Introduction

In this G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal, plaintiff John Giordano seeks to remove conditions imposed on a special permit issued by the Haverhill City Council allowing him to construct a single-family dwelling at 90 Amesbury Road, 300 feet from Kenoza Lake, a City reservoir. Section 255-90 of the Haverhill Zoning Ordinance prohibits the construction of buildings within 500 feet of the mean high-water elevation of Kenoza Lake without a permit from the City Council. The Council may only grant such a permit if it finds that the proposed building does not have an adverse effect on the public water supply. Haverhill Zoning Ordinance, § 255-90. After initially denying the special permit, Mr. Giordano appealed, and this court remanded the matter back to the City Council, which then granted the special permit subject to a number of conditions. Most of these conditions were accepted, modified or stricken by stipulation of the parties prior to trial. Those that remain are the subject of this appeal. Mr. Giordano contends that the building he wishes to construct cannotby virtue of his propertys topography, sloping away from Kenoza Lakehave any adverse impact on the public water supply, and therefore, the remaining conditions are unrelated to the purpose of § 255-90 and thus unreasonable, arbitrary and capricious.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully set forth below, I find the remaining conditions at issue are not related to the protection of the public water supply, are beyond the scope of the Councils authority under § 255-90, and are thus STRICKEN in their entirety.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Section 255-90 of the Haverhill Zoning Ordinance provides:

Building near water supply

For the protection of the public water supply, no building shall be constructed within 500 feet of the mean high-water elevation within the contiguous reservoirs of Millvale Reservoir, Kenoza Lake, Johnsons Pond, Chadwick Pond, Round Pond or Crystal Lake without a permit from the City Council. Such permit may be granted if the City Council finds that the proposed building does not have an adverse effect on the public water supply. The City Council shall refer all requests for such permit to the Conservation Commission for a review and recommendation before the City Council shall vote on the request. Any application for a permit under this section shall be accompanied by a report form the Conservation Commission setting forth a record of its action on and any recommendations as to the subject matter of the application. No application shall be considered complete without such report and the time within which to act on the application shall not begin to run until such report is filed.

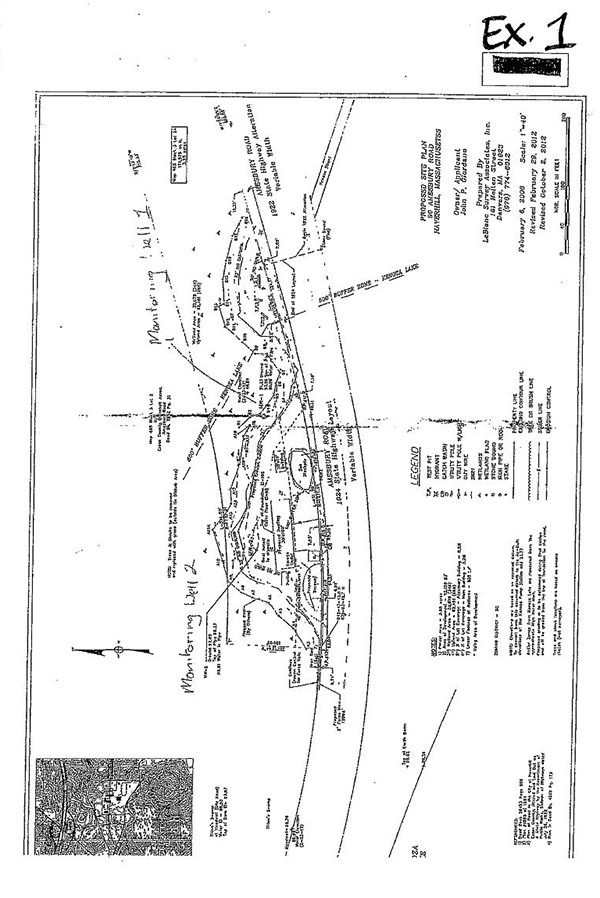

On September 17, 2010, Mr. Giordano applied to the City Council for a special permit to construct a single-family dwelling approximately 300 feet from Kenoza Lake, the Citys primary public water supply. Kenoza Lake is located to the south of Mr. Giordanos property. Amesbury Road, also known as State Highway 110, runs between Mr. Giordanos property and the Lake. See Ex. 1, attached. To the north, Mr. Giordanos property is bordered by Tiltons Swamp, which is not a public water supply. Several public hearings were held on the permit application, and on August 23, 2011, the City Council voted to deny Mr. Giordano the necessary special permit. He appealed the Citys decision to this court, which remanded the matter back to the City Council so that the Council could consider the opinion of Mr. Giordanos expert and obtain a formal recommendation from the Conservation Commission, a necessary pre-requisite to a valid Council decision under § 255-90. [Note 1]

