SUSAN LEAHY v. DMITIRI GLUKHOVSKY and ALEXANDRA KELLER

SUSAN LEAHY v. DMITIRI GLUKHOVSKY and ALEXANDRA KELLER

MISC 08-370825

September 4, 2012

NORFOLK, ss.

Piper, J.

SUSAN LEAHY v. DMITIRI GLUKHOVSKY and ALEXANDRA KELLER

SUSAN LEAHY v. DMITIRI GLUKHOVSKY and ALEXANDRA KELLER

Piper, J.

I. INTRODUCTION

This action commenced on February 14, 2008 with the filing in this court of a verified complaint. The plaintiff, Susan Leahy ("Leahy" or "Plaintiff"), requests determination by the court of the boundary line between her property ("Leahy Property") and the adjoining property ("Glukhovsky Property") of the defendants, Dmitri Glukhovsky ("Glukhovsky") and Alexandra Keller (together, "Glukhovsky" or "Defendants"). Plaintiff also requests the court to order removal of encroachments on her property and an award of damages for the willful girdling of her trees under G.L. c. 242, § 7, as well as attorney's fees under G.L. c. 231, § 6F.

The parties filed a joint case management conference statement and then appeared for the case management conference on April 30, 2008. Glukhovsky contended that the rights of additional parties - namely, three other nearby landowners in the subdivision in which the Leahy Property and the Glukhovsky Property lie - might be affected by the outcome of the litigation. The court (Piper, J.) directed Leahy and Glukhovsky that if they wished to join any additional parties, they were to submit a motion requesting joinder by July 15, 2008. On July 3, 2008, the parties filed a joint status report in which they set out time frames for their preparation of the case for decision by the court. Neither party submitted a motion to join additional parties. (The court has proceeded with the trial and decision of this dispute only as between Leahy and Glukhovsky, and without adjudicating in this decision the rights and titles of any other neighboring landowners.)

On September 9, 2008, Plaintiff filed a motion to compel documents from the Defendants and on September 23, 2008, the court heard and allowed the Plaintiff's motion. On December 30, 2008, the court denied without prejudice Defendants' motion to dismiss for failure to comply with Land Court Rule 4. On March 13, 2010, the parties filed a joint pretrial memorandum and appeared for a pretrial conference on March 17, 2010.

This case came on for trial before the Land Court (Piper, J.) on June 17 and July 23, 2010. A court reporter, Pamela St. Amand, was sworn to transcribe the testimony and proceedings. Plaintiff called three witnesses: Plaintiff Susan Leahy; James Toomey, the son and employee of Plaintiff's previous surveyor; and Rod Carter, a professional land surveyor, who gave opinion testimony. [Note 1] Defendants, appearing pro se, called two witnesses: Defendant Alexandra Keller, and Leo J. Glover, a professional land surveyor, who gave opinion testimony. The parties introduced into evidence a total of fifty-eight exhibits and employed several chalks, all as reflected in the transcripts.

At the close of the taking of evidence, the court postponed closing arguments and instructed counsel to await the receipt of the trial transcripts, and then to file and serve proposed findings of fact and rulings of law, and posttrial memoranda. Plaintiff and Defendants each filed requests for findings of fact and rulings of law, and posttrial memoranda. On October 15, 2010, the court heard closing arguments. After the trial concluded, the court, based on its review of the record evidence, informed the parties that the court would take judicial notice of the papers and proceedings in two relevant Registration cases in this court, Nos. 9125 and 30122, concerning nearby land whose titles have been registered and confirmed by this court pursuant to G.L. c. 185. The court invited the parties to file supplemental memoranda addressing these cases. They did so, and the court took the case under advisement. I now decide the case.

II. FINDINGS OF FACT

On all of the testimony, exhibits, stipulations, and other evidence properly introduced at trial or otherwise before me, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, and taking into account the pleadings, and the memoranda and argument of the parties, I now decide the case, making the following findings of fact and rulings of law.

A. Relevant Registration Cases, Recorded Deeds, and Plans

1. Leahy is the owner of the property located at 21 Algonquin Road, in Canton, Massachusetts, which is more particularly described in the deed dated September 24, 1997 and recorded with the Norfolk County Registry of Deeds ("Registry") at Book 12003, Page 183. When Leahy and her former husband divorced, a deed ("Leahy deed"), from Robert E. Casagrande, Jr. and Susan Leahy f/k/a Susan Leahy-Casagrande to Susan Leahy, individually, was recorded with the Registry on November 18, 2003 at Book 20200, Page 505. The Leahy deed (Exhibit 6) describes her property as follows: "The land with the buildings thereon situated in Canton, Norfolk County, Massachusetts, shown as Lot 22 in a Plan of Sections 3 and 4 by G.F. Hollinshead, C.E., dated October 13, 1953, and recorded with Norfolk Deeds in Book 3251, Page 450 and bounded and described as according to said plan as follows: Northeasterly by Algonquin Road on [sic] hundred fifty (150) feet; Southeasterly by Lot 24, two hundred (200) feet; Southwesterly by land now or formerly of Ethel F. English, one hundred fifty (150) feet; and Northwesterly by Lot 20, two hundred (200) feet. Containing 30,000 square feet."

2. Defendants Glukhovsky and Keller are the owners of the property located at 23 Algonquin Road, in Canton, Massachusetts, which is more particularly described in the deed ("Glukhovsky deed") dated December 22, 2003 and recorded the following day with the Registry at Book 20355, Page 7. The Glukhovsky Property abuts the Leahy Property, lying immediately to the east of the Leahy Property. Neither party's current deed makes reference to any specific monumentation other than references to abutting land. The Glukhovsky deed (Exhibit 13) describes the property as follows: "A certain parcel of land situated in said Canton being Lot 24 on a plan by G.F. Hollinshead, C.E. dated October 13, 1953, and recorded with Norfolk Deeds as Plan #428 of 1954 in Book 3251, Page 450, bounded and described according to said plan as follows: Northeasterly by Algonquin Road, one hundred fifty (150) feet, Southeasterly by Lot 26, two hundred (200) feet, Southwesterly by land of Ethel F. English, one hundred fifty (150) feet, and Northwesterly by Lot 22, two hundred (200) feet. Containing 30,000 square feet."

