This case is brought by HSBC Bank, assignee of a mortgage granted by Defendants Sundar and Rena Gongaju, to establish title by adverse possession in the Gongajus of a portion of property located at 28 Blaine Street, Boston (Mortgaged Premises). The suit names as Defendants the mortgagors as well as Elena Nefedova, whose property abuts the Mortgaged Premises and who is the owner of record of the area in dispute. [Note 2] HSBC Bank seeks to conform the boundary line of the Mortgaged Premises to existing fence lines outlining Parcel A on Exhibit H to the Amended Complaint. [Note 3] Plaintiff also seeks to reform the mortgage it holds to include all of Parcel A and also asks the court to enter judgment confirming that neither of the Gongajus are entitled to benefits under the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act. Resolving this boundary line issue would allow HSBC Bank to request a lift of a stay imposed by a judge of the Superior Court Department in a related action (currently pending until this action is concluded), so that HSBC Bank may proceed with foreclosure of its mortgage, currently in default.

Defendants Sundar K. Gongaju and Rena Gongaju filed an Answer and Crossclaim on March 25, 2010, asserting several affirmative defenses. [Note 4] They filed a crossclaim against Nefedova for adverse possession of Parcel A, adopting the arguments of HSBC Bank for purposes of that crossclaim, oddly leaving HSBC Bank and the Gongajus, otherwise adversaries, on the same side of the sole issue tried before this court. Defendant Nefedova filed an Answer and Crossclaim on April 16, 2010, denying both HSBC Banks and the Gongajus claims of adverse possession and asserting affirmative defenses to both the Complaint and Crossclaim. [Note 5] Nefedovas Crossclaim against the Gongajus sought a permanent injunction restraining them from using the disputed area, denying their claim of adverse possession, and confirming the metes and bounds of her own lot. [Note 6]

A one-day trial was held on December 13, 2011. The court heard testimony from Defendants Sundar and Rena Gongaju; Defendant Elena Nefedova; Stephen E. Stapinski, an expert registered land surveyor; Arlene Plachowicz and Irene Fitzgibbon, both former residents of 28 Blaine Street; and Michael Amaru, a real estate agent and developer. Fifteen exhibits were entered in evidence. At the conclusion of HSBC Banks case-in-chief, the Gongajus, Elena Nefedova, and Wells Fargo each moved for a directed finding, which this court denied. All parties filed post-trial briefs in February, 2012.

Based on the credible testimony, record exhibits and other evidence entered at trial, the facts previously established by the parties in their Joint Pre-Trial Memorandum and the reasonable inferences drawn therefrom, this court finds the following facts:

1. The deeds for 28 Blaine Street and 30 Blaine Street (collectively Subject Properties) refer to a plan made by E.S. Smith Surveyor, dated November 1889, recorded with the Suffolk Registry of Deeds in Book 1915, at Page 481 (1889 Plan). [Note 7] The 1889 Plan shows land only and does not depict any structures thereon. The Subject Properties were originally part of a development known as Hanoville named for Samuel Hano, owner of a factory in the area.

28 Blaine Street (Lot 30)

2. Sundar K. Gongaju and Rena Gongaju are the present owners of Lot 30 on the 1889 Plan, together with the building thereon, known and numbered as 28 Blaine Street, Boston (28 Blaine Street). The Gongajus have maintained the home located thereon as their principal residence since 2003.

3. On or about May 23, 2003, Sundar K. Gongaju executed a promissory note in the amount $267,750.00 to Fieldstone Mortgage Company (Fieldstone), and Sundar K. Gongaju and Rena Gongaju executed a mortgage of 28 Blaine Street to Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc. (MERS), as nominee for Fieldstone. The Mortgage is recorded in Book 31535, at Page 91.

4. HSBC Bank (USA) n/k/a HSBC Bank USA, N.A., is the record assignee of the mortgage on 28 Blaine Street. The assignment is recorded in Book 45286, at Page 175.

