ERIC FROST as trustee of Front Field Trust, EARL MALCOLM CONDON as trustee of the Earl Malcolm Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000, and MARY KAY CONDON as trustee of the Mary Kay Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000 v. BRUCE PERCELAY; SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN, BARRY RECTOR and FRANK SPRIGGS as members of the Nantucket Planning Board; and the TOWN OF NANTUCKET

ERIC FROST as trustee of Front Field Trust, EARL MALCOLM CONDON as trustee of the Earl Malcolm Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000, and MARY KAY CONDON as trustee of the Mary Kay Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000 v. BRUCE PERCELAY; SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN, BARRY RECTOR and FRANK SPRIGGS as members of the Nantucket Planning Board; and the TOWN OF NANTUCKET

MISC 08-379983

September 21, 2012

NANTUCKET, ss.

Long, J.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON PLAINTIFFS' MOTION FOR JUDGMENT ON THE PLEADINGS, DEFENDANTS' MOTION TO DISMISS THE COMPLAINT, AND PLAINTIFFS' MOTION TO AMEND THE AMENDED COMPLAINT

Introduction

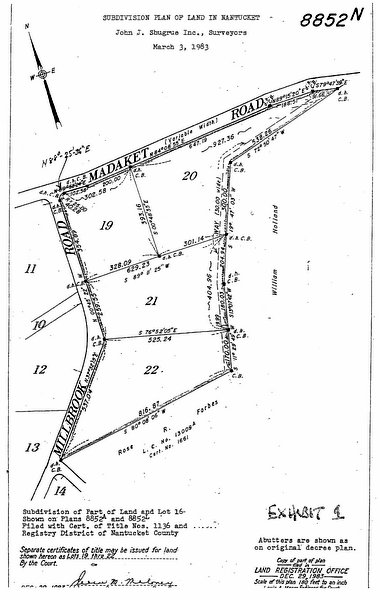

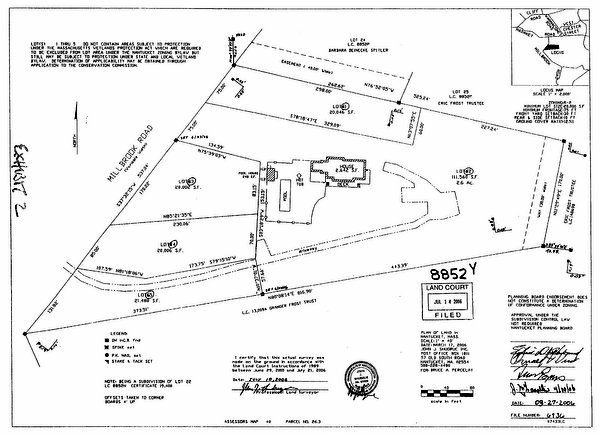

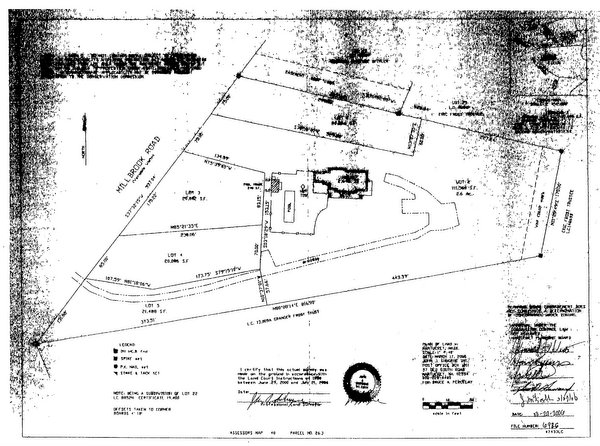

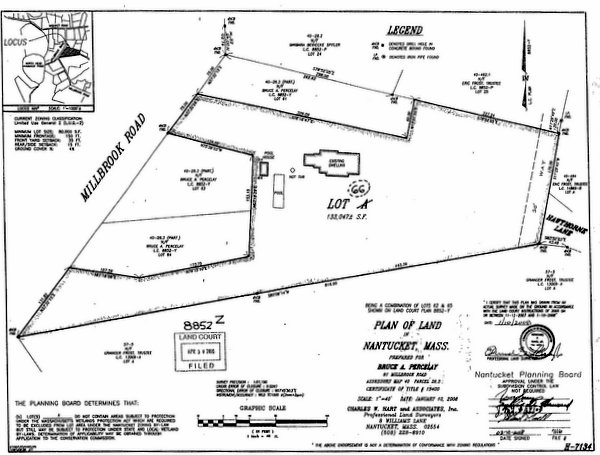

