WULF PAULICK and RENATE PAULICK v. WELLFLEET CONSERVATION TRUST, TOWN OF WELLFLEET and the COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

WULF PAULICK and RENATE PAULICK v. WELLFLEET CONSERVATION TRUST, TOWN OF WELLFLEET and the COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

REG 04-43391

October 24, 2012

BARNSTABLE, ss.

Long, J.

DECISION

With:

- SBQ 02-43038 : ROBERT EISINGER and MIRIAM EISINGER v. WELLFLEET CONSERVATION TRUST, TOWN OF WELLFLEET and the COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

Introduction

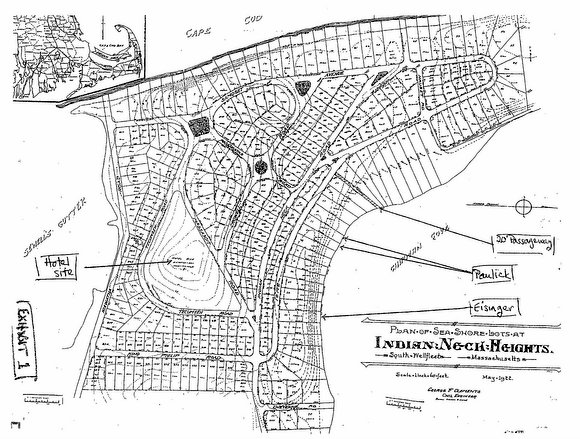

Petitioners Wulf and Renate Paulick (Case No. 04 REG. 43991 (KCL)) and Petitioner Miriam Eisinger (Case No. 02 SBQ 43038 (KCL)) own property along Chipmans Cove in Wellfleet. Both properties are part of the Indian Neck Heights subdivision laid out by M. Burton Baker in May 1922. See Subdivision Plan (Ex. 1, attached). The Paulicks own Lots 57 and 58 as shown on that plan. Both lots are presently recorded land. Ms. Eisinger owns Lot 66, the title to which is registered.

