Introduction

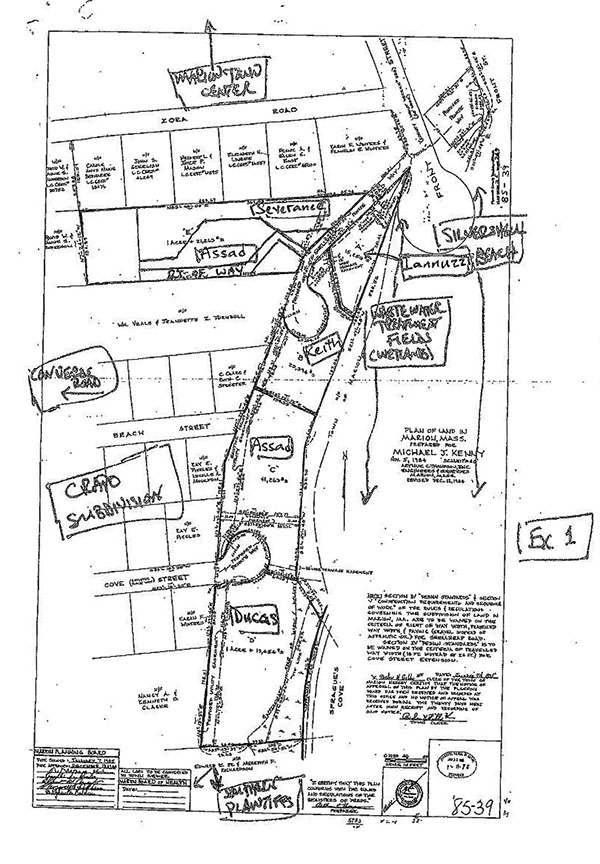

The plaintiffs [Note 2] in this case own residences near Silvershell Beach, a public beach at the end of Front Street just south of the town center in Marion. Most are in a subdivision off Converse Road developed by George Crapo in the 1950s (the Crapo subdivision), immediately to the west of the defendants homes. The remainder of the plaintiffs live in houses to the south. A plan of the area as it exists today, showing the locations of the parties and the major landmarks, is attached as Ex. 1.