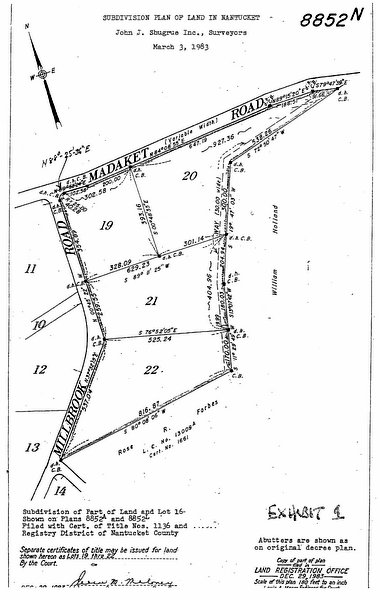

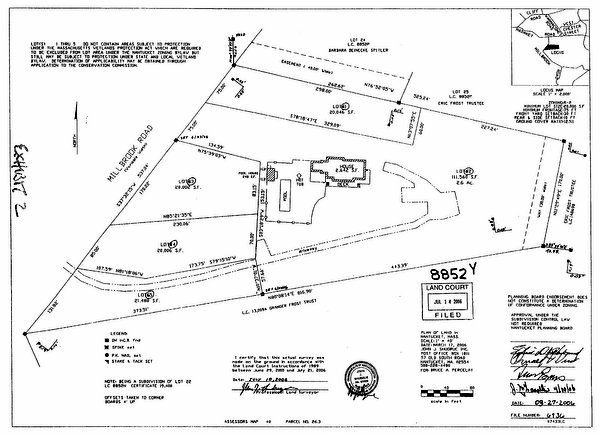

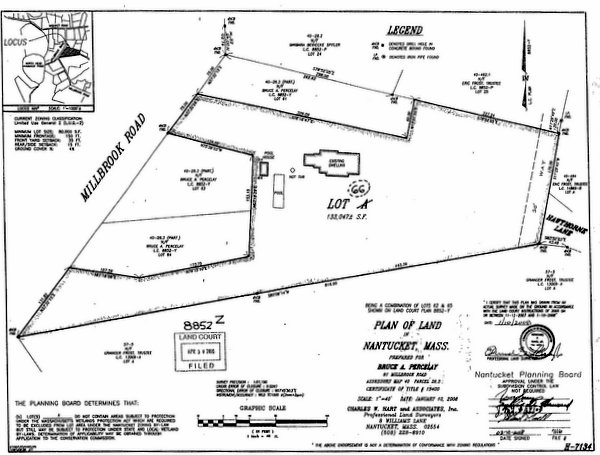

Defendant Bruce Percelay is the owner and part-time resident of the registered land at 81 Millbrook Road in Nantucket. Originally a single 3 ½ acre lot with a house, pool, and accessory structures (Lot 22 on Land Court Plan 8852N) (Exhibit 1, attached), it was divided into five lots (Lots 61-65) by an ANR plan [Note 1] endorsed by the Nantucket Planning Board on March 27, 2006 (the 2006 ANR Plan) (Exhibit 2) (Land Court Plan 8852Y). [Note 2] Lots 62 and 65 were subsequently combined and became Lot 66 on an ANR plan endorsed by the board on March 10, 2008 (the 2008 ANR Plan) (Exhibit 3) (Land Court Plan 8852Z). Lots 61, 63 and 64 were not changed by the 2008 plan and remained exactly as before. [Note 3] Combined Lot 66 contains the house and pool. Lots 61, 63 and 64 are currently undeveloped. Mr. Percelay continues to own each of the lots.

Plaintiff Eric Frost, as trustee, is the owner of two parcels that directly abut Mr. Percelays land and lives, part-time, on the one at 80 Madeket Road. Plaintiffs Earl Condon and Mary Kay Condon, as trustees, own and live part-time on land further down Madeket Road (No. 86), separated from Mr. Percelays property by an intervening lot.