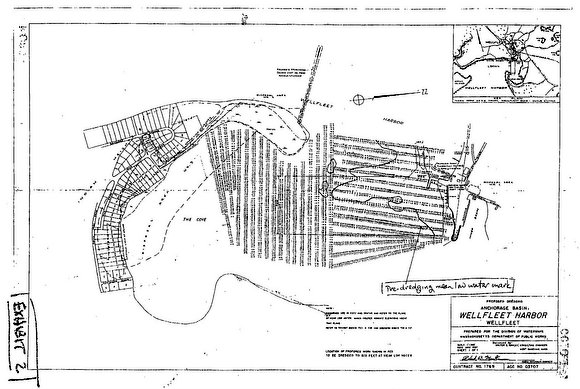

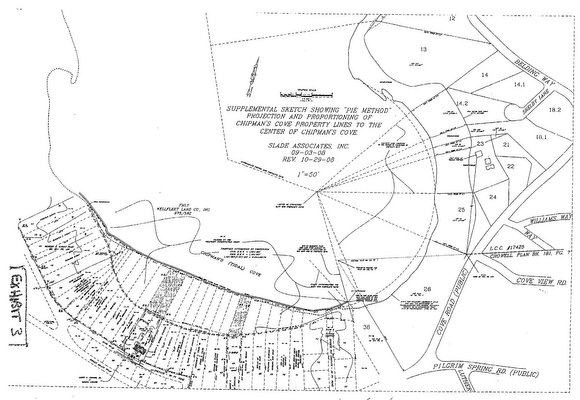

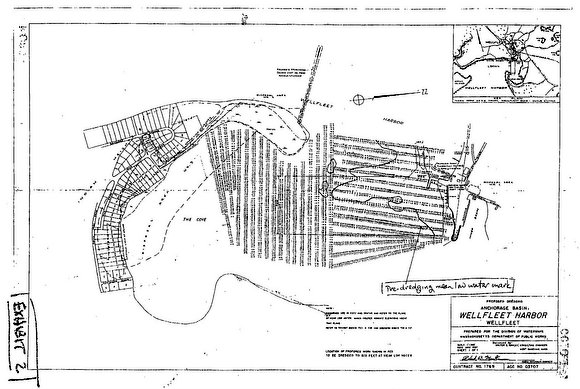

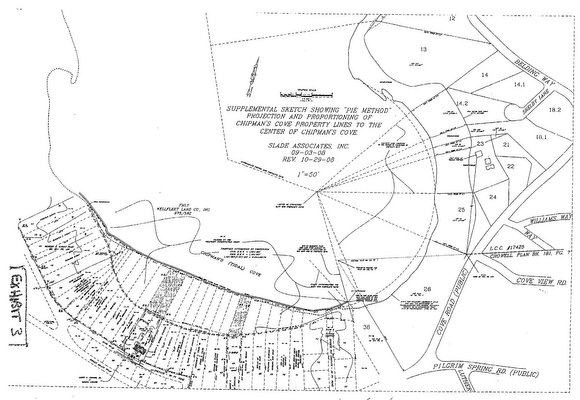

Shorefront property involves two types of land, upland (the area above the mean high water mark) and flats (the area between the mean low water and mean high water marks), sometimes called the beach or shore. [Note 4] See Storer v. Freeman, 6 Mass. 435 , 439 (1810); Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 828-829 (2008). Chipmans Cove is the southern end of Wellfleets inner harbor. The harbors channel and anchorage basin were dredged in 1957 and much of the spoils dumped in the Cove. See Ex. 2 (dredging plan). The result was the accretion of additional upland and flats along the former waters edge, including the areas in front of the Paulick and Eisinger properties. See Exhibit 3. [Note 5]

Case No. 04 REG 43391 (KCL) is the Paulicks petition to register title to their land out to the historic low water mark, defined as the mean low water mark as it existed pre-dredging. See Stipulation between Petitioners and the Commonwealth at 2 (Sept. 9, 2010) (Paulick Stipulation) (stating that the petitioners are not claiming any interest in submerged lands below the historic low water mark). In other words, they seek title to the original (pre-dredging) upland on their lot, the post-dredging upland, and the pre-dredging flats. [Note 6] That petition is based on two propositions. The first is the doctrine that, unless the two have been severed, the owner of an upland parcel also owns the adjoining flats as far out as the mean low water line or 100 rods (1650 feet) from the mean high water line, whichever is less. See Opinion of the Justices, 365 Mass. 681 , 685 (1974); Mayhew v. Norton, 34 Mass. (17 Pick.) 357, 360 (1835). The second is the principle that, when the boundary between the water and the land changes by the gradual deposit of sand and clay and the like, then the line of ownership ordinarily follows the changing water line. Lorusso v. Acapesket Improvement Assn, 408 Mass. 772 , 780 (1990). This also applies to accretions, as here, that are the incidental result of the dumping of dredge spoils. Id. [Note 7]

It is undisputed that the Paulicks own the pre-accretion upland on Lots 57 and 58. They contend that the flats were never severed. Based on their ownership of this upland and their alleged ownership of the pre-accretion flats, they thus claim ownership of all the accretions resulting from the 1957 dredging and associated spoil dumping, both upland and flats, as far as the pre-dredging mean low water mark. Since the accreted land is along a cove, ownership is determined by the doctrine of equitable division, giving each owner the same proportion of the new waterfront he would have had if the accretions had never occurred. Lorusso, 408 Mass. at 780-81. Those ownership lines as far as the current mean high water mark (i.e. as far as the upland presently extends) are shown on Exhibit 3. [Note 8]

Case No. 02 SBQ 43038 (KCL) is Ms. Eisingers S-petition seeking to extend her registered title to Lot 66 to the pre-dredging mean low water mark based on the same propositions as asserted by the Paulicks. [Note 9] It is undisputed that Ms. Eisinger is the owner of the pre-accretion upland. Indeed, her registered title includes this area. [Note 10] Ms. Eisinger asserts that the flats were never severed. Thus, like the Paulicks, she claims ownership of the former upland, the new upland, and the flats out to the pre-dredging mean low water mark.

