Introduction

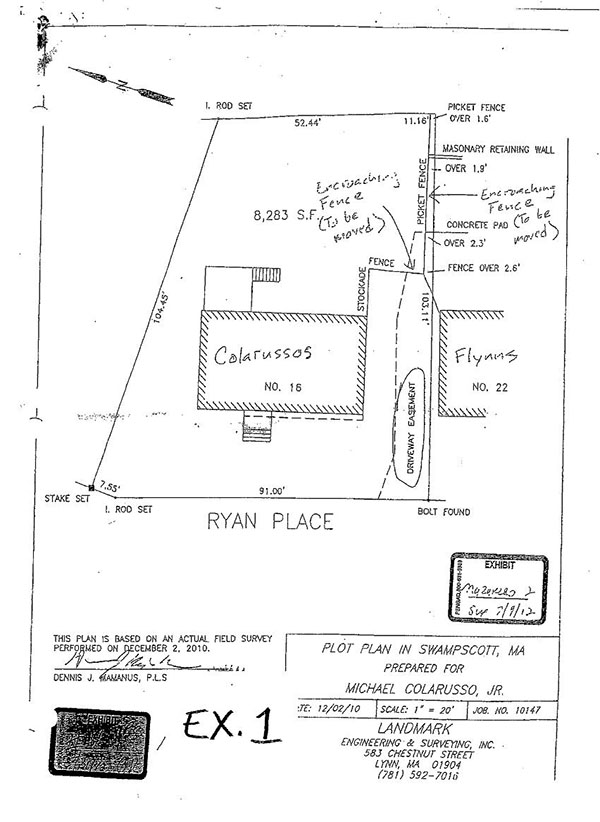

This case is a dispute over the scope of an express driveway easement located between abutting residential properties in Swampscott. The easement burdens property owned by the defendants, the Colarussos, who reside at 16 Ryan Place, and benefits the plaintiffs, the Flynns, who live next door at 22 Ryan Place. See 2010 Plot Plan for Michael Colarusso Jr., attached as Ex. 1. At trial, the Colarussos stipulated that the Flynns have the right to pass over the easement by vehicle and by foot to access the rear of their property. The central dispute between the parties is whether the easement is limited to that purpose, or whether the Flynns also have the right to park their vehicles in the easement area. The Flynns contend that such a right is conferred by the language of the grant and the circumstances surrounding its creation. The Colarussos disagree.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find the scope of the easement is limited solely to the right of passage by vehicle and by foot for access to the rear of the Flynns property, with no right to park within the easement area. As its servient owners, the Colarussos have the right to use the property burdened by the easement for any and all purposes not inconsistent with the Flynns right of access.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