Each of the plaintiffs is opposed to the development of the Percelay lots as configured in the ANR plans. Since challenges to the 2006 ANR plan are time-barred, see Stefanick v. Planning Bd. of Uxbridge, 39 Mass. App. Ct. 418 , 424 (1995); Murphy v. Planning Bd. of Hopkinton, 70 Mass. App. Ct. 385 , 389 (2007) (action must be commenced within 60 days after endorsement is granted), they have focused on the 2008 ANR Plan making, in essence, two arguments. The first, by Mr. Frost, is a contention that the ANR endorsement of the 2008 plan was arbitrary and capricious because, by his analysis, the lots lack sufficient frontage. Amended Complaint, Count I. The second, by all plaintiffs, is an assertion that the lots as shown on the plan are unbuildable because they are currently in an LUG-2 zone and do not comply with its dimensional and lot coverage requirements. Amended Complaint, Counts II-IV. [Note 4] I discuss each of these claims in turn.

Discussion

Plaintiff Frosts Challenge to the 2008 ANR Plan Endorsement

Judicial review of ANR endorsements is by certiorari, governed by the provisions of G.L. c. 249, § 4. [Note 5] Stefanick, 39 Mass. App. Ct. at 424; Murphy, 70 Mass. App. Ct. at 389. The reviewing judge is limited to what is contained in the record of proceedings below, [Note 6] Police Commr of Boston v. Robinson, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 767 , 770 (1999), and is not empowered to make a de novo determination of the facts. Durbin v. Bd. of Selectmen of Kingston, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 1 , 6 (2004). On certiorari review, a court will correct only a substantial error of law, evidenced by the record, which adversely affects a material right of the plaintiff. Conroy v. Conservation Commn of Lexington, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 552 , 558 (2009) (internal citations and quotations omitted). As applied to this case, the questions thus presented are whether the boards ANR endorsement of the 2008 plan was arbitrary or capricious, based upon error of law, or unsupported by substantial evidence and, if so, whether the consequences of that endorsement adversely affect plaintiff Eric Frosts property in a material way. Conroy, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 558. See also Fafard v. Conservation Commn of Reading, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 565 , 567 (1996). The analysis thus begins with an examination of what an ANR endorsement does and what it does not do.

A planning boards review of a plan submitted for ANR endorsement is limited to a single question. Does the plan show a subdivision as defined in G.L. c. 41, §81L? Endorsement must be granted if it does not. G.L. c. 41, §81P; Smalley v. Planning Bd. of Harwich, 10 Mass. App. Ct. 599 , 603-604 (1980); Long v. Bd. of Appeals of Falmouth, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 232 , 235-236 (1992); Bisson v. Planning Bd. of Dover, 43 Mass. App. Ct. 504 , 505-506 (1997). Whether the plan shows a subdivision is a two-part inquiry. First, it must show a division a tract of land divided into two or more lots. G.L. c. 41, §81L. Second, even if the plan shows such a division, it is not a subdivision within the statutory definition if each of the lots shown has sufficient frontage as required by the then-applicable zoning bylaw. Id. [Note 7]

ANR endorsements are typically sought for the freezes they provide. [Note 8] Two of the freezes are statutory: G.L. c. 40A, §6, sixth paragraph, and G.L. c. 40A, §6, fourth paragraph. Others may arise under particular town bylaws. With the exception of Nantucket Zoning Bylaw §139-33.F, which simply mirrors G.L. c. 40A, §6, fourth paragraph, no such Nantucket bylaws have been brought to my attention.

Under G.L. c. 40A, §6, sixth paragraph, when a plan referred to in section eighty-one P of chapter 41 [i.e., an ANR plan] has been submitted to a planning board and written notice of such submission has been given to the city or town clerk, the use of the land shown on said plan shall be governed by applicable provisions of the zoning ordinance or by-law in effect at the time of the submission of such plan

(emphasis added). This freeze remains in effect while such plan is being processed under the subdivision control law including the time required to pursue or await the determination of an appeal referred to in said section, and for a period of three years from the date of endorsement by the planning board that approval under the subdivision control law is not required, or words of similar effect. G.L. c. 40A, §6.

The sixth paragraph freeze is a limited one. It extends only to use (e.g. residential, industrial, multi-family, etc.), Bellows Farms Inc. v. Building Inspector of Acton, 364 Mass. 253 , 260 (1973) (freeze is limited to protection only against the elimination of or reduction in the kinds of uses which were permitted when the plan was submitted to the planning board), and only to the overall land shown on the plan, not the individual lots. Cicatelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Wakefield, 57 Mass. App. Ct. 799 , 803-805 (2003). It does not extend to any other requirements of the zoning bylaw or ordinance unless the impact of such changes, as a practical matter, were to nullify the use protection, Cape Ann Land Dev. Corp. v. Gloucester, 371 Mass. 19 , 22 (1976). [Note 9] In such cases, a reasonable accommodation with the dimensional regulations is made so the use can continue. Perry v. Bldg. Inspector of Nantucket, 4 Mass. App. Ct. 467 , 472 (1976). What constitutes a reasonable accommodation depends on the facts of the case. Id.