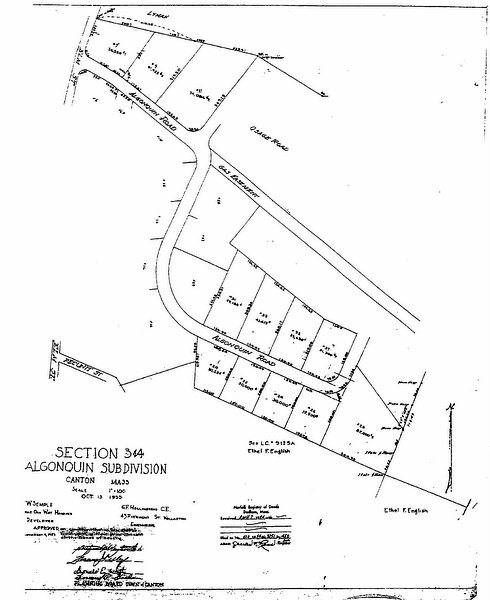

3. Both the Leahy Property and the Glukhovsky Property were established based on a 1953 Subdivision Plan ("Subdivision Plan" "subdivision plan" or "Exhibit 1") titled "Section 3 and 4, Algonquin Subdivision, Canton, Mass.," recorded in the Registry as No. 428-1954 Book 3251, Page 450. A copy of the Subdivision Plan is attached to this decision. According to the Subdivision Plan, which was prepared for developer J.W. Semple by civil engineer G. F. Hollinshead, the two lots in dispute are rectangles, each measuring 150 feet wide and 200 feet deep, giving the respective properties each 30,000 square feet of land area. Nothing in the parties' deeds, on the Subdivision Plan, or otherwise, suggests that the property angles for both lots are anything other than ninety degrees, and I find that all the corners of the two lots turn angles of ninety degrees.

4. The Subdivision Plan depicts five parcels on the south side of Algonquin Road, numbered, running west to east: Lots 20, 22, 24, 26, and 28. (Taken together these parcels shown on the Subdivision Plan, the "Subdivision" or "subdivision"). Leahy owns Lot 22 and Glukhovsky owns Lot 24. According to the Subdivision Plan, the total distance from the southwest corner of Lot 20 to the southeast corner of Lot 28 is 881.11 feet. [Note 2] The words "See L.C. # 9125A Ethel F. English" appear just south of these five lots in the subdivision on the Subdivision Plan. The property in dispute consists of an area 200 feet long (the length of the boundary line between the parties' two parcels) with an approximate width of 13 feet.

5. Several Land Court registration cases provide guidance in this matter. After becoming aware of the likely importance of these cases, I informed the parties that I would take judicial notice of registration cases in the vicinity of the dispute filed under G.L. c. 185, § 26 et seq., and I have provided the parties with an opportunity to file posttrial memoranda on the matter, an invitation they have accepted.

6. Registration Case No. 9125, brought by Ethel L. English in 1922 and finally registered January 30, 1934, concerned land south and east of where the subdivision containing the parties' land sits today, and includes three relevant plans. The 9125A plan, dated November 18, 1922, labeled 9125A, and in evidence as Exhibit 30 ("petitioner's plan"), [Note 3] the 9125A2 plan, dated January 8, 1930, and in evidence as Exhibit 32 ("Aspinwall plan"), [Note 4] and the decree plan, received for registration by this court's Norfolk land registration district on January 30, 1934, and in evidence as Exhibit 31 ("decree plan").

7. In 1930, while Ethel F. English's registration case was pending, the Hoosic Whisick Club, a Massachusetts corporation, granted Ethel F. English approximately seven acres of land depicted as lot A on the Aspinwall plan. The land was adjacent to the L-shaped property Ethel L. English eventually registered in 1934. This deed (the "English deed") was recorded with the Registry at Book 1884, Page 326. The lot A land itself (the "English parcel") never has had its title registered and confirmed; the English parcel lies to the west and north of the land which English did register. On the Aspinwall plan, the English parcel is depicted as, beginning in its northwest corner, running southeast 877.84 feet, then south for 106.31 feet to a stone post, then south 298.22 feet to a stake and stones, then northwesterly for 269.36 feet, continuing northwesterly for 393.95 feet to a stake and stones, then north for 164.69 feet to a stone bound, continuing north 74 feet, then northwest for 82 feet "+/-," then north for 245 feet along the remains of a stone wall to the starting point. The unregistered English parcel abuts, to the west and the north, the "L-shaped" parcel of land ("English registered land") whose title in Ethel L. English this court first registered and confirmed in 1934.

8. The northern boundary of the unregistered English parcel lies just south of and abuts what is now the subdivision containing the parties' land, a fact confirmed by both parties' deeds. The Leahy deed describes her property as bounded "southerly by land now or formerly of English one hundred fifty feet" and the Glukhovsky deed describes their property as bounded "southwesterly by land of Ethel F. English, as shown on said plan, one hundred fifty (150) feet."

9. In 1930, Ethel F. English also granted the Hoosic Whisick Club approximately seven acres of land (the "Whisick parcel")- a portion of the tract originally sought to be registered in Case No. 9125 - depicted as lot B on the Aspinwall plan. This deed was recorded with the Registry at Book 1884, Page 325. The Whisick parcel, though included on the petitioner's plan, was not included as part of the land shown on the decree plan as registered and confirmed by the court. However, the northeast corner of the English parcel (lot A) as it came to be shown on the decree plan, is the same point as the southwest corner of the Whisick Parcel (lot B), as shown on the Aspinwall plan.

10. The decree plan was prepared by an engineer of this court based on the petitioner's plan. The engineer did not appear to have relied upon the Aspinwall plan to make the decree plan, although the actual decree of registration of this court (Smith, J.) recognizes the conveyances described above, that the portion of the petitioner's plan appearing as lot B on the Aspinwall plan was dismissed from the registration proceeding, and that the parcel labeled as lot A on the Aspinwall plan (which did not appear in the petitioner's plan) also was not to be included in the decree of registration.

11. In 1961, after the Subdivision Plan was recorded, Henry C. Meadow and Charles P. Lyman brought a petition to register title to land to the west of both the English parcel, and the land shown on the subdivision plan. This case, Registration Case No. 31022, produced two relevant plans of which I take judicial notice, in addition to the one plan entered into evidence by the parties: the 31022A plan, dated December 4, 1965 and filed with the District April 5, 1966; the 31022B plan, depicting a subdivision of the land on the 31022A plan, and registered November 14, 1967; and the 31022C plan, depicting a subdivision of land on the 31022B plan, registered December 15, 1972, and in evidence as Exhibit 38.

12. The eastern boundary of the parcel of land registered in case 31022 abuts the western boundary of the unregistered English parcel, as well as a portion of the Subdivision. Beginning with an iron pipe found in the vicinity of the northeast corner of parcel 31022, as depicted on Plan No. 31022A, the eastern boundary runs south 245.96 feet to a stone bound, then southeast 79.68 feet to a stone, then south 74.00 feet to stone bound, then further south 164.69 feet. These distances correspond closely, although not precisely, to the distances recorded in the English deed and depicted on the Aspinwall plan. The largest discrepancy, approximately 2.32 feet, is between the distance of 79.68 feet on Plan No. 31022A and the 82 feet "+/-" described in the English deed and depicted on the Aspinwall plan.

