Introduction

This case was brought to determine the location of the common

boundary between abutting properties in Truro. Both

the trial and the judgment that followed were based on a

central, agreed fact: the entirety of the defendants' property was

contained within the boundaries of the land conveyed in an 1838

deed (Paine to Small, Apr. 2, 1838, Barnstable Registry of Deeds

Book 41, page 180) (hereafter "41/180") and thus the common

boundary did not extend beyond the lines of the land described in

the 41/180 deed. It now appears that this may not be true.

Nine months before trial, by deed from Charles Francis, Jr.

(Francis to McDermott/Zakin, Aug. 15, 2006) (hereafter, the

"new deed"), the defendants acquired additional land to the south

of 41/180 (more precisely, Mr. Francis' interest, if any, in that additional land)

that may also abut the plaintiff's property, leaving

that portion of the common boundary unadjudicated. That the adjudication

is thus incomplete is entirely the defendants' fault.

The new deed was not recorded until April 2012 - years after

trial and long after judgment was entered - and its existence was

never disclosed to the plaintiff or this court. The plaintiff only

learned of it after checking the Registry, and this court only after

the plaintiff filed the present motion.

The plaintiff has now moved to vacate the judgment and re-open

these proceedings pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2) (newly

discovered evidence) and Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(3) (fraud or

other misconduct of a party). That motion is DENIED IN PART

and ALLOWED IN PART. This court will not revisit its determination

of the common boundary line between the plaintiff and

the 41/180 portion of defendants' land. It was, and remains, the

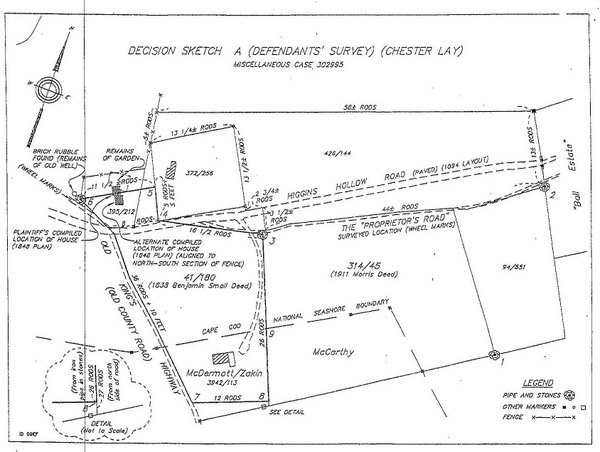

line between points 8 and 9 as shown on Decision Sketch A (attached).

Nor will this court revisit its determination of the location of point 7 and thus the southern boundary of the defendants'

land insofar as it derives from the 41/180 deed (the line between

points 7 and 8). Contrary to the plaintiff's contentions, neither

the new deed nor the circumstances underlying the new deed affect

those determinations in any way. The judgment, however,

purported to adjudicate the entirety of the parties' common

boundary (the relief requested in the plaintiff's complaint) and,

because of the new deed, may not have done so. Accordingly, the

judgment is VACATED and these proceedings RE-OPENED to

determine, and only to determine (1) whether Mr. Francis owned

the land south of 41/180 he purported to convey to the defendants

and, depending upon that answer (2) the common boundary line

between that land and the plaintiff's.

Discussion

As noted above, this case is a dispute between the owners of abutting

properties in Truro regarding the location of their common

boundary. It was tried, and judgment was based, on an agreed fact:

the defendants' land was a portion of a larger tract described in an

1838 deed from Jeremiah Paine to Benjamin Small (41/180) [Note 1]

Thus, the common boundary could not go beyond the lines of

41/180. Anything more was a nullity unless it originated in a different

source. See Bongaards v. Millen, 440 Mass. 10 , 15 (2003).

No other source was identified, evidenced or argued at trial.

The defendants, through their surveyor Chester Lay, argued three

different alternatives for the location of the eastern and southern

boundaries of 41/180. [Note 2]

The first, and the one I found persuasive, used 41/180's 36 rod 10

feet western measurement starting from the existing iron pipe

and stones at point 6, the 26 rod eastern measurement starting

from the existing iron pipe and stones at point 3, and the 12 rod

measurement described in 41/180 as its southern length, to determine

the southwestern and southeastern corners of 41/180

(points 7 and 8) and thus the common boundary line between

41/180 and the plaintiff's property (the straight line between

points 8 and 9). See Decision Sketch A; Decision at 10-17; Memorandum

and Order on Plaintiff's Motion for New Trial and to

Amend Findings (Aug. 2, 2011).