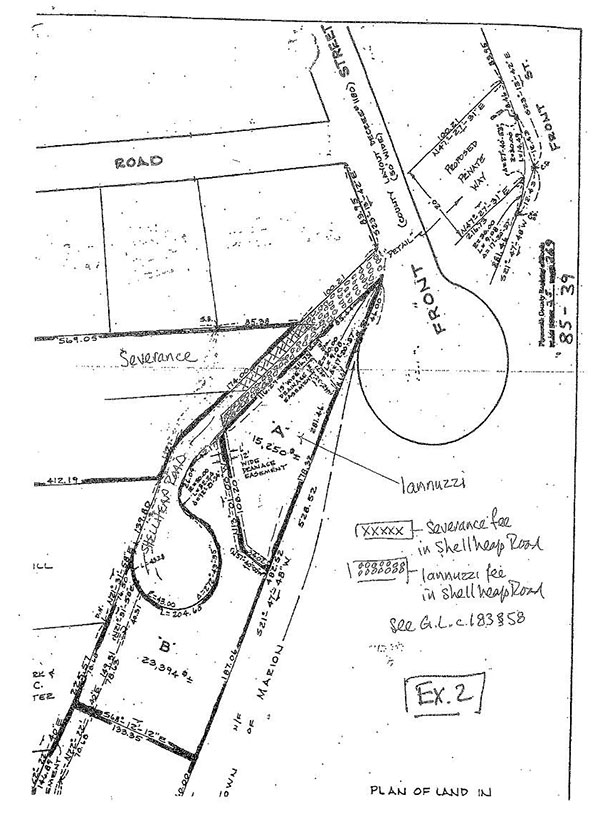

The plaintiffs can all get to the beach by using Converse Road, Zora Road, and then Front Street (all public roads) and this is, in fact, the only way to drive there. But the shortest route for each of them is by walking or bicycling through the defendants land to Front Street and then to the beach, which they claim to have done for many years. The route they use abuts the eastern boundary of the Crapo subdivision and goes along a part of the width of a former construction road, no longer existing, which the former owner of the defendants properties installed when he was dumping fill in the course of developing what is now the defendants land. [Note 3] It is currently a pathway on its southern end and, in the area presently at issue in this case [Note 4] (the far northern end, where it intersects with Front Street), a portion of the width of a private way known as Shellheap Road, owned in fee by the defendants and used by them as their shared driveway. More precisely, as more fully-explained below, in this remaining contested area, it is the western four feet of the twenty-foot width of Shellheap Road.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. I also took a view. The plaintiffs asserted two types of claims to the route in question: implied easement and prescriptive easement. The implied easement claim was made by only some of them. A prescriptive easement claim was made by all. On this claim, except for two of the plaintiffs, the defendants did not seriously dispute the long, continuous pedestrian and bicycle use of the route. Indeed, that use might never have resulted in a lawsuit had one of the walkers not kicked the Iannuzzis dog, with a resulting ugly confrontation. The real dispute was whether this use was adverse or permissive and, if adverse (with a prescriptive easement thus accruing), the width and location of the resulting easement. See Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 45 (2007) (claimant must show that his or her use was substantially confined to a regular or specific path or route for which he might acquire an easement of passage by prescription).

The Assad and Keith defendants have settled the plaintiffs claims to their sections of the disputed area by granting an express easement for pedestrian and bicycle use. The plaintiffs and the Ianuzzis, whose home is closest to the plaintiffs route and thus most affected by its use, have not settled, leaving those claims for resolution by this court. Mr. Severance was duly served but never responded, and is thus subject to default judgment.

Based on the testimony of the witnesses, the exhibits admitted into evidence at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn from that evidence, my observations at the view, and as more fully set forth below, I find and rule that none of the plaintiffs has an express or implied right to use Shellheap Road for any purpose, leaving only their prescriptive easement claims. On those, with only two exceptions (Vera Vivian and Emily Paul), I find and rule that the plaintiffs have met their burden of proving the elements necessary for a prescriptive easement to pass and repass by foot or bicycle over the western four-feet of the twenty-foot width of Shellheap Road. [Note 5], [Note 6]

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

The Background of the Crapo Subdivision and the Winters Parcel

The relevant events begin with the layout and development of the Crapo subdivision, where most of the plaintiffs have their homes.

In January 1952, George Crapo recorded a plan for a 39-lot subdivision (the Crapo subdivision) on land bordered by Converse Road on the west and property owned by Albert Winters (the Winters parcel) on the east. The Winters parcel, now divided and with certain additional property (see discussion below), is currently owned by the defendants, and is bounded on the north by Front Street, on the east by town-owned wastewater treatment fields (Silvershell Beach and its parking lot abut those fields on the east), and by Spragues Cove and privately- owned properties to the south. The plaintiffs are either residents of the Crapo subdivision or those southern properties.

The Crapo subdivision plan created two new roads, Beach Street and Cove Street, each running easterly from Converse Road and ending at a stone wall separating the subdivision from the Winters parcel. Converse Road is the only access route to the subdivision shown on that plan, and Beach Street and Cove Street are clearly shown as ending at the boundary with the Winters parcel.

The Winters parcel, accessed from Front Street on its north, was made up of three separate purchases of vacant land by Mr. Winters between 1937 and 1952. Mr. Winters was well known in Marion. He was a lifelong resident who worked as a general contractor installing water lines, roads, and building foundations, [Note 7] and would also, from time to time, purchase land which he would fill and grade for later re-sale to developers. The Winters parcel was such land and, to fill and grade it, Mr. Winters installed a construction road from Front Street all along its western edge (where it bordered the land that later became the Crapo subdivision), dumping sea shells and other materials on the roadway to make passage for his trucks and graders easier. This construction road was occasionally referenced as Shellheap Road, reflecting the materials dumped there, but more usually simply as the dirt road. For necessary clarity, I will refer to it hereafter as the construction road since it has long-since been abandoned and the actual Shellheap Road as built in final form (the private way, owned in fee by the Iannuzzi, Keith, Severance and Assad defendants, and used as the private driveway to the Iannuzzi, Keith, Severance and Assads Lot E homes) [Note 8] occupies only a small section of the former construction road at its northern end where it intersects with Front Street. The remainder of the construction road was integrated over time into the lots over which it had passed. [Note 9]

