest corner as written in the deed, for a resulting angle of 77º15'. In other words, although Mr. Fitzgerald accepted the First Course as placed on the ground, E4(1/4)[?]S, he nonetheless calculated the interior northwest angle based on a First Course as written: E4(1/4)[?]N. Taking into account the "scrivener's error," however, the correct angle between the First and Final Courses should be should have been computed to be 68º45'. The resulting error added an extra 8º30' to the angle between the First and Final Courses as depicted on the Fitzgerald Plans. Based on this incorrect wider angle off the line of the undisputed northern boundary, the Final Course was laid by Fitzgerald so it overlapped onto Lot 13, erroneously placing the Disputed Areas within the Defendants' properties. Plaintiffs explain, and I accept, that Defendants' monuments and "true north" theory were relied upon, improperly, to accommodate the mistaken Fitzgerald Plans, and so as to grant Defendants title to the Disputed Areas.

As I must determine which of the competing placements of Lot 16's western boundary is accurate, I need to address the issue of the bearing reference which is the basis for the Lot 16 Deed. I reject the Defendants' approach on this question. I find it unlikely that the Lot 16 Deed was written on a true north basis and conclude, instead, that the deed was written on a magnetic bearing basis. In the absence of any indication within the instrument of a contrary intention, the description in the deed is to be read as relating to the magnetic meridian. McIvers Lessee v. Walker, 13 U.S. 173 (1815) (noting the general practice of surveying according to magnetic meridian). Indeed, in the states comprising the original thirteen colonies, it was standard practice to survey in relation to the magnetic meridian. 70 A.L.R.3d. 1220 §, 2(a). See e.g. Wells v. Jackson Iron Mfg. Co., 47 N.H. 325 (1866) (courses and deeds of private lands are to be run according to the magnetic meridian when no other is specially designated). Both Plaintiffs' and Defendants' experts testified that it would be unusual for a deed description to be cast relative to a true north bearing system, with Plaintiffs' expert testifying credibly that in his eighteen years of professional licensure he had, in fact, never seen a deed written on a true north bearing. Defendants' true north theory is rendered even less plausible by their expert's testimony that the deeds to Lots 16 and 20, simultaneously conveyed as abutting lots with the same southerly boundary call, were in fact written on different bearing systems, thereby intentionally creating the substantial gore to the east of Lot 16.

Defendants' final argument justifying their placement of Lot 16's western boundary is that all of Lot 13 has been "shifted" mistakenly five rods to the east, so as to intrude into Lot 16. I resist this overture, concluding that I need not pass on competing arguments as to the correct boundaries of Lot 7 as Defendants urge me to do, because the location of that lot on the ground has no useful influence on the correct location of Lot 16; the Lot 16 Deed does not reference the location of Lots 7, 8 or 13.

I am obliged to do the best I can to set these disputed boundaries given the evidence I have. As trier of fact, relying on the legal rules governing the determination of contested boundaries, I find and rule that the Plaintiffs have proved, by a preponderance of the evidence, that their view of the line at issue is the correct one. For the reasons I have provided, I find that the western boundary of Lot 16, comprising the Fourth and Final Courses, is as shown on the Bernier Trial Plan. I conclude that both the Fredette Disputed Area and the Bechtold Disputed Area are located to the west of the common boundary between Lots 13 and Lots 16 and that Plaintiffs are the record title holders of those two disputed parcels.

Trespass

As I have determined that the Plaintiffs are the record legal title holders to the Fredette and Bechtold Disputed Areas, I now turn to the question of relief. Plaintiffs seek declaration, and also injunction, including for restoration of the Disputed Areas or, alternatively, money damages under a trespass theory. This court has jurisdiction over the trespass claim under G.L. c. 185, § 1(o), the title to the lands involved being very much in dispute. Plaintiffs request that the court issue a permanent injunction against the Fredettes ordering them to remove vehicles, machinery and personal items from the Fredette Disputed Area, and to restore the Fredette Disputed Area to its prior condition; alternatively, Plaintiffs ask for an award of damages in the amount of $35,000 against the Fredettes. Plaintiffs likewise ask the court to issue a permanent injunction against Bechtold ordering him to remove any vehicles, machinery and personal items from the Bechtold Disputed Area - including a fence and shed erected there, and ordering him to restore the Bechtold Disputed Area to its prior condition; alternatively, Plaintiffs ask for an award of damages in the amount of $35,000 against Bechtold.