A second type of freeze, again limited, is available under G.L. c. 40A, §6, fourth paragraph, which provides:

Any increase in area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirement of a zoning ordinance or by-law shall not apply for a period of five years from its effective date or for five years after January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, whichever is later, to a lot for single and two family residential use, provided the plan for such lot was recorded or endorsed and such lot was held in common ownership with any adjoining land and conformed to the existing zoning requirements as of January first, nineteen hundred and seventy-six, and had less area, frontage, width, yard or depth requirements than the newly effective zoning requirements but contained at least seven thousand five hundred square feet of area and seventy-five feet of frontage, and provided that said five year period does not commence prior to January first, nineteen hundred and seventy six, and provided further that the provisions of this sentence shall not apply to more than three of such adjoining lots held in common ownership. The provisions of this paragraph shall not be construed to prohibit a lot being built upon, if at the time of the building, building upon such lot is not prohibited by the zoning ordinances or by-laws in effect in a city or town.

(emphasis added).

Zoning for the Percelay property changed on April 4, 2006. Previously in an R-2 District (minimum 20,000 square foot lot size; 75 frontage; 30 front setback; 10 rear and side setback; maximum 12.5% ground cover ratio), it was re-zoned into the LUG-2 District (80,000 square foot lot size; 150 frontage; 35 front setback; 15 rear and side setback; maximum 4% ground cover ratio) as of that date. As previously noted, the 2006 ANR Plan was endorsed by the planning board on March 27, 2006, before the zoning change became effective. [Note 10]

The plaintiffs are not materially affected by any sixth paragraph freeze at the present time. Zoning then, and zoning now, allows residential use on the Percelay land and, as noted above, the sixth paragraph freeze does not extend to the individual lots, only the entirety of the 3 ½ acre parcel. A residence already exists on the property and the overall parcel seemingly would satisfy either the R-2 or LUG-2 regulations for construction of a new residence even if one was not there now. Whether additional residences may be constructed on the individual lots and, if so, on which lots and subject to what dimensional regulations, is outside the scope of the sixth paragraph freeze.

Plaintiffs, however, may be affected by the fourth paragraph freeze should Mr. Percelay seek to construct additional residences on the individual lots. [Note 11] Here, assuming they meet the fourth paragraphs requirements, [Note 12] up to three of the lots have five-year protection [Note 13] from increased area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements for purposes of single family residential development. See Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 259-260 (2003) (the proviso does not exclude owners of four or more lots from the protection of §6 outright. It merely limits the number of lots for which any owner can obtain such protection). Lots that meet current zoning requirements have no need for such protection. [Note 14]

Mr. Frost disputes the applicability of these fourth paragraph protections because, he says, the 2008 ANR Plan was invalidly endorsed. But this is incorrect, for two reasons.

First, the 2006 ANR Plan is valid and continues to be valid; challenges are time-barred. See discussion, supra. While the 2008 ANR Plan superseded the 2006 Plan, it did not negate it. Under Land Court practice, as long as the lots remain in common ownership, Mr. Percelay can cancel the 2008 ANR Plan at any time, reverting to the lots shown on the 2006 Plan. [Note 15] See also G.L. c. 40A, §6 (submission of amended plan does not waive the provisions of §6). In any event, three of the lots were completely unchanged by the 2008 Plan (Lots 61, 63 and 64). The validity of their endorsement thus continues uninterrupted. [Note 16]

Second, as the board correctly noted, the 2008 ANR Plan does not show a division. Rather, it shows the continuation of three previously existing, previously endorsed lots and the combination of the two others. [Note 17] Thus, ANR endorsement was mandatory. G.L. c. 41, §81P; Smalley, 10 Mass. App. Ct. at 605 (if [the] plan does not create a subdivision within §81L, it is entitled to an endorsement

); Long, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 235-236; Bisson, 43 Mass. App. Ct. at 505-506. Mr. Frosts argument that zoning merger somehow negates this that the ANR lots merged for zoning purposes between 2006 and 2008 and thus were re-divided by the 2008 plan is wrong. G.L. c. 40A, §6, fourth paragraph, specifically grants a five-year residential-use freeze from greater area, frontage, width, yard, or depth requirements for up to three recorded or endorsed lots in common ownership at the relevant time. [Note 18] Whatever the applicability of the merger doctrine to other aspects of zoning, see Bisson, 43 Mass. App. Ct. at 507 (the endorsement of such a plan is a routine act, ministerial in character, and constitutes an attestation of compliance neither with zoning requirements nor subdivision conditions), merger does not apply to the three chosen lots for these requirements during the five-year freeze. Mr. Frosts certiorari challenge to the 2008 ANR plan thus fails because the plan does not show a division and because he is not harmed in any way not previously resulting from the 2006 ANR plan. That claim is thus DISMISSED.