The Conservation Commission reviewed the project at its meeting on October 25, 2012 and voted 5-0 in favor of recommending the special permit, subject to 20 conditions formulated by the Commission. See Letter from Robert Moore, Jr., Environmental Health Technician, to Margaret Toomey (Oct. 26, 2012) with Attachment B (Special Permit Conditions Recommended by the Conservation Commission). On October 30, 2012, the City Council considered Mr. Giordanos application on remand, this time voting 6-3 against his project. Notice of Decision (filed with the City Clerk Nov. 2, 2012). Shortly after that meeting, City Councillor William Ryan filed a request for reconsideration of the application. Pursuant to the Councils rules, the matter was considered once again at the next meeting, held on November 13, 2012.

At this meeting, the Council reversed its prior position and approved the special permit subject to the conditions recommended by the Conservation Commission, plus six other conditions added to the special permit by Councillor William Maceks motion to amend. Amended Notice of Decision (filed with the City Clerk Nov. 15, 2012).

Mr. Giordano filed an amended complaint in December 2012, seeking to annul all the conditions imposed by the Councils decision. Prior to trial, the parties narrowed the number of contested conditions by stipulation, accepting or modifying some and striking others. See Stipulation (Apr. 22, 2013). At the time of trial, the only conditions at issue were the following:

Conditions Recommended by the Conservation Commission [Note 2]

3. The proposed dwelling may only be used as a primary residence, with the proposed building being the only accessory structure. No other use, permitted or otherwise under the City of Haverhill Zoning Code shall be allowed.

4. The maximum total coverage of the dwelling, detached building, driveway, and parking areas shall not exceed 8,500 square feet. (Roughly 10% of the western portion of the lot)

20. The applicant, in consultation with a qualified hydrogeologist, shall install a series of groundwater monitoring wells around the property to be used in monitoring the site for the possibility of contaminants migrating from the site towards Kenoza Lake. A minimum of three (3) wells shall be installed. Groundwater shall be sampled from each well and analyzed for contaminants of concern to the Haverhill Water Department as follows:

a. Once, prior to the construction of the buildings;

b. Once, two (2) years from the date of issuance of the occupancy permit for the house; and

c. Once, every two (2) subsequent years.

Following the initial two-year monitoring period and upon written request by the applicant, the City Council may consider the elimination of this monitoring requirement if it is demonstrated that no impacts have occurred.

Conditions Added by Councillor Maceks Motion to Amend:

3. [T]he dwelling size [shall] not exceed 30 x 100 [feet] and the outbuilding not exceed 16 x 30 [feet]. No other construction shall be allowed without approval from the City Council and any other permitted SC [Note 3] use including secondary buildings or the keeping of any large animals such as horses, cows, swine or farm animals.

4. All paved travel ways, driveways, walkways, and patios shall be constructed with pervious materials, such as porous pavement, concrete pavers, or like materials. The applicant shall make every effort to remove winter sand from the pervious paved areas.

See Special Permit Conditions Summary (attached to Plaintiffs and Defendants respective Proposed Judgments, both dated July 24, 2013).

Mr. Giordano contends that because of the slope and topography of his land, the building he intends to construct will have no adverse impact on Kenoza Lake, and therefore the remaining conditions do not function to serve the purpose of § 255-90, which is protecting the public water supply.

Mr. Giordanos case rested entirely on the testimony of his expert witness, Martin Weiss. [Note 4] Mr. Weiss is a registered professional engineer who currently serves as the president of Capitol Environmental Engineering in North Reading. His past experience includes serving as the Director of Water at the Metropolitan District Commission with responsibility for overseeing the supply of water to several cities and towns in the Metro-Boston area.