13. The 9125B plan, drawn in 1965 and filed with this court's District on September 21, 1966, represents a division of the English registered land shown on the decree plan. The 9125B parcel has as its northern bound a portion of the boundary line shown as 368.08 feet on the Aspinwall plan. The northern bound of the new parcel shown on the 9125B plan is 260.00 feet. A concrete bound, shown on the 9125B plan as "C.B." was set on September 13, 1966 to monument the western terminus of the northern boundary line of this land. [Note 5]

14. Land Court Plan No. 31547G (Exhibit 36) depicts land that once was part of the easternmost portion of the English registered land shown on the decree plan, and later the 9125B plan. Plan No. 31547G is part of a plan filed in the Land Court on June 2, 1966 and received for registration by the Norfolk District on August 1, 1967, noted on Certificate of Title No. 82828 in Registration Book 415, Page 20. In the northwest corner of the 31547G plan, the name "Ethel F. English" appears to refer to the English unregistered parcel. The northernmost boundary line depicted on the 31547G plan, with its two segments totaling 260.00 feet, is the same boundary line depicted as the northern boundary on the 9125B plan. 15. The 31547G plan depicts a concrete bound 108 feet "+/-" east of the northeastern corner of the English parcel, along the northern boundary line. I find that this is the same concrete bound set in September of 1966 and shown on the 9125B plan. The original northern boundary line on the decree plan was 368.08 feet; 260.0 feet were carved off to create the lot on the 9125B plan, leaving 108.08 feet. Thus, 108.08 feet northwesterly from the concrete bound on the 31547G Plan is the location of the southeast corner of the Subdivision, shown as a stake & stone on the Subdivision Plan.

B. The Parties' Competing Surveys

16. In June 2004, preparing to build an addition to her home, Leahy hired a land surveying firm, Toomey-Munson & Associates, to prepare a plan of her property. At around the same time, the Glukhovskys hired another licensed land surveyor, Leo J. Glover, to survey the Glukhovsky land--so the Glukhovskys might build an addition to their home.

17. The parties' surveyors did not communicate with one another while each undertook to survey the abutting parcels in 2004. Upon completion of the surveys, Toomey-Munson & Associates concluded that certain iron pipes marked the two southern corners of the Leahy Property, including the easterly one which Toomey-Munson concluded was the location of the southern end of the Leahy-Glukhovsky common boundary. Leo Glover separately concluded that, instead, nearby iron rods marked the southern corners of the Glukhovsky and Leahy property. [Note 6] Both markers appear in the vicinity of the property line between Leahy and Glukhovsky along the shared rear boundary of the subdivision. The difference in distance between the iron rods and iron pipes is approximately thirteen feet and provides the basis for the dispute. The town granted each party a building permit, and construction commenced on each project in the summer of 2004.

18. In 2006, Glukhovsky contacted his surveyor, Glover, to file an extension on his permit and amend it to include a new deck. This appears to be the first time anyone noticed a potential problem. At trial, Glover explained that it was clear to him upon his visit to the Glukhovsky property in May of 2006 that there did not appear to be, as required by the Canton zoning by-laws, forty feet open between the two homes. The designated side setback in the town of Canton is twenty feet. With the additions in place, only 34.4 feet separated the nearest walls of the two houses (not including Glukhovsky's new deck, which extends several additional feet towards the property line with Leahy).

19. In June 2006, Glukhovsky built a six-foot high wooden fence that is designed to separate the Glukhovsky property from Leahy's. The fence sits approximately thirteen feet from the corner of Leahy's house and runs approximately the depth of the property, in a line roughly perpendicular to the street. Leahy argues that the fence encroaches on her land by approximately thirteen feet. Glukhovsky contends that the fence is 1.5 feet within his property.

20. Much of the trial testimony centered on locating the southeastern corner of the subdivision. The Subdivision Plan depicts that a stake and stones monument once marked the southeastern corner. The parties and their surveyors agree that no such monument exists in that location today. Rod Carter based his testimony, and his proposed location of the southeastern corner, on the opinion that iron pipes marked the true two southern corners of the Leahy Property, as well as the southern corners of the four other lots in the Subdivision. As described below, Leo Glover based his testimony on his opinion that instead, iron rods marked the correct corners of the Glukhovsky Property. For the reasons which follow, I conclude that Rod Carter, and Toomey-Munson before him, correctly located the southeastern corner of the subdivision.

21. Carter testified that at some unknown point in time, an iron pipe replaced the stake and stones as the monument marking the southeastern corner of the Subdivision. [Note 7] Carter discovered such an iron pipe in the vicinity, and indicated his findings on Exhibit 29. To support this theory, Carter measured from the iron pipe heading west until he reached another iron pipe near the southeastern corner of the Glukhovsky property, finding a distance of 466.11 feet between the two pipes. According to the Subdivision Plan, the distance between the southeastern corner of Lot 24 - the Glukhovsky Property - and the southeastern corner of the subdivision is exactly 466.11 feet. [Note 8] Measuring 150 feet further west, Carter found another iron pipe and concluded that it marked the southeastern corner of the Leahy Property (as well as the southwestern corner of the Glukhovsky property). Carter opined that this iron pipe represents the boundary line between the Leahy Property and the Glukhovsky Property. Finally, Carter found a fourth iron pipe 150 feet further west and concluded that it marked the southwestern corner of the Leahy Property. According to the Subdivision Plan, the width of the Leahy property and the Glukhovsky Property is each 150 feet.

22. I find that the Toomey-Munson plan dated January 10, 2007 ("Exhibit 24" or "Toomey-Munson Plan") depicts the most accurate representation of the subdivision and surrounding property. Toomey-Munson reviewed several recorded plans, deeds, and at least six registered Land Court plans of the surrounding area adjudicated by this court before making the conclusion as to the length of the southern rear boundary of the subdivision. The firm surveyed not only the land in dispute, but the entire surrounding area and placed the subdivision in context with registered Land Court plans. I find, however, that none of the surveyors correctly located the boundary between Leahy and Glukhovsky because Toomey-Munson did not adequately consider and address the shortage it discovered in the shared rear lot line--in light of the effect that this overall shortage would necessarily have on all five parcels in the subdivision. [Note 9] There is a shortfall in the overall rear, southern, line of the five lots shown south of Algonquin Road on the Subdivision, which runs between two fixed, known, and previously-adjudicated points--meaning that there is a smaller distance lying between these two points than the distance indicated on the Subdivision Plan. The court finds and rules that the proper boundary between the parties only may be determined after apportioning this deficiency to the five parcels in proportion to the length of their respective rear lot lines as a fraction of the total rear line of the Subdivision.