Defendant Wellfleet Conservation Trust opposes these petitions insofar as they seek to register title in the petitioners to anything beyond the mean high water mark as it existed pre-accretion. The Trust bases this opposition on its contention that the pre-accretion flats were severed from each of those lots and those flats subsequently conveyed to the Trust. [Note 11] It thus claims ownership of all accretions, both upland and flats.

Two questions are thus presented. Both are questions of fact. First, were the flats severed? This is a matter of discerning the intent of the grantor. Pazolt v. Dir. of the Div. of Marine Fisheries, 417 Mass. 565 , 570-71 (1994) (presumption that flats follow the upland may be overcome by proof of contrary intent); Lebel v. Nelson, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 300 , 303 (1990) (holding that proof of title in the upland carries with it title to the flats unless there is evidence from which an affirmative intent to separate the two may be inferred); Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct.at 830 (intent to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in light of the attendant circumstances). Second, if the flats were severed, exactly what was severed? This is also a matter of the grantors intent. Id. Was a fixed boundary intended so that all subsequent accretions, upland and flats alike, would accrue to the owner of the flats? Or was a so-called movable boundary intended so that newly accreted upland would belong to the owner of the former upland and newly accreted flats would belong to the owner of the former flats? See Scratton v. Brown, 107 Eng. Rep. 1140, 1146-1147, 4 Barn. & Cress. 485, 498-499 (K.B. 1825)) (discussing moveable freeholds and observing, [t]he Crown by a grant of the sea-shore would convey, not that which at the time of the grant is between the high and low-water marks, but that which from time to time shall be between these two termini. Where the grantee has a freehold in that which the Crown grants, his freehold shifts as the sea recedes or encroaches

.[W]ith reference to the rule of the common law upon the subject of accretion

as the high and low-water marks shift, the property conveyed by the deed also shifts.); Percival v. Chase, 182 Mass. 371 , 378 (1903) (citing Scratton) (Where a grantor owning the shore to low water conveys the shore between high and low water, the boundary line between the highland retained by him and the shore conveyed away is a movable one and changes as the sea recedes from or encroaches on the land); Phillips v. Rhodes, 48 Mass. 322 ( 7 Met. 322 ), 325 (1843) (parties well knew the shifting nature of the beach at the time of making the conveyance

[A]s the privilege was to take the sea dressing on the beach below the home field, the right cannot be affected by the gradual and imperceptible changes taking place on the sea-shore. Wherever the beach exists in front of or below the field, there the right of taking the sea dressing extends, and it matters not whether the sea has gained upon the land or has receded. The beach remains, and to that the easement is appurtenant).

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. I also took a view. Based on the totality of the evidence, for the reasons set forth below, I find and rule that the flats were severed, but that what was severed was the flats wherever they might be at any given time. Thus, the petitioners have registrable title to the accreted upland associated with their lots, out to the current mean high water mark, in accordance with the lines shown on Exhibit 3. Since these registration petitions concern only the petitioners titles, not anyone elses, I need not and do not decide if the Wellfleet Conservation Trust owns the flats beyond that mark only that the petitioners do not. Finally, I find and rule that the areas of pre-accretion and post-accretion flats within the land registered in these cases are subject to the publics rights as set forth in the Stipulations. [Note 12] See Arno v. Commonwealth, 457 Mass. 434 , 436 (2010) (the public has certain rights in all tidelands); Moot v. Dept. of Environmental Protection, 448 Mass. 340 , 342 (2007) (Under the public trust doctrine, the Commonwealth holds tidelands in trust for the use of the public for, traditionally, fishing, fowling, and navigation). Judgment shall enter accordingly.

Facts and Analysis

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

By deed dated December 10, 1921, M. Burton Baker (Mr. Baker) acquired a large tract of land in Wellfleet bordered on the west by the shore of Cape Cod Bay and on the north by the channel of a cove (Chipmans Cove). [Note 13] The land included both the upland and the flats along those bodies of water. He named it Indian Neck Heights and laid out 282 lots as shown on his subdivision plan. Ex. 1. Fifty-nine of those lots are along the waterfront -- thirty on Cape Cod Bay and twenty-nine on Chipmans Cove.