5. The mortgage given to HSBC Banks predecessor-in-interest describes 28 Blaine Street as Lot 30 on the 1889 Plan and includes the following metes and bounds description:

Northwesterly by Blaine Avenue, thirty (30) feet;

Northeasterly by Lot 29, on said plan, forty-four and 8/100 (44.08) feet;

Southeasterly by land now or late of Arnold A. Rand et al., Trustees, thirty (30) feet;

Southwesterly by Lot 31 on said plan, thirty-nine and 93/100 (39.93) feet.

6. The title evidence at trial started the Gongaju chain of title in 1909, with a plot plan indicating that 28 Blaine Street and 30 Blaine Street were originally owed by William Lincoln.

7. Arlene Plachowicz resided with her parents at 28 Blaine Street from 1945 when she was born until 1972, although she never owned the property.

8. 28 Blaine Street was owned by Edward Bryne from 1984 to 1999. Mr. Byrnes family owned 28 Blaine Street as far back as 1965. Edward Bryne conveyed the property to Paul S. Fitzgibbon by deed dated November 24, 1999, recorded in Book 24444, at Page 273, who deeded to himself and Irene Fitzgibbon on March 20, 2000, by deed recorded in Book 24820, at Page 165.

9. On or about May 23, 2003, Paul S. Fitzgibbon and Irene Fitzgibbon conveyed their interest in 28 Blaine Street to Sundar K. Gongaju by deed recorded in Book 31535, at Page 85.

30 Blaine Street (Lot 31)

10. Elena Nefedova is the present owner of Lot 31 on the 1889 Plan, together with the buildings thereon known and numbered 30 Blaine Street, Boston (30 Blaine Street).

11. She originally purchased 30 Blaine Street with her mother on March 8, 2001, and has owned it herself since April 21, 2005.

12. The mortgage given by Nefedova to Washington Mutual F.A., describes 30 Blaine Street as Lot 31 on the 1889 Plan and includes the following metes and bounds description:

Northwesterly by Blaine Street, formerly Blaine Avenue, thirty (30) feet;

Northeasterly by Lot Thirty, on said plan, 39.93 feet more or less;

Southeasterly by land of owners unknown, 30.28 feet more or less, and;

Southwesterly by lot Thirty-Three on said plan, 35.78 feet more or less.

13. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., as Trustee for Freddie Mac Securities REMIC Trust 2005-S001 (Wells Fargo) is a federally registered National Association and is the current mortgagee of record of the first mortgage of 30 Blaine Street.

28 Blaine Street (Lot 30)

14. HSBC Bank initiated foreclosure proceedings on the Gongaju property and on November 7, 2006, HSBC Bank filed a Complaint to determine the Gongajus military status in the Land Court, pursuant to the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act.

15. The Land Court entered Judgment on February 7, 2007, determining that the Gongajus are not entitled to the benefit of the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act. As of the date of trial, neither Sundar nor Rena Gongaju was in the military.

16. On December 17, 2007, the Gongajus commenced an action in Suffolk Superior Court against numerous defendants, including HSBC Bank, and sought injunctive relief against HSBC Bank to stop the foreclosure, to give the Gongajus time to sell the property, thus avoiding foreclosure. In their Superior Court complaint, the Gongajus alleged that they could not complete a sale of 28 Blaine Street prior to the foreclosure due to title issues concerning the propertys boundary lines, here in issue.

17. HSBC Bank filed a Motion for Summary Judgment in the Superior Court case and, on March 11, 2011, the court granted HSBCs Motion for Summary Judgment as to all issues except for the boundary issue, now before this court.