C. The Southeastern Bound of the Subdivision

23. The southeastern boundary of the Subdivision is that iron pipe shown on the Toomey-Munson plan 108.08 feet west of the concrete bound (set in September 1966) with a Land Court disk.

24. The southeastern boundary of the Subdivision, as depicted on the Toomey-Munson Plan, is 106.31 feet to the north of the fieldstone with an X-cut, and a ring of stones, located by Toomey-Munson. This 106.31 measurement precisely matches the Aspinwall plan, which depicts a stone post 106.31 feet south of the southwestern corner of the Whisick Club parcel (or alternatively, the northeastern corner of the English parcel). Although the monumentation has changed over the last eighty-two years, the distance remains identical. The decree plan also shows this to be 106.31 feet.

25. The Subdivision plan depicts a stake and stones monument at the southeastern corner of the subdivision, and another stake and stones monument 99.65 feet northeast, followed by a stone heap 105 feet further northeast along the same line. The petitioner's plan shows two stake-and-stones monuments separated by 99.65 feet, followed by a stone heap 105 feet to the north. The Aspinwall plan also shows the stone heap, and 105 feet to the south, a stake and stones, but the dimension between the two stake-and-stones monuments is missing.

26. Defendants argue that the southeastern corner of the subdivision did not start with the iron pipe but instead began as much as 6.5 feet south of that pipe. This way, they argue, by starting the eastern terminus of the shared rear lot line further south, and ending the western terminus further north, it was possible to arrive at 881.11 feet (as originally allotted on the Subdivision Plan) without encroaching on land on registered in either Case Nos. 9125 or 31022. The defendants' surveyor, Leo Glover, arrived at this conclusion based on his theory that resolving a "missing dimension" between the two stake-and-stones monuments on the Aspinwall plan would shift the southeastern corner of the subdivision 6.5 feet to the south. This line is also the eastern boundary of the subdivision.

27. It bears repeating that on the Case No. 9125 petitioner's plan (Exhibit 30), starting from a stone post depicted on the western boundary of the L-shaped parcel Ethel English registered in 1934, and running northerly, there are three relevant distances depicted on the western boundary of parcel the registered land: 98.85 feet to a stake and stones, 99.65 feet to another stake and stones, and 105 feet to a stone heap. The Aspinwall plan (Exhibit 32), like the petitioner's plan and the decree plan, depicts a distance of 106.31 feet from the stone post to the northeastern corner of the English parcel (or alternatively, the southwestern corner of the Whisick parcel). There is, however, no monument depicted at this corner, nor is there a distance provided on the Aspinwall plan between this corner and the stake and stones to the north - this is the "missing dimension." The third distance of 105 feet between the stake and stones, and stone heap matches the petitioner's plan.

28. Glover opined that the "missing dimension" on the Aspinwall plan was in fact 99.65 feet, as depicted on the petitioner's plan. The Subdivision Plan shows 99.65 feet between the two stake-and-stones monuments. But because the Aspinwall plan also depicted a distance of 106.31 feet between the stone post and the unmarked northeastern corner of the English parcel, Glover theorized that inserting the 99.65 feet into the missing dimension on Plan No. 9125A2 would shift the southeastern corner of the subdivision approximately 6.5 feet south of the northeastern corner of the English parcel. In other words, Glover argued that the although the iron pipe found near the southeastern corner of the subdivision may mark the northeastern corner of the English parcel, it did not represent the subdivision corner as well. Carter argues the missing dimension must be 93.19 feet, and by inference, the petitioner's plan just had it wrong - it was corrected on subsequent plans filed on behalf of Ethel English.

29. The 106.31-foot measurement was adjudicated by this court in arriving at the decree in the in rem registration proceeding. Despite appearing on the petitioner's plan, and the Aspinwall plan, the dimensions and monuments north of that 106.31-foot span were not adjudicated as part of plans registered by this court. The decree plan in Case No. 9125 does not depict anything north of the 106.31-foot span, because the parcel shown as lot B on the Aspinwall plan was withdrawn or dismissed from the registration proceeding prior to final adjudication. Thus, it should be the 106.31-foot distance that holds, not the numbers on the other plans to the extent they contradict this.

30. Toomey-Munson did make measurements south of the subdivision along the same line and corroborated the distance of 106.31 feet from the northeastern corner of the English parcel (or southwestern corner of the subdivision) to the stone post that appears on the Aspinwall plan. No parties' surveyor claims to have located a monument either 99.65 feet or 93.19 feet north of the iron pipe. There is no evidence whether any of the monuments depicted on Aspinwall plan north of this still exist today. [Note 10] Finally, Glover conceded at trial that even if the shared lot line (between the Subdivision and the English parcel) were to start 6.5 feet south of the iron pipe, Glover would not be able to create a plan that would depict the results he came to in 2004 and 2006 when he used the stone bound and iron rods to determine Glukhovsky's property lines. Put another way, even if the shared rear lot line is 881.11 feet in length, the position of the iron rods could not be reconciled with the property distances depicted on the Subdivision Plan and described in the parties' deeds. I conclude that the iron rod near the Glukhovsky Property's southern boundary line does not mark the Leahy-Glukhovsky border.

D. The Southwestern Bound of the Subdivision

31. I also conclude that Toomey-Munson accurately located the western terminus of the southern line of the subdivision by surveying the property south and west of the subdivision and matching it to registered land depicted on the relevant plans from Cases Nos. 9125 and 31022. As shown on the Toomey-Munson Plan, Toomey-Munson found that another iron pipe marks the southwestern corner of the subdivision. This monument corresponds to Plan No. 31022A, which shows an iron pipe in the vicinity of the northeast corner of the parcel registered in 31022. This iron pipe marks the southwest corner of the Subdivision. Furthermore, the Toomey-Munson Plan depicts a partial stone wall running southeast from the iron pipe, which corresponds to the remains of a stone wall depicted on both the Aspinwall plan, and the 31022A plan.

32. Finally, the Toomey-Munson measurements from the southwestern corner of the subdivision, as shown on the Toomey-Munson Plan, are consistent with the distances depicted on Plan No. 31022A. Toomey-Munson measured 245.09 feet south from the iron pipe depicted in the vicinity of the northeast corner of the parcel registered in Case No. 31022, then 79.68 feet southeast along the eastern boundary of that parcel. This corresponds almost exactly with the measurements on Plan No. 31022A, which show 245.96 feet from the iron pipe to a stone bound, and 79.68 feet from the stone bound to a stake. This also corresponds closely with the Aspinwall plan, which lists the first distance as 245 feet and the second as 82 feet "+/-." I am led to find that the iron pipe depicted in the vicinity of the northeast corner on Plan No. 31022A is the southwest corner of the subdivision. As explained above, Toomey-Munson found such an iron pipe and recorded it on their plan, and in these findings I adopt their location of the Subdivision's southwest corner.