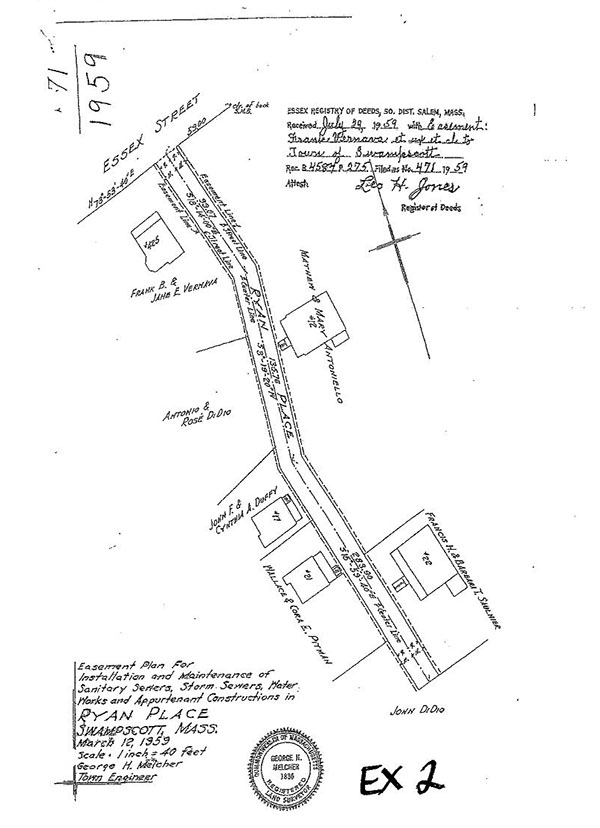

Before what is now the Colarussos lot was created by subdivision, it was part of 12 Ryan Place, a large lot owned by Matthew and Mary Antoniello. [Note 1] See Ex. 2 attached (Plan of Ryan Place 1959). Matthew Antoniello Jr., the son of Matthew and Mary, lived at 12 Ryan Place from the time he was born in 1947 until he sold the property and moved away in approximately 1984. [Note 2] When Mr. Antoniello was growing up, 22 Ryan Place (now owned by the Flynns) was owned by Francis and Barbara Saulnier who had a driveway to the left of their house leading to a garage in their back yard. [Note 3] Mr. Saulnier was a carpenter and used the driveway to get to and from the garage where he stored tools, lumber and bicycles. He would also occasionally leave a vehicle in the driveway as did his sons after they reached driving age and acquired their own cars.

At some point, when Mr. Antoniello was still a child, Mr. Saulnier had the driveway hot topped. Mr. Antoniello recalled roller skating on the driveway with Mr. Saulniers sons, a further indication that parking there was infrequent. The Saulniers eventually sold 22 Ryan Place to the Coombes family who used the driveway much the same way.

In 1976, Mr. Antoniello became the owner of 12 Ryan Place, taking title from his three sisters. He lived there with his wife and, in 1983, subdivided the property into two separate lots, No. 12 and No. 16 Ryan Place. In the mid 1980s, he sold 12 Ryan Place to the town of Swampscott. Then, within a year after moving from the neighborhood, he sold 16 Ryan Place, which was vacant land at the time, to Patrick McManus, James Mazareas, and Thomas Costin, Jr. as tenants in common (hereafter McManus Group) in 1986 who bought it as an investment and planned to build and sell a residence on it.

In late 1986, the McManus Group obtained a foundation permit from the Swampscott building inspector for the residential structure they planned. Shortly after the foundation work began, the Coombeses, then owners of 22 Ryan Place, brought suit alleging the foundation encroached on the driveway, which they contended was on their property. As a record matter (the record boundary) it was not, so the Coombeses based their arguments on alleged adverse possession or prescriptive rights.

The McManus Group strongly disagreed with both aspects of this assertion, and Mr. Mazareas felt the case should be litigated to conclusion. Mr. Costin and Mr. McManus, however, did not want their development plans held up by years of litigation and instead preferred to grant the Coombeses an easement as a way of settling the dispute. Mr. Mazareas and Mr. Costin both testified about that lawsuit and its resolution. Mr. McManus had died, and thus did not. Neither the Coombeses nor their attorneys were called as witnesses.

Mr. Mazareas did not participate in the negotiation or drafting of the easement. As he recalled, Mr. McManus, who was an attorney, presented the grant of easement for his signature. Mr. Mazareas could not recall whether or not he read the easement before he signed it, stating I sign a lot of things I dont read, but he did not believe it included a right to park. He certainly never intended such a grant. As he explained, by granting someone the ability to park on that [the easement], you would greatly diminish the value of what we were proposing to build.

Mr. Costin likewise was not involved in the direct negotiations but, like Mr. Mazareas, understood that the easement was only for the purpose of ingress and egress to and from 22 Ryan Place and not for parking. Like Mr. Mazareas, and for the same reasons, he did not intend to grant a right to park. No evidence was introduced at trial of what Mr. McManus said to the Coombeses or they (or their lawyers) to him. I thus find that the wording of the easement reflects their common understanding and all important parts of their agreement.

The easement was granted on January 26, 1993 and recorded in the Essex (South) Registry of Deeds at Book 11930, Page 162. It conveys an easement for driveway purposes giving the grantees, the Coombeses, the right to use the easement for all purposes for which public ways are used in the Town of Swampscott, to Lot 11 [22 Ryan Place] as is shown on said plan and is to be held by the Grantees, their heirs and assigns

. [Note 4] There is no mention of a right to park anywhere in the text of the instrument. The signature of a notary public on the face of the instrument attests that Mr. McManus, Mr. Mazareas, and Mr. Costin were all present at the time of the grant. Soon after the easement was granted, the Coombeses lawsuit was dismissed by stipulation of the parties, with prejudice, on February 17, 1993. The McManus Group did not have the financial resources to finish building the house at No. 16 and instead conveyed it to their lender, Century Bank and Trust, by deed in lieu of foreclosure on October 27, 1993. The house at 16 Ryan Place was subsequently constructed in 1995.