Trespass is the unlawful invasion of the interest of another in exclusive possession of land, as by unpermitted entry upon it. Amaral v. Cuppels, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 85 , 91 (2005), citing Restatement (Second) of Torts § 821D comment d (1979). "A trespass requires an affirmative voluntary act upon the part of a wrongdoer...," United Electric Light Co. v. Deliso Const. Co., 315 Mass. 313 , 318 (1943), but it is not necessary, for the tort to be actionable, that the trespasser know his or her invasion violates the title or right of possession of the plaintiff ("[t]here are many instances where a man acts honestly and in good faith, only to find that he was mistaken and had committed a trespass upon his neighbor's land.") Trespass, though it involves a voluntary act, may occur without design, without actual intent to invade, as "from an intrusion by mistake...." J. D'Amico. Inc. v. Boston, 345 Mass. 218 , 224 at n.6 (1962). An ongoing invasion of the plaintiff(s land without legal right may constitute a continuing trespass, and an "intentional and continuing trespass to real estate may be enjoined. ... Damages are usually inadequate because the plaintiff is not to be compelled to part with his property for a sum of money." Chesarone v. Pinewood Builders, Inc., 345 Mass. 236 , 240 (1962). "If an injunction is granted a different rule for damages is required. ... Since his realty presumably will be returned to the status it enjoyed prior to the trespass involved, he should be compensated only for such harm as he may have suffered while the trespass continues. 'If the injury is continuous but subject to termination by later act of the wrongdoer, the measure is the lessened rental value while the injury continues. ...'" Id., at 241-242.

Section 7 of G.L. c. 242 provides that one who cuts down another's trees without license may be liable for treble damages unless one has a "good reason to believe" that the land on which the trees were located was his or her own, in which case single damages only may be awarded. G.L. c. 242, § 7. [Note 17] See Ritter v. Bergmann, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 296 (2008) (affirming award of treble damages where defendant had no "reasonable basis to believe" that he owned the land on which the trees stood). This statute reflects the legislature's judgment that a punitive approach is required to prevent wrongdoers from intentionally cutting trees down on another's property without a reasonable belief in the right to do so. Glavin v. Eckman, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 313 , 322 (2008), review denied 451 Mass. 1105 (2008). While the statute does not prescribe how damages should be measured, a land owner may opt for damages in the amount of the value of the timber that was wrongfully cut down or the diminution in property value that resulted from the cutting. Larabee v. Potvin Lumber Co., Inc., 390 Mass. 636 (1983). Recognizing, however, that market values are not always the correct measure of value of damaged property, courts have also allowed replacement or restoration costs. See Ritter, 72 Mass. App. Ct. at 307 (upholding cost of restoration as proper measure of damages for wrongful removal of timber); Trinity Church in City of Boston v. John Hancock Mut. Life Ins. Co. 399 Mass. 43 (1995) (diminution in value is not appropriate measure where there is no active market from which values may be inferred). The trial judge has broad discretion in considering evidence on the question of damages. Glavin, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 318.

However, a plaintiff who fails to prove pecuniary loss after establishing liability is entitled to only nominal damages. White Spot Const. Corp. v. Jet Spray Cooler, Inc., 344 Mass. 632 , 634 (1962). Damages based upon a plaintiff's claim of losses must be proved by a preponderance of the evidence. "This is simply a concrete application of the wider principle . . . to the effect that the complaining party must establish his claim upon a solid foundation in fact, and cannot recover when any essential element is left to conjecture, surmise or hypothesis." Id., at 635. Where an owner testifies about the value of the owner's property, the testimony must be based on more than surmise, speculation and general impressions. Von Henneberg v. Generazio, 403 Mass. 519 , 524 (1988).