E. Bounds of Individual Lots Within Subdivision

33. Glukhovsky's surveyor, Leo J. Glover, did not consider the surrounding registered land when he first prepared a plan for Glukhovsky in 2004. Instead, Glover testified that he reviewed only the recorded Subdivision Plan. In conducting his survey, Glover relied on a stone bound found along a curve in Algonquin Road to the northeast of Glukhovsky's property. The stone bound does not appear on the Subdivision Plan. According to Glover, however, it does correspond with the iron rods Glover found in the corners of Glukhovsky's property. [Note 11] It is unclear when the iron rods or stone bound first appeared. At trial there was some explanatory but less than decisive testimony that other surveyors may have relied on the stone bound when conducting plans for other properties in the neighborhood.

34. In light of the surrounding registered land that conclusively establishes boundaries on either side of the subdivision, Toomey-Munson was correct to disregard the stone bound. Glover's approach is flawed - it essentially assumes its outcome and attempts to work backwards to justify it. Using the stone bound and iron rods shifts Glukhovsky's property lines to the west by at least ten feet to maintain the distances allotted on the Subdivision Plan. Leahy's property line with Lot 20 would have to shift to the west by the same amount. This leaves three possible outcomes, none of which are legally tenable: (1) shrink Leahy's lot by at least ten feet, (2) shrink corner Lot 20 by at least ten feet, or (3) maintain the lot sizes as depicted in the Subdivision Plan and instead extend the subdivision land into registered land, depicted on Plan No. 31022A, to the west by at least ten feet.

35. I conclude that the iron rods in the corners of Glukhovsky's property cannot be reconciled with the surrounding registered land and accordingly, Toomey-Munson and Rod Carter correctly disregarded both the stone bound and iron rods. I therefore find that substantial evidence supports Toomey-Munson's conclusion as to the precise location of the shared rear lot line and its two end points. Once this has been established, the court may proceed to a determination of the correct boundary line between the Leahy property and Glukhovsky property.

III. DISCUSSION

A. The Length of the Southern Boundary of the Subdivision

I refer to the legal principles which have guided me in drawing the findings and making the rulings in this case, and which instruct me on how best to deal with the final record title issue - how to assign the shortfall I conclude afflicts the dimension given on the Subdivision Plan for its southern line.

A dispute involving a common boundary line involves a question of fact to be determined on all the evidence. Hurlbert Rogers Machinery Co. v. Boston & Maine R. R., 235 Mass. 402 , 403 (1920). See Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 673 , 679 (2004). Where, as here, deed construction is a part of that analysis, the law provides:

... a hierarchy of priorities for interpreting descriptions in a deed. Descriptions that refer to monuments control over those that use courses and distances; descriptions that refer to courses and distances control over those that use area; and descriptions by area seldom are a controlling factor. Moreover, when abutter calls are used to describe property, the land of an adjoining property owner is considered to be a monument.

Paull v. Kelly, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 680 (internal citations omitted). Monuments, when verifiable, are thus the most significant evidence to be considered. When a "monument cannot be found and its location cannot be made certain by evidence," other descriptions control. Stoughton v. Schredni, 7 LCR 61 , 66 (1999)(Scheier, J.). After monuments, it is next courses and distances which control. Morse v. Chase, 305 Mass. 504 , 507 (1948). All of these rules of construction, however, "are not to be followed if they would lead to a result plainly inconsistent with the intent of the parties." Id. Where the described courses of a surveyed parcel are erroneous and "it is possible to rearrange them to conform to the bounds and the adjoining owners as described by the previous and subsequent deeds so that the description fits with the surrounding parcels," it is proper to do so. Ellis v. Wingate, 338 Mass. 481 , 485 (1959). See also W. ROBILLARD AND D. WILSON, BROWN'S BOUNDARY CONTROL AND LEGAL PRINCIPLES, 340 (6TH ED. 2009)("BROWN") ("If a description of land contains an error or mistake, and if the error or mistake can be isolated, the error or mistake is placed where it occurs.").

To determine the common boundary line between Leahy and Glukhovsky, I first must decide the correct length of the southern boundary of the subdivision. Based on the evidence above, I find that the rear lot line of the subdivision (its southern boundary) abuts the northern boundary of the English parcel. In 1930, this line was depicted as measuring 877.84 feet. See Exhibit 32. Although it appears on the Aspinwall plan, the northern boundary of the English parcel is not a registered line because the English parcel never had its title registered by this court. I further find that in 1953, when J.W. Semple first divided his land for development, the subdivision's southern boundary line was created and incorrectly depicted as 881.11 feet on the Subdivision Plan - a few feet longer than the northern boundary of the English parcel.

There is a 2.09 foot difference between the 1930 measurement of the northern boundary of the English parcel on the Aspinwall plan, which is 877.84 feet, and the 2007 Toomey-Munson measurement of the southern boundary of the subdivision on Exhibit 24, which is 875.75 feet. Although it remains unclear exactly how this discrepancy arose, there is at least one plausible explanation. This 2.09 foot difference is strikingly close to the 2.32 foot difference between the 1930 Aspinwall plan measurement of 82 "+/-" feet, on the one hand, see Exhibit 32, and the 1965 measurement of the same distance on Plan No. 31022A, on the other hand. The 1965 measurement was 79.68 feet. The 1966 registration of Plan No. 31022A could have shortened the 1954 subdivision's southern boundary by approximately two feet. This difference alone may account for the discrepancy and accordingly explain why the latest measurement of the southern boundary of the subdivision, conducted by Toomey-Munson in 2007, is 875.75 feet.

When Henry C. Meadow and Charles P. Lyman registered their property in 1961 in Registration Case No. 31022, the eastern boundary of their land abutted the western boundary of the English parcel, as well as Lot 20 of the subdivision (which abuts the English parcel to the north and Leahy's parcel to the east). The registration of the land depicted on Plan No. 31022A occurred over ten years after the creation of the subdivision. The in rem adjudication of the location on the ground of the Case 31022 parcel had the effect of conclusively settling the western boundary of the subdivision and fixing the length of the shared lot line of the subdivision and the English parcel - fixing its length at 875.75 feet, which Toomey-Munson found it to be in 2007. I accordingly conclude that in 1930, the northern boundary of the English parcel was reckoned at 877.84 feet; in 1953, the southern boundary of the subdivision, along the same line as the northern boundary of the English parcel, was incorrectly depicted on the Subdivision Plan as 881.11 feet; and in 1961, the registration of parcel 31022 set the southern boundary of the subdivision at 875.75 feet long.