The Request for Zoning Status Declaration

Counts II-IV request a declaration that the lots shown on the 2008 ANR plan are unbuildable because they currently are in an LUG-2 zone and do not comply with its dimensional and lot coverage requirements. Amended Complaint, Counts II-IV. [Note 19] The defendants have moved to dismiss those claims. The motion is ALLOWED.

The plaintiffs claim under G.L. c. 231A, §2 (Amended Complaint, Count III) fails because, at present, there is no actual controversy; Mr. Percelay has neither applied for nor received any building or other permits. See Mastriani v. Bldg Inspector of Monson, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 989 , 990 (1985) (no actual controversy prior to application for building permits or request to building inspector to take specific actions); Mass. Assoc. of Ind. Ins. Agents and Brokers v. Commr. of Ins., 373 Mass. 290 , 292-293 (1977); District Atty for Hampden Dist. v. Grucci, 384 Mass. 525 , 527 (1981). Count III is thus DISMISSED.

The plaintiffs claim under G.L. c. 185, §3A (Count IV) fails because that provision does not create any new causes of action, only subject matter jurisdiction in the Land Court to hear certain existing ones. Count IV is thus DISMISSED.

The plaintiffs claim under G.L. c. 240, §14A (Count II) requires somewhat more analysis. The statute reads as follows:

The owner of a freehold estate in possession of land may bring a petition in the land court against a city or town wherein such land is situated, which shall not be open to objection on the ground that a mere judgment, order or decree is sought, for determination as to the validity of a municipal ordinance, by-law or regulation, passed or adopted under the provisions of chapter forty A or under any special law relating to zoning, so called, which purports to restrict or limit the present or future use, enjoyment, improvement or development of such land or any part thereof, or of present or future structures thereon, including alterations or repairs, or for determination of the extent to which any such municipal ordinance, by-law or regulation affects a proposed use, enjoyment, improvement or development of such land by the erection, alteration or repair of structures thereon or otherwise as set forth in such petition. The right to file and prosecute such a petition shall not be affected by the fact that no permit or license to erect structures or to alter, improve or repair existing structures on such land has been applied for, nor by the fact that no architects plans or drawings for such erection, alteration, improvement or repair have been prepared. The court may make binding determinations of right interpreting such ordinances, by-laws or regulations whether any consequential judgment or relief is or could be claimed or not.

The primary purpose of proceedings under §14A is to determine how and with what rights and limitations the land of the person seeking an adjudication may be used under the provisions of a zoning enactment in terms applicable to it, particularly where there is no controversy and hence no basis for other declaratory relief. Harrison v. Braintree, 355 Mass. 651 , 654 (1969). The classic [§14A] case involves a landowner seeking a determination regarding his own land. Hansen & Donahue Inc. v. Town of Norwood, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 295 (2004). There, [t]he owner who may be contemplating a large investment on his land is thus provided with a thoroughly sensible means of ensuring that he is safe going ahead. Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. Inc. v. Reading, 354 Mass. 181 , 185 (1968). See also Whitinsville Retirement Society Inc. v. Northbridge, 394 Mass. 757 , 763 (1985). In such a case, as the statute provides, neither a building permit application nor final architects plans are a prerequisite to a §14A claim, thus avoiding their expense which might otherwise be for nought.

The scope of §14A is more limited in cases where the petition is not brought by a landowner planning development of his property, but instead by neighbors with concerns he may do so. In that situation, the neighbor may properly bring a §14A petition if, but only if, there would be a direct effect from a proposed development adverse to the use, enjoyment, improvement or development of that neighbors land. Harrison, 355 Mass. at 655. [Note 20] The feared use must be likely, not merely hypothetical or theoretical. See Hansen & Donahue, 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 296. [Note 21] And it must have a provable, adverse effect on the neighbors land. Fitch v. Bd. of Appeals of Concord, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 748 , 754 (2002).

Here it is not the owner, Mr. Percelay, who seeks a §14A determination of any type. He prefers to wait until such time, if ever, that his building plans crystallize and he submits specific applications for building permits. The question thus presented is whether the plaintiffs have a right to a §14A determination at the present time in the present circumstances. I conclude that they do not.

