Introduction

Plaintiffs Donald and Tina Tucker (the Tuckers), together with certain other nearby residents, brought this G.L. c. 40A, § 17 action, seeking reversal of the Salem Zoning Board of Appeals (the Board) decision to grant variances and a special permit to defendant Peter Copelas, the owner of the property at 3 Webster Street, and to developer-defendant Lewis Legon, which would enable them to convert the existing commercial building to a six unit residential condominium. [Note 1] Mr. Copelas building was once a trolley barn, and has most recently been used as a workshop and warehouse space. The Board granted variances from minimum lot area per dwelling and off-street parking requirements, and also issued a special permit to change one nonconforming use (warehouse) to another nonconforming use (six residential units within a two-family residential (R2) zoning district). The Board found that all requirements for the issuance of these variances were met. The Board also found that the residential use proposed is more in keeping with the residential character of the R-2 zone than a commercial use, and that this zoning relief could be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of the zoning ordinance . . . . Salem Zoning Board of Appeals Decision at p. 2 (June 29, 2009)

The plaintiffs argue otherwise, contending that the Board lacked sufficient factual and legal grounds for granting the variances and the special permit and exceeded its authority in doing so. The defendants defend the Boards decision and, additionally, challenge the plaintiffs standing to bring this action.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find that the plaintiffs failed to carry their burden by putting forth credible evidence establishing their standing to bring this action. The plaintiffs appeal is therefore DISMISSED in its entirety, WITH PREJUDICE. Moreover, even if the plaintiffs had proven their standing and the merits were reached, the evidence demonstrated that the Board had both the authority and sufficient legal and factual grounds to issue the variances and special permit.

Facts

The Copelas Property

Mr. Copelas purchased 3 Webster Street in 1986. The property consists of a two-story brick building that occupies nearly the entire one-hundred-by-fifty-foot rectangular lot. The building is located in a residential two family (R2) zoning district. It has no front or rear set-back, and only about a one-foot set-back on each side of the lot. An emblem inscribed A.D. 1887 is located above the second-floor windows on the front exterior of the building. The buildings two floors contain approximately 9,600 square feet of unfinished floor space. At present, the building has no water, oil, gas, or heat. It has electricity for lighting.

In its early years, the building was a trolley barn that housed street cars, but between the mid-twentieth century and Mr. Copelas purchase in 1986, the building was used as warehouse storage space for a hardware store. After Mr. Copelas purchased the building, he rented space to woodworking and welding shops, which operated in limited sections of the building for the small-scale manufacturing of cabinets and similar products. All woodworking activity, including Mr. Copelas own Naumkeag Woodworking business, ceased approximately three years ago. The building is currently used for linen and equipment storage in connection with Mr. Copelas laundry service business as well as for miscellaneous storage.

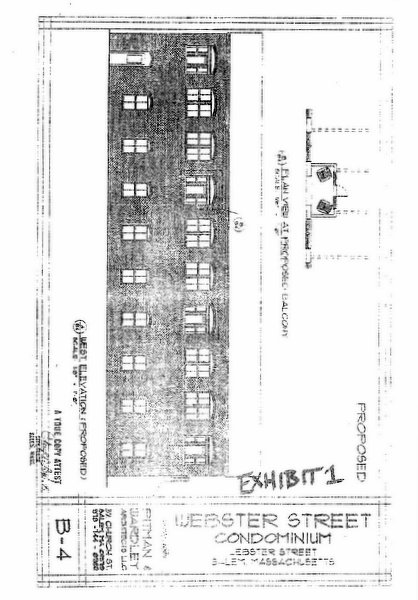

A few years ago, defendant Lewis Legon, a Salem-area real estate developer, approached Mr. Copelas about the possibility of buying the building and redeveloping it for residential use. Mr. Legon entered into a contract to purchase the building from Mr. Copelas for approximately $320,000. The original plans drawn up by Mr. Legons architect depicted an eight unit condominium. However, in response to comments by neighbors, the proposal was reduced to six units, three on each floor, with three off-street parking spaces located inside the building on the first floor. The units would have mid-level finishes, two bedrooms, and would be marketed to single or professional couples and older couples seeking to downsize. The exterior of the building would be substantially identical to what it is today. The only significant change to the buildings exterior would be the construction of three 12 x 6 cut in [Note 2] balconies on the second floor, one for each of the three units on that floor, which would provide views of Salem Harbor. (See Trial Exhibit 7 attached to this Decision as Exhibit 1). [Note 3] The cut in design would, therefore, not extend the exterior of the building beyond its current footprint. The contract between Mr. Legon and Mr. Copelas was contingent on obtaining the necessary approvals for a six unit building from the Board, and when the Boards approval was appealed, the contract terminated. At the time of trial, Mr. Legon had no legal interest in the property.