No objection to the registration of the land depicted on Plan No. 31022A was made by a party claiming an interest in the subdivision land prior to the registration plan's approval by this court. Section 45 of G.L c. 185 provides that when the court "finds that the plaintiff has title proper for registration, a judgment of confirmation and registration shall be entered, which shall bind the land and quiet the title thereto." As described in Paragraph 11 above, Henry C. Meadow and Charles P. Lyman successfully petitioned for registration of their land west of the English parcel over forty years ago, and a decree of registration entered on April 26, 1966.

An adjudicated registration "shall be conclusive upon and against all persons, including the commonwealth, whether mentioned by name in the complaint, notice or citation, or included in the general description 'to all whom it may concern.'" G.L c. 185, § 45. A Notice of Filing Petition, included in Registration Case No. 31022, was recorded with the Registry on October 24, 1961 at Book 3938, Page 388. Included in the file of Registration Case No. 31022 are two return receipts of registered mail service in 1961 and 1963 to the Parkway Country Club, Inc., which owned the abutting English parcel at the time, thus providing notice of the pending registration case brought in Case No. 31022. There are similar return receipts of registered mail service to Jerome Hoffman in 1961 and 1963, whom Plan No. 31022A depicts as the owner of land abutting Parkway Country Club property to the north - land that is now Lot 20 on the Subdivision Plan. Finally, § 45 provides that a judgment for registration "shall not be opened by reason of the absence, infancy or other disability of any person affected thereby, nor by any proceeding at law or in equity for reversing judgments or decrees." [Note 12] The western boundary of both the English parcel and the southwestern corner of the subdivision was settled once this court decreed the registration of title in Case No. 31022 in 1966.

B. Deficiency Apportionment in the Southern Boundary of the Subdivision

Although I find that Toomey-Munson and Carter found the correct placement of the southeastern corner of the subdivision, and the southwestern bound is shown on a Land Court plan (31022), there was no express testimony at trial as to the distance between those two points. The Aspinwall plan shows the distance to be 877.84 feet. The Toomey-Munson plan states the line was calculated to be 875.75 feet, although there was no live testimony as to how that calculation was accomplished. Moreover, Carter did not adequately explain how his calculations account for the shortage in the rear lot line. Indeed, Carter did not consider the effect that a rear lot line of 875.75 feet would have on the widths of the five rectangular properties along the subdivision line, whose aggregate allotted widths - at least according to the Subdivision Plan - instead equal 881.11 feet. [Note 13]

Carter appears to use the Toomey-Munson monuments in his proposed plan, yet also uses the full Subdivision Plan distances. Simply put, the math does not add up. In his proposed plan, which is Exhibit 29, Carter uses distances taken from the Subdivision Plan for Lot 28, Lot 26, Lot 24, and Lot 22. Carter's proposed plan does not reflect a measurement for Lot 20, which is the subdivision's southeastern corner lot. The Subdivision Plan depicts 115 feet as the rear width of Lot 20. If Lot 20 had 115 feet on Exhibit 29, however, this would add up to a total of 881.11 feet - a number that exceeds the 875.75 feet measured by Toomey-Munson, and adopted by Carter, as the total distance of the rear lot line. If Carter used the Toomey-Munson calculation of the southern boundary line, Lot 20 could necessarily have only 109.64 feet. Based on Exhibit 29, Lots 28, 26, 24 (the Glukhovsky Property) and 22 (the Leahy Property) all would receive the distances allotted to them in the original Subdivision Plan, but Lot 20 would unilaterally suffer the shortfall, receiving only 109.64 feet. This result is untenable. There is no legal or equitable doctrine that would allow the court to apply a deficiency to one corner lot simply because the surveyor started his measurement from the other corner lot. Indeed, the rear lot line easily could have been measured beginning with Lot 20 - and by the same faulty logic, the owner of Lot 28 instead would be the unlucky one to bear the deficiency.

Once a determination is made that the allotted distances do not match the reality on the ground, courts must decide how to apportion the excess or deficiency of land. "The usual rule in Massachusetts, absent a plan, is that the excess land in a parcel if that were the problem or a deficiency if that is the case is gained or borne by the last grantee." Marsters v. Alden, Land Court Misc. Case No. 1312142 (August 21, 1990)(Sullivan, C.J.), 1990 WL 10093956 *5. The Marsters court quoted at length dicta from the Supreme Judicial Court's decision in Bloch v. Pfaff:

[W]hen an excess or deficiency is found to exist in the estimated distance between fixed monuments, divided into a given number of lots, a rule of apportionment is sometimes applied, which divides the difference between the several lots in proportion to the length of their respective lines. But this rule is only to be availed of when the land is conveyed by reference to a plan, or there is some declaration in the deed indicating a purpose to divide the land according to some definite proportion, and when there also is no other guide to determine the locations of the respective lots. Bloch v. Pfaff, 101 Mass. 535 , 538 (1869) (emphasis added). Other jurisdictions have held similarly. See, e.g., Adams v. Wilson, 137 Ala. 632, 634 (1903) ("Where a tract of land is subdivided, and is subsequently found to contain more or less than the aggregate amount called for in the surveys of the tracts within it, the proper course is to apportion the excess or deficiency among the several tracts") (quotations omitted); Hughes v. Yates, 222 Ark. 860, 863-864 (1958) (citing Bloch and Adams, supra); Condos v. Trap, 717 P.2d 827, 830 (Wyo. 1986) (there is a "general rule that a shortfall or excess in land in a tract should be divided equally among the grantees") (citing 12 Am. Jur. 2d, Boundaries, § 63 pp. 600-601). See also 1 PATTON AND PALOMAR ON LAND TITLES § 61 (3d ed.), n. 1 and cases cited ("When a tract of land is subdivided, and is thereafter found to be larger or smaller in any dimension than the aggregate of the tracts comprising it, as shown by the survey, the excess or deficiency generally is apportioned among its several component parts"); "Excess or deficiency existing in a straight line between fixed monuments within a subdivision is distributed among all the lots along the line in proportion to their record measurements." BROWN at 388.

The subdivision land in the case at bar was "conveyed by reference to a plan" (developed by J.W. Semple in 1953 and recorded in 1954). Bloch, supra at 538. See Paragraphs 2 and 3 above (describing the parties' deeds, both of which refer to the Subdivision Plan). The Subdivision Plan clearly indicates that each lot was to receive a defined allotment of land. Unfortunately, however, the "definite proportion" allotted according to the Subdivision Plan does not match the reality on the ground. The Subdivision Plan provides 881.11 feet for the shared rear lot line and, as Toomey-Munson discovered in 2007, there is only 875.75 feet between the eastern and western end points of that line. Because the shared rear boundary line of the subdivision does not actually have a distance of 881.11 feet - contrary to its depiction on the Subdivision Plan - I find it most equitable in the circumstances to conduct a proportional reduction, or proration, among all five parcels along the southern boundary of the subdivision. In using this methodology, as I conclude is just and fair and required by the controlling decisional law, to set the dividing line in dispute in this case - between the Leahy and Glukhovsky parcels--I do not render any binding adjudication as to the boundary lines of Lots 20, 26, or 28, whose owners are not parties in this litigation. I merely address what is necessary to determine the contested boundary between Lot 22 (the Leahy Property) and Lot 24 (the Glukhovsky Property). The boundary ruling in this case is limited to the determination of the single contested line between the Leahy Property and the Glukhovsky Property.