There are two types of cases that may properly be brought under §14A validity and extent. Banquer Realty Co. Inc. v. Acting Bldg. Commr of Boston, 389 Mass. 565 , 569-571 (1983). Validity cases, as the name suggests, concern the degree, if any, to which a local zoning provision is invalid or illegal. See, e.g., Sturges v. Chilmark, 380 Mass. 246 (1980) (questioning the validity of certain age and residency limitations in the bylaw). Extent cases seek determination of the extent to which particular zoning provisions affect a proposed use, generally a question of interpretation. Banquer Realty Co. Inc., 389 Mass. at 570-571.

Validity is not at issue in these proceedings. None of the towns bylaws are challenged in any way. Instead, the issue presented is one of extent as the plaintiffs phrase it, whether the Percelay lots are unbuildable because they are currently in an LUG-2 zone and (allegedly) do not comply with its dimensional and lot coverage requirements. But this phrasing is deceptively simple and highly misleading. What is actually involved in the answer to that question is a multi-part, lot-by-lot analysis, speculative and hypothetical. Mr. Percelay may not seek to take advantage of a freeze. He may not keep the lots in their present configuration at the time (if ever) he moves forward with development, [Note 22] either reverting to the 2006 Plan or making yet other and further changes. Even if he leaves the lots in their present configuration and takes advantage of the freeze, it is not at all clear which of the lots will be developed, [Note 23] how they will be developed, or what aspects of any applicable freeze may be involved. Thus, there may never be any true impact on the plaintiffs, much less a direct effect. Unlike Harrison which involved the validity of a bylaw, and Hansen which involved a general question of use applicable to all the property in question (whether it could be used for operation of an ambulance service), the declaration sought by plaintiffs is precisely the type of preemptive attack by abutters against theoretical uses which would unduly burden both land owners and the Land Court and thus falls outside the scope of §14A. [Note 24] See Hansen & Donahue Inc., 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 296. Count II is thus DISMISSED.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the plaintiffs claims are DISMISSED in their entirety. I need not and do not reach any of the defendants other arguments in support of their motion to dismiss. The plaintiffs motion to amend their amended complaint is DENIED since the allegations it seeks to add will not change the result. See Mathis v. Massachusetts Electric Co., 409 Mass. 256 , 264 (1991) (futility of amendment); Mancuso v. Kinchla, 60 Mass. App. Ct. 558 , 572 (2004) (same). Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

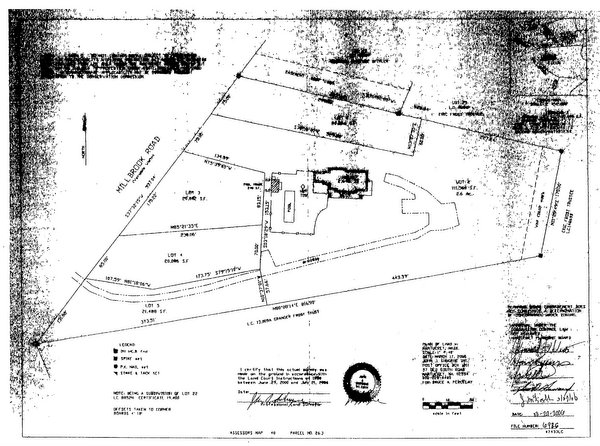

Exhibit 2A

Exhibit 3

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] ANR is shorthand for approval under the subdivision control law not required. The ANR process is relatively simple. Anyone who desires to record a plan of land in a city or town in which the subdivision control law (G.L. c. 41, §§ 81K-81GG) is in effect and believes that the plan qualifies for ANR treatment may submit it to the planning board of that city or town pursuant to G.L. c. 41, §81P. Cricones v. Planning Bd. of Dracut, 39 Mass. App. Ct. 264 , 266 (1995). A public hearing is unnecessary and ANR endorsement shall not be withheld unless such plan shows a subdivision. G.L. c. 41, §81P. Subdivision is defined as the division of a tract of land into two or more lots and shall include resubdivision

; provided, however, that the division of a tract of land into two or more lots shall not be deemed to constitute a subdivision within the meaning of the subdivision control law if, at the time when it is made, every lot within the tract so divided has frontage on (a) a public way or a way which the clerk of the city or town certifies is maintained and used as a public way, or (b) a way shown on a plan theretofore approved and endorsed in accordance with the subdivision control law, or (c) a way in existence when the subdivision control law became effective in the city or town in which the land lies, having, in the opinion of the planning board, sufficient width, suitable grades and adequate construction to provide for the needs of vehicular traffic in relation to the proposed use of the land abutting thereon or served thereby, and for the installation of municipal services to serve such land and the buildings erected or to be erected thereon. Such frontage shall be of at least such distance as is then required by zoning or other ordinance or by-law, if any, of said city or town for erection of a building on such lot, and if no distance is so required, such frontage shall be of at least twenty feet. G.L. c. 41, §81L.