In this case, there has been a paucity of proof of any damages or costs to the Plaintiffs that result from the Defendants' trespass. [Note 18] The evidence offered in support of Plaintiffs' alleged injuries stems from Judith Bernier's own testimony. Plaintiffs provided no expert testimony. Without further evidence as to the costs of the alleged harm resulting to the Disputed Areas, including but not limited to the value of the trees allegedly removed or the resulting diminution in property value, recovery of actual damages from the Defendants cannot be had.

With respect to the Bechtold Disputed Area, Plaintiffs claim that Defendant Bechtold's activities there, such as riding his ATV, storing potentially hazardous materials and his removal of various trees, have caused irreparable harm that will not be remedied by an injunction. While this may be true, the proof of loss in this regard was not meaningfully quantified in the evidence, and, given the absence of proof I decline to award any specific amount for this category of harm. While I can and will order the removal of the sheds and fence erected by Defendant Bechtold, thereby ending the invasion constituting the trespass, I cannot, in the absence of sufficient evidence put forward at trial, order the restoration of the property, nor can I award damages for alleged tree removal under either a market value or diminution in value theory.

With respect to the Fredette Disputed Area, Defendant Fredettes concede that trees indeed were cleared at some point to permit the Town of Acushnet to put in a drainage pipe for storm water running off Rene Street. However, Defendant Fredettes assert that any clearing done to the Fredette Disputed Area was done far earlier, outside the statute of limitations, and a claim for damages is thus barred by G.L. c. 260, § 2A. The evidence of the timing of this tree removal is scant. There is reason to think that much of the complained of tree removal was by the Pintos, prior Lot 16 owners with the Fredettes; the Pintos are not parties to this case. In any event, I do not need to consider whether any clearing occurred within the relevant time, given that Plaintiffs' have failed to introduce sufficient credible and reliable evidence to prove their loss. There being insufficient acceptable proof as to the value of the trees allegedly cleared by defendant Fredettes, or the quantum of damage sustained as a result of that clearing, I award no damages in this regard.

Similarly, there was an absence of satisfying proof by Plaintiffs as to the actual diminution in rental value of both the Fredette and Bechtold Disputed Areas during the time of trespass by the Defendants. These parcels were otherwise unimproved, and but a part of a larger unimproved piece of back land used by the Plaintiffs as appurtenant to their improved residential land adjoining up front. The Plaintiffs' use of the Disputed Areas was occasional, and limited to "mushrooming," nature walking, and enjoyment of wildlife. It would be hard to construct a theory of quantifiable damages for diminished rental value for the Disputed Areas given this character and the history of passive recreational use of them by Plaintiffs. What little evidence there is on this score I find unhelpful and legally inadequate, and so I will not direct entry of a judgment awarding damages to Plaintiffs on this or any other theory, the required proof therefor being lacking.

Judgment accordingly.

"Beginning at a corner in the wall between Levi Wing and Peleq Wilbur's land where formerly stood a white oak tree thence westerly in Wilbur's line to David Russell's line thence southerly on s Russell's line about fifty seven rods to land formerly owner by Thomas Hathaway thence easterly on said Hathaway's line to said Hathaway's own outward or corner bound said [sic] two hundred and ninety six rods thence easterly about sixty rods. Then beginning again at the first mentioned bound...(emphasis added)."

BRYANT BERNIER and JUDITH BERNIER v. NORMAN and MARIA FREDETTE; DAVID BECHTOLD; and STANLEY & KATHRYN CHABEREK

BRYANT BERNIER and JUDITH BERNIER v. NORMAN and MARIA FREDETTE; DAVID BECHTOLD; and STANLEY & KATHRYN CHABEREK