The difference between the distance set out on the Subdivision Plan and what Toomey-Munson measured [Note 14] is 5.36 feet. To determine the proportional reduction and calculate the precise location of the disputed boundary, it is necessary first to calculate what the percentage of the correct subdivision line, 875.75 feet, is out of the "record" length - that which the Subdivision Plan incorrectly provided for, 881.11 feet. I find that 875.75 feet is 99.3917 percent of 881.11 feet.

Next, to calculate the reduction in each of the five lots under a deficiency apportionment, it is necessary to multiply each lot's allotted width in the Subdivision Plan by the above percentage. Thus, I find that the width of Lot 20 would shift from 115 feet to 114.3004 feet, the widths of Lot 22 and 24 (which are the same) both would change from 150 feet to 149.0875 feet, the width of Lot 26 would alter from 161.76 feet to 160.7760 feet, and the width of Lot 28 would be not 304.35 feet, but instead 302.4986 feet.

Finally, to determine the correct location of the boundary line between Lot 22 and Lot 24, the task simply becomes a matter of adding the new widths of the subdivision lots together. Beginning in the west, adding the widths of Lot 20 (114.3004 feet) and Lot 22 (149.0875 feet) equals 263.3879 feet. Thus, the correct boundary between Lot 22 and 24 lies 263.3879 feet from the southwestern corner of the subdivision. Similarly, beginning in the east, adding the adjusted widths of Lot 28 (302.4986 feet), Lot 26 (160.7760 feet) and Lot 24 (149.0875 feet) yields 612.3621 feet. Therefore, the correct boundary between Lot 22 and Lot 24 also lies 612.3621 feet from the southeastern corner of the subdivision. Adding these distances confirms the total distance of the shared rear subdivision boundary of 875.75 feet.

C. Damages and Other Relief

Leahy requests treble damages for the willful girdling of trees on her property in violation of G.L. c. 242, § 7, as well as damages for the destruction of a stone wall, the deprived use of her property, and attorney's fees. This court has, in appropriate cases, jurisdiction to adjudicate claims of the sort Leahy advances under G.L. c. 242, § 7. See Ritter v. Bergmann, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 296 , 299 (2008) ("Nothing in G.L. c. 242, § 7, nor any other section of c. 242, for that matter, suggests that the Land Court does not have jurisdiction to consider claims under § 7, where other principles of law would permit such consideration").

Although Leahy "was not obliged to establish [. . .] damages with the exactness of mathematical demonstration," I find that Leahy failed to prove, or even introduce, any quantified amount of damages as a result of her alleged loss of trees. Bond Pharmacy, Inc. v. Cambridge, 338 Mass. 488 , 493 (1959) (no recovery based on conjecture; evidence must afford reasonable basis for measuring damage) (internal quotations omitted). Although Leahy cites Ritter in her request for treble damages, in that case the party whose trees were removed provided an expert witness to testify as to the "installed cost" and "wholesale price" of replacement trees, giving the judge a reasonable basis upon which to calculate fairly and accurately the amount of the damage. Ritter, supra at 307. Here there is no evidentiary basis to liquidate the compensable award to be made for the trees Leahy alleges Defendants or their agents destroyed, let alone a number this court might properly order tripled.

Essex v. Goldman arguably supports Leahy's contention that this court has the authority to hear her damages claim for the alleged destruction of a stone wall. See Essex Co. v. Goldman, 357 Mass. 427 , 434 (1970) ("Under G.L. c. 185, § 1(k) [. . .] the Land Court has jurisdiction of all matters of equity cognizable under the general principles of equity jurisprudence where any right, title or interest in land is involved [. . .] This jurisdiction may, in a proper case, include the award of damages") (internal quotations omitted). In Essex v. Goldman, however, the amount of damages essentially was set in the easement documents themselves; the covenant contained an annual rent obligation (to pay for mill power) that ran with the land. Essex, supra, at 432. The calculation of damages, therefore, required little additional evidence. Once the court determined that the "Goldmans were bound by the 1953 agreement," it followed that they were "obligated to pay the rent" provided in the agreement. Id. at 430. In contrast, any allegations of the destruction of a stone wall in the case at bar needed to have been supported by specific evidence, not present in the record, for the court to have a reasonable basis upon which to determine the actual costs of such damage. Cf. Ritter, supra at 307.

Whether or not this is a "proper case" in which the principle of Essex applies, however, I find and rule that Leahy failed to specify, with the requisite certainty in the evidence I credit, the amount of damages she seeks to recover for the lost use of her land or the destruction of a stone wall. Indeed, while Leahy did introduce some testimony and other evidence at trial concerning a disassembled stone wall along the disputed boundary line, [Note 15] the evidence, particularly as to the role of Glukhovsky and Keller in the wall's disturbance, was disputed by them, and I, as trier of fact, decline to find proof by a preponderance of the evidence that they bear culpability for damage to the wall. I also find Leahy has not provided a reasonable basis upon which this court could even begin to determine an award of damages with respect to any of the alleged injuries to her land. I conclude that Leahy's entitlement for damages is not supported by the record evidence I credit, and she did not carry her burden of proof.

What the parties are entitled to is a judgment setting the correct location on the ground of the disputed boundary line, as it has been fixed by this proceeding. To the extent that the fence or any other improvement erected by Defendants lies over the line so set, the judgment will require relocation or removal of whatever transgresses the boundary. [Note 16] The form by which the judgment is to address these points will be determined by the court after hearing from the parties, as discussed at the conclusion of this decision.

D. Adverse Possession

In their answer, Glukhovsky raised an affirmative defense of adverse possession regarding the land in dispute. Ostensibly, this alludes to a theory by the Defendants that, even if they invaded the land belonging of record to Leahy, they were not guilty of trespass because their complained of activities took place on land to which they had obtained title by the requisite acts of possession. "The burden of proving adverse possession is on the person claiming title" and at trial, the Defendants needed to have demonstrated "proof of nonpermissive use which is actual, open, exclusive, notorious, and adverse for twenty years." See Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003) (quoting Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 621-622 (1992) and cases cited). I find that Glukhovsky and Keller did not introduce, let alone prove, any evidence that could support this defense of adverse possession and so Glukhovsky and Keller did not satisfy their burden of proof in this regard.