The second alternative used a 27 rod distance on the east - the

length of the call for the western boundary of an abutting property

as described in the 1911 Morris deed (Heirs of Joseph and

Louisa Morris to James Morris (Sept. 7, 1911), recorded in the

Barnstable Registry of Deeds at Book 314, page 45)

("314/45")) [Note 3] - beginning at a more northerly starting point than

the 26 rod measurement in 41/180. [Note 4] Unlike the first alternative, it

did not result in a confident location for the southeastern corner

of 41/180 and was thus rejected. [Note 5]

The defendants' third alternative disregarded 41/180's western,

eastern and southern distance measurements entirely, focused

solely on the southern abutter ("lands of Doane Rich") as the

controlling guide, and claimed that the lands of Doane Rich began

at the straight line shown on Decision Sketch A below the

point 7 to point 8 line (the "straight line theory"). It too was unpersuasive. The parties agreed that the immediate southern abutter was "the lands of Doane Rich." Statement of Agreed

Facts at 5, ¶21. But the boundary between 41/180 and those lands

was not the straight line shown on Decision Sketch A, parallel

with another straight line further south. Sec Trial Ex. 113A

(Lorraine S. Francis parcel). The defendants' contention that it

was that straight line is simply incorrect. The distance measurements

in 41/180 are given specifically, not as "more or less," [Note 6]

and are inconsistent with that straight line. Instead, they produce

an angle at the south. See Decision Sketch A (the line between

point 7 and point 8). The Doane Rich lands bordered this angle. [Note 7]

My findings regarding the southern boundary of 41/180 showed

the existence of a gap between that parcel and the Lorraine Francis

property to the south. [Note 8] The defendants claimed ownership of

the bulk of this gap in Plan Book 610, Page 69 (May 11, 2006)

("610/69"), but had no record title basis to do so. [Note 9] In recognition

of this, the defendants obtained a deed from the person whom

they believed owned this "missing" land, Mr. Charles Francis Jr.,

granting them the entirety of his interest, if any, in the land within

610/69. [Note 10] They did so nine months before trial. Deed, Charles

Francis Jr. to Robert McDermott, Ellen McDermott and Mikhail

Zakin (Aug. 15, 2006) (the "new deed"). However, they neither

recorded the deed nor disclosed its existence to the plaintiff or

this court. In fact the deed was recorded only recently, long after

the trial concluded and judgment entered, and discovered by the

plaintiff only after it was recorded. Barnstable Registry of Deeds,

Book 26248, page 257 (Apr. 17, 2012). On this basis, the plaintiff

has now moved to vacate the judgment pursuant to Mass. R. Civ.

P. 60(b)(2) (newly discovered evidence) and Mass. R. Civ. P.

60(b)(3) (fraud or other misconduct of a party). The new deed,

plaintiff argues, shows that the defendants lied when they said

their title derived solely from 41/180 and caused the case to be

tried on a falsehood, leading to the wrong result.

To vacate a judgment pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2), the

newly discovered evidence must not only be "new" but also "credible,

material, admissible, and likely (if believed) to affect the outcome."

J. Smith & H. Zobel, 7 Massachusetts Practice (Rules

Practice) 2nd Ed., §60.8 at 377, 379 (2011-2012 Supp.), citing

Wojicki v. Caragher, 447 Mass. 200 , 215 (2006); Cahaly v.

Benistar Property Exchange Trust Co., Inc., 68 Mass. App. Ct. 668 , 674 (2007). Similarly, to vacate a judgment pursuant to Mass.

R. Civ. P. 60(b)(3), the fraud or misconduct must be "result-affecting

chicanery." Id., §60.9 at 379. "Mere failure to disclose

colorably pertinent facts to the opponent or to the court does not

rise (or fall) to the level of fraud on the court." Id., §60.9 at 380,

citing Winthrop Corp. v. Lowenthal, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 180 , 184

(1990).