[Note 2] The plaintiffs argue that the endorsement did not become effective until April 10, 2006, the date planning board member John McLaughlin signed Land Court Plan 8852Y (the date has significance because zoning changed on April 4, 2006 as a result of Town Meeting vote, see discussion below). But they are incorrect. The Supplemental Certified Record shows that endorsement was granted by unanimous vote of the board at its March 27, 2006 meeting (see Meeting Minutes), the Endorsement Date was March 27, 2006 (ANR Application Form at 2), and the originally-endorsed plan (8852Y is the same plan, with the additional information and lot numbers required for registration) was signed by all five voting members, including Mr. McLaughlin, on March 27, 2006. See Ex. 2A.

[Note 3] As characterized by Nantuckets Land Use Planner in connection with his recommendation to the planning board that the 2008 plan be given ANR endorsement (a recommendation the board accepted), the applicant is creating only one new lot with three parts left over as shown on a land court plan #8852-Y as Lots 61, 63 and 64. Memo from Tom Broadrick, Nantucket Land Use Planner, to Planning Board, Re: Agenda Items for 3/10/08 at 3 (Mar. 4, 2008). In short, in the view of the board and its staff, the 2008 plan showed a combination, not a division. See n. 1, supra.

[Note 4] A third contention, that the further development of the lots would violate an alleged deed restriction limiting their combined use to only one single family dwelling house together with attendant out-buildings, is neither ripe nor presented in these proceedings. To date, only one single family house and its accessory buildings exist on the property, and Mr. Percelay has neither sought nor obtained a building permit for anything else.

[Note 5] In relevant part, G.L. c. 249, §4 provides:

A civil action in the nature of certiorari to correct errors in proceedings which are not according to the course of the common law, which proceedings are not otherwise reviewable by motion or by appeal, may be brought in the supreme judicial or superior court or, if the matter involves any right, title or interest in land, or arises under or involves the subdivision control law, the zoning act or municipal zoning, or subdivision ordinances, by-laws or regulations, in the land court or, if the matter involves fence viewers, in the district court. Such action shall be commenced within sixty days next after the proceedings complained of.

The court may enter judgment quashing or affirming such proceedings or such other judgment as justice may require.

[Note 6] The contents of the record have previously been determined by this court. Memorandum and Order on Plaintiffs Motion to Supplement the Certified Record of Proceedings (Feb. 25, 2009).

[Note 7] The frontage must be on one of the three types of ways defined in G.L. c. 41, §81L. See n. 1. If the zoning bylaw or ordinance does not have its own frontage requirement, the statute requires at least twenty feet. G.L. c. 41, §81L.

[Note 8] There are also other reasons. As the case law notes, even a plan showing zoning violations can serve many legitimate purposes. [It] may be preliminary to an attempt to obtain a variance, or to buy abutting land which would bring the lot into compliance, or even to sell the non-conforming lot to an abutter and in that way bring it into compliance. Smalley, 10 Mass. App. Ct. at 604.

[Note 9] Such so-called de facto use regulations are rarely found. A dimensional regulation amounts to a de facto use regulation if its impact as a practical matter eliminates or virtually nullifies a protected use. Cicatelli, 57 Mass. App. Ct. at 801. Short of that, a municipality may impose reasonable conditions which do not amount, individually or collectively, to a practical prohibition of the use. Cape Ann Land Dev. Co., 371 Mass. at 24. See Bellows, 364 Mass. at 260-261 (affirming right of municipality to subsequently impose requirements that had the effect of reducing the number of apartment units which could be built on the land at issue but that did not constitute or otherwise amount to a total or virtual prohibition of the use of the locus for apartment units or impede the reasonable use of plaintiffs land for apartment unit purposes, notwithstanding the reduced number of units permitted under the by-law as amended).

[Note 10] See n. 2, supra.

[Note 11] Whether there will be any actual effect and, if so, to what degree, depends on what (if anything) Mr. Percelay or his successors propose to build, where they propose to build it, and whether any aspect is in any way dependent on the freeze. All this is speculative at this point a circumstance I discuss in more detail below.