Mr. Weiss testified, based on his observations of the topography of Mr. Giordanos property, that the property slopes away from Kenoza Lake toward Tiltons Swamp. He testified that surface water follows topography, and in this case would flow away from the Lake toward the Swamp. According to Mr. Weiss, ground water (also known as sub-surface water) likewise flows in the direction of the topography of the land toward the Swamp. To test this, Mr. Weiss dug two monitoring wells on the Giordano property. Monitoring Well 1, at an elevation of 91.23 feet, contained more ground water than Monitoring Well 2, located at a higher elevation of 92.69 feet, thereby confirming that the flow of ground water was, in fact, in the direction of the Swamp. See Ex.1 (depicting locations of the monitoring wells). Thus, under normal conditions, Mr. Weiss concluded that surface water and ground water from the property would flow toward Tiltons Swamp, away from Kenoza Lake, presenting no risk of adverse impact on the public water supply. I so find.

According to Mr. Weiss, ground water would only flow in the direction of Kenoza Lake during abnormal, drought conditions, when the water level of the Swamp is at a higher elevation than the water level of the Lake. To test whether a hypothetical release of contaminants from Mr. Giordanos property could reach the Lake and thus present a risk to the Citys water supply, Mr. Weiss utilized a formula, known as Darcys Law, expressed as:

v = K (h/l) / p

Darcys Law is used to calculate how fast ground water would flow in the direction of the Lake, traveling through the kind of soil conditions that exist at Mr. Giordanos property. The variables used in the formula are:

v is the average velocity of ground water.

K represents the hydraulic conductivity of the soil, i.e. the soils ability to transmit water through it, measured in feet per day. Based on his observations of the soil at the site, Mr. Weiss classified the soil as firm, fine sand. He referred to a table listing different types of soils and their associated K values. Mr. Weiss chose a value of 10 feet per day to represent K. He testified this was a conservative choice that represented soil that was actually looser, and thus had a higher degree of conductivity, than the soil he observed at the property. In keeping with this conservative approach, Mr. Weiss testified that a K factor of 10 feet per day would result in a higher velocity, and thus a greater chance that ground water from the property could reach Kenoza Lake than was actually likely to occur.

h measures the difference between the water elevation of Tiltons Swamp and the water elevation of Kenoza Lake during drought conditions. To calculate this difference, Mr. Weiss obtained data for water elevations from Kenoza Lake, recorded each day by the Haverhill Water Department for a period of 20 years, from 1991 to October 5, 2012. Unlike with the Lake, the City does not measure the water elevation of the Swamp on a daily basis, so Mr. Weiss assumed, for the purposes of his calculation, that the Swamp had an elevation of 110 feet [Note 5], a figure that is a few inches higher than the top of the Giles Road Dam at the far end of the Swamp. This was also a conservative assumption since the water elevation of the Swamp could not be above the maximum height of the dam (it would flow over it, into the stream leading away), and furthermore, during drought conditions, the water level of the Swamp would likely drop well below the top of the dam. Engineers at the Water Department told Mr. Weiss there were two periods of severe drought in Haverhill over the last 20 years, one from 1997 to 1998 and the other from 1999 to 2000. Mr. Weiss focused on two periods during these droughts when the water elevation of the Lake dropped and remained below the assumed Swamp elevation of 110 feet. The first period Mr. Weiss identified ran from July 30, 1997 to March 7, 1998 (221 days) and the second ran from July 2, 1999 to April 18, 2000 (291 days). [Note 6] Mr. Weiss then took an average of the Lake elevations from the Citys recorded data during these periods and subtracted that from his assumed Swamp elevation (110 feet). This produced a difference of 3.5 feet, which Mr. Weiss used as the h variable.

l is the distance between Mr. Giordanos proposed building and Kenoza Lake, which is 300 feet.

h/l measures the slope of the flow of the ground water from the proposed building moving in the direction of the Lake.

p is a value for the degree of porosity of the soil. Since p is the denominator in the Darcys Law formula, a smaller number results in greater velocity. Mr. Weiss again made a conservative selection, choosing a factor of .25, which is on the lower range of possible porosity values for the type of soil he observed at the property.

