Introduction

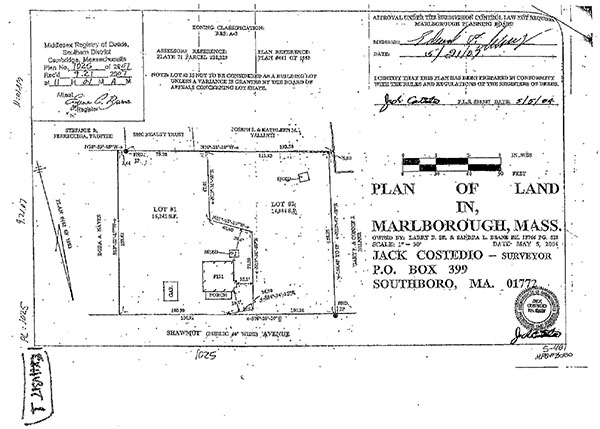

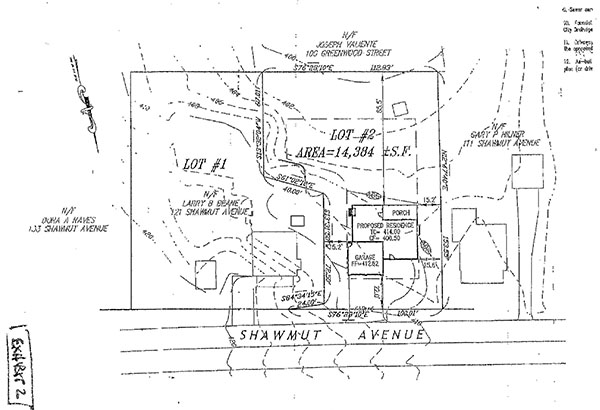

Plaintiffs Gary and Connie Hilner live next to the defendants Larry and Sandra Beanes property on Shawmut Avenue in Marlborough a dense, in-town neighborhood of small homes on small lots. By 2007 ANR plan, the Beanes divided their property into two lots, Lot #1 and Lot #2. See Ex. 1. Lot #1 contains the Beanes pre-existing house. Lot #2 is vacant except for a small shed and, without a variance, is not a separate buildable parcel because it does not comply with the lot shape requirements in the Citys zoning ordinance. The Beanes obtained such a variance from the defendant zoning board of appeals and propose to construct a single family residence on Lot #2 for their son and his family. See Ex. 2. The result would be two houses on land that previously had only one, with the new house located immediately next to the Hilners and over seventy feet closer than the existing one. Id.

The Hilners timely appealed that variance to this court pursuant to G.L. c. 40A, §17. Notice of the action and a copy of the complaint were timely given to the City clerk. The defendants were timely served, and an affidavit of service timely filed. Both the complaint and the notices correctly referenced the parties names, addresses, the variance (by date), the court and docket number where the appeal had been filed, and the grounds of the appeal. None, however, attached a copy of the variance decision itself. See G.L. c.40A, §17.

The case thus presents three issues. First, was the failure to attach a copy of the variance decision to the complaint as originally filed and served fatal to the Hilners appeal? If so, their appeal must be dismissed and the variance decision stands. If not, the case proceeds to the second question: was the variance properly granted? i.e., did it meet the requirements of G.L. c. 40A, §10? If so, the variance must be affirmed on the merits. If not, the third and final issue is reached and becomes decisive: do the Hilners have standing to challenge the variance? If they have such standing, the variance must be vacated. If they do not, their appeal must be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction and the variance decision stands.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the evidence admitted at trial, my assessment of the weight, credibility and reliability of that evidence, and the reasonable inferences I draw therefrom, I find and rule as follows.