From 1922 to 1933, Mr. Baker deeded out twenty-eight of the Bay-side shorefront lots and five of the shorefront lots on the Cove-side. The water-side of each was described as by the bottom of the bank. One of these Cove-side lots was Lot 57, which Mr. Baker conveyed to the Paulicks predecessor in 1931. [Note 14] The conveyance of Lot 57 described it as lot numbered 57 on said plan (Ex. 1), with side and waterside boundaries as running northwesterly by lot 56 one hundred seventy-two and 50/100 (172.50) feet to a bound and bottom of the bank on Indian Neck Cove, [Note 15] thence easterly by the bottom of the bank on said Cove fifty two and 50/100 (52.50) feet to a bound and lot 58, thence southwesterly by lot 58 one hundred seventy two and 50/100 (172.50) feet to a bound and north line of Ione Road

[Note 16] Four things are noteworthy. First, the land conveyed is described by reference to the 1922 subdivision plan (Ex. 1). That plan shows the sea-ward boundary of the lot as the mean high water line (i.e. the edge of the upland). It also shows a twenty-foot wide public passageway from the street to the Cove not far away, indicative of an intent to reserve the beach for general community access. Second, the land conveyed is described as running to the bottom of the bank and by the bottom of the bank, not to or by the channel of [the] cove (the sea-ward limit of Mr. Bakers property as described in his deed from Luther Crowell). This again is indicative of a knowing intention to sever the beach. See testimony of Chandler Crowell that the water [pre-dredging] came up

to the bottom of the bankings and in front of the houses along the edge of the cove. Transcript at 50 (Sept. 9, 2010) (showing that the bottom of the bank and the mean high water mark on the Cove-side were essentially visually the same prior to commencement of the dredging). See also Castor v. Smith, 211 Mass. 473 , 474 (1912) (boundary described in deed as by the upper edge of the beach which the court held meant that a severance had occurred, the court observing, [u]nless terms occur in the deed indicating a different intent, a conveyance of land describing the beach as its boundary does not include the beach, but extends to the line of mean high water). Third, although sideline measurements are given in the deed description and are shorter than the measurements shown on the plan, they were likely measured either to the bounds referenced in the deed [Note 17] or some other presently unmarked location rather than the end of the lot at the high water mark. [Note 18] Fourth, the flats extended nearly to the town pier and boat ramp at the entrance to the inner harbor (see Ex. 2) and apparently were used as a common area for Cove residents to anchor their boats. See Transcript at 50-51 (testimony of Chandler Crowell). In sum, I conclude (and so find) that Mr. Baker intended to sever the flats from the upland when he conveyed Lot 57.

Further, particularly in light of his use of the bottom of the bank as the boundary of the lot, I conclude (and so find) that what he intended to convey was a movable boundary: the boundary of the lot would remain the bottom of the bank (the mean high water mark) wherever it might be, and the severed flats would only contain flats. This is consistent with the subdivision plan (showing the shorefront lot boundaries as the high water line, a boundary that moves over time as the shore shifts) and his obvious intent of reserving the beach for community use while protecting the integrity and privacy of the homes along the bank and the attractiveness of those lots to potential customers. The shorefront lots were small. It is one thing to have the residents of 282 house lots (and potentially a hotel) on the flats below the shorefront homes. It is quite another to have them at a higher elevation (on accreted upland) and thus effectively in the immediate back yards of those homes surely something neither Mr. Baker nor his shorefront grantees expected or intended.