Mr. Crapo hired Mr. Winters to build out the infrastructure for the Crapo subdivision, grading and then paving Beach Street and Cove Street, [Note 10] and installing all water lines. In exchange for this work, Mr. Crapo, in 1952, conveyed the twelve easternmost lots in the subdivision to Mr. Winters. [Note 11] In connection with his infrastructure work in the Crapo subdivision, to make access easier for his construction vehicles, Mr. Winters opened up the stone wall at the bottom of Beach and Cove Streets, thereby temporarily connecting those streets with the construction road on the Winters parcel. Testimony from some of the early purchasers in the Crapo subdivision [Note 12] established that, at that time, residents would regularly walk (and themselves take advantage of the connection through the stone wall to occasionally drive) down Beach and Cove Streets and continue onto the construction road when traveling to and from the beach or Front Street. [Note 13] Pedestrian use was generally by single walkers or, if more than one, not more than two abreast. Bicycles were either single or went in single file. Based on this and all the other evidence, I infer that the pathway actually used was thus, at most, four feet wide or less and, as a regular matter, was on the side of the construction road closest to the Crapo subdivision. This was certainly true after the homes on the Winters parcel began to be constructed (the 1980s, see n. 21) since the walkers and bicyclists would respect the privacy of those homes by keeping as far from them as possible, and also before that time because it made for the shortest route and was directly alongside the remains of the stone wall between the subdivision and the Winters parcel the natural path to take, rather than ranging further into the Winters parcel land.

Although Mr. Winters did not live at the Winters parcel, use of the construction road by residents of the Crapo subdivision and neighboring properties was clearly done with his knowledge. Mr. Winters routinely drove trucks with excess fill from his other worksites down Beach and Cove Streets to the construction road where he would deposit the excess material in the parcels lower areas, thereby filling in and building up his waterview property. This continued from the 1950s until Mr. Winters death in 1980. Given his frequent returns to the area and his knowledge of the residents of this small town, I find that Mr. Winters knew that the construction road was being used for access to the beach and Front Street in the manner and by the persons just described.

There was no evidence that Mr. Winters ever granted permission to the residents of Beach and Cove Streets to use the construction road or, with the exception of the following two occasions, ever referred to such use in any conversation or communication. He posted no signs of any kind. In brief conversations, one with Ray Pickles and another with his daughter-in-law Mary Albert, [Note 14] both long-time residents in the Crapo subdivision, Mr. Winters indicated that he had no problem with people using the construction road to walk to the beach. But they did not interpret that as permission to walk in that area to the beach, and neither they nor any other witness who testified at trial believed they needed permission to use that route. Rather, they walked or bicycled there whenever they wished.

Mr. Winters never granted any express easements over the construction road to the residents of the Crapo subdivision or to any other plaintiff. None of the deeds he granted to the lots he owned in the subdivision one of which was to his own son, Franklin Winters contained any express rights over the construction road or, for that matter, any right of any kind in the Winters parcel. In fact, on January 1st of each year until his death in 1980, Mr. Winters placed a sawhorse across the Front Street entrance to the construction road, blocking vehicular access. The sawhorse never blocked foot traffic, however, and, while the plaintiffs and their predecessors respected its prohibition of vehicular traffic and never moved it or attempted to drive through it, there was always more than enough room to walk around it and they continued to do so.

1974, Mr. Winters recorded an ANR plan (the 1974 Winters plan) that proposed to divide the Winters parcel into 9 lots, all with frontage on the construction road, which was designated on the plan as an Existing Way. That designation (existing way) was clearly intended to indicate that it was an existing way solely to the Winters parcel lots; the plan does not show any roadway or other connection to the Crapo subdivision, any of the Crapo subdivision lots, or any of the properties to the south.