The Flynns acquired 22 Ryan Place by deed from Sharon McLaughlin (formerly DiRusso) and Anthony DiRusso [Note 5] on April 29, 2004. They were interested in the property because it was a two family and would provide rental income. [Note 6] Mr. Flynn testified that Mr. DiRusso showed him the house and, when he asked him about parking for the property, Mr. DiRusso pointed out the window to the driveway easement. [Note 7] After the Flynns purchased the property, their tenants used the easement area for parking. The Flynns themselves parked on the other (right) side of the house which, at the time they moved in, had space for two vehicles. They later expanded this parking area by removing a large granite boulder, thereby providing enough space for 4 to 5 vehicles to park on the right side of their house. Although they had ample parking on the right side of their house, the Flynns also took advantage of the easement area, storing a boat and occasionally using it for their own vehicles and those of their guests. According to Mr. Flynn, the then-owners of 16 Ryan Place (the Weidenroths) never objected to the Flynns parking on the easement. The house at 16 Ryan Place has its own attached two car garage on the right side of the house and additional driveway space in front of the garage that is large enough for two more vehicles to park.

Mr. Flynn testified that disagreements over parking on the easement arose shortly after the Colarussos purchased 16 Ryan Place in 2008. Ms. Colarusso looked at the property with a real estate agent in late 2007. She testified that around this time she would drive by the property twice a day, going to and from her father-in-laws salon where she was working at the time. During these trips, she testified she never saw vehicles parked in the easement area. The first time she became aware of the easements existence was at the closing for the sale of 16 Ryan Place when she was shown the grant of easement. She understood it to grant access rights only, not the right to park, and neither her prior owners nor their attorneys said anything different.

When the Colarussos moved in, they were friendly with the Flynns and would visit each others homes. This did not last, however. The Colarussos began to get upset that they were paying taxes on property that the Flynns used for parking. One particular day, one of the Flynns sons bought a broken-down Mustang which he planned to refurbish. The Flynns were attempting to push the vehicle on to the driveway easement when Ms. Colarusso got in her own vehicle and positioned it across the easement, blocking access. The Flynns contend that the Colarussos also began parking in the easement, blocking the Flynns access to the rear of 22 Ryan Place. This action followed.

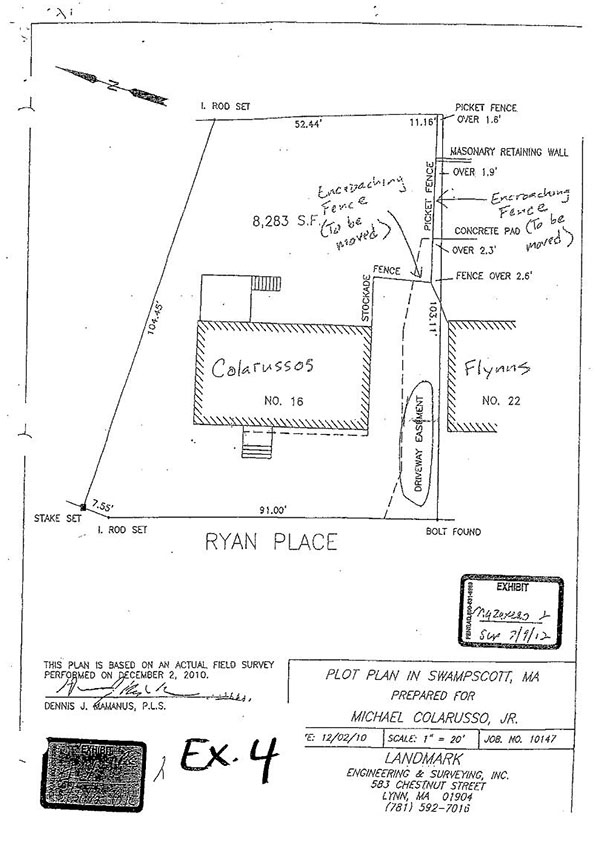

At trial, the parties reported they had narrowed the issues between them. Issues regarding the Colarussos alleged blocking of the easement were resolved by their stipulation in open court that the Flynns have the right to unobstructed use of the easement for access by vehicle and by foot to the rear of their property. At the close of trial, the parties further represented to the court that they reached agreement that the portion of the Flynns fence that encroaches on to the Colarussos property would be moved consistent with the record boundary shown on a survey plan that the Colarussos had prepared. The Colarussos also agreed to remove the portion of their stockade fence that encroaches into the easement area. [Note 8] See Ex. 4 attached (depicting sections of fence the parties agreed to move).