Analysis

I begin with the threshold question. Is the Hilners failure to attach the board decision to their notices and complaint fatal to their appeal? [Note 1] The Beanes contend that it is, citing the following language in G.L. c. 40A, §17: Any person aggrieved by a decision of the board of appeals...may appeal [to the courts identified] by bringing an action within twenty days after the decision has been filed in the office of the city or town clerk...The complaint shall allege that the decision exceeds the authority of the board or authority, and any facts pertinent to the issue, and shall contain a prayer that the decision be annulled. There shall be attached to the complaint a copy of the decision appealed from, bearing the date of filing thereof, certified by the city or town clerk with whom the decision was filed. G.L. c. 40A, §17.

Failure to commence the appeal within twenty days after the decision is filed with the city or town clerk is fatal. That requirement is jurisdictional, Iodice v. Newton, 397 Mass. 329 , 333-334 (1986), and policed in the strongest way, Pierce v. Bd. of Appeals of Carver, 369 Mass. 804 , 808 (1976). Failure to file notice of the appeal with the city or town clerk within that same twenty day period is likewise fatal, due to the public interest in assuring that there is a timely record in the city clerks office giving notice to interested persons that the decision of the board of appeals has been challenged and may be overturned. See OBlenes v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Lynn, 397 Mass. 555 , 557-558 (1986) (internal citations and quotations omitted). But not all errors in the procedures under § 17 require dismissal; timely institution of an appeal under § 17 should be held a sine qua non, while other steps in the carrying out of the appeal should be treated on a less rigid basis. Konover Management Corp. v. Planning Bd. of Auburn, 32 Mass. App. Ct. 319 , 323 (1992) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

The standard for evaluating such problems of procedural compliance, id. at 323, n. 8, is set forth in Schulte v. Director of the Div. of Employment Sec., 369 Mass. 74 (1975):

Sloppiness in following a prescribed procedure for appeal is not encouraged or condoned, but at the same time a distinction is taken between serious missteps and relatively innocuous ones. Some errors or omissions are seen on their face to be so repugnant to the procedural scheme, so destructive of its purposes, as to call for dismissal of the appeal. A prime example is attempted institution of an appeal seeking judicial review of an administrative decision after expiration of the period limited by a statute or rule...With respect to other slips in the procedure for judicial review, the judge is to consider how far they have interfered with the accomplishment of the purposes implicit in the statutory scheme and to what extent the other side can justifiably claim prejudice. After such an assessment, the judge is to decide whether the appeal should go forward without more, or on terms, or fail altogether.

369 Mass. at 79-80. As noted in Konover, [t]his is entirely in keeping with the modern judicial attitude toward procedural issues, which favors decisions on the merits, disfavors decisions on the basis of mere technicalities, and seeks to assist, not hinder, persons who have cognizable legal claims to bring their problems before the courts. Konover, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 323, n. 8.

In the circumstances of this case, I find and rule that the plaintiffs failure to attach the boards decision to their originally filed and served notices and complaint does not mandate the dismissal of their appeal. The central purpose of G.L. c. 40A, § 17s notice provisions is to ensure that the board, the variance holder, and interested third persons be forewarned that the zoning status of the land is still in question and have the opportunity to review [the] details of the challenge. Konover, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 325, 326. This was achieved by the documents that were filed and served. As noted above, both the complaint and the notices were timely filed in the proper places, timely served to the proper parties, and correctly referenced the parties names and addresses, the property at issue, the variance (by date), the court and docket number where the appeal had been filed, and the grounds of the appeal. No one has shown any confusion or prejudice of any kind. See Konover, 32 Mass. App. Ct. at 327; Twomey v. Bd. of Appeals of Medford, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 770 , 773-774 (1979). [Note 2]

I thus turn to the second question: the merits of the variance. Were the requirements of such a grant satisfied?

The Lot Shape provision that triggered the need for a variance is as follows:

The lot shall be large enough to contain a rectangle having one side equal in length to the required frontage and situated parallel to the mean direction of the front lot line and the other side equal to three-fourths (3/4) of the required frontage. Where the front lot line is curved, the mean direction of the front lot line shall be the line established by connecting the intersection points of the side property lines with the street line. Said rectangle shall touch the front lot line, but no part of said rectangle shall intersect any lot line.