In 1933, Mr. Baker conveyed all of his remaining land in the subdivision (everything he had not previously conveyed) to his son Kenneth and Kenneths wife Hilda, describing the sea-ward boundary exactly as it had been described in Mr. Bakers deed from Luther Crowell (i.e. by the channel of a cove). [Note 19] Kenneth and Hilda Baker subsequently conveyed two shore-side lots to individual purchasers, one describing its sea-ward boundary as by bottom of bank [Note 20] and the second by the foot of the bank. [Note 21] After Kenneths death, Hilda conveyed various Cove-side shore lots, all by reference to the subdivision plan (Ex. 1). [Note 22] In 1949, Hilda conveyed title to all her remaining property in the subdivision to Dorothy Snow (Ms. Snow), describing its sea-ward boundary as the channel of a cove and by said channel, [Note 23] showing (1) she knew how to describe the flats when she wanted to, and (2) by not using this description, she had not included the flats in her previous deeds of individual Cove-side shore-front lots. This remaining property included Lot 66 (the current Eisinger land), Lot 58 (now part of the Paulicks property), and all of the flats along the Cove.

In 1955, Ms. Snow conveyed lot 66 to Ms. Eisingers predecessor, describing it as being Lot #66 on [the subdivision plan (Exhibit 1)], and its side and waterside boundaries as running Northerly by Lot #65, 220 feet more or less to the high water line; thence turning and running Easterly by the high water line, 60 feet more or less to Lot # 67; thence turning and running Southerly by Lot #67, 223 feet more or less to the point begun at. [Note 24] For much the same reasons as my analysis of Mr. Bakers conveyance of Lot 57, I conclude (and so find) that Ms. Snow intended to sever the flats from the upland, and that she intended a moveable boundary. First, she conveyed the lot with reference to the subdivision plan. As previously noted, that subdivision plan shows (1) the lot boundary as the mean high water mark, and (2) community access to the beach (the 20 foot passage previously referenced to the West, and Cheyenne Road to the East). Second, the deed language gives the sea-ward boundary of the lot as to the high water line and by the high water line, showing exclusionary intent for the flats. See Castor, 211 Mass. at 474. And the sideline measurements correspond to those shown on the subdivision plan, out to the then- (pre-dredging) high water mark as shown on the plan. Third, Ms. Snow clearly believed she retained title to the flats as shown by her subsequent conveyance of all [her] right, title and interest

in and to the shore and flats in the nature of riparian rights in the property adjoining the development known as Indian Neck Heights to the Wellfleet Land Co. This was identified in that deed as the area from the easterly line of Lot 75 to the northerly line of Lot 36 (i.e. the entirety of the subdivisions Cove-side shore). [Note 25]

I also conclude (and so find) that Ms. Snow intended a moveable boundary in which accreted upland would accrue to the owner of the pre-accretion upland, and the pre-accretion owner of the flats would continue to own only flats, for the following reasons. First, the deed language conveying the lot as shown on the subdivision plan shows so. The sea-ward boundary on that plan is the high water line -- a line that moves as the shoreline changes over time. Second, it followed the pattern previously set by Mr. Baker and his son and daughter in law, Kenneth and Hilda Baker (reserving the flats, but only the flats, for general access). Third, it preserved the integrity and privacy of the lots she was selling clearly of importance to the purchasers of those lots. See discussion above. Fourth, her subsequent deed of the shore and flats to the Wellfleet Land Co. referenced only the shore and flats. It did not reference any upland or soon- to-be accreted upland. The plans to dredge Wellfleet Harbor were already well advanced by the time of this conveyance (May 1957 the final dredging plan came out in June) with the certainty of significant accretions to the Cove. Surely Ms. Snows deed to the Wellfleet Land Co. would have referenced upland accretions had she believed they were contained in her conveyance. Fifth, the accreted upland on Lot 66 has already been included in Ms. Eisingers registered title by the Decree and Judgment entered by this court in 1999. As noted above, the Registration Decree describes Ms. Eisingers northerly boundary as by Chipmans Cove, determined by the court to be located as shown on a plan drawn by William N. Rogers, Surveyor, dated November, 1993, as modified and approved by the court. That plan shows the northerly boundary as by the November 10, 1993 (i.e. post-accretion) mean high water mark. Decree Plan (Jun. 8, 1999, Scheier, J.). The reason the 43038A Plan only shows the northern boundary to the 1946 high water mark is simple. The Eisingers had not submitted a proper survey of that portion of their land. The plan they submitted (the November 1993 Rogers Plan) showed the accreted upland extending straight outward from the pre-accretion boundary lines. This was an incorrect depiction. The correct location of the accreted boundaries on the Cove requires application of the pie method as shown on Exhibit 3, resulting in an angle. See n. 8, supra. The Eisingers did not have such a survey done at that time, apparently for reasons of cost. See letter to the court from petitioners counsel Sarah Turano-Flores at 2 (Aug. 9, 1999). Thus, the 43038A plan goes only as far as the 1946 high water mark, where the pie method angles would start. See Ex. 3. The Decree and judgment control. Ms. Eisingers pre-S-case registration grants her registered title to the current mean high water mark, which I affirm. A new plan shall now issue to show that line.