Mr. Weiss plugged these figures into the Darcys Law formula and calculated that during drought conditions, the velocity of ground water from the property in the direction of Kenoza Lake was .48 feet per day. He then multiplied that velocity by the number of days in each drought period and concluded that during the 1997-98 drought (221 days), ground water would travel 106 feet (221 days x .48 feet per day) and during the 1999-2000 drought (291 days), ground water would travel 140 feet (291 days x .48 feet per day). In each event, Mr. Weiss concluded that ground water from the proposed building would not reach Kenoza Lake 300 feet away.

Mr. Weiss made other conservative assumptions in these calculations. He assumed that a potential release of contaminants happened on the first day of each drought period, thus allowing for the maximum amount of time to test whether or not such contaminants could reach the Lake during drought conditions. He also assumed that the soil from Mr. Giordanos property to the Lake had the same degree of porosity throughout, although in reality, the soil under Amesbury Road was likely to be more compacted, and thus less porous, as a result of constant vehicular traffic. Mr. Weiss also assumed that these two drought periods could occur back-to-back, but even if that happened, based on his Darcys Law calculations, the ground water would travel 246 feet, still short of the Lake that is 300 feet away from the proposed building.

Based on these calculations, Mr. Weiss concluded that even during periods of extended drought, when ground water flows toward the Lake, construction on Mr. Giordanos property would not have an adverse effect on the water supply. I so find.

Analysis

In a G. L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal, the court is required to hear the case de novo, make factual findings, and determine the legal validity of the Boards decision based upon those findings. Roberts v. Southwestern Bell Mobile Sys., Inc., 429 Mass. 478 , 486 (1999) (citing Bicknell Realty Co. v. Bd. of Appeal of Boston, 330 Mass. 676 , 679 (1953); Josephs v. Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 295 (1972)). The court gives no evidentiary weight to the boards findings. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486 (citing Josephs v. Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 362 Mass. 290 , 295 (1972)). The courts function on appeal, based on the facts it has found de novo, is to ascertain whether the reasons given by the [Board] had a substantial basis in fact, or were, on the contrary, mere pretexts for arbitrary action or veils for reasons not related to the purposes of the zoning law. Vazza Properties, Inc. v. City Council of Woburn, 1 Mass. App. Ct. 308 , 312 (1973). The Board must have acted fairly and reasonably on the evidence presented to it, and have set forth clearly the reason or reasons for its decisions, in order to be upheld. Id.

Even though the case is heard de novo, such judicial review is nevertheless circumscribed: the decision of the board cannot be disturbed unless it is based on a legally untenable ground, or is unreasonable, whimsical, capricious or arbitrary. Roberts, 429 Mass. at 486 (citations omitted). When conditions imposed by the board in connection with a special permit are challenged, the court applies this standard to its review of the boards decision. [Note 7] See Capobianco v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 14 LCR 354 , 357 (2006)

In determining whether the decision was based on a legally untenable ground, the courts must determine whether it was decided

on a standard, criterion, or consideration not permitted by the applicable statutes or by-laws. Here, the approach is deferential only to the extent that the court gives some measure of deference to the local boards interpretation of its own zoning by-law. In the main, though, the court determines the content and meaning of statutes and by-laws and then decides whether the board has chosen from those sources the proper criteria and standards to use in deciding to grant or to deny the variance or special permit application.

Britton v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Gloucester, 59 Mass. App. Ct. 68 , 73 (2003) (internal citations omitted). In determining whether the decision was unreasonable, whimsical, capricious, or arbitrary, the question for the court is whether, on the facts the judge has found, any rational board could come to the same conclusion. Id. at 74. This step is highly deferential. Id. While it is the boards evaluation of the seriousness of the problem, not the judges, which is controlling, Barlow v. Planning Bd. of Wayland, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 314 , 321 (2005) (internal quotations and citations omitted); Titcomb v. Bd. of Appeals of Sandwich, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 725 , 732 (2005) (same), and a highly deferential bow [is given] to local control over community planning, Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 73, deference is not abdication; the boards judgment must have a sound factual basis. Britton, 59 Mass. App. Ct. at 74-75 (to be upheld, the boards decision must be supported by a rational view of the facts). Conditions that are unrelated to a legitimate zoning interest and fail to achieve the purpose for which they have been implemented under the zoning ordinance will be found to be arbitrary and capricious and therefore invalid. See Capobianco, 14 LCR at 358.