Five - Seven Webster Street and the Webster Street Neighborhood

In 1983, Mr. Copelas also owned the property next-door to his building at 5-7 Webster Street, and began renting that property to Mr. Tucker who used it to operate a machine shop. The property had been used as a machine shop prior to the Tuckers arrival, and as a single family residence before that. Mr. Tucker subsequently purchased this property from Mr. Copelas in the mid-1980s. Around 1996, Mr. Tuckers business outgrew 5-7 Webster Street so he renovated the building into a two-story, single family residence, with a one-story attached garage that supports a deck on the roof. During the fall of 2000, the Tuckers moved into the building and have resided there since. The Tuckers property also contains a two car driveway between their garage and the Copelas building. They have three vehicles, which they prefer to park on Webster Street in front of their house.

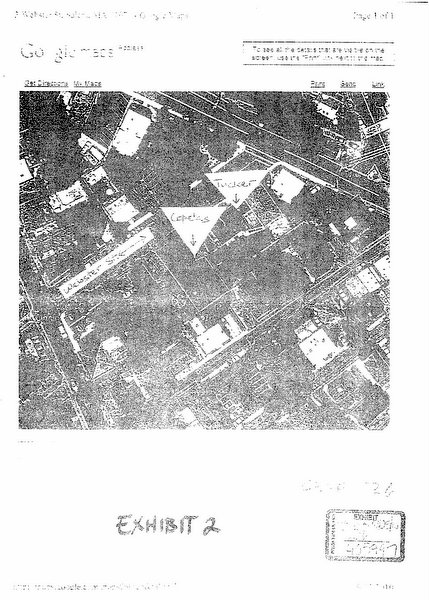

The Tucker home and the Copelas building are located in a dense, residential neighborhood approximately four blocks north of Salem Common. (See Trial Chalk 26, attached as Exhibit 2, depicting the immediate area around Webster Street and Trial Chalk 27, attached as Exhibit 3, depicting the overall neighborhood). The neighborhood consists of single-family, two-family, and multi-family buildings with some commercial spaces that include a prepared food business and a music store. On-street public parking is allowed on both sides of Webster Street except during the month of October, when Webster Street is restricted to resident-only parking for the height of the Salem tourist season during Halloween. There is space for approximately 22 cars to park on Webster Street, and there are other public parking spaces on the adjoining streets. The photographs introduced at trial, taken at various times, show many of these spaces vacant and thus available for immediate use.

Aside from the Copelas and Tucker properties, there are two, single family homes located at 1 and 4 Webster Street. The residents of 1 Webster Street (the Coxes), located on the other side of the Copelas building, regularly park their two vehicles on either the street or in their driveway. They are not plaintiffs and have raised no objection to the proposed condominium development. The residents of 4 Webster Street (the Erwins), located across the street from the Copelas building and the Tuckers, have three vehicles and tend to park two on the street, and one in their driveway. Three other properties have lot lines along Webster Street; these include 15 Pleasant Street (the Guidos), 117 Webb Street (the Sousas) and a two family condominium that fronts Pleasant Street and abuts the Cox residence. The Guidos have three cars that they park in their driveway. The Sousas have four cars, and their property consists of a three family building and a large, paved parking area with spaces for six cars and a driveway area that can accommodate additional cars. The two-family condominium on Pleasant Street has four cars that its residents park in the driveway. Except for the Erwins at 4 Webster Street and Mr. Copelas building, each lot on Webster Street has sufficient off-street space for the respective owners to park all of their vehicles. As discussed in more detail below, because of the density of the neighborhood, several residences abut the Tuckers backyard and some have direct views from windows and porches into the Tuckers windows, deck and yard. The other plaintiffs properties also each lack privacy for the same reasons.

The Grant of Variances and Special Permit

On May 17, 2009, Mr. Legon and Mr. Copelas petitioned the Board for variances from the minimum lot area per dwelling and parking space requirements applicable to the Copelas building under Article VI, § 6-4, Table I of the Salem Zoning Ordinance (Zoning Ordinance) and a special permit to change from one nonconforming use to another pursuant to Article VIII, § 8-6 of the Zoning Ordinance. Specifically, they requested a variance from the residential density requirement of a minimum of 7,500 square feet of lot area per dwelling unit to a proposed 833 square feet per dwelling unit. Mr. Legon and Mr. Copelas also sought a second variance from the required 1 ½ off-street parking spaces per dwelling unit (a total of nine spaces for all six units) to the proposed three off-street parking spaces located inside the buildings first floor. The special permit they applied for would allow a change from one nonconforming use, warehouse/woodworking space, to another nonconforming use, a six unit residential building within the two-family R-2 residential zoning district.

A public hearing was held on June 17, 2009, and the Board issued its decision shortly afterward on June 29, 2009. The Board found there were special circumstances, due in part to the buildings age and size, which did not affect other parcels in the district, and that made it difficult to meet the lot area and off-street parking requirements. The Board found that the proposed residential use would be more in keeping with the residential character of the neighborhood and the desired relief could be granted without substantial detriment to the public good. The Board also found that literal enforcement of the Zoning Ordinance would cause substantial hardship to Mr. Copelas. Based on these findings, the Board granted the variances and also approved the special permit. On July 17, 2009, the plaintiffs brought this G.L. c. 40A, §17 appeal, seeking to annul the Boards decision.

Further facts are included in the analysis set forth below.

Analysis

Standing

Only a person aggrieved by a zoning board decision has standing to appeal. G.L. c. 40A, § 17. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Watros v. Greater Lynn Mental Health & Retardation Assn, Inc., 421 Mass. 106 , 107 (1995); Green v. Board of Appeals of Provincetown, 404 Mass. 571 , 574, 536 N.E.2d 584 (1989). ). A plaintiff qualifies as a person aggrieved upon a showing that his or her legal rights will be infringed by the boards action. To show an infringement of legal rights, the plaintiff must show that the injury flowing from the boards action is special and different from the injury the action will cause the community at large. Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005) (citations omitted). Furthermore, the injury must be to a specific interest that the applicable zoning statute, ordinance, or bylaw at issue is intended to protect. Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 30 (2006) (citing Circle Lounge & Grille, Inc. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 324 Mass. 427 , 431 (1949)).

Under G. L. c. 40A, an abutter is presumptively a person aggrieved. G. L. c. 40A, § 11; Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. However, a defendant may challenge the plaintiffs standing by offer[ing] evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33 (quoting Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003)). [Note 4] Once the presumption has been rebutted, the issue of standing is decided on the basis of the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiff from the presumption. Id. (quoting Barvenik v. Aldermen of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132 (1992)); Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

Whether a plaintiff has proved standing is a question of fact for the court. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 440. However, this does not require that the factfinder ultimately find a plaintiffs allegations meritorious. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. Standing is the gateway through which one must pass en route to an inquiry on the merits. When the factual inquiry focuses on standing, therefore, a plaintiff is not required to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that his or her claims of particularized or special injury are true. Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 440-41. The plaintiff is only required to put forth credible evidence to substantiate his allegations. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721.

The court in Butler addressed what constitutes credible evidence in zoning cases.

Although decided zoning cases have not discussed the ingredients of credible evidence, cases discussing the same concept in other contexts have observed that credible evidence has both a quantitative and a qualitative component. We think the same approach is appropriate here. Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the boards action. Conjecture, personal opinion, and hypothesis are therefore insufficient. When the judge determines that the evidence is both quantitatively and qualitatively sufficient, however, the plaintiff has established standing and the inquiry stops.

Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441-42 (citations omitted).

The parties stipulated that all named plaintiffs are parties in interest and are presumed to have standing to pursue this appeal. [Note 5] The Tuckers were the only plaintiffs to appear at trial. They claim they have been aggrieved by the Boards decision based on, essentially, two theories. First, they contend the development of the Copelas building will harm them and every other named plaintiff by resulting in increased traffic congestion and a loss of on-street parking spaces. Second, they allege specific harm to their privacy due to increased noise and light pollution, and sight lines from the windows of the Copelas building that will give potential residents a direct view into their backyard. The plaintiffs contend these are specific interests that the Salem Zoning Ordinance is intended to protect, and are sufficient to confer standing. See Salem Zoning Ordinance Art. I at p. 3 (stated purposes include to lessen congestion in the streets

to prevent overcrowding of land; to avoid undue concentration of population

[and] to encourage the most appropriate use of land). For the purposes of this Decision, I assume these interests are protected by the Zoning Ordinance.

After hearing all the evidence presented at trial, I find that Mr. Copelas successfully rebutted the plaintiffs presumption of standing. There was no credible evidence, expert or otherwise, showing that the Copelas condominium development would increase traffic congestion. With respect to parking, Mr. Copelas produced testimony and exhibits that show the properties on Webster Street, in almost every case, contain off-street parking sufficient to meet the needs of each property owner. Although Mr. Tucker likes to park on the street, he has a one car garage and a two car driveway that can accommodate his three cars (although he chooses to use part of his driveway to store a motorbike). In addition to the off-street parking on Webster Street, the street itself is wide, and parking is permitted on both sides, resulting in additional on-street parking for approximately 22 vehicles. As previously noted, photos of Webster Street taken at various times show plenty of space for on-street parking and vacant spaces available for immediate use. At least one of the reasons why this is so, despite the density of the neighborhood, is readily apparent. The need for a car and the overall use of cars is substantially reduced by the availability of public transportation (the Salem commuter rail stop is located nearby) and of shops within walking distance. The residents of the Copelas condominiums who do have a car and who do not park in one of the spaces inside the building could easily find space either on Webster Street or on one of the neighboring streets without much difficulty, and there was no credible evidence that any of the plaintiffs parking opportunities will truly be affected by these additional cars. As noted above, nearly all presently park on their properties and the 22 on-street spaces are more than sufficient to accommodate any additional parking they need plus any cars associated with the Copelas condominiums.

Mr. Copelas also presented evidence demonstrating that the Webster Street area is a dense, urban neighborhood. As it stands now, the plaintiffs have no real privacy. For example, the trial exhibits show that the Tuckers deck atop their garage is plainly visible to any pedestrian walking down Webster or Spring Streets. The Tuckers backyard can also be viewed from a second story deck at 9 Spring Street and from the second and third story porches of 11 Spring Street, directly behind the Tuckers backyard. [Note 6]

The evidence showed the Tuckers are not insulated from noise generated by their abutting neighbors. For instance, the three family building at 11 Spring Street, directly abutting the Tuckers yard, has a paved backyard area with a basketball hoop. Another house, at the corner of Webb and Webster Streets has a paved driveway and parking area abutting the Tuckers fence. The two family house at 97-99 Webb Street, also abutting the Tuckers yard, contains a childrens outdoor play set, patio furniture and a grill, all in close proximity to the Tuckers fence. I find that noise from any of these abutting yards is capable of being heard by the Tuckers when they use their own backyard. Moreover, any noise generated by the Copelas condominiums will be minimal and muted. The Copelas building has no exterior yard, and the only exterior spaces contemplated are those on the small, cut in balconies. See Exhibit 1. With room for two seats at best, they are hardly party centers.

Mr. Copelas further showed that the development of his building will not lead to a detrimental increase in artificial light that will harm the Tuckers. Again, due to the urban character of this neighborhood, residents cannot completely eliminate the artificial light around them. For example, the trial exhibits show there are two street lights in close proximity to the windows of the Tuckers house. Based on the evidence presented, it is unlikely that light emitted from the Copelas building will negatively impact the Tuckers. First, there are no plans to add more windows to the building. The number of windows that face the Tuckers property will remain the same if the building were developed into six units or one unit, and these windows are approximately 60 feet away from the second story windows of the Tuckers house. Second, even if the building were torn down and replaced with a single family house, Mr. Tucker acknowledged at trial there would still likely be windows capable of emitting light in the direction of his property. Finally, the defendants have no plans to place any exterior lights on the side of the building facing the Tuckers. The plans only show one exterior light above the entrance to the building on Webster Street where one presently exits.

The evidence presented by Mr. Copelas is thus sufficient to [warrant] a finding contrary to the presumed fact[s] that the development of the building will result in an injury to the plaintiffs through an increase in traffic congestion, a reduction of on-street parking spaces, and a decrease in privacy. See Standerwick, 447 Mass. At 33 (quoting Marinelli, 440 Mass. at 258).

With Mr. Copelas having successfully challenged the plaintiffs presumptive standing, the burden remains on them to prove their standing through credible evidence, leaving the question of standing to be decided on all the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiffs from the presumption. Marotta v. Bd. of Appeals of Revere, 336 Mass. 199 , 204 (1957). Since no other named plaintiffs appeared at trial and attempted to prove their standing as aggrieved persons, and since the evidence discussed above shows there will be no such aggrievement, I find that their G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal necessarily fails and they are dismissed from this action with prejudice.

The Tuckers attempted to prove their standing by offering testimony from Mr. Tucker about potential parking and privacy impacts, but this evidence failed to carry their burden. The Tuckers offered no expert testimony on any of the harms they allege. Compare with Hoffman v. Bd. of Zoning Appeal of Cambridge, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 804 , 808 (2009) (standing found where plaintiff presented testimony of licensed traffic engineer who had performed traffic analysis on parking impacts resulting from new development). Instead they relied solely on Mr. Tuckers assertions that residents from the surrounding streets routinely park on Webster Street, thereby making parking on the street difficult. [Note 7] As previously noted, there was no credible evidence that a minor increase in the number of cars in the neighborhood will substantially lessen the availability of on-street parking. Given the close proximity of the residences in the neighborhood, which already limits the Tuckers privacy, there was no evidence presented to show why the development of the Copelas building would have a further detrimental impact on the Tuckers privacy.

In essence, the Tuckers case amounted to a series of hypothetical concerns based on the fact that people will be living in a building that is currently only used periodically for warehouse purposes. Simply asserting that any use of the Copelas building that is over and above its present use would result in a particularized injury to the Tuckers is not the type of credible evidence that is needed to sustain the plaintiffs burden. See Butler, 63 Mass. App. Ct. at 441-42 (citations omitted).

Since the Tuckers failed to carry their burden to prove standing, the court need not reach the merits of the Boards decision. However, even if the Tuckers had been able to establish standing and assert their case on the merits, the result would be no different.

Review of the Boards Decision Pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, § 17

In a G. L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal, the court is required to hear the case de novo, make factual findings, and determine the legal validity of the Boards decision based upon those findings. Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 486 (1999) (citing Bicknell Realty Co. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 330 Mass. 676 , 679 (1953); Josephs v. Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 295 (1972)). The court gives no evidentiary weight to the boards findings. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486 (citing Josephs v. Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 295 (1972)). The courts function on appeal, based on the facts it has found de novo, is to ascertain whether the reasons given by the [Board] had a substantial basis in fact, or were, on the contrary, mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purposes of the zoning law. Vazza Properties, Inc. v. City Council of Woburn, 1 Mass. App. Ct. 308 , 312 (1973). The Board must have acted fairly and reasonably on the evidence presented to it, and have set forth clearly the reason or reasons for its decisions, in order to be upheld. Id.

Even though the case is heard de novo, such judicial review is nevertheless circumscribed: the decision of the board cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486 (citations omitted). In determining whether the decision was based on a legally untenable ground, the courts must determine whether it was decided

on a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws. Here, the approach is deferential only to the extent that the court gives some measure of deference to the local boards interpretation of its own zoning by-law. In the main, though, the court determines the content and meaning of statutes and by-laws and then decides whether the board has chosen from those sources the proper criteria and standards to use in deciding to grant or to deny the variance or special permit application.

Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003) (internal citations omitted). In determining whether the decision was unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary, the question for the court is whether, on the facts the judge has found, any rational board could come to the same conclusion. Id. at 74. This step is highly deferential. Id. While it is the boards evaluation of the seriousness of the problem, not the judges, which is controlling, Barlow v. Planning Bd. of Wayland, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 314 , 321 (2005) (internal quotations and citations omitted); Titcomb v. Bd. of Appeals of Sandwich, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 725 , 732 (2005) (same), and a highly deferential bow [is given] to local control over community planning, Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73, deference is not abdication; the boards judgment must have a sound factual basis. Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 74-75 (to be upheld, the boards decision must be supported by a rational view of the facts). If the Boards decision is found to be arbitrary and capricious, the court should annul the decision. See, e.g., Colangelo v. Bd. of Appeals of Lexington, 407 Mass. 242 , 246 (1990); Mahoney v. Bd. of Appeals of Winchester, 344 Mass. 598 , 601-02 (1962). If it is not, it must be upheld. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486. Here, the Boards decision was not arbitrary and capricious and it must be upheld.

The Variances Issued to Mr. Copelas Were Justified

Variances are governed by G.L. c. 40A, § 10 which states, in pertinent part:

The permit granting authority shall have the power

to grant upon appeal or upon petition with respect to particular land or structures a variance from the terms of the applicable zoning ordinance or by-law where such permit granting authority specifically finds that owing to circumstances relating to the soil conditions, shape, or topography of such land or structures and especially affecting such land or structures but not affecting generally the zoning district in which it is located, a literal enforcement of the provisions of the ordinance or by-law would involve substantial hardship, financial or otherwise, to the petitioner or appellant, and that desirable relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of such ordinance or by-law.

These requirements are also reflected in the Salem Zoning Ordinance. See Art. IX,

§ 9-3(d)(3) and § 9-5(b)(1).

The Supreme Judicial Court has repeatedly held that no variance can be granted unless all of the requirements of this statute are met. Warren v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Amherst, 383 Mass. 1 , 9-10 (1981). [A] failure to establish any one of them is fatal. Guiragossian v. Bd. of Appeals of Watertown, 21 Mass. App. Ct. 111 , 115 (1985) (citing Blackman v. Bd. of Appeals of Barnstable, 334 Mass. 446 , 450 (1956)). [T]he burden rests upon the person seeking a variance

to produce evidence at the hearing in the [Land Court] that the statutory prerequisites have been met and that the variance is justified. Dion v. Bd. of Appeals of Waltham, 344 Mass. 547 , 555-556 (1962).

In its decision, the Board made the following findings:

1. Special conditions and circumstances exist affecting the parcel and building, which do not generally affect other land or buildings in the same district. The building, constructed in the 1880s, was built to the lot lines, taking up the entire parcel. This makes it difficult to accommodate all of the required parking on site, and difficult or impossible to meet the zoning requirements for lot area per dwelling unit in the R-2 zone for any residential development, without tearing down the structure.

2. Desirable relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of the zoning ordinance, as the changes proposed would result in significant improvements to the property at 3 Webster Street. Additionally, the residential use proposed is more in keeping with the residential character of the R-2 zone than a commercial use.

3. Literal enforcement of the provisions of this ordinance would involve substantial hardship, financial or otherwise, to the appellant.

4. The applicant may vary the terms of the Residential Two-Family District to construct the proposed development, which is consistent with the intent and purpose of the City of Salem Zoning Ordinance.

5. In permitting such change, the Board of Appeals requires certain appropriate conditions and safeguards as noted below. [Note 8]

Decision at p. 2 (June 29, 2009). The Tuckers contend that the Boards decision fails as a matter of law because it lacks specific findings as to why a literal enforcement of the Zoning Ordinance would involve substantial hardship and instead relies on a mere repetition of the statutory words. Warren, 383 Mass. at 10 (internal quotations and citations omitted). Standing on its own, the Boards third finding is simply a repetition of the language found in the statute, but when read in conjunction with the other findings contained in the decision, the Boards conclusion regarding hardship is adequately supported by specific facts. Specifically, the Board found at paragraph 1 that the buildings configuration (built to the lot lines and taking up the entire parcel) made it difficult to meet the off-street parking requirement. Moreover, the Board found that it would be impossible to meet the zoning requirements for lot area per dwelling unit in the R-2 zone for any residential development, without tearing down the structure. Decision at p. 2 (June 29, 2009). Based on my de novo review of the evidence, I concur with each of these findings. They show the special circumstances of the building, and also show that a literal application of the Zoning Ordinance could not be done without substantial financial cost and other hardship to Mr. Copelas.

Like the Board, I find that there are specific circumstances that relate to this building that are not shared by other buildings in the zoning district. The Copelas building is a two story brick structure, constructed in the 1880s and built to almost the full extent of the lot lines. Its features are unique in the neighborhood, which is composed of single and multi-family residences, mostly constructed out of wood and each containing some driveway or yard space. The building has an historic aspect to it, having once been the Salem Trolley Building, and it retains a large, garage door on Webster Street where trolleys once passed through.

I also find that a literal enforcement of the Zoning Ordinance would involve substantial financial and other hardship. [Note 9] Extensive work would be needed to make the building suitable for residences. This includes a substantial renovation of the buildings infrastructure, which would require installing a heating system, new plumbing and drainage, insulating the building, installing new windows and repairing the masonry around the windows, conducting structural engineering to ensure the safety and integrity of the building, installing a new electrical system, and air conditioning units. This work would be needed whether the building was developed into a one or two family residence, as the Tuckers prefer, or a six unit condominium, and the cost would approach or exceed $1,000,000. This substantial, upfront investment also renders a one or two unit residence economically infeasible. Based on his familiarity with the Salem real estate market, Mr. Legon credibly testified that there simply was no market in that particular neighborhood of Salem for a 10,000 square foot, one family residence priced at approximately $1,000,000 or two 5,000 square foot units each priced at or above $500,000.

This hardship also exists if the building were to be marketed as commercial warehouse space instead of a residence. Mr. Copelas provided testimony from David Hark who has 30 years of experience selling and leasing residential and commercial real estate around Salem. Given the buildings present condition, it could not be rented as a warehouse without making the same basic infrastructure upgrades that would be required if the building were to be converted to residences. From a marketing standpoint, the buildings location in a residential neighborhood also makes it difficult to market to a potential warehouse lessee or buyer because there would likely be concerns about potential conflicts with the surrounding neighbors. Additionally, Mr. Hark testified there was an over-supply of warehouse space, not just because of the recession, but also because of the changing nature of business. Many products are not inventoried locally, and instead are shipped overnight from large warehouses in other parts of the country, which depresses demand for local warehouse space. At the time of trial, there was approximately 250,000 square feet of vacant warehouse space in Salem, and all of that space had advantages to potential lessees or buyers such as newer facilities and modern utility systems, all of which would make it difficult for the Copelas building to compete in the commercial real estate market. It was Mr. Harks opinion, based on his marketing perspective, that it would not be cost effective for a potential lessee or buyer to rent or buy the building unless they had plans to use it much more actively than Mr. Copelas presently does. This kind of active use would create a far greater impact on the surrounding neighborhood in the form of increased noise from frequent deliveries and employees who would need to park on Webster Street.

I also find that the facts presented at trial support the Boards finding that desirable zoning relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of the zoning ordinance. See G.L. c. 40A § 10; Salem Zoning Ordinance, Art. IX § 9-3 at p. 54. For the reasons already discussed in the analysis of the Tuckers standing (see above), the proposed development will not result in a substantial detrimental impact on traffic, parking or privacy in the Webster Street area. In fact, as the Board noted in its decision, a majority of letters received from neighbors believed the project would benefit the surrounding neighborhood by improving the overall appearance of a building that is presently in disrepair. See Decision at p. 1 (June 29, 2009). Moreover, Mr. Harks testimony about the potential effects of an actively used warehouse supports the Boards finding that a residential, rather than a commercial use, is more in keeping with the character of the R-2 zoning district.

The Board Complied with the Zoning Ordinance in Issuing the Special Permit

The Tuckers argue that the Boards decision to grant a special permit to Mr. Copelas to change one nonconforming use to another nonconforming use fails as a matter of law for two reasons. First, they contend that Mr. Copelas has ceased using the building for warehouse purposes and under the Salem Zoning Ordinance, [i]f any nonconforming use of land is discontinued for any reason for a period of twelve 12 consecutive months, any subsequent use of land shall conform to the regulations specified by this ordinance

. Salem Zoning Ordinance, Art. VIII, § 8-5 at p. 51. Second, they argue the Board exceeded its authority to grant a special permit because structural alterations will be made to the Copelas building and the Zoning Ordinance prescribes, [i]f no structural alterations are made, any nonconforming use of a structure or structure and premises may be changed to another nonconforming use, provided that the board of appeals, either by general rule or by making findings in the specific case, shall find that the proposed use is equally appropriate or more appropriate to the district than the existing nonconforming use. Salem Zoning Ordinance, Art. VIII, § 8-5(4) at p. 52. I disagree with these contentions.

The provision of the Zoning Ordinance cited by the Tuckers on the discontinuation of a nonconforming use of land is inapplicable to this present action, which does not concern a nonconforming use of land, but rather the nonconforming use of a structure. The Zoning Ordinance does contain a provision addressing the nonconforming use of a structure, providing, [a]ny nonconforming use of land or structure and any nonconforming structure shall lose whatever rights might exist to its continuation under this section if said use or structure shall be abandoned or not used for a period of two (2) years or more. Salem Zoning Ordinance Art. VIII, § 8-5(6) at p. 52. In any event, whatever time period is applied, I find that Mr. Copelas has made continuous use of the building to warehouse inventory and equipment for his laundry business. Mr. Copelass son also regularly visits the property during the week to either deliver or pick up inventory items which include linens, sheets, pillowcases, and bath towels. I thus reject the Tuckers argument that the Copelas building has lost its nonconforming use through discontinuation or abandonment.

I also reject the argument that under Article VIII, § 8-5(4) of the Zoning Ordinance, the Board exceeded its authority in granting a special permit to change one nonconforming use to another nonconforming use because the development of the building will require structural alterations. Section 8-5 does not concern the Boards authority to grant a special permit to an applicant who seeks to change a nonconforming use. Section 8-5 deals only with the continuation of a nonconforming use, plainly stating, the use may be continued so long as it remains otherwise lawful, subject to the following provisions

. (emphasis added) One of those provisions is § 8-5(4) which allows a property owner who does not intend any structural alterations to change one nonconforming use to another nonconforming use provided the Board finds the proposed use is equally appropriate or more appropriate to the district than the existing nonconforming use.

The Zoning Ordinance, however, does grant the Board the authority to issue a special permit to an applicant to change one nonconforming use to another nonconforming use even if structural alterations are planned. Article VIII is dedicated solely to issues arising from nonconformities, and § 8-6 specifically states: Notwithstanding anything to the contrary appearing in this ordinance, the board of appeals may grant special permits as authorized by section 5-3(j) and section 9-4 when the same may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent and purpose of this ordinance. Article V, § 5-3(j) states, the board of appeals may

grant special permits

for change, enlargement, extension or expansion of nonconforming lots, land, structures and uses, provided

[the change]

shall not be substantially more detrimental than the existing nonconforming use to the neighborhood

. Salem Zoning Ordinance at p. 21 (emphasis added).

In considering whether a special permit should be granted where structural alterations are necessary to accomplish a change of use, the Board may rely on factors favoring the grant such as the footprint of structure remaining the same, the lack of any increase in the structures nonconformity, and an overall improvement in the structures appearance. See Nichols v. Bd. of Zoning Appeal of Cambridge, 26 Mass. App. Ct. 631 , 634 (1988).

As a matter of law, the Board had the authority to grant a special permit to change one nonconforming use to another when structural alterations were necessary, and furthermore, the facts presented at trial substantiate the Boards decision. The redevelopment of the Copelas building into a six unit residence would improve the overall appearance of the structure, maintain its current footprint, comport with the residential character of neighborhood, and the result would present little, if any, detrimental impact to traffic, parking, or privacy concerns. No credible evidence was presented that would allow me to conclude that the Board acted arbitrarily or capriciously in granting the permit, and therefore I find no grounds to disturb its decision.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the plaintiffs appeal is DISMISSED in its entirety, WITH PREJUDICE. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

DONALD A. TUCKER, TINA M. TUCKER, AUGUSTINE P. SOUSA, III, ANN SOUSA, LAURA LEBLANC, JOSEPH B. SCHORK, RACHEL L. SCHORK, ANNE M. BACCARI, CHRISTINE MICHELINI, KRISTIN AMOS-GUIDO, PAUL GUIDO, D.L. COTE, CELIA M. ERWIN, PAMELA SCHMIDT, CRESENE SANGLAP, JOSEPH PATTI, JEANNE M. GARRAHAN and VIRGINIA WHITLEDGE v. ROBIN STEIN, REBECCA CURRAN, RICHARD E. DIONNE, BETH DEBSKI, BONNIE BELAIR, JIMMY TSITSINOS and ANNIE HARRIS as members of the Salem Zoning Board of Appeals, PETER COPELAS and LEWIS LEGON

DONALD A. TUCKER, TINA M. TUCKER, AUGUSTINE P. SOUSA, III, ANN SOUSA, LAURA LEBLANC, JOSEPH B. SCHORK, RACHEL L. SCHORK, ANNE M. BACCARI, CHRISTINE MICHELINI, KRISTIN AMOS-GUIDO, PAUL GUIDO, D.L. COTE, CELIA M. ERWIN, PAMELA SCHMIDT, CRESENE SANGLAP, JOSEPH PATTI, JEANNE M. GARRAHAN and VIRGINIA WHITLEDGE v. ROBIN STEIN, REBECCA CURRAN, RICHARD E. DIONNE, BETH DEBSKI, BONNIE BELAIR, JIMMY TSITSINOS and ANNIE HARRIS as members of the Salem Zoning Board of Appeals, PETER COPELAS and LEWIS LEGON