The remaining lot at issue is Lot 58, conveyed by Ms. Snow in 1956 to the Paulicks predecessor and described as Lot #58 on [the subdivision plan (Exhibit 1)], and its side and waterside boundaries as running Northeasterly by Lot #57 226 feet more or less to Chipman Cove; thence turning and running Southeasterly by Chipman Cove to Lot #59; thence turning and running Southwesterly by Lot #59 227 feet more or less to the point of beginning. [Note 26] I conclude (and so find) that Ms. Snow intended the sea-ward boundary to be the mean high-water mark, and for this to be a moveable boundary as set forth above, for the following reasons. First, again, each of these deeds references the 1922 subdivision plan (Ex. 1) which shows the sea-ward boundary of each lot as the high water line. Second, Ms. Snows 1957 conveyance of the shore and flats to the Wellfleet Land Company shows she believed she retained ownership of the flats. Third, neither in this deed, nor in any other of the individual lot deeds she granted, did she reference the sea-ward boundary as the channel of a cove or by said channel, which she knew from her deed from Hilda Baker described the boundary of the flats. Fourth, even though some of the deeds she granted describe the sea-ward boundary of the lots as to or by the Cove and others to or by the high water mark or line, I conclude (and so find) that she intended consistency and thus that each of these meant the mean high water mark. To conclude otherwise is to create a pattern along the Cove with no rhyme or reason. Lots 65 and 67, for example, describe the sea-ward boundary as to or by the Cove, [Note 27] yet Lot 66, between them, describes its sea-ward boundary as to or by the high water line. [Note 28] To assume she intended a gap, with a community beach in the center (Lot 66) completely inaccessible to the community because it is bordered on both sides by completely private beaches (Lots 65 and 67), makes no sense. Fifth, and perhaps most tellingly, Ms. Snows deed most immediately following her conveyance of the shore and flats to the Wellfleet Land Company (her deed of Lot 62) described Lot 62s sea-ward boundary as to and by the Cove [Note 29] a boundary that, because of the prior conveyance of the flats to the Wellfleet Land Company, could only have gone to the mean high water line. That she was more precise in her subsequent deeds (describing their sea-ward boundary as to or by the high water mark or the land of the Wellfleet Land Company) does not mean she previously had a different intent.

I also find, as with Lot 66, that she intended a moveable boundary. The subdivision plan, whose lot depictions she so carefully followed, show the sea-ward boundary of the lots at the high water line, i.e. with no flats, and a line that moves over time. The plan shows the sea-ward boundaries as including all of the upland (i.e., all the way to the high water line). And the geography I observed at the view shows the logic of accreting all new upland to the previous upland to preserve the integrity and privacy of the small shorefront house lots, and thus the likely intent to do so.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the petitioners have registrable title to the accreted upland associated with their lots, out to the current mean high water mark, in accordance with the lines shown on Exhibit 3. I further find and rule that they do not have title to any of the current flats. Finally, I find and rule that the areas of pre-accretion and post-accretion flats within the land registered in these cases are subject to the publics rights as set forth in the Paulick and Eisinger Stipulations.

Registration shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

By the court (Long, J.)