The sole purpose of § 255-90 of Haverhill Zoning Ordinance is the protection of the public water supply. This purpose is achieved by prohibiting construction of buildings within 500 feet of the public water supply unless the City Council finds that the proposed building will not have an adverse impact on the water supply. Conditions attached to a special permit to build within this 500 foot perimeter must, therefore, be related to eliminating potential adverse impacts on the public water supply.

Here, the uncontested evidence demonstrates that under normal conditions, surface and ground water follow the slope of the lands topography, flowing away from Kenoza Lake, and during drought conditions, ground water moving in the direction of the Lake will still fall short of ever reaching it. Because no adverse impacts have been shown to be even remotely likely, the remaining conditions at issue all suffer from the same flaw: they do not function to protect the public water supply. [Note 8] Since they do not achieve the purpose of § 255-90, I therefore conclude they are arbitrary and capricious and must be stricken in their entirety.

Mr. Giordano also objects to these conditions on other grounds, contending that they exceed the scope of the City Councils authority under § 255-90 of the zoning ordinance.

The Conservation Commissions Condition 3 provides that no use other than the particular residence approved, even if permitted under the Haverhill Zoning Ordinance, shall be allowed on Mr. Giordanos property, and Councillor Maceks Condition 3 likewise prohibits other uses, allowed in the Special Conservation district, without approval from the City Council. With respect to these conditions, Mr. Giordano rightly notes that § 255-90 only regulates the construction of buildings within 500 feet of the Lake, not uses of land within this perimeter. A different section of the Haverhill Zoning Ordinance, § 255-19, specifically authorizes the City Council to regulate land uses within the Citys Watershed Protection District. But Mr. Giordanos property does not fall within this district and is thus not subject to § 255-19. See Plaintiffs First Request for Admissions to the Defendant and Defendants Answers to Plaintiffs First Request for Admissions ¶ 31 (admitting Mr. Giordanos property not within watershed protection district).

The Conservation Commissions Condition 4, restricting coverage of the driveway and parking areas, and Councillor Maceks Condition 4, mandating the use of pervious materials for all driveways, walkways and patios, also go beyond the scope of § 255-90 which, again, only regulates buildings, not driveways, walkways or other structures.

The thrust of the Citys argument in support of these conditions is that the Council simply seeks to hold Mr. Giordano to the representations he made in his special permit application and the Council is entitled to consider reasonable conditions which could be imposed based on the use plaintiff has represented in this case. Defendants Trial Memorandum at 4. When the language of a zoning ordinance is clear and unambiguous, the ordinance will be enforced according to its plain wording. See Plainville Asphalt Corp. v. Town of Plainville, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 710 , 713 (2013). There is no mention of uses anywhere in the text of § 255-90. The Citys power to regulate land uses for the protection of the public water supply is only found in § 255-19, establishing the Watershed Protection District. As stated above, Mr. Giordanos property does not lie within that district. Any attempt to regulate uses that Mr. Giordano may pursue as of right are beyond the scope of the Citys authority under § 255-90. Moreover, the Citys goal of holding Mr. Giordano to the representations made in his application has been achieved by Conservation Commission Conditions 1 and 2, which state, respectively, that work on the property shall be performed in accordance with Mr. Giordanos site plan and that the special permit at issue only authorizes construction of a single-family dwelling. These conditions have been accepted by stipulation of the parties.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find the remaining conditions imposed by the City Council are arbitrary and capricious and are therefore STRICKEN in their entirety.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

JOHN GIORDANO v. MICHAEL HART, ROBERT SCATAMACCHIA, WILLIAM RYAN, MICHAEL YOUNG, DAVID HALL, COLIN LePAGE, MARY ELLEN DALY O'BRIEN, SVEN AMIRIAN and WILLIAM MACEK as members of the City Council of the City of Haverhill.

JOHN GIORDANO v. MICHAEL HART, ROBERT SCATAMACCHIA, WILLIAM RYAN, MICHAEL YOUNG, DAVID HALL, COLIN LePAGE, MARY ELLEN DALY O'BRIEN, SVEN AMIRIAN and WILLIAM MACEK as members of the City Council of the City of Haverhill.