The 1974 Winters plan was never implemented, none of its lots were ever sold, and, by the time of Mr. Winters death in 1980, the Winters parcel was still undivided and intact. In 1984, Mr. Winters heirs sold the property to Michael Kenny. [Note 15] Before that sale was completed in June of that year, Mr. Kenny, with the permission of the Winters heirs, recorded his own ANR plan in May 1984 that divided the Winters parcel into 5 lots, A-E, all showing access and frontage on the construction road, which was now labelled Shellheap Road on the plan (the 1984 Kenny plan). [Note 16] Three things are notable about that plan. It does not show any roadway or other connection, of any kind, to any part of the Crapo subdivision or any properties to the south. It shows Shellheap Road as providing access only to the Winters parcel lots. And the plan soon changed, without ever being implemented.

Ray Pickles, who, in addition to living on Cove Street [Note 17] was also the Town Administrator at the time, testified that he spoke with Mr. Kenny about the lots as configured on the 1984 Kenny plan, saying that they might obstruct his (Mr. Pickles) view of the water. [Note 18] In response, Mr. Kenny developed a new ANR plan, recorded in 1985, which reflects what exists today (the 1985 Kenny plan). A copy is attached as Ex. 1. [Note 19] Lots A (now Iannuzzi), B (Keith) and E (Severance and Assad), and those Lots alone, are accessed by a shared driveway on that portion of the construction road, now formally named Shellheap Road. [Note 20] Lot C (owned by the Assads) and Lot D (owned by the Ducas plaintiffs) are accessed by a cul-de-sac connected to Cove Street (a public way). This is the first plan showing any roadway or other connection to any part of the Crapo subdivision and, notably, that connection is limited to Lots C and D. According to Mr. Pickles, this configuration not only preserved his (Mr. Pickles) water views (the cul-de-sac access from Cove Street meant that a house on Lot C would be pushed north, out of the Pickles homes line of sight), and also reduced Mr. Kennys costs since, instead of having to construct a properly-improved road as far as Lots C and D, he now had only to pave the short cul-de-sac connecting Cove Street. See Ex. 1. Moreover, the Planning Board allowed Mr. Kenny to use crushed stone on Shellheap Road, which extended only from Front Street to the cul-de-sac on Lot B. Id.

The Plaintiffs Use of Shellheap Road in the Area Currently in Dispute

I now focus on the use of Shellheap Road over the portions owned by the Ianuzzis and Mr. Severance (see Ex. 2, showing that ownership) because that is what remains in dispute now that the Keiths and the Assads have settled with the plaintiffs regarding the use of their land. [Note 21]

Mr. Kenny sold Lot A, now owned by the Iannuzzis, to Sarah Miquelle [Note 22] in 1988. Ms. Miquelle and her husband built a house on the lot and lived there until she sold the property to the Iannuzzis in 1995. She testified that, during the time she lived at the property, she regularly observed people from Beach and Cove Streets walking down Shellheap Road. She knew them and spoke with them, but testified that she never gave anyone permission, and no one ever asked her for permission, to walk on Shellheap Road. She never sought to interfere, despite knowing that she owned a portion of the route they were walking on, because she assumed that using it to get to and from the beach had been a long-established practice in the neighborhood. When Ms. Miquelle sold her property to the Iannuzzis in 1995 she never discussed granting permission to neighboring property owners to allow them to continue their use of Shellheap Road.

The Iannuzzis moved into their house on Lot A in June 1995. Shortly after moving in, the Iannuzzis, along with Ms. Assad [Note 23] who was then married to Michael Healy, installed a large boulder approximately 4 feet wide and 4 feet high at the entrance to Shellheap Road from Front Street. The inscription on the boulder reads, SHELLHEAP ROAD, PRIVATE WAY. The boulder is located off to the side of Shellheap Road, thereby allowing the Iannuzzis, Mr. Severance and the Keiths to get to their properties, and Ms. Assad to her portion of Lot E, by vehicle or by foot. The Iannuzzis, in conjunction with Mr. Severance, the Keiths and Ms. Assad, conduct maintenance and landscaping along Shellheap Road and split the cost for those activities. None of the plaintiffs has ever maintained or landscaped any part of Shellheap Road or the former construction road, nor made any contribution, monetary or otherwise, to such maintenance or landscaping.