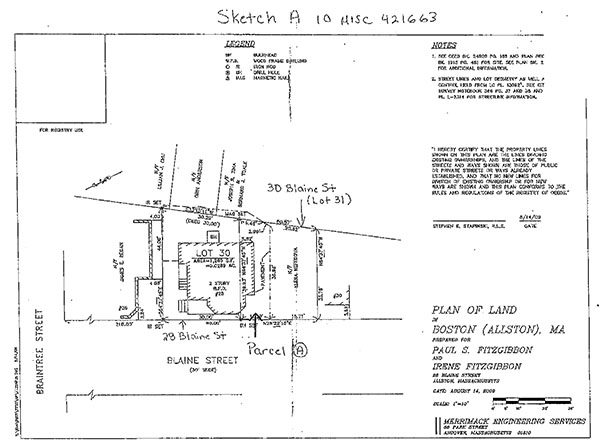

18. The court finds that the Subject Properties are located as shown on Exhibit H to the Complaint (from which Sketch A, attached to this decision, is derived). As shown on Sketch A, the disputed area runs 11.29 feet southerly from the boundary line between Lot 30 and Lot 31. At its farthest point, the house on 30 Blaine Street encroaches onto 31 Blaine Street by 5.52 feet. The house at 28 Blaine Street was constructed in 1916, and has remained in its location since that date.

19. A chain link fence separates the Gongaju and Nefedova properties. A chain link fence also runs along the sidewalk and extends from the corner of the house on 28 Blaine Street to the front entrance of 30 Blaine Street.

20. Some type of fence has existed approximately in the location of the existing chain link fence between the properties since 1945, but its origin is unknown.

* * * * * *

The parties do not dispute that a small portion of the Gongajus house is located over the boundary line along the Nefedova property. At trial, the sole issue was whether the disputed area, which includes the land under the house, has been used by the Gongajus and their predecessors-in-title in such a way as to perfect title by adverse possession of the disputed area. [Note 8]

HSBC Bank commissioned a survey in August 2009, which confirmed that improvements on 28 Blaine Street encroached on 30 Blaine Street by 11.29 feet. The Gongaju house encroaches 5.52 feet onto 30 Blaine Street. As shown on Sketch A, the portion of disputed area that is closest to Blaine Street is paved. A chain link fence separates the two properties and delineates the limit of the disputed area. In their Superior Court case, the Gongajus alleged that HSBC Bank lacked standing to foreclose and that the assignment from Fieldstone to HSBC Bank was invalid. The Superior Court (Brassard, J.), addressed these claims at summary judgment, and ruled that HSBC Bank had standing as a holder in due course. The court did not address the encroachment that the Gongajus alleged prevented their scheduled sale. [Note 9] At a pretrial conference for the Land Court case on September 13, 2011, this court expressly stated that it would not revisit the Superior Courts ruling regarding HSBC Bank and narrowed the issue for trial to the factual and legal questions of whether the existing encroachment rises to the level of adverse possession.

A party claiming title to land through adverse possession must establish actual, open, exclusive and nonpermissive use for a continuous period of twenty years. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145 (2000); Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 262 (1964); see also G. L. c. 260, § 21. The guiding principle behind these elements is not to ascertain the intent or state of mind of the adverse claimant, but to provide notice to the true owner, allowing for the legal vindication of property rights. See Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 623-24 (1992); Ottavia v. Savarese, 338 Mass. 330 , 333 (1959). The element of nonpermissiveness has been referred to interchangeably in case law as "hostile," "adverse," or "under a claim of right." Totman, 431 Mass. at 145. The essence of nonpermissive use is lack of consent from the true owner. Ottavia, 338 Mass. at 333-34.

If the claimant has not used the claimed property for the required twenty-year period, he or she can tack on a grantors period of use in order to satisfy the requirement, provided there is privity of estate between the adverse possessors. Kershaw v. Zecchini. 342 Mass. 318 , 320 (1961). Typically, permanent improvements or significant changes to the land must be made by the party claiming possession, but less significant activities may suffice if combined with others which together show control and dominion. Peck v. Bigelow, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 551 , 556-57 (1993). Acts of possession must constitute more than just the few, intermittent and equivocal. Kendall, 413 Mass. at 624 (quoting Parker v. Parker, 83 Mass. 245 , 247 (1861)). The party asserting adverse possession carries the burden of proof for all necessary elements, and, if any of these elements remains in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Lawrence v. Town of Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003). An owner cannot be barred of his right except upon clear proof. Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74 , 76 (1912) (citing Cook v. Babcock, 65 Mass. 206 , 210 (1853)).

Plaintiffs [Note 10] rely in large part on the existence of the chain link fence separating the two properties to satisfy the elements of adverse possession. The fence bounds the disputed area, which consists of the land on which the structure is located as well as the side yard. Arlene Plachowicz testified that she lived her whole life at 28 Blaine Street, from her birth in 1945, until she married and moved in 1972. According to Ms. Plachowicz, the fence was always there, originally as a wood fence and later replaced with the chain link fence, keeping its same dimensions. Irene Fitzgibbon also testified regarding her personal recollections of the fence. Her first memory of 28 Blaine Street took place approximately around 1965, when she visited the then-owner, Eddie, a family friend and from whom she later bought the property. [Note 11] The chain link fence was in place at that time.

Based on the evidence, the court finds that Plaintiffs established that a fence has been in existence substantially in its present location since approximately 1945, a period well in excess of twenty years. However, neither Plaintiffs nor any other party determined at trial ownership of the fence, the date of its installation (of either the original wood fence or the replacement chain link fence) or who installed it. [Note 12] [W]here ownership and installation of [a wall or fence] is unknown or in dispute and where there is no evidence of it being maintained by either party to the suit, the existence of a barrier, taken alone, will not constitute an open and notorious taking of property sufficient to establish adverse possession . . . . Marciano v. Peralta, 15 LCR 267 , 270 (2007) (italics added), affd 72 Mass. App. Ct. 1117 (2008) (unpublished opinion pursuant to Appeals Court Rule 1:28). The mere existence of a barrier does not indicate whether or not its installation was permissive and is not solely determinative of adverse possession. But, taken together with maintenance activities, the construction and maintenance of a barrier in a disputed area by the adverse claimant or his predecessor-in-title may be sufficiently open and notorious to establish adverse possession. Greally v. Morello, Jr., 19 LCR 127 , 130 (2011). Plaintiffs allege such maintenance activities occurred in the instant case. Therefore, the question becomes whether the Gongajus and their predecessors used the disputed area continuously throughout the required twenty years and conducted sufficient maintenance activities or other uses, in satisfaction of the remaining adverse possession elements. The court finds that they did not.

When evaluating actual and open use, the court examines the nature of the occupancy in relation to the character of the land. Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556 (quoting Kendall, 413 Mass. at 624). The use of or changes to the disputed area must exhibit a control and dominion so as to be readily considered acts similar to those ordinarily associated with ownership[.] Peck, 34 Mass. App. Ct. at 556 (citing LaChance v. First Natl Bank & Trust Co., 301 Mass. 488 , 491 (1938)). An adverse claimant must demonstrate such open and notorious uses of the disputed area so as to put the true owner on notice of the claimants non-permissive use. Ottavia, 338 Mass. at 333-334.

Arlene Plachowicz, Irene Fitzgibbon and Sundar and Rena Gongaju all testified regarding the use of the disputed area. Ms. Plachowicz testified that, as a child, she never really played in the area, as there were bushes obstructing it. Ms. Fitzgibbon described a specific memory of roller-skating on the disputed area, but did not provide further detail or mention any other playtime activities that demonstrated a continuous use of the area. Rena Gongaju testified that her daughter generally plays in the backyard or stays within Ms. Gongajus view (which is the backyard or from the front door of the house, and not in the disputed area). In total, little testimony was offered by Plaintiffs regarding the use of the disputed area for playing or other activities, and the testimony offered was vague and lacking specific detail, and spoke to only occasional, intermittent use.