E. G.L. c. 231, §6F.

Under G.L. c. 231, §6F, "[u]pon motion of any party in any civil action in which a ... decision .. has been made by a judge or justice ... the court may determine, after a hearing, as a separate and distinct finding, that all or substantially all of the claims, defenses, setoffs or counterclaims, whether of a factual, legal or mixed nature, made by any party who was represented by counsel during most or all of the proceeding, were wholly insubstantial, frivolous and not advanced in good faith. ... If such a finding is made... the court shall award to each party against whom such claims were asserted an amount representing the reasonable counsel fees and other costs and expenses incurred in defending against such claims...."

This is not a case in which the court could or would make the finding under this statute which Leahy seeks. First, I doubt whether the Defendants are parties who were "represented by counsel during most or all of the proceeding...." Although they had counsel during the initial months of this case, the bulk of the defense, including at trial, was carried out by the Defendants pro se, their lawyer having been permitted to withdraw in September of 2008 without objection from the Plaintiff.

More significantly, the title issues which the court confronted in deciding this case were complex and less than crisply lined up in the evidence. Neither side's theory of the case was outright adopted by the court in this decision, and the Plaintiff's requests for relief were in several respects insufficiently supported to merit entry of judgment in her favor. On this record, this is far from the type of case in which I would find that "all or substantially all" of the Defendants' claims and defenses "were wholly insubstantial, frivolous and not advanced in good faith." No finding or award under G.L. c. 231, §6F is available in this case.

IV. ENTRY OF JUDGMENT

Before judgment enters, I wish to afford the parties the opportunity to confer about the form the court's judgment should take, so as best to settle, of record, the disputed boundary determined by this decision. I will direct entry of a judgment which fixes that boundary according to the location of the corners of the southern line of the subdivision and the apportionment of the length deficiency along that line, as I have decided those two matters in this decision, unless I receive a proposal to prepare promptly for the court a more detailed plan, entirely consistent with this ruling and methodology. I understand the interest of the parties in having a plan in form suitable for recording in the Registry drawn up to settle with clarity their disputed boundary line. If the parties decline this opportunity, then judgment will enter which simply employs the deficiency apportionment laid out in this decision to describe the adjudicated line. I do encourage the parties to carry out this further measurement, and to have the line fixed on the ground in accordance with this decision; by doing so, the parties can determine whether and how much of an encroachment exists. If they concur that there is an encroachment, they can consider agreeing on how it ought to end.

I request Defendants and counsel for Plaintiff to confer, and, within thirty days, to submit to the court a joint written report setting out the parties' joint or several view(s) on these questions. If the parties agree that no new plan will be prepared, and no further confirming measurement will be made, they are with their report to submit one or two versions of the form the judgment ought to take. If there is a request for a new plan to be prepared, then the parties ought to advise the court in a comprehensive way how they would have the plan prepared--who will do the work and who will bear its expense, and how long it will take to finish and submit. I will respond to the report with appropriate instructions, without further hearing unless otherwise indicated, and then proceed to direct entry of an appropriate judgment.

Exhibit 1

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Toomey-Munson & Associates, a surveying firm previously employed by Plaintiff, went out of business in 2008. Leahy hired Rod Carter to review the firm's work and create a new plan in anticipation of this litigation.

[Note 2] This number is the sum of the rear lot widths of the five parcels on the subdivision plan: 115 feet, 150 feet, 150 feet, 161.76 feet, and 304.35 feet (from west to east).

[Note 3] The petitioner's plan is titled "Plan of Land in Canton, Scale 100 feet to an inch, November 18, 1922, Ernest W. Branch, Civil Engineer, 11 Adams Building, Quincy." This is the original plan that accompanied the filing of the registration petition with this court in 1922.

[Note 4] The Aspinwall plan is titled "Plan of Land in Canton - Mass. Scale 100 feet to an inch. January 8, 1930. Aspinwall & Lincoln, Civil Engr's. 46 Cornhill, Boston, Mass."

[Note 5] In 2011, the land registered in case no. 9125, excluding that shown on the 9125B plan, was withdrawn voluntarily from registration. See G.L. c. 185, s. 52. In light of the permanence of the adjudications made by this court when registering and confirming title under the Registration Act even following withdrawal from it pursuant to this statute, see id., this later event has no consequence for my decision in this case.

[Note 6] In surveying, iron rods also commonly are known as rebar, iron bar the construction industry primarily uses to reinforce concrete. Iron pipes, on the other hand, normally are hollow in the middle. Surveyors use both iron pipes and iron rods to mark boundary corners in the field.

[Note 7] Toomey-Munson & Associates found this iron pipe during surveys conducted in 2004 and 2007 and reached the same conclusion. Carter duplicated much of Toomey-Munson's work and relied heavily on their previous surveys.

[Note 8] This distance is the sum of the rear lot line widths of Lot 26 and Lot 28, which are 161.76 feet and 304.35 feet, respectively.

[Note 9] Notwithstanding this finding and ruling, which the court employs to decide the pending dispute between the parties, this court does not make any binding adjudication regarding the boundary lines of parties not before it.

[Note 10] The Toomey-Munson plan shows that an iron rod and a "ring of stones" were found north of this point, but no surveyor for any party has measured the distances from either to the iron pipe at the corner of the Subdivision at issue here.

[Note 11] Glover's testimony was unclear on whether, prior to measuring the property lines, Glukhovsky had shown him or told him about the iron rods that Glukhovsky believed marked his boundaries.

[Note 12] This bar against review is subject to limited exceptions, none of which are claimed by the parties or appear applicable here.

[Note 13] Mr. Carter recognized, in his testimony at trial, that such a deficiency generally would be "prorated" among the several affected parcels.

[Note 14] To the extent there is any doubt about the 875.75 foot figure, this may be and should be confirmed by having the parties' surveyors proceed in light of this decision to measure the distance between the two bounds at either end of the subdivision's southerly line, set as established in this Decision. The discussion that follows assumes an apportionment using the 875.75-foot figure, which I derive using the best evidence of the distance at trial. The Judgment that enters in this case will be without prejudice to such a confirmation, if indicated.

[Note 15] This evidence included testimony by Leahy and photographs of the rocks allegedly at issue. Glukhovsky, in unsworn statements to the court, and Keller, who testified, denied removing Leahy's stone wall.

[Note 16] What the judgment will not treat is any zoning (or similar land use law) status of improvements present on the parties' land which do not cross the boundary line. This case only concerns the property law rights of and between the parties. That the location of the line between the parties' two record title holdings, set by the court in this decision, may mean that structures on their parcels sit too close, as a matter of zoning law setbacks, to that line, is not an issue raised by this case or addressed by this decision.