[Note 12] The deed restriction issue is a separate question, not presented in this proceeding.

[Note 13] Measured from March 27, 2006. See discussion below. Again, the five-year period is tolled during the pendency of litigation. Because the effectiveness of the 2006 ANR Plan is at issue in this lawsuit, the tolling applies.

[Note 14] As discussed more fully below, I need not and do not decide if any of the lots shown on the 2008 ANR plan meet all of the current zoning requirements, although it appears none do. Only Lot 66 has sufficient square footage, but it is doubtful it meets the current frontage requirement. The present bylaw appears to require 150 continuous feet of frontage, defined as the lineal extent of the boundary between a lot and an abutting street measured along a single street line

, Bylaw §139-2 (emphasis added), thus precluding the aggregation of discontinuous sections. Lot 66 does not have 150 feet of continuous frontage, only two widely-separated sections each below the 150 minimum.

Likewise, for the reasons discussed below, I need not and do not decide if any of the lots shown on the 2006 ANR plan met all then-applicable zoning requirements, although the boards ANR endorsement indicated they had sufficient frontage at that time.

[Note 15] As a technical matter, the Land Court surveying department would require the submission of a new plan and give it the next sequential number to keep the sequence going forward. It would then immediately be approved if it was precisely the same as the Y plan.

[Note 16] The corollary to this is obvious. Because their validity dates to the 2006 Plan, the five-year freeze dates from the time of the 2006 plan, tolled during the pendency of this lawsuit. An applicant cannot re-set the freeze simply by filing a new plan showing the identical lots. See G.L. c. 40A, §6 (submission of amended plan does not further extend the applicability of the ordinance or bylaw that was extended by the original submission).

[Note 17] See n. 3, supra.

[Note 18] Subsequent conveyance of the lots does not take away the protection. Lots held in common ownership at the effective date of a zoning change are grandfathered under the common ownership provision of §6, and remain grandfathered for five years whether or not they remain in common ownership at the time of a subsequent building permit application. Marinelli, 440 Mass. at 261.

[Note 19] Count V is a request for judicial endorsement of a memorandum of lis pendens (a remedy), and does not state a substantive cause of action.

[Note 20] See also Fitch v. Bd. of Appeals of Concord, 55 Mass. App. Ct. 748 , 753-754 (2002) (A landowner may also petition under §14A concerning land other than his own in the limited circumstances where the proposed use on that other land has a direct effect on his).

[Note 21] See also Fitch, 55 Mass. App. Ct. at 753 n. 7 where the court noted, [t]his is not a case of a landowner being compelled to defend a hypothetical right to build. It was [the landowner] who triggered the controversy by applying for and obtaining a building permit; Hansen & Donahue, where the ambulance service being challenged had actually been in operation: Harrison, where the zoning amendment allowed industrial access over neighboring residential parcels; and Mastriani, 19 Mass. App. Ct. at 989-990, where zoning was changed from rural residential to general commercial to allow construction of a medical office building.

[Note 22] He has already combined two of the 2006 lots in his 2008 plan.

[Note 23] Recall that only three can use the fourth paragraph freeze, and only if their development occurs within the freeze period.

[Note 24] The plaintiffs affidavit by Eric Frost (Apr. 30, 2009) attempts to show such direct effect but fails since it is based on hypothetical development scenarios (all lots developed, with two houses per lot) which may never come to pass and are not currently planned. It is also unclear if many of the impacts he posits (impairment of views across open land; effect on the rural character of the area; etc.) are protected under the zoning bylaw in the ways he asserts.

ERIC FROST as trustee of Front Field Trust, EARL MALCOLM CONDON as trustee of the Earl Malcolm Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000, and MARY KAY CONDON as trustee of the Mary Kay Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000 v. BRUCE PERCELAY; SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN, BARRY RECTOR and FRANK SPRIGGS as members of the Nantucket Planning Board; and the TOWN OF NANTUCKET

ERIC FROST as trustee of Front Field Trust, EARL MALCOLM CONDON as trustee of the Earl Malcolm Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000, and MARY KAY CONDON as trustee of the Mary Kay Condon Revocable Living Trust Agreement dated August 17, 2000 v. BRUCE PERCELAY; SYLVIA HOWARD, NATHANIEL LOWELL, JOHN McLAUGHLIN, BARRY RECTOR and FRANK SPRIGGS as members of the Nantucket Planning Board; and the TOWN OF NANTUCKET