The evidence regarding maintenance of the disputed area was equally sparse. Ms. Plachowicz provided no testimony regarding the bushes obstructing the fence, particularly whether her family planted them or maintained them. Ms. Plachowicz testified that her brother paved over the grass and created the black top in the early 90s or maybe [the] late 80s, but had no knowledge of whether pavement was laid on both sides of the fence at that time. This was a one-time event, with no evidence presented of other instances of paving or patching. Sundar Gongaju testified that, in terms of maintenance, he has only cleared out some grass that might grow in the black top, but neither he nor his wife planted anything or used the area for social gatherings, or other activities. Ms. Nefedova testified that she rarely observed the disputed area being used by the Gongajus. She offered evidence of her own use of the fence, testifying that she wove ivy back and forth between the fence for the past ten years. No party provided testimony or other evidence that the disputed area was ever used for parking, and the disputed area is not needed for parking.

The absence of proof that the adverse claimant or a predecessor-in-title installed the original fence or barrier is not a complete bar to an adverse possession claim. See Brandao v. DoCanto, 80 Mass. App. Ct. 151 , 158 (2011). However, the simple existence of a fence, without more, is not enough to establish adverse possession. Here, Plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of proof for all elements of their adverse possession claim. They did not provide sufficient evidence regarding the actual and continuous use of the disputed area and could offer only sporadic instances of maintenance and use by the Gongajus and their predecessors-in-title. Because they did not establish each required element with clear proof, Tinker, 213 Mass. at 76, Plaintiffs cannot prevail on their adverse possession claim for the entirety of the disputed area.

The House

The house at 28 Blaine Street encroaches 5.52 feet onto 30 Blaine Street. The house was constructed in 1916. Evidence presented at trial demonstrated that it has been used as a residence since at least 1945, the year Ms. Plachowicz was born and began living in the house. It has continued to be used as a residence since that time by subsequent owners, such as the Fitzgibbons and the Gongajus. Ms. Plachowicz testified that the portion of the house that jogs out into the paved area has always been there. Ms. Fitzgibbon confirmed this during her testimony, stating that the part of the house that juts out has always looked like that.

Although never expressly stated or elicited during her testimony, Ms. Nefedova was clearly aware of the neighboring house at 28 Blaine Street and, despite rarely seeing them use the paved portion of the disputed area, she observed the Gongajus living in and occupying the house. The existence of the house, with the Gongajus and their predecessors living in it for the requisite period of years, is sufficient to establish adverse possession. Therefore, while Plaintiffs were not successful in proving the actual and continuous use required for adverse possession of the entirety of Parcel A, they have sufficiently proven all of the required elements for adverse possession of the land on which the Gongaju house sits, as shown on Sketch A. Therefore, Plaintiffs claim of adverse possession of Parcel A is ALLOWED in part and DENIED in part.

HSBC Bank has until February 7, 2014, to submit a plan consistent with this decision, showing the boundaries of the portion of Parcel A that this court has found is owned by the Gongajus by adverse possession. The court will issue a judgment upon receipt of the plan, to be recorded along with the Judgment.

HSBC BANK (USA), f/k/a HSBC BANK USA, N.A., [Note 1] v. ELENA NEFEDOVA, SUNDAR K. GONGAJU, RENA GONGAJU a/k/a REENA GONGAJU, MOUNTAIN PEAKS FINANCIAL SERVICES, INC., MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC., and WELLS FARGO BANK, N.A., as TRUSTEE for FREDDIE MAC SECURITIES REMIC TRUST 2005-S001.

HSBC BANK (USA), f/k/a HSBC BANK USA, N.A., [Note 1] v. ELENA NEFEDOVA, SUNDAR K. GONGAJU, RENA GONGAJU a/k/a REENA GONGAJU, MOUNTAIN PEAKS FINANCIAL SERVICES, INC., MORTGAGE ELECTRONIC REGISTRATION SYSTEMS, INC., and WELLS FARGO BANK, N.A., as TRUSTEE for FREDDIE MAC SECURITIES REMIC TRUST 2005-S001.