Ordinance, §200-42.B. The purpose of such a requirement assuring that the front part of the lot, to a significant depth, is at least as wide as the required frontage is to regulate density, promote uniformity, prevent crowding along streetfronts and, by avoiding narrow throats in the front section of the lot, assure emergency police, fire and ambulance access. See, e.g., Schiffone v Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Walpole, 28 Mass. App. Ct. 981 , 984 (1990).

The Beane lots are in an A-3 District, requiring a minimum of 100 feet of frontage. Ordinance, §200-41. The lot shape provision thus requires that those lots, to be buildable, be at least 100 feet wide at every point from their frontage on the street to 75 feet back. Lot #2 clearly fails this test, and badly. It is 100 feet wide at the street, drops almost immediately to less than 80 feet, and does not become 100 feet or wider until over 80 feet back on the lot. See Ex. 1. As the Beanes recognized, it needs a variance for a home to be built upon it.

Variances are governed by G.L. c. 40A, § 10 which states, in pertinent part:

The permit granting authority shall have the power... to grant upon appeal or upon petition with respect to particular land or structures a variance from the terms of the applicable zoning ordinance or by-law where such permit granting authority specifically finds [1] that owing to circumstances relating to the soil conditions, shape, or topography of such land or structures and [2] especially affecting such land or structures but not affecting generally the zoning district in which it is located, [3] a literal enforcement of the provisions of the ordinance or by-law would involve substantial hardship, financial or otherwise, to the petitioner or appellant, and [4] that desirable relief may be granted without substantial detriment to the public good and [5] without nullifying or substantially derogating from the intent or purpose of such ordinance or by-law.

The Supreme Judicial Court has repeatedly held that no variance can be granted unless all of the requirements of this statute are met. Warren v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Amherst, 383 Mass. 1 , 9-10 (1981) (emphasis added). Since the requirements for the grant of a variance are conjunctive, not disjunctive, a failure to establish any one of them is fatal. Kirkwood v. Bd. of Appeals of Rockwood, 17 Mass. App. Ct. 423 , 428 (1984) (citing Blackman v. Bd. of Appeals of Barnstable, 334 Mass. 446 , 450 (1956)). Moreover, variances are to be granted sparingly. Id. (citing Damaskos v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 359 Mass. 55 , 61 (1971)); Dion v. Bd. of Appeals of Waltham, 344 Mass. 547 , 555 (1962).

When a variance is challenged in court, the burden is upon the person seeking a variance, and the board granting one, to produce evidence that each of the discrete statutory prerequisites has been met and that the variance is justified. Kirkwood, 17 Mass. App. Ct. at 427. Then:

[u]pon appeal, it is the duty of the judge to hear all the evidence and to find the facts. He is not restricted to the evidence that was introduced before the board. The decision of the board is competent evidence to enable the judge to ascertain what conclusion the board reached in order that he may determine whether upon the facts found by him the decision of the board should stand or be annulled or should be modified. In a word, the matter is heard de novo and the judge makes his own findings of fact, independent of any findings of the board, and determines the legal validity of the decision of the board upon the facts found by the court, or if the decision of the board is invalid in whole or in part, the court determines what decision the law requires upon the facts found.

Bicknell Realty Co. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 330 Mass. 676 , 679 (1953). See also Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys. Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 485-486 (1999) (citing Bicknell and other cases).

The board granted the Beanes a variance, but its factual findings in support of that grant are odd and seem directly contrary to the result reached. They were not supported by the evidence at trial.

If I understand its decision correctly, the board found that Lot #2 had no unusual soil or topographical conditions (I agree; none were shown at trial) and met the shape requirement only because of the strange shape of the proposed lot, created through an ANR plan. Decision of the Board of Appeals Granting a Variance, Case No. 1375-2008 at 1 (Dec. 5, 2008). But that ANR plan (Ex. 1), and whatever strangeness it reflects, was the Beanes own creation the way they chose to divide their pre-existing, fully compliant house lot, in full knowledge that the lot so created violated the shape requirement. See Ex. 1. [Note 3] A variance is not warranted in these circumstances. See Feldman v. Bd. of Appeals of Boston, 29 Mass. App. Ct. 296 , 297-298 (1990) ([A] lot cannot qualify for a variance based on subminimum dimensions when the undersized lots were created by transfer of land from a once conforming lot.) (citing cases).

The hardship the board found was the expense to Mr. Beane if he [had] to move his existing house in order for the proposed lot to meet the lot shape requirement. Id. But such a self-created financial hardship does not justify a variance. See Kirkwood, 17 Mass. App. Ct. at 431 (deprivation of potential economic advantage to landowner does not qualify as substantial hardship). Moreover, the underlying assumption is incorrect. Moving the house solves nothing. It is not physically possible to divide the Beane property into two conforming lots. This is because the Beane property is not a perfect rectangle. It is 201 feet wide at streetside, so each lot could get a full 100 feet of frontage, but narrows to only 188.58 feet at the rear. At 75 feet back, the total width is less than the 200 feet needed (100 feet for each lot) for both to comply with the lot shape ordinance. See Ex. 2. The Beanes conceded this at trial.

Transcript at 155-156.

The board made the explicit finding that the variance [could] not be granted without substantial detriment to the public good because: building this house will cause an unreasonable hardship for a number of abutters and the house effectively has less than [the] 100 ft. frontage required, due to a small 24 ft. triangle by creating [the parcel] through an ANR in 2004. [Note 4] And, because of that, you would be creating a crowded condition in the westerly direction of Shawmut Ave. (westerly of the existing Beanes house). Board Decision at 1-2. This alone should have resulted in the denial of the variance. See Kirkwood, 17 Mass. App. Ct. at 428 (Since the requirements for the grant of a variance are conjunctive, not disjunctive, a failure to establish any one of them is fatal). Yet the board concluded by saying that desirable relief may be granted without substantially derogating from the intent and purpose of the zoning bylaw because: The lot in question is one of the larger lots in the area [and] meets all other requirements for Zoning District A-3 for a buildable lot, except for the lot shape requirement, and then voted 4-1 to grant the variance. Board Decision at 2-3.