The Iannuzzis use their Shellheap Road home as a vacation house, and Mr. Iannuzzi testified that he has regularly observed people carrying towels and beach items down the road to get to the beach. He assumed that they were property owners from Beach and Cove Streets and Converse Road. He never attempted to block their access, or told them (by posted notice or otherwise) that they were only able to walk there because he permitted it. The only evidence he offered on that point was his account of a party hosted by the Kosses (the then-owners of Lot C) which was held to welcome Iannuzzis to the neighborhood. Mr. Iannuzzi testified that, in response to a question, he told a small group of attendees the Streeters, Susannah Davis, and Ray and Diane Bondi-Picklesthat they could pass over his portion of Shellheap Road. Mr. Pickles and Ms. Davis denied that this conversation ever took place. [Note 24] Mr. Iannuzzi claimed that Mr. and Mrs. Pickles asked for permission because, they said, the Iannuzzis' predecessor, Ms. Miquelle, had given them permission and they wanted to be sure they still had it. But this account by Mr. Iannuzzi does not ring true. The question would not have been asked because, as Ms. Miquelle testified, she never gave anyone permission to cross her property and never objected to people using the road to go to the beach or Front Street. Moreover, Mr. Pickles and Ms. Davis, who both owned property in the subdivision, had been walking along the western side of Shellheap Road for years before the Iannuzzis purchased their property, even when there was a house there, believing they had a right to do so. Asking for permission at this late date would not have crossed their minds. Mr. Iannuzzi is simply mistaken in his memory. There may have been discussion at the party about Silvershell Beach one of the prime gathering places for Marion residents, and a center of many activities but it would not have included a request for permission to walk on what was considered the long-standing, usual route to get there.

Further facts are set forth in the analysis section below.

Analysis

When I refer hereafter to Shellheap Road, I include both the road in its present, improved form (i.e. the private road, ending in a cul-de-sac on Lot B (the Keith property), used by the defendants as their shared driveway) and also that area, prior to improvement, when it was a portion of the former construction road.

Implied Easements

Certain of the plaintiffs those in the Crapo subdivision who purchased (or whose predecessors-in-title purchased) their lots from Mr. Winters claim an implied easement over Shellheap Road by virtue of the fact that the cut-through from the Winters parcel to the Crapo subdivision, created by Mr. Winters in connection with his construction work on the subdivision, existed at the time of their conveyances and was used from time to time by the purchasers of those lots. I disagree. No such easement exists.

Implied easements are a matter of grantor intent. Mr. Winters owned both the Winters parcel and his Crapo subdivision lots at the time of those lots conveyances, to be sure. He had created a connection between the subdivision and the Winters parcel by breaching the wall to make access for his construction vehicles easier, again to be sure. But that is not enough. Unless the alleged easement, at the time of those conveyances, was intended for the benefit of those lots, was actually and openly used for the benefit of those lots, and was reasonable necessary for the enjoyment of those lots, the fact that it might be more convenient than its alternative does not create an implied easement. See Harvey Corp. v. Bloomfield, 320 Mass. 326 , 329-330 (1946).

Here, the evidence showed that the breach in the wall between the Crapo subdivision and the Winters parcel, connecting the construction road to the work he was doing in the subdivision, was made by Mr. Winters for his own construction purposes, was intended to be temporary in nature, and was not intended to create an access route for the subdivision or any of its lots, even those he owned. There is nothing to indicate that Mr. Winters intended the construction road to be a permanent one, and everything is to the contrary. His practice was to sell the land he acquired to other developers, and he would never have intended to lessen the sale value of the Winters parcel by putting in any infrastructure that that developer might find inconsistent with its development plans. None of his deeds to his Crapo subdivision lots not even the deed to his own son contain any easement rights over any portion of the Winters parcel for any purpose whatsoever. Those subdivision lots each had independent access to the beach or village center via Beach or Cove Streets to Converse Road, and from there to Zora Road and Front Street. That alternative route the one intended by Mr. Crapo when he laid out the subdivision, and clearly shown as such on the subdivision plan may have been a less convenient route, but it was, and is, fully adequate for all access purposes. Mr. Winters may not have minded that the subdivision residents made occasional use of the construction road, driving or walking, if it was still there and he was doing nothing else with it at those times, but he clearly never intended to create any permanent right to do so. Indeed, all his subsequent acts, particularly the absence of explicit granting language in his deeds and his annual installation of a sawhorse across the road to block access, are inconsistent with any such intent. In short, none of the plaintiffs has an implied easement to use Shellheap Road, or any part of the Winters parcel, for any purpose.