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Exhibit 3

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] The Town of Wellfleet was duly served but did not actively participate in either of these cases.

[Note 2] Dr. Eisinger died on December 20, 2008. His surviving spouse, Miriam Eisinger, is now the sole petitioner in Case No. 02 SBQ 43038 (KCL).

[Note 3] The two cases were consolidated for discovery, pre-trial and trial purposes, but remain separate proceedings. See Order on Petitioners Motion to Consolidate (Dec. 12, 2005).

[Note 4] According to the testimony at trial, the tide rises and falls approximately ten feet in Chipmans Cove. Transcript at 78 (testimony of surveyor Chester Lay) (Sept. 9, 2010).

[Note 5] The shaded areas on Exhibit 3 indicate the additional accreted upland for the Paulick and Eisinger properties.

[Note 6] They thus make no claim to any newly created flats beyond the pre-dredging line. There was no evidence regarding the location of the new low water mark. The petitioners believe that it is probably in the same location as the pre-dredging line and thus that they were not giving up much square footage by not claiming it. Transcript at 143 (statement of petitioners counsel) (Sept. 9, 2010).

[Note 7] The result is different when the dumping is done as a necessary aid to navigation. In that case, the accretion belongs to the government. Lorusso, 408 Mass. at 780.

[Note 8] Each of the lot owners along the relevant area of the Cove was served with a copy of Exhibit 3 and invited to intervene if they had any objection to the method of division. None sought such intervention, nor raised any objection to the methodology. I find that the division shown on Exhibit 3 is the most appropriate division, and shows the appropriate boundary lines measured to the present mean high water mark, for the lots at issue in these cases. See Lorusso, supra; C.M. Brown et al., Browns Boundary Control and Legal Principles (4th Ed.,1995) at 196, describing the so-called pie method (For curving shorelines, the general rule is to proportion the area based on length of the shoreline and length of an outer line).

[Note 9] She too has entered into a stipulation disclaiming all interest in the flats beyond the pre-dredging line. Stipulation between Petitioners and the Commonwealth at 2 (Sept. 9, 2010) (Eisinger Stipulation).

[Note 10] Although the registration plan (43038A) shows Ms. Eisingers registered land only to the pre-accretion (1946) mean high water mark (the reasons for this survey related -- are discussed below), it is clear from the Decree that her registered title extends to the post-accretion mean high water mark. The Decree describes her northerly boundary as by Chipmans Cove, determined by the court to be located as shown on a plan drawn by William N. Rogers, Surveyor, dated November, 1993, as modified and approved by the court. That plan shows the northerly boundary as by the November 10, 1993 (i.e. post-accretion) mean high water mark. Decree Plan (Jun. 8, 1999, Scheier, J.). The Eisingers had earlier voluntarily withdrawn their claim to register the post-accretion flats. See letter to the court from petitioners counsel Sarah Turano-Flores at 2 (Aug. 9, 1999).

[Note 11] The Trust obtained such title as it has by deed from John and Nathaniel Snow, asserted to be the successors to the title (if any) of Wellfleet Land Co. in the flats of Chipmans Cove. See discussion below of Wellfleet Land Co.s claims. Snow to Trustees of Wellfleet Conservation Trust (Dec. 29, 2001). As discussed again below, I need not and do not decide the validity of the Trusts title (these are registration petitions, and thus adjudicate only the petitioners titles). It is sufficiently colorable, however, to give the Trust standing to press its objections in these cases.

[Note 12] Both the Paulicks and Ms. Eisinger agreed that the land between the pre-dredging and post-dredging mean high water marks was filled tidelands, subject to the Commonwealths jurisdiction and the licensing requirements of Massachusetts General Laws. Chapter 91 and 310 CMR 9:00, and that the area between the current mean high water mark and the current mean low water mark is subject to the rights and interests of the public. Paulick Stipulation at 1-2; Eisinger Stipulation at 1-2.

[Note 13] Luther Crowell to M. Burton Baker (Dec. 10, 1921).

[Note 14] M. Burton Baker to Kenneth Burton Baker (Aug. 12, 1931). Each subsequent conveyance of Lot 57 contained the same property description.