The only contested issues remaining are whether the Flynns easement rights include the right to park and, with respect to the Colarussos, the extent of their rights to use the portion of their property that is burdened by the easement.

Additional facts are discussed in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

In resolving disputes concerning the extent of express easement rights, the court look[s] to the intention of the parties regarding the creation of the easement or right of way, determined from the language of the instruments when read in light of the circumstances attending their execution, the physical condition of the premises, and the knowledge the parties had or which they are chargeable to determine the existence and attributes of a right of way. Doubts as to the extent of a restriction in an easement are resolved in favor of the freedom of land from servitude. Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC., 467 Mass. 1 (2014) (internal citations and quotations omitted). The Flynns rights are limited to the express easement. The 1993 dismissal, with prejudice, of the adverse possession / prescriptive easement lawsuit, resolved by the grant of the express easement at issue in this action, restarted any prescriptive period and twenty years has not run from that time to the date this action was filed. See Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 542 n. 8 (1996).

The testimony of Mr. Antoniello establishes that prior to the creation of the express easement at issue, the driveway that had been in existence was used for access by the Saulnier and Coombes families and, at least occasionally, for parking. The fact that such parking resulted in a lawsuit, however, suggests that any right to do so was very much disputed, and the easement grant must be read in that light.

There is no mention of a right to park anywhere in the text of the grant. Had that been the agreement, the grant could easily have said so and the absence of such language is strongly suggestive that it was never agreed. Mr. McManus, who negotiated the language of the grant on behalf of the grantors, was an attorney and surely appreciated precision in words. Recall that the easement was granted to resolve a lawsuit with the grantees represented by counsel as well. If such a right to park was intended, surely the grantees would have insisted on such an express statement. The instrument only conveys an easement for driveway purposes that may be used for all purposes for which public ways are used in the Town of Swampscott, to Lot 11 [22 Ryan Place now owned by the Flynns]. It has long been held that public ways only include a right to pass and repass and to make, at most, only temporary stops incident to travel. See Opinion of the Justices, 297 Mass. 559 , 562-64 (1937). The language of the grant, stating that it is an easement to Lot 11, (emphasis added) is further indication that the parties to the grant only intended to convey a right to access 22 Ryan Place. Though many property owners routinely park vehicles in their driveways, the law has not recognized that an express easement for driveway purposes necessarily includes the right to park. See Kostorizos v. Samia, 9 LCR 117 , 123 (2001) (easement granted for all purposes for which private driveways are now or hereafter used does not include right to park), affd 57 Mass. App. Ct. 1112 , 2003 WL 940803 (March 10, 2003) (unpublished Rule 1:28 memorandum and order).

Aside from the absence of any language granting an express right to park, the circumstances surrounding the grant also do not support the conclusion that the parties intended to convey such a right. The McManus Group had no intention of being the long term owners of 16 Ryan Place. When they bought the property as tenants in common, it was vacant land and they treated it solely as an investment property. Their goal was always to build a home on the lot and then sell it. As Mr. Mazareas testified, he was acutely aware that granting a right to park to the neighboring property owners would negatively affect the value of the home that he and his co-tenants wanted to build. Given the close physical proximity between the boundaries of the easement area and the location of the home that now exists at 16 Ryan Place, I find his concern was well-founded.

There is also no evidence that parking on the easement was a necessity for the Coombeses. The testimony showed that there was ample room for parking on the right side of their house. Indeed, when the Flynns bought the property, there were already spaces for two vehicles and with further modification, they are now able to park 4 to 5 vehicles on the right side of the house.

For the Coombeses, the value of the easement was that it ensured convenient access to the rear of their property. Prior to the creation of the easement, the driveway that existed in roughly the same location had always been used to provide such access by vehicle and by foot to the rear of 22 Ryan Place. The evidence established that there was room for parking elsewhere on the property, but there was no testimony that suggested the Coombeses could have had the same kind of convenient access to the rear of their property by a different route.