Prescriptive Easements

To establish a prescriptive easement over anothers land, appurtenant to a property the claimant owns, a claimant must prove use of the land in a manner that has been (a) open, (b) notorious, (c) adverse to the owner, and (d) continuous or uninterrupted over a period of no less than twenty years. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007). A claimant who has owned property for less than twenty years may tack on to successive periods of adverse use by immediately preceding owners. See Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 264 (1964). The claimant must also show that his or her use, and the use by whatever predecessor is tacked, was substantially confined to a regular or specific path or route for which he might acquire an easement of passage by prescription. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45. Each of these showings must be made individually, claimant by claimant. Ivons-Nispel v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 761-762 (1964). No matter how many individuals may have used a route and established prescriptive easements, those rights extend no further than those individuals and their individual properties; neither persons of the local community nor the general public can acquire prescriptive rights. Id.

The burden of proving every element of an easement by prescription rests entirely with the claimant. If any element remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009) (internal citations omitted). Because it is contrary to record titles, and begins in disseisin, which ordinarily is wrongful[,] [t]he acts of the wrongdoer [the claimant] are to be construed strictly and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof. Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74 , 76 (1912) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

To be open, the use must be without attempted concealment. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44 (emphasis added).

For a use to be found notorious, it must be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property and of such a character that the landowner is deemed to have been put on constructive notice of the adverse use. Id. (emphasis added).

To prove the use to be adverse, it is not sufficient to show an intention alone to claim [the area] as of right, but that intention must be manifest by acts of clear and unequivocal character that notice to the owner of the claim might be reasonably inferred. Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 842 (2008) (emphasis added) (quoting L. Jones, A Treatise on the Law of Easements, § 285 at 235) (Baker Voorhis & Co., New York City (1898)) (hereafter, Jones on Easements). [T]he nature of the occupancy and use must be such as to place the lawful owner on notice that another person is in occupancy of the land, under an apparent claim of right

Sea Pines Condo. III Assn. v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 848 (2004) (emphasis added). To create the presumption of a grant of the right of way, the circumstances attending its use must be such as to make it appear that it was established for the benefit of the claimant, or that it was accompanied by a claim of right, or by such acts as manifested an intention to enjoy it, without regard to the wishes of the owners of the land. The use must have been enjoyed under such circumstances as will indicate that it has been claimed as a right, and has not been regarded by the parties merely as a privilege, revocable at the pleasure of the owners of the soil. Jones on Easements § 266 at 220 (emphasis added) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Importantly, wherever there has been use of an easement for twenty years unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription and to authorize the presumption of a grant unless controlled or explained. Rotman, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 589 (internal citations and quotations omitted).

I begin by reviewing the use and the period of use for each plaintiff, leaving the question of its adversity (i.e., under a presumed claim of right, without permission) for later.

The Non-tacking Plaintiffs

Mary Albert, Gail Blout, Susannah Davis, Edward and Fern Flynn, George and Josephine Jennings, John and Susan Mims, Geoffrey and Kathleen Neal, Diane Bondi-Pickles, Edward and Meredith Richardson, Katherine Stanton, James Stewart, and William and Beverly Wareham have all lived at or owned their properties near Shellheap Road for twenty years or more. [Note 25] Mary Albert, Gail Blout, Susannah Davis, Edward Flynn, George Jennings, Geoffrey Neal, Ray Pickles, Diane Bodi-Pickles, Meredith Richardson, James Stewart, and William Wareham testified at trial. Their testimony regarding their activities and use of Shellheap Road was uniform and consistent. They all testified that they have used Shellheap Road, without interference, to walk to and from the beach and to Front Street when going into town, and have done so from the time they purchased their properties to the present. In particular, they have walked their dogs, taken their children and grandchildren to the beach, pushed baby strollers and ridden bicycles down the road. [Note 26] The frequency of these activities varied depending on whether the plaintiff was a year-round resident or a seasonal resident. But all agreed that whenever they were at their homes they used Shellheap Road. I credit their testimony and so find.