[Note 15] It is unclear why Mr. Baker referred to Indian Neck Cove as opposed to Chipman Cove but it is clear what he meant. The subdivision plan (Exhibit 1) contains labels for all three bodies of water it depicts (CAPE COD BAY to the west, SEWELLS GUTTER to the south, and CHIPMAN COVE to the north). The name Indian Neck Cove is not used on that plan, but since each Cove-side lot is bounded by only one cove (Chipman Cove) and since the property is specifically referenced as lot 57 as shown on the plan, Mr. Baker clearly was referring to Chipman Cove when he described it as Indian Neck Cove.

[Note 16] M. Burton Baker to Kenneth B. Baker (Aug. 12, 1931).

[Note 17] Those bounds are not shown on the plan.

[Note 18] I say this for two reasons. First, the two side measurements are each 172.50 feet. Given the curve of the Cove, it is impossible to believe that the bottom of the bank was precisely the same distance on both sides. The second is based on my observations at the view. The banks now, and likely then, started relatively flat and then sloped seaward, at some points quite steeply. The bounds referenced in the deed (e.g. one hundred seventy-two and 50/100 (172.50) feet to a bound) would thus likely not have been at the bottom of the bank (where the water met the land) but at some more permanent point higher up. See Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 830-831.

[Note 19] Baker to Baker, et ux. (Apr. 12, 1933).

[Note 20] Kenneth and Hilda Baker to Richard Baker (May 24, 1937).

[Note 21] Kenneth and Hilda Baker to Higgins (May 22, 1943).

[Note 22] Lots 75, 76, and 77 had their sea-ward boundaries described as to or by Indian Neck Cove so called rather than by bottom of bank (perhaps the bank was not as pronounced in that particular location at that time?), but any ambiguity as to what boundary was meant was resolved by her very specific reference to all my right, title and interest to Lots 75, 76 and 77 as shown on said Subdivision Plan [Ex. 1], containing respectively 19,000 square feet more or less, 9,000 square feet and 8,551 square feet, i.e. to the high water line. Hilda Baker to Spence (Apr. 24, 1946). Hildas deed of Lot 74 a few months later again described the lot by reference to the subdivision plan (Ex. 1), and gave its sea-ward boundary as the high water mark. Hilda Baker to Enos (Aug. 31, 1946). Her deed of Lots 63 and 64 a few months after that again described the lots by reference to the subdivision plan (Ex. 1), and the sea-ward boundary as to and by Indian Neck Cove. Hilda Baker to Mulhern (Nov. 15, 1946). Surely consistency across all these deeds was intended, and I find that the use of to and by the Cove in the Spence and Mulhern deeds, clarified by the specific reference to the subdivision plan, was intended to give the boundary as the high water line since that is the dividing mark shown between the lots and the Cove on the plan (the flats are not separately shown). Had Ms. Baker intended to convey the flats, she would have described the sea-ward boundary as to or by the channel of a cove or by said channel as she did in her 1949 deed to Dorothy Snow, discussed below.

[Note 23] Hilda Baker to Snow (Feb. 8. 1949).

[Note 24] Snow to Toko, et al. (Jul. 19, 1955). Each subsequent conveyance used the same description.

[Note 25] Snow to Wellfleet Land Co. (May 17, 1957).

[Note 26] Snow to Godwin, et ux. (Aug. 17, 1956). Each subsequent conveyance used the identical description.

[Note 27] Snow to Nichols (Jan. 17, 1955); Snow to Conners (Sept. 8, 1955).

[Note 28] Snow to Toko (Jul. 19, 1955).

[Note 29] Snow to Upton (Jun. 30, 1960).

WULF PAULICK and RENATE PAULICK v. WELLFLEET CONSERVATION TRUST, TOWN OF WELLFLEET [Note 1] and the COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS

WULF PAULICK and RENATE PAULICK v. WELLFLEET CONSERVATION TRUST, TOWN OF WELLFLEET [Note 1] and the COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS