GARRETT DONLIN v. PAUL CALDWELL and THERESA CALDWELL.

GARRETT DONLIN v. PAUL CALDWELL and THERESA CALDWELL.

MISC 07-356274

November 21, 2013

Worcester, ss.

Long, J.

GARRETT DONLIN v. PAUL CALDWELL and THERESA CALDWELL.

GARRETT DONLIN v. PAUL CALDWELL and THERESA CALDWELL.

Long, J.

Introduction

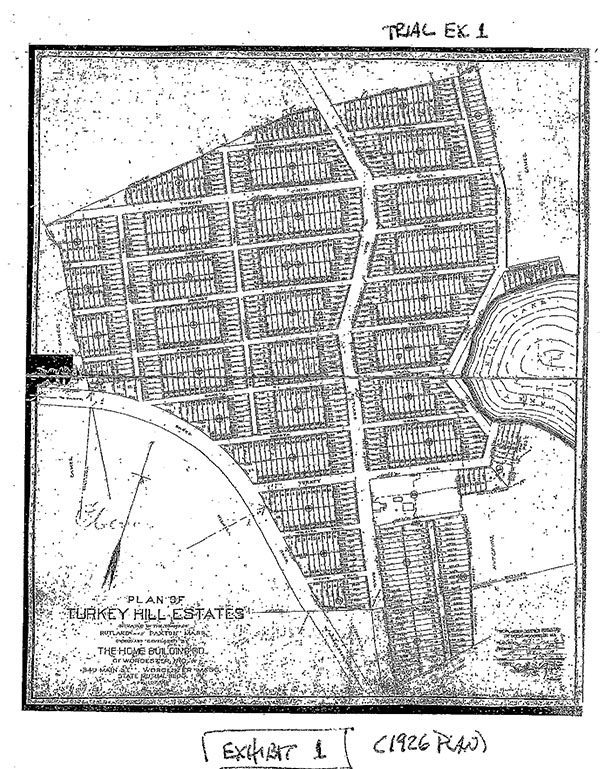

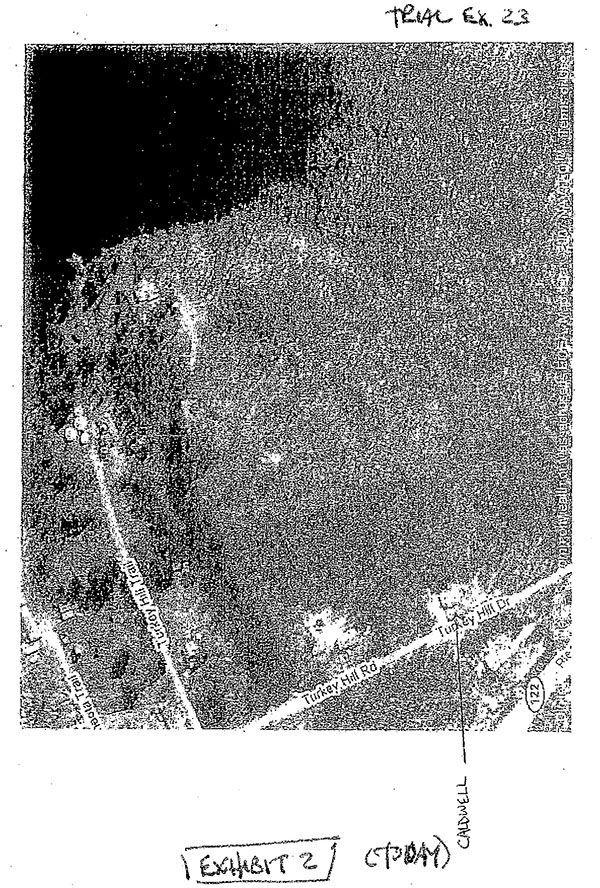

On June 10, 1926, the Home Building Co. of Worcester, Inc. filed a Plan of Turkey Hill Estates, situated in the Towns of Rutland and Paxton Mass. at the Worcester County Registry of Deeds (the plan). See Ex. 1. It is not, and never has been, an approved subdivision plan, nor does it reflect the current-day reality. The plan shows hundreds of tiny lots and a number of private roadways. With the exception of the main access route Rutland Road, now paved and re-named Turkey Hill Road nothing has developed in conformity with the plan. Most of the land is vacant. The land that has been developed a relatively small number of houses, mostly near the lake consists of lots grouped into larger, buildable parcels with homes generally begun as summer cottages that have since been winterized and expanded into year-round residences. Some of the plan roadways have been brushed out and rough-graded. Some have been graveled, in part. But most remain paper streets at best. [Note 1] One of those streets is Kiyi Trail, shown on the plan as a cross-way between Rutland Road and Potomac Trail. Its western half borders the defendants Paul and Theresa Caldwells property on the north, and has been used by the owners of that property since at least 1954 as their driveway, their storage and repair area for trucks, boats, snowplows and snowmobiles, and as a childrens play space, complete with basketball hoop, horseshoe pit, and picnic table. See Ex. 2 (aerial photograph) and Trial Exs. 30-38 & 51 (photographs, over time, of the driveway and the area behind it).

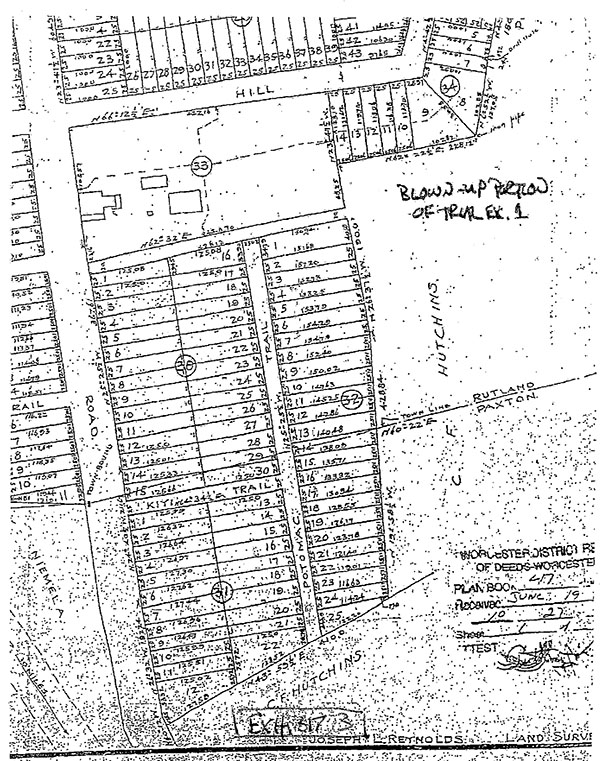

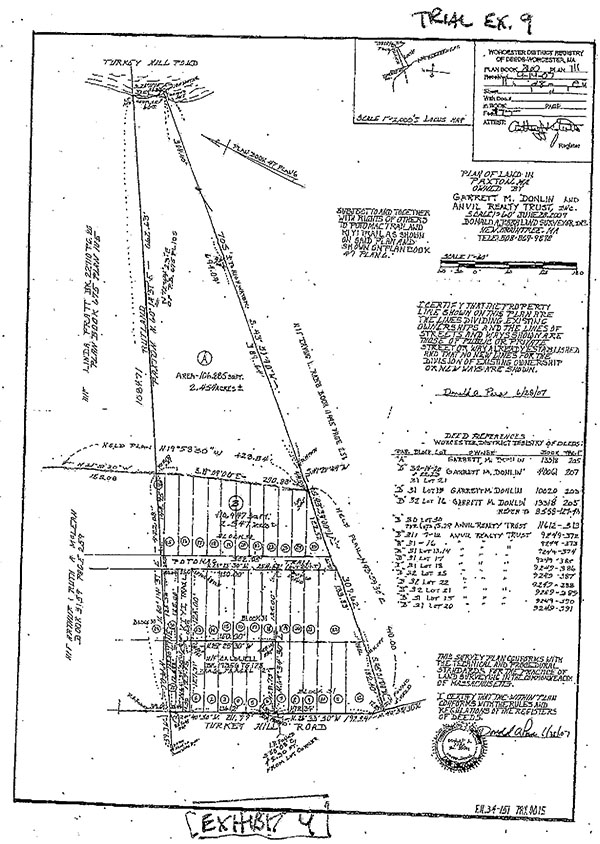

The Caldwells property is Block 31, Lots 1-6 on the plan, all in Paxton. [Note 2] See Ex. 3. Plaintiff Garrett Donlin, a developer, has purchased the remaining Paxton lots [Note 3] plus additional land to the east of the plan that borders the lake, all of which he has merged into a single parcel for development purposes. See Ex. 4. [Note 4] He wants to use Kiyi Trail to service and provide access to a single family residence and such structures and uses customarily accessory thereto to be located on that merged parcel. Plaintiffs Stipulation (Mar. 2, 2010). To do so would involve using one of the plan lots (Block 32, Lot 16) as a connecting roadway from his proposed lakeside residence to Kiyi Trail.

The issues presented are whether Mr. Donlin may use the western half of Kiyi Trail as an access route (the part occupied by the Caldwells driveway, parking, storage and childrens play area) and, if so, whether he can use it to access his non-plan land (parcel A). There is also a preliminary question the ownership of the record fee in that portion of Kiyi Trail which must be answered to determine if the proper parties are before the court when addressing the parties claims for relief.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived, with Mr. Donlin represented by counsel and the Caldwells representing themselves, pro se. Based on the evidence admitted at trial, my assessment of the weight, credibility and reliability of that evidence, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, I find and rule as follows.

Analysis

At issue is Mr. Donlins right of access over the western half of Kiyi Trail the portion immediately to the north of the Caldwells property, occupied by their driveway and the vehicles and other objects they park or store behind it. None of Mr. Donlins deeds contain an express easement to use Kiyi Trail, nor does the Caldwells deed expressly reflect the burden of such an easement. To the extent such an easement exists, it arises solely from the Turkey Hill Estates plan and the deed references to that plan a so-called common scheme easement. [Note 5] See Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 (2006). It is undisputed that Kiyi Trail appears on the plan and that each of the parties deeds conveyed their land by reference to the lot numbers on that plan. Those deeds do not, however, describe the properties as by, on, or bounded by Kiyi Trail, and do not refer to Kiyi Trail at all.

Kiyi Trail is shown on the plan as a cross-way between Rutland Road (the main route through the development, now paved and re-named Turkey Hill Road) and Potomac Trail. See Ex. 3. The western half of Kiyi Trail (the part at issue in this lawsuit) is bordered on the south by Block 31, Lots 1-6, owned by the Caldwells since August 30, 1995, and on the north by Lot 15 in Block 30, part of which is in Paxton, part in Rutland. The deeds to those properties from their once-common owner, Home Building Co. of Worcester, Inc. (the original developer, on whose behalf the plan was filed), did not reserve the fee in Kiyi Trail. Thus, under the Derelict Fee statute, the abutting properties own the record fee to its centerline on their side. G.L. c. 183, §58. [Note 6] This is the Caldwells to the south. But Mr. Donlin does not own the Paxton part of Lot 15 to the north.

Mr. Donlins claim of ownership to that land derives from a tax taking by the town of Paxton. [Note 7] The taking, and the judgment foreclosing the right of redemption, was to Paxton Assessors Map 9, Lot 1, described as approximately .51 acres of land (vacant). [Note 8] Paxton Assessors Map 9, Lot 1, is Block 31, Lots 7-12 on the plan 22,400 square feet, or .514233 acres. [Note 9] The Paxton part of Block 30, Lot 15 is designated Lot 1A on Assessor Map 9, with 5,000 square feet (.1148 acres) of its own clearly a different parcel than Lot 1 and thus remaining in its last owner of record, Louise Vetrano, or her successors in interest. [Note 10], [Note 11] For the reasons discussed below, the Caldwells may have a claim to some or all of this land by adverse possession. [Note 12] But because the record owner of that land (Ms. Vetrano) is not a party to the case, the merits of the Caldwells adverse possession claim against her ownership cannot be determined in this lawsuit. What can be determined is Mr. Donlins right of access over the part of Kiyi Trail owned by the Caldwells (the part abutting their property, to the centerline) and such part north of the centerline (owned of record by Ms. Vetrano) as the Caldwells and their predecessors have occupied. I thus turn to that question.

For purposes of this Decision, I assume without deciding that, at the time the Turkey Hill Estates plan was recorded (June 19, 1926), Kiyi Trail was intended as a common scheme easement for the use of Turkey Hill Estates property owners. [Note 13] Mr. Donlin, who bought his property in 1984, would now like to use Kiyi Trail in connection with his development plans. The issue thus becomes whether all rights to use its western half were abandoned and extinguished before he acquired his property ownership. The applicable law, and the facts as I find them after trial, are as follows.

An easement is extinguished by grant, release, abandonment, estoppel or prescription. Delconte v. Salloum, 336 Mass. 184 , 188 (1937). Whether there is an abandonment is ordinarily a question of intention. Id. Non-use does not of itself produce an abandonment no matter how long continued. Id. (emphasis added). But abandonment can be inferred from the surrounding circumstances and conduct of the parties; failure to protest acts which are inconsistent with the existence of an easement, particularly where one has knowledge of the right to use the easement, permits an inference of abandonment. The 107 Manor Avenue LLC v. Fontanella, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 155 , 158-159 (2009).

A use of the servient tenement, to have the effect of extinguishing an easement in it, must be wrongful. To be wrongful it must be of such a nature as to give rise to a cause of action in favor of the owner of the easement. To do this it must either interfere with a use under the easement or have such an appearance of permanency as to create a risk of the development of doubt as to the continued existence of the easement. Delconte, 336 Mass. at 189 (internal citations and quotations omitted). [T]he actions of the adverse possessor must be irreconcilable with use by any other right holder. In such a situation, the adverse possessor cannot merely make use of the way as others might; she must make exclusive use of the way that prevents all others from exercising their rights over the way. Gerry v. Biviano, 56 Mass. App. Ct. 1112 (2002), 2002 WL 31698180 at *2 (Rule 1:28 disposition). The maintenance of a parking area in the easement can meet this test, so long as it existed continuously and the parking obstructed the way entirely. Id. at *3. See also Delconte, 336 Mass. at 189 (establishment and habitual use of permanent parking area); Sindler v. William M. Bailey Co., 348 Mass. 589 , 593 (1965) (acquiescence in construction of fence and placing of chain across entrance for 35 years warrant an inference that [the benefited party] has abandoned its rights to the easement in question.); Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 492-493 (1933) (Physical obstructions on the servient tenement, rendering user of the easement impossible and sufficient in themselves to explain the nonuser, combined with the great length of time during which no objection has been made to their continuance nor effort made to remove them, are sufficient to raise the presumption that the right has been abandoned and has now ceased to exist.); Skipper Realty LLC v. Jerrys Auto Service Inc., 84 Mass. App. Ct. 1104 (2013), 2013 WL 3778969 at *1 (Rule 1:28 disposition) (plaintiffs acquiescence in servient landowners use of way as parking area for tenants, preventing its use as access to plaintiffs property, combined with later erection of fence, is powerful evidence of abandonment). [Note 14]

The testimony earliest in time regarding Kiyi Trail came from Roland Veaudry, Jr., whose family moved into what is now the Caldwell house in June 1954 when Mr. Veaudry was 14. [Note 15] Mr. Veaudrys parents bought the property on an installment plan, and received formal title on May 27, 1960 (Block 31, Lots 3-6) and July 28, 1967 (Block 31, Lots 1 & 2). Mr. Veaudry later acquired the property from his parents and subsequently sold it to the Caldwells on August 30, 1995.

The Caldwell house is just a few feet off the northern boundary of Block 31, Lot 1, and its driveway, made of concrete, goes down the center of Kiyi Trail as far as the rear of the house. There are approximately 30 feet between the end of the driveway and the rear boundary of the property. According to Mr. Veaudry, the driveway was concrete in 1954 (it is still concrete) and in the same location as it is today. There was a garage to its right when the Veaudrys moved in, which the Veaudrys used as a workshop. [Note 16] The Veaudrys and their visitors parked their cars on the driveway. [Note 17] This effectively blocked its use by others, and Mr. Veaudry testified unequivocally that, throughout the period of their ownership, no one other than his family used the driveway or traveled through the area behind it, either by vehicle or on foot, without his familys permission. [Note 18] He would occasionally see people in the woods, but they used another route to get there. [Note 19] The thirty-foot area behind the driveway to the rear boundary of the property was used to park more cars and trucks and store a snowplow, boat, trailer, and childrens toys. There was also a picnic table in that location, used regularly for summer meals. A horseshoe pit was installed on the western side of the driveway. None of these uses was ever challenged or disturbed by anyone while the Veaudrys were there.

The Caldwells have used the driveway and the area behind it in identical fashion since they moved in, just as continuously, with a similar or greater number of vehicles, trailers, toys, and other large objects occupying that space. In addition, Mr. Caldwell repairs cars there. The Caldwells have also placed their own picnic table near the back boundary and added a basketball hoop at the end of the driveway. All this blocks the width of Kiyi Trail to the treeline on its side. [Note 20] With the exception of Mr. Donlin in the incidents described below, the Caldwells too have never seen anyone attempt to access, or come from, the area behind their property using their driveway or any other part of Kiyi Trail.

Mr. Veaudry testified that there were no trails behind the house when his family lived there (1954-1994/5), just briars. The eastern part of Kiyi Trail was perhaps passable by foot though the briars, but not by vehicle. Whatever road grading had been done in the area, primarily of Wichita and Potomac Trails, [Note 21] long pre-dated his familys ownership (a horse-drawn grader had been left in the woods by the side of Potomac Trail but, so far as he could tell, never moved), [Note 22] and everything was now overgrown. The Caldwells witnesses gave similar testimony, which I credit. [Note 23] No passable trail existed on the eastern part of Kiyi Trail from at least 1954 up until the time Mr. Donlin began brushing it out in the mid-1980s. [Note 24] In any event, the parked cars, trucks, trailers, boats, snowmobiles and other objects in the Veaudry/Caldwell driveway and in the 30 feet between the driveway and the rear boundary of their property have blocked the use of the western portion of Kiyi Trail (the part in dispute) as any kind of access route openly, notoriously, continuously, exclusively, and adversely since at least 1954.

Mr. Donlin argues otherwise, based on his own testimony, the testimony of his wife, the testimony of James Perroni, and the testimony of Pauline Nishan, now 80, and a neighborhood resident for 48 years at the time of trial. [Note 25]

Ms. Nishan and her husband were long-time friends of the Veaudrys. Indeed, Mr. Nishan and Mr. Veaudry went to school together, and Mr. Nishan was a frequent visitor to the Veaudry house. The Nishans lived on the opposite side of Rutland Road/Turkey Hill Road, south of the Veaudry property, and would occasionally walk to the lake from their home (he apparently liked to fish) and sometimes more generally through the woods. Ms. Nishan recalls them going to the lake by way of Turkey Hill Trail (the direct route from their home to the lake, see Ex. 1) and, when walking in the woods, using the long road likely either Wichita Trail, Potomac Trail, or both, relatively clear at that time. [Note 26] Their walks became more frequent when they bought Block 32, Lot 2 in the mid-1980s a lot in Rutland on the east side of Potomac Trail, one lot south of Wichita Trail, see Ex. 1 but not much more frequent. The Nishans never did anything with the lot, and Ms. Nishan considered the investment a nightmare.

Beyond this, Ms. Nishans testimony was vague and unreliable. She testified about visiting the Veaudrys and, on one occasion, asking them to move their cars so that she and her husband could drive to what she recalls as a pathway behind their house. But I do not believe this. If the Nishans were driving to their lot or the lake, they would have taken their usual, easier routes Wichita Trail or Turkey Hill Trail. The eastern half of Kiyi Trail was never more than rough graded. Mr. Veaudry, who lived next to it during the same time referenced by Ms. Nishan, testified it was overgrown and impassable filled with briars. Even Mr. Donlins wife Deborah conceded that it required a four-wheel drive vehicle to get through when she first saw it in the mid-1980s.

Ms. Nishan also testified to another occasion on which, she says, she and her husband drove to the house after the Caldwells bought it and told the Caldwells there was a right of way through their driveway. Ms. Caldwell had no memory of this, and I find it difficult to believe. In any event, according to Ms. Nishan, Ms. Caldwell told them they could not drive there and, when Ms. Nishan looked at the woods behind the house, she had to agree that the route was not driveable. The Nishans did not attempt to walk there because of the Caldwells dogs. The Nishans never asked for the dogs to be taken elsewhere.

Ms. Nishan said that her husband and grandchildren would occasionally walk through the driveway on their way to the lake or to go camping in the woods when the Veaudrys owned the house, but I question this. It was not apparent that she had any personal knowledge of this (she did not accompany them). And again, if they did walk through the driveway when the Veaudrys lived there, they did so as friends, with permission. [Note 27] No one else walked that way, and the Veaudry/Caldwell cars and other vehicles parked there blocked any vehicular use. [Note 28]

As noted above, an easement is extinguished when an adverse, irreconcilable, apparently permanent interfering use is made of it by others, and the easement holders acquiesce. See Delconte, The 107 Manor Avenue LLC, Gerry, Sindler, Lund and Skipper Realty, supra. I find that that is what happened here. The easement was extinguished and abandoned by the time Mr. Donlin purchased his property in 1984. Extinguishment and abandonment by blockage occur on the portion blocked. Id. Here, that portion is the entire width of the driveway, all the way to the treeline to its left. Brief interruptions in the blocking those few occasions when a car was driven elsewhere, temporarily leaving a potential corridor open did not end the extinguishment since the area occupied by the cars and other objects had an appearance of permanency as to create a risk of the development of doubt as to the continued existence of the easement, Delconte, 336 Mass. at 189, and, prior to Mr. Donlin, no one challenged the blockage, The 107 Manor LLC, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 158-159. The question then becomes whether the extinguishment ended or was abandoned, and the easement somehow reinstated, after Mr. Donlin acquired his property. I find that it was not.

Mr. Donlin testified that he bought his land in 1984 and soon thereafter began brush hogging all the ways on that land that were shown on the Turkey Hill Estates plan. His purchases included not only the land shown on Ex. 4, parcels A and B, but also large tracts to the north near the lake, owned by the Hutchins estate, that had never been part of Turkey Hill Estates. Some of the ways on the plan, he says, although overgrown with bramble bushes, were relatively easy to visualize. [Note 29] Others, he admitted, were difficult to locate, and Potomac Trail was one of these. In Mr. Donlins words, it was hard to figure out where it was, even after seeing the stone walls and pillars referenced above. He claims he was first on the eastern half of Kiyi Trail in 1984, preparing the land for surveying, [Note 30] but was not frequently there afterwards because the main access way into his land was Wichita Trail and he spent most of his time at the property to its north on the lake the former Hutchins land to the east of Turkey Hill Estates. See Ex. 1. He says, though, that he walked the entire length of Kiyi Trail, including across the Veaudrys driveway out to Turkey Hill Road, at least once or twice a year when the Veaudrys owned the property.

Over time, Mr. Donlin divided the land he bought into larger parcels and sold them off. The ones already sold are those on or near the lake (the former Hutchins property), leaving him presently with only parcel A and parcel B as shown on Ex. 4. Because of his prior sales, he no longer has access over Wichita Trail (a self-created situation) and needs to use either Kiyi Trail or a newly created way from Turkey Hill Road for such access. He has constructed such a new access way during the course of this litigation and currently uses it. [Note 31] He would prefer, however, to use Kiyi Trail. Its eastern half (the portion on his land) became passable by tractor after his initial brush hogging, and he testified that he has returned to brush hog it again every five years or so. [Note 32] He claims to have accessed Kiyi Trail on these occasions by using the Veaudry (now Caldwell) driveway, maneuvering his small tractor around the cars and other objects, but this could only have been sporadic at best (according to his testimony, every five years or so), and is inconsistent with, or at least highly modified by, his testimony regarding his need to ask for cars and other objects to be moved on at least two of those occasions.

These occasions were as follows. Mr. Donlin spoke with Ms. Veaudry (Mr. Veaudrys mother) sometime after 1984, asking her to move her car which was parked in the driveway, thus blocking it. She moved her car as he requested. Clearly this was permissive, and not any kind of acknowledgement that the driveway should remain unblocked, since her car was again in the driveway when he next returned some years later and once again requested it be moved so he could get from the woods to Turkey Hill Road. She once more agreed, and again I find that this was wholly permissive on her part, not a recognition or acknowledgement that Mr. Donlin had any right to insist on its moving. As Ms. Nishan testified, Ms. Veaudry was a nice person.

Mr. Donlin came again after the Caldwells had purchased the property. He and his wife would sometimes walk in the area, but did not cross the Caldwell property or walk on the driveway because of the Caldwells dogs. He claims to have driven over the driveway with nothing blocking it, but this appears to be the occasion on which he had to move the Caldwells picnic table to do so. He claims also that the equipment used to conduct the percolation tests on parcel A and parcel B used the Caldwells driveway, but I am not persuaded that there were any occasions on which the driveway and the area immediately behind it were completely unblocked (Mr. Donlin admitted that there was always stuff there), and am sure that these were times when the Caldwells were away and thus unaware of the intrusion. The pictures Mr. Donlin introduced into evidence at trial clearly show the Caldwells vehicles and other objects blocking the driveway and the land behind the western half of Kiyi Trail with no way to get through without things being moved. The Caldwells confronted Mr. Donlin on the one occasion they saw him trying to use their driveway and went to the police about it.

Mr. Donlins wife Deborah testified briefly about her observations of Kiyi Trail. As previously noted, she conceded that, even after her husband brush-hogged its eastern half, it was passable only by a four-wheel drive vehicle. She claims to have driven over the driveway while the Veaudrys owned the property with nothing blocking her way, but I am not persuaded she did so [Note 33] or, at best, did so on more than one occasion and then only with great difficulty. [Note 34] As her husband testified, there was always stuff there.

Mr. Donlin also offered the testimony of his contractor, James Perroni, who assisted with the percolation tests referenced above. Mr. Perroni recalls at least one occasion on which he drove over the driveway to the brush-hogged pathway on the eastern half of Kiyi Trail behind it, [Note 35] but did so only at Mr. Donlins direction and only after Mr. Donlin had preceded him. He thus could not say whether Mr. Donlin needed to move anything for them to get there, or what it took to move those things. He did not recall seeing anyone at the Veaudry/Caldwell house when he went down the driveway.

I have gone through the testimony and exhibits in detail to assure the parties that I have considered it all, thoughtfully and carefully. But it can be summarized, succinctly, as follows. Kiyi Trail is a way on a plan, never constructed in accordance with that plan, to serve lots never developed in accordance with that plan. Only recently (Mr. Donlin), and in a way at variance with the plan (by combining and reconfiguring lots and adding property from elsewhere), has anyone asserted a need, or even a desire, to use the portion of Kiyi Trail at issue in this case. Over half a century ago, a concrete driveway was put on that part of Kiyi Trail (its western half) to serve the house now owned by the Caldwells. It did not extend any further than the garage, thirty feet short of the property line, and it was not roughed out or developed any further than the garage, showing its intent to be used as a driveway, and a driveway only, not the initial part of a connecting roadway. Whatever was done to Kiyi Trail in the woods behind stopped at the Caldwells rear property line.

For more than 50 years, the concrete driveway and the area behind it have been used as a driveway and storage area for the Caldwell house, solely and exclusively. The residents have parked their cars there. They have stored their boats, trucks, snowmobiles and snowplows there. They have put their childrens toys and picnic tables there, and their children have played there freely. All of this has blocked its use, completely, and no one went there, to their knowledge, who did not have their permission and cooperation. During the course of that 50 years, on no more than a handful of occasions, people have walked over the driveway to the woods behind. During the course of that 50 years, on even fewer occasions, an all-terrain vehicle has accessed the woods using the driveway, almost always needing to move things to get there. Permission was generally asked and given. When it was not, the intrusions either took place when the Veaudrys or Caldwells were elsewhere and unknowing or, if they were there, resulted in an argument and then a call to the police.

Because I find the easement extinguished, I need not reach the remaining issue in the case whether, if the easement still remained, it could be used to access Mr. Donlins parcel A the part of his land, sought to be served by the easement, that was never part Turkey Hill Estates as shown on the plan from which the easement is implied. I do so, however, for the sake of completeness. The answer is no. Any such use would overburden it. Private ways are confined in their use to the purposes for which they are granted, and cannot be further extended by the grantees....one who has a right of way appurtenant to a specified lot of land cannot lawfully use it to reach another parcel owned by him to which it is not appurtenant. Matthews v. Planning Bd. of Brewster, 72 Mass. App. Ct. 456 , 465-466 (2008). Here, the easement arose solely from the plan and thus solely benefited the lots on that plan. See Reagan, supra. It cannot be extended further.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the plaintiffs claims are DISMISSED IN THEIR ENTIRETY, WITH PREJUDICE, and it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that whatever easement existed on the western part of Kiyi Trail as shown on Ex. 1, appurtenant to any part of the plaintiffs land, has been abandoned and extinguished across the width of the defendants driveway as far as the treeline to its north.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

exhibit 4

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] Paper streets are ways that appear on recorded plans but have never been built. See Gates v. Planning Bd. of Dighton, 48 Mass. App. Ct. 394 , 396-397 (2000).

[Note 2] Exs. 1 & 3 show the town line.

[Note 3] I say purchased, but there are title issues with respect to a number of the lots, making it unclear whether Mr. Donlin owns those lots or not. See trial testimony of Jeremy OConnell, Esq. Only one such lot is material to the adjudication of this case the Paxton portion of Block 30, Lot 15 (the town line bisects the Lot). Because of that, I address the title to that Lot and that Lot only, and need not and do not adjudicate the title to any others. For purposes of this Decision, I assume that Mr. Donlin owns the remaining lots.

[Note 4] Mr. Donlins plan lots all of the lots on the Paxton portion of the plan except for the Caldwells Lots 1-6 and, as discussed below, the Paxton portion of Block 30, Lot 15 arelabeled B on Ex. 4, and the additional land, east of the plan, between those lots and the lake is labeled A.

[Note 5] Mr. Donlin did not claim, nor did the evidence support, a prescriptive easement. Such an easement requires proof of open, uninterrupted and adverse use, by the claimants and/or their predecessors in title, of the land at issue, without its owners permission, for a period of at least twenty years. Ivons-Nispel v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 761-762 (1964); Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870) (appurtenant prescriptive easement over neighboring land established by twenty years or more of open, adverse and continuous use by the property owner and her predecessors [her late husband and his father]); Garrity v. Sherin, 346 Mass. 180 , 182 (1963) (for private easement it is required that the plaintiff prove open, uninterrupted and adverse use for a period of not less than twenty years by the claimant and his predecessors in title); Stagman v. Kyhos, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 590 (1985). As apparent from the discussion of the evidence below, there was no such showing.

[Note 6] As the statute provides:

Every instrument passing title to real estate abutting a way, whether public or private, watercourse, wall, fence or similar linear monument, shall be construed to include any fee interest of the grantor in such way, watercourse or monument, unless (a) the grantor retains other real estate abutting such way, watercourse or monument, in which case (i) if the retained land is on the same side, the division line between the land granted and the land retained shall be continued into such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (ii) if the retained real estate is on the other side of such way, watercourse or monument between the division lines extended, the title conveyed shall be to the center line of such way, watercourse or monument as far as the grantor owns, or (b) the instrument evidences a different intent by an express exception or reservation and not alone by bounding by a side line. G.L. c. 183, §58.

[Note 7] See trial testimony of Jeremy OConnell, Esq.

[Note 8] See Trial Ex. 8 and the record in Town of Paxton v. Louise Vetrano, Land Court Case No. 83 TL 69919.

[Note 9] See Trial Ex. 18 (Paxton Assessors Map 9).

[Note 10] Mr. Donlin is not one of Ms. Vetranos heirs or other successors. His claim of ownership to the land bordering the north of the western half of Kiyi Trail is based solely on the town of Paxtons taking of the land shown on Assessors Map 9, Lot 1 for unpaid taxes and the subsequent foreclosure of the right of redemption. See trial testimony of his title examiner, Jeremy OConnell, Esq.

[Note 11] The Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum reflects an agreement by the plaintiff and the pro se defendants that, with the exception of Lots 1-6, the Plaintiff is the owner of all the lots in Paxton shown on the Plan (Donlin Land), including the lots abutting so much of Kiyi Trail as is between the Plaintiff and the Defendants land. Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum at 3,¶2(a). It is not clear, however, what (if any) investigation was done or legal advice sought by the defendants before making that agreement. In any event, the court is not bound by stipulations if it is clear...upon the agreed and uncontrovertible facts that the stipulation is incorrect. See Derderian v. Union Market Natl Bank of Watertown, 326 Mass. 538 , 539-540 (1950). Such is the case here, for the reasons explained above. Note too that the plaintiffs title witness, attorney OConnell, also identified problems with other parcels covered by the stipulation, calling them into question as well. See n. 3. If the plaintiff has additional evidence, not part of the trial record, that shows my conclusion wrong, he may timely move for reconsideration of this finding.

[Note 12] See, e.g., the parties agreement that the disputed area has been used as a driveway for approximately 50 years by the defendants (14 years) and the previous owner or residents at 4 Turkey Hill Road, Paxton, Massachusetts [the defendant Caldwells house]. Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum at 3, ¶2(c). The evidence did not include a survey of the on the ground location of the Caldwells driveway or the areas to its north or rear that have been used by the Caldwell property owners for additional parking, storage, etc. as described below. It is clear from the evidence that those uses extended at least to the centerline, but the precise extent (if any) that they extended beyond the centerline is unknown. Such beyond the centerline use would be the basis of an adverse possession claim by the Caldwells against Ms. Vetrano.

[Note 13] The standard for finding a common scheme easement is as follows:

The origin of an implied easement whether by grant or by reservation must be found in a presumed intention of the parties, to be gathered from the language of the instruments when read in the light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge which the parties had or with which they are chargeable. A plan referred to in a deed becomes a part of the contract so far as may be necessary to aid in the identification of the lots and to determine the rights intended to be conveyed. Further, it is well established that where land is conveyed with reference to a plan, an easement is created only if clearly so intended by the parties to the deed. The burden of proving the existence of an implied easement is on the party asserting it. Reagan v. Brissey, 446 Mass. 452 , 458 (2006).

I have assumed an original intent to make Kiyi Trail a common scheme easement, without delving further, because the question is moot. As detailed below, the evidence shows that whatever easement may once have existed in the western half of Kiyi Trail has long since been extinguished and abandoned, before Mr. Donlin acquired his property. But a truly hard look might indicate there was never any actual intention to make the western half of Kiyi Trail an easement at all. As the cases hold, [i]n determining the intent, the entire situation at the time the deeds were given must be considered. For example, whether the ways in question merely existed on paper, or were then constructed on the ground; whether they were then actually used as appurtenant to the granted premises; or whether they were remote or in close proximity. Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 755 (1945). As detailed below, when actual on the ground construction took place on the western half of Kiyi Trail (by an officer of the developer, no less), it was solely to build a driveway to the now-Caldwell home, thirty-feet short of the rear property line, without any connection to anything further and with parking behind the driveway blocking any such connection. The land potentially accessible from Kiyi Trail has never been developed, see Ex. 2, and even under Mr. Donlins proposal will be combined and configured totally differently than set out on the plan. Compare Ex. 1 with Ex. 4. Eliminating it from the overall scheme of the development would not materially change that scheme. Unlike the roads to the lake (e.g., Turkey Hill Trail) and the road to the former club site (Wichita Trail; the club was in the buildings shown on Block 33), Kiyi Trail does not lead anywhere in particular. So far as the record shows, no one other than Mr. Donlin has ever claimed reliance on Kiyi Trails existence or any need to use it, and even he currently uses a different access route.

[Note 14] Contrast First Natl Bank of Boston v. Konner, 373 Mass. 463 , 467 (1977) (noting that abandonment is not proved by proof of acts which interfere with use of the easement only temporarily, or only in part and that mere failure to clear a right of way of its natural cover of trees and brush is not sufficient for abandonment) (internal citations and quotations omitted)

[Note 15] The record does not indicate when the house and driveway were built. Mr. Veaudry testified that the owner before his parents was a Mr. Crocker (an officer of the Home Builders company), who rented it to the White family its occupants immediately prior to the Veaudrys occupation.

[Note 16] The garage has since been renovated and incorporated into the house as additional living space.

[Note 17] Mr. Veaudry acquired his first car at age 16 (in 1956), and his younger brother a few years later. Their father always had a car and other vehicles, and their mother had her own car from the mid-sixties onward.

[Note 18] Mr. Veaudry was able to testify to this from his direct personal knowledge. He lived on the property as a teenager, visited regularly while he was in the service, spent his early married years in the house, and then returned frequently thereafter to visit his parents (until his father passed away) and then his mother, who lived in the house until 1994. As previously noted, the house was sold to the Caldwells in 1995.

[Note 19] He believed they were employed by Mr. Hutchins, who owned land south and east of Turkey Hill Estates, see Ex. 1, and purchased Block 32 Lot 16 (on the east side of Potomac Trail) in 1930. If they were going to the woods or lake to the east of the Veaudry (now Caldwell) property, the route they likely took was Rutland Road/Turkey Hill Road onto Wichita Trail, and then from Wichita Trail to Potomac Trail, or directly onto Potomac Trail from Mr. Hutchins land to the south. See Ex. 1.

[Note 20] See, e.g., Trial Exs. 30 (Veaudry-era) & 50 (Caldwell-era), showing the treeline to the north (on the left of the driveway). As previously noted, the northern edge of the blocked area (essentially to the existing treeline) has not been surveyed. It is beyond the centerline of Kiyi Trail, but precisely how much beyond is unknown. Since Kiyi Trail is marked as 25 feet wide on the plan and the driveway is more than wide enough to park two vehicles side by side with space to open their doors, it is doubtful that much, if any, of Kiyi Trail is unblocked, or was unblocked, dating back to 1954.

[Note 21] There are remains of a stone wall and pillars at the intersection of Wichita Trail and Potomac Trail, and the remains of a second stone wall and pillars at the entrance into Block 32, Lot 16. There is nothing similar at Kiyi Trail (no walls, no pillars), or anyplace else. Based on the 1930 deed from Home Building Company conveying Block 32, Lot 16 to Charles Hutchins and Mr. Hutchins ownership of lakeside parcel A at that time, Mr. Donlin contends that the walls and pillars in those two locations marked an intended access route to Mr. Hutchins property by the lake, never actually developed. This route would have gone from Rutland Road (now Turkey Hill Road) down Wichita Trail, taken a right at its intersection with Potomac Trail through the pillars there, and then proceeded down Potomac Trail as far as the pillars at the entryway to Lot 16, turned left at those pillars into that lot, and proceeded through that lot to the lakeside land. It would not have involved any use of Kiyi Trail, and is consistent with the use of Wichita Trail and Potomac Trail as the sole intended access route to Block 32 Lots 1-25, Block 30 Lots 16-30, and Block 31 Lots 13-22 and the abandonment of any scheme to use Kiyi Trail.

There is some evidence of past grading on the eastern half of Kiyi Trail (what may have been an attempt at leveling a few inches of slope near a tree), but nothing to indicate that it ever extended into the western half (the area in dispute).

[Note 22] Its rusted remains are still there. Not far away are the rusted remains of the front end of a car, dumped there at some point in the past. No evidence was offered of who dumped the car parts and, because its unlikely that an owner or developer would do so, they were probably dumped by vandals seeking an isolated, out-of-the-way place to get rid of them.

[Note 23] See not only the testimony of Mr. Veaudry and Ms. Caldwell, but also the testimony of Karen Sutkus, Mr. Caldwells sister, who recalled trying to walk through the woods behind the house to the lake and finding it too overgrown.

[Note 24] Mr. Donlin has brushed-out the eastern part of Kiyi Trail under a claim of ownership pursuant to the Derelict Fee statute (the ownership of its abutting lots). As previously noted, for purposes of this Decision, I assume he owns them. In any event, the Caldwells (who do not claim such ownership) have no standing to object.

[Note 25] Mr. Donlin also offered the testimony of his surveyor, Donald Para, but Mr. Para added nothing important to the case. His observations of the eastern part of Kiyi Trail as roughed out like a cart road came after Mr. Donlin had brushed it out in preparation for its survey. His brief walks on the Caldwell driveway and property the western part of Kiyi Trail at issue in this case were done in search of monuments in connection with that survey and thus were neither a trespass nor in any way adverse to the Caldwells claims of exclusive use and possession of that area. See G.L. c. 266, §120C. They also apparently took place when the Caldwells were not at the house.

[Note 26] See n. 21, supra. As Mr. Donlin testified, by the time he first saw Potomac Trail in 1984, it was overgrown to such an extent that it was difficult to see where it was located. See discussion below.

[Note 27] Ms. Nishan admitted there were no such walks during the Caldwells ownership. They were not friends of the Caldwells, and the Caldwells dogs kept outsiders away.

[Note 28] Patricia Miller, who has lived and worked from her home on the other side of Rutland Road (now Turkey Hill Road) for over 27 years, can see the Caldwell house from her windows and sliding glass doors. She testified that she has seen strangers on the Caldwell property only twice in that time, and it was Mr. Donlin or his wife on both occasions. Ms. Caldwell was equally unequivocal. She is almost always at the house with her young children and, except for Mr. Donlin on the occasion she called the police (see discussion below), never saw anyone attempting to use their driveway or backyard for access to or from the woods behind their house. Mr. Donlin argues that there may have been times when all the cars were gone and people could have walked or driven there, but there was no evidence of any actual use, much evidence to refute it, and it is speculation at best. As noted above, people do not typically walk or drive on what is clearly someone elses driveway, directly under the windows of the house, to get to woods filled with brambles.

[Note 29] But not so easy that he believed a formal survey was unnecessary. Such a survey was conducted. Indeed, he claims he first saw the location of Kiyi Trail when preparing for the survey.

[Note 30] He testified that it was overgrown until he brush-hogged it.

[Note 31] This new way is pictured in Trial Ex. 39.

[Note 32] Passable is a relative term. As the photographs show, the eastern half of Kiyi Trail, even cleared and brush hogged, is two dirt tire tracks down a narrow, tree-hemmed channel. If it was ever cleared to a 25 foot width, that day was long ago. There are a number of tall trees, clearly decades old, within that width. See, e.g., Trial Exs. 46 & 54.

[Note 33] She would have had no reason to drive there. The land behind the Veaudry/Caldwell property was vacant, and the development that was occurring was taking place to the north by the lake and accessed by the Donlins over Wichita Trail.

[Note 34] In any event, the issue is moot since I find that any easement that existed was extinguished and abandoned before Mr. Donlin purchased his properties in 1984.

[Note 35] He was vague about the route he took the other times he was there. He may have been on the driveway on one or more of those occasions, or may have taken a different route.