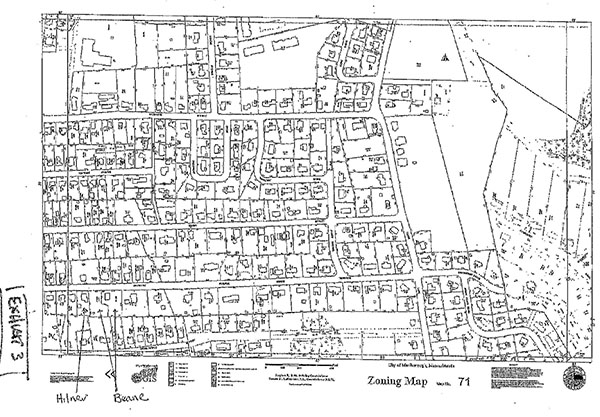

I agree with the board, and on the evidence so find, that the construction of a house on Lot #2 will increase crowding along Shawmut Avenue an already dense neighborhood. See Ex. 3. This is obvious. What had been vacant would now be occupied by a house, garage and driveway with a new curb cut, see Ex. 2, and the neighbors most affected are those to the west, including the Hilners. See Ex. 3. I also agree with the board, and on the evidence so find, that approving a variance for a lot shaped this way would cause substantial detriment to the public good, particularly to the west. This is because, as the board noted, twenty four feet of the one hundred foot frontage is effectively illusory, resulting in the house being located further to the west than it otherwise would, and thus more crowding in that direction than would ordinarily occur. [Note 5] I need not address the boards final finding that desirable relief may be granted without substantially derogating from the intent and purpose of the zoning bylaw because the variance fails all the other criteria, and compliance with each is required for a variance to be valid. Kirkwood, 17 Mass. App. Ct. at 428; Guiragossian v. Bd. of Appeals of Watertown, 21 Mass. App. Ct. 111 , 115 (1985). I have great sympathy with the Beanes desire to provide a home to their son and his family, but the grant of a variance [must] be based only upon circumstances which directly affect the real estate and not upon circumstances which cause personal hardship to the owner. The criteria in the act relate to the land, not to the applicant. Huntington v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Hadley, 12 Mass. App. Ct. 710 , 715 (1981) (internal quotations and citations omitted). The special circumstances justifying the grant of a variance must relate to the soil conditions, shape or topography of such land or structures. Id. (internal quotations and citations omitted). Here, they do not.

The analysis thus turns to the third issue: do the Hilners have standing to challenge the Beanes variance? This was the focus of the trial.

The test for standing, and the standards by which it is judged, are the familiar ones. Only a person aggrieved may challenge a decision of a zoning board of appeals. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); G.L. c. 40A, §17. Individual

property owners acquire standing by asserting a plausible claim of a definite violation of a private right, a private property interest, or a private legal interest. Harvard Square Defense Fund Inc. v. Planning Bd. of Cambridge, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 491 , 492-93 (1989). The right or interest asserted by a plaintiff claiming aggrievement must be one that the Zoning Act is intended to protect, either explicitly or implicitly. 81 Spooner Road LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012). To assert a plausible claim of injury to such an interest, a plaintiff must put forth credible evidence to substantiate his allegations. Marashlian, 421 Mass. at 721. Credible evidence has

both a quantitative and a qualitative component....Quantitatively, the evidence must provide specific factual support for each of the claims of particularized injury the plaintiff has made. Qualitatively, the evidence must be of a type on which a reasonable person could rely to conclude that the claimed injury likely will flow from the boards action. Conjecture, personal opinion, and hypothesis are therefore insufficient.

Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 441 (2005).

Abutters such as the Hilners have a rebuttable presumption of aggrievement. 81 Spooner Road LLC, 461 Mass. at 700. That presumption can be rebutted in two ways. First, a defendant may show that the rights allegedly aggrieved are not interests protected by G.L. c. 40A, §17 or the local zoning ordinance. This rebuts standing because [a]n abutter can have no reasonable expectation of proving a legally cognizable injury where the Zoning Act and related zoning ordinances or bylaws do not offer protection from the alleged harm in the first instance. Id. at 702; Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 35 (2006). Second, where a plaintiff has alleged harm to an interest protected by G.L. c. 40A, the defendant can rebut the presumption by producing credible evidence to refute the presumed fact of aggrievement. This can be done by testimony showing the aggrievement either unfounded or de minimus. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 35-36. Once rebutted, the burden shifts back to the plaintiff to establish by direct facts and not by speculative personal opinion that his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community. Id. at 33.

The Hilners claim aggrievement based on their contention that the residence allowed by the variance will increase density and congestion in the neighborhood, with particular effect on their house next door. Specifically, they claim it will lower the fair market value of their house an objective measure of the price a willing buyer would pay for the property in an arms-length transaction, taking into account all factors that such a buyer reasonably would consider, value, and rely upon. Showing such aggrievement has three components.

First, density and congestion must be interests protected by the ordinance. They are. See Ordinance, §200.02 (identifying to secure safety from fire, confusion or congestion and to avoid undue concentrations of population as among the purposes of the ordinance). See also the purposes of the lot shape provision, discussed supra.

Second, the Hilners must show that the increased density and congestion produced by the variance affect the neighborhood as a whole. They have done so by showing that the neighborhood is already far more dense than current zoning allows. See Dwyer v. Gallo, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 292 , 295-296 (2008) (The agreed facts reveal that the [parties properties] are located in a neighborhood where construction is already more dense than allowed by the current zoning. We have recognized an abutters legal interest in preventing further construction in a district in which the existing development is already more dense than the applicable zoning regulations allow.) (internal citations and quotations omitted); Sheppard v. Zoning Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 8 , 11-12 (2009) (An abutter has a well-recognized legal interest in preventing further construction in a district in which the existing development is already more dense than the applicable zoning regulations allow. As the trial judge observed, [the plaintiffs] neighborhood was already dense and overcrowded) (internal citations and quotations omitted). As the evidence showed, the neighborhood around the parties homes is such a place.

Q [of plaintiffs expert real estate appraiser, William Curley]: Now, in regard to your description of where the Hilners and the Beanes live, could you describe for the court the density or, you know, the density of that neighborhood?

A; Generally speaking, it is a fairly dense neighborhood. In fact before the zoning by-law in 1969, most of the lots were small, and they had frontages between 50 and 65 and 70 feet. [Note 6] And they all were a lot of them were anywhere from 7,000 to 10,000 square feet. [Note 7] The Hilners was 66 feet of frontage, and it had 88 84 square feet with a depth on the easterly border with Beanes of 153 feet in linear length.

Q: Is it fair to say, given what youve described as the density, that generally the lots in that neighborhood would not be conforming to the current building Marlborough building ordinance?

A: With the exception of a few. Generally speaking, theyre all substandard, but legal lots because they were built prior to the zoning ordinance.

Trial transcript at 49-50. See also Ex. 3 (attached).

Third, the Hilners must show that they are particularly affected that their injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community and do so by direct facts and not by speculative personal opinion. Standerwick, 447 Mass. at 33. They have met that burden through their presumption of standing as direct abutters a presumption not rebutted by evidence from the Beanes [Note 8] and through Mr. Curleys testimony even had that presumption been rebutted.

Mr. Curley testified that a residence on the otherwise unbuildable variance lot would decrease the market value of the Hilner home by 20%. I am not convinced that 20% is the correct figure (too high), but I am persuaded it would cause a significant drop. The new residence would be over seventy feet closer than the Beanes current home and less than 25 feet from the side and windows of the Hilners house. There will be a loss to the Hilners of privacy and light and an inevitable increase in nighttime noise and other intrusions the sights and sounds of round-the-clock human habitation. The Hilners are correct that these are different from the impacts of accessory buildings which could be built in that location without a variance. [Note 9] Accessory buildings, unlike residences, are not lived in or much used after dark.

These impacts from a new residence so close to the Hilners do not make the Hilner home unsaleable. Far from it. It remains valuable. But not as valuable. I agree with Mr. Curley that homebuyers will pay a premium for the privacy that currently exists, and measurably less if it does not. This type of injury a loss in fair market value, directly attributable to the increased density allowed (and allowable only) by the variance [Note 10] is a true and measurable harm, see Kenner v.Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 122 (2011), within the reach of the zoning laws, even if the structure so built would be compliant with sideline setback requirements. On facts such as these, our appellate courts have consistently recognized a neighbors right to contest zoning failings of projects which, given their excessive density, push themselves, in a materially intrusive adverse way, in the neighbors direction. Pettinella v. Cavallaro, 19 LCR 340 , 344 (2011) (Piper, J.) (citing Sheppard and Dwyer, supra). [Note 11] I thus find that the Hilners have standing to object to the variance. [Note 12]

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the boards decision allowing the variance is VACATED. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

GARY HILNER and CONNIE HILNER v. LARRY BEANE, SANDRA BEANE, and JAMES NATALE, JOHN SAHAGIAN, WILLIAM KING, PAUL GIUNTA and LYNN FAUST as members of the Marlborough Zoning Board of Appeals.

GARY HILNER and CONNIE HILNER v. LARRY BEANE, SANDRA BEANE, and JAMES NATALE, JOHN SAHAGIAN, WILLIAM KING, PAUL GIUNTA and LYNN FAUST as members of the Marlborough Zoning Board of Appeals.