I agree that the new deed should have been disclosed to the plaintiff

and to this court at the time it was executed and delivered. [Note 11] I

agree that its absence from the case caused an incomplete adjudication

in the sense that the parties' common boundary beyond the

edge of 41/180 has not been addressed. But it would not have

changed, and does not change, this court's judgment of the parties'

common boundary line insofar as the defendants' title derives

from 41/180. Months of work, on both sides, went into

searching the titles for both the plaintiff's and defendants' land.

The parties, their counsel, and their surveyors and title examiners

all agreed that the defendants' title (pre-new deed) derived solely

from 41/180. See Statement of Agreed Facts at 2-3, 4. The parties,

their counsel, and their surveyors and title examiners all

agreed that neither Mr. Francis nor any of his predecessors were

in the 41/180 chain. Id. at 2-3 (chain of title for defendants' land).

The parties, their counsel, and their surveyors and title examiners

located the boundaries of 41/180 based on their competing analyses

of the same deeds, plans and physical features. There is

nothing to suggest, and certainly no affidavit from the plaintiff's

expert to suggest, that any of these analyses would have changed

with the disclosure of the new deed. Indeed, it could not have

changed any of these analyses because it post-dated (2006) all

the relevant evidence in the case. At best, it could only have affected

my assessment of the credibility of Mr. Lay's testimony in

support of defendants' "straight line" theory (perhaps the reason

the defendants did not disclose it) but, as related above, I did not

find that testimony credible in any event.

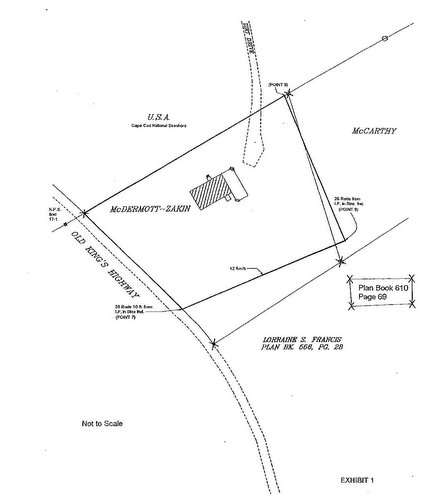

The new deed, however, leaves unadjudicated the common

boundary between that property and the plaintiff's. There may be

no common boundary in that location, either because the plaintiff's

parcel does not extend below point 8 or, if it does, because it

does not go as far west as the 610/69 line (see Exhibit 1, attached). [Note 12]

It is also possible that Mr. Francis had nothing to convey

(his chain of title has not yet been adjudicated in this case).

These points must be addressed to grant the relief sought by the

plaintiff in this case - the adjudication of the complete common

boundary line between the plaintiff and the defendants.

Conclusion

For the reasons set forth above, the judgment is VACATED and

these proceedings RE-OPENED to determine, and only to determine

(1) whether Mr. Francis owned the land south of 41/180 he

purported to convey to the defendants and, depending upon that

answer (2) the common boundary line between that land and the

plaintiff's. The parties shall contact the session clerk to schedule

a status conference for the purpose of establishing the future

course of these proceedings.

SO ORDERED.

The primary support for defendants' "straight line" theory was their surveyor,

Chester Lay's speculation that the then-abutting parcel on the south was a "wood

lot" and "the majority of the wood lots in this area are rectangular with parallel

lines." (Trial Transcript, Day 8 at 101-102). I did not find this credible. First,

there is no particular reason why the abutting parcel to the south should be considered

simply a "wood lot." It was on Old County Road (now Old King's Highway)

and thus an accessible and attractive site for a home or other structure.

Second, there is no reason why even a "wood lot" could only have parallel

straight-line boundaries in this instance where the deed used the abutting properties

as monuments. Third, even Mr. Lay admits there are exceptions to his "parallel

straight line" theory for wood lot boundaries. He did not say all wood lots in

this area had parallel, straight-line boundaries; only the majority of them.

REGAN McCARTHY v. ROBERT McDERMOTT, ELLEN McDERMOTT and MAKHAIL ZAKIN

REGAN McCARTHY v. ROBERT McDERMOTT, ELLEN McDERMOTT and MAKHAIL ZAKIN