Given the close proximity between the house that was built at 16 Ryan Place and the location of the easement, the grantors of the easement would have been mindful of their own access issues. As Ms. Colarusso testified, she and her husband access the rear of their property by passing over the narrow strip between their home and the northern boundary of the easement. They do not have the same convenient access on the left side of their home because the topography of their lot slopes downward toward 12 Ryan Place. Parking on the easement is thus a significant obstruction to the rear of 16 Ryan Place, and I find the need to preserve unimpeded access to the rear of No. 16 is a further circumstance that supports the conclusion that parking for No. 22 was never intended to be part of the easement grant.

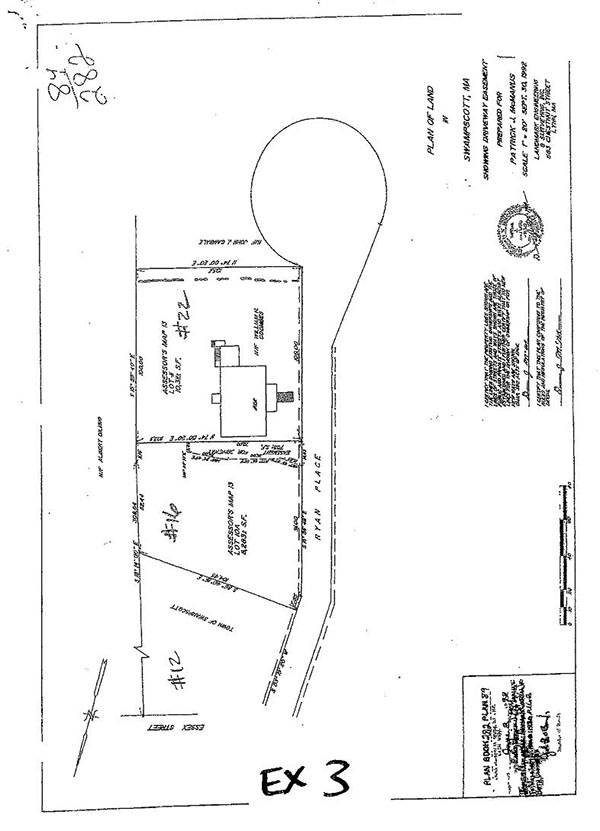

Having determined the scope of the Flynns rights as easement holders, I now turn to what rights the Colarussos have, as the servient estate, to use the portion of their property burdened by the easement. Martin v. Simmons Properties, LLC, supra, is instructive. The person who holds the land burdened by a servitude is entitled to make all uses of the land that are not prohibited by the servitude and that do not interfere unreasonably with the uses authorized by the easement or profit. An easement is a nonpossessory interest that carves out specific uses for the servitude beneficiary. All residual use rights remain in the possessory estatethe servient estate. Id. quoting Restatement (Third) of Property (Servitudes) § 4.9 comment C. As in Martin, the easement at issue in this action does not reference the full-width or require the easement be kept open throughout its full extent. Thus, the Colarussos have the right to make any and all use of their property so long as their use does not frustrate the easements purpose, which is to provide access by vehicle and by foot to the rear of the Flynns property. The Colarussos must be mindful that the easement is narrow, only 14.63 feet at its widest point. See Ex. 3, Plan of Land Showing Driveway Easement. Minor encroachments into the easement area may be permitted so long as they do not interfere with the Flynns ability to pass over the easement by vehicle and by foot. Any encroachments that impede this access must be removed immediately.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED: (1) the Flynns have the right to use the easement for access by vehicle and by foot to the rear of their property, (2) the Flynns may not park their vehicles or any vehicles owned by their tenants or visitors within the easement, (3) the Colarussos may make all use of their property so long as that use does not unreasonably interfere with the Flynns right to pass and repass over the easement by vehicle and by foot, (4) as stipulated by the parties at trial, the Flynns will move their fence so it is consistent with the record boundary shown on Exs. 1 and 4 (attached), and the Colarussos will remove the portion of their fence that encroaches into the easement as soon as practicable.

Additionally, the court issued an Order in this case on December 17, 2013 regarding actions taken by the Colarussos within the easement area while this case was under advisement. Parts 1 and 2 of that Order remain in effect and are incorporated into this Decision and Judgment. Part 3 of that Order, pertaining to parking within the easement area, is superceded by this Decision and Judgment.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

TERRANCE FLYNN and DIANE FLYNN v. MICHAEL A. COLARUSSO, JR. and HEIDI A. (SMITH) COLARUSSO.

TERRANCE FLYNN and DIANE FLYNN v. MICHAEL A. COLARUSSO, JR. and HEIDI A. (SMITH) COLARUSSO.