Mr. Jennings, Mr. and Mrs. Wareham, and Mrs. Richardson have each owned their properties for close to fifty years or more and provided testimony regarding Shellheap Roads use since that time. Mr. Jennings purchased 16 Cove Street [Note 27] with his wife in 1953 and built a house there in 1954. When he first moved to the property, the area now occupied by Shellheap Road was part of the construction road, basically bare dirt. Cove Street itself had not yet been paved. Mr. Jennings occasionally drove on the construction road to get to and from Cove Street, going through the breach in the stone wall which Mr. Winters had created for the use of his construction vehicles, but did so only for the few years before Converse Road was paved and thus was easier to drive on. Even after he stopped driving on the construction road, however, he continued to walk along it to get to the beach and also to walk into town to get the newspapers. This was much faster than the alternative route, walking up Cove Street to Converse Road then to Zora Road then down Front Street. In addition to being a longer route, Converse Road is not pedestrian-friendly. As I observed during the view, although obviously used by walkers (there was much evidence of dog-walking), Converse Road is a busy, two lane road without sidewalks. Mr. Jennings never asked for, or received, permission to use Shellheap Road and never had any conversations with the Iannuzzis or their predecessors about using the portion that crosses their property.

Mrs. Richardson owns 195B Converse Road [Note 28], which she purchased with her ex-husband in 1964. After they divorced in 1965, she lived there year-round with her children, later marrying Mr. Richardson in June 1969. Their wedding reception took place at their property on Converse Road. Approximately 125 guests parked in the parking lot at Silvershell Beach and walked down Shellheap Road on their way to the Richardsons house. After the wedding, the Richardsons moved to Westborough but have returned to their Converse Road house each year during the summer. Since 1965, when Mrs. Richardson lived in Marion year-round and then seasonally after 1969, she testified that she, her children, and now her grandchildren have always used Shellheap Road to get to Silvershell Beach; it was simply the way to the beach. No one ever told her otherwise. She never asked anyone for permission or received permission to walk along it. She has never spoken to the Iannuzzis and could not identify them by sight prior to trial.

Mr. Wareham and his wife purchased 27 Beach Street in 1960. Mr. Wareham described Shellheap Road at that time (when it was part of the construction road) as a gravel road. Like Mrs. Richardson, he testified that the whole route was simply the dirt road or the path. There was no formal understanding about who had rights to use the path; it was simply a convenient access route for people in the neighborhood to get to the beach and used as such. From 1961 to 1993 when he was working, he used the path in the evenings during the summer and on weekends to go to the beach and to town. Since his retirement, he uses the path, and the portion of it on Shellheap Road, nearly every day. When the Schuepps constructed their split-rail fence (see n. 21, supra), some residents of Beach and Cove Streets became upset, but passage by foot or bicycle on the route actually used (i.e. next to the subdivision boundary) was never blocked and that fence has remained in place. Mr. Wareham testified that he does not know the Iannuzzis, and has never obtained permission from them to use Shellheap Road.

John and Susan Mims purchased 195C Converse Road in 1973 and then conveyed it to themselves as trustees of the 195C Converse Road Realty Trust in 2011. Both Mr. and Mrs. Mims passed away during the pendency of this case, and no successor trustees had been appointed by the time of trial. The Mims property is located directly south of the Richardson property at 195B Converse Road. Mrs. Richardson testified that she was very friendly with the Mims and regularly observed them and their three daughters walking on Shellheap Road to get to the beach. According to Mrs. Richardson, the Mims continued to walk on Shellheap Road for beach access during the entire time they lived at the property.

Katherine Stanton is the final non-tacking plaintiff. She has owned 10 Beach Street since 1991. She did not testify at trial. Edward Flynn lives directly across the street from Ms. Stanton at 5 Beach Street, however, and he testified from personal observation that she uses her property seasonally during the summers. He has observed her, her husband (now deceased) and their children using Shellheap Road whenever they are at their property, since the time they acquired it.

Tacking Plaintiffs

Cynthia Bryden, Thomas Clarke and Alison Hodges, Constance Dolan, William and Sarah Ducas, Caroline Elkins, Bradley and Kathleen Enegren, Darron and Elizabeth Gibson, Elaine Holmes, Peter and Fair Alice McCormick, Thomas Owens, Emily Paul, Patricia Petit, Robert Raymond and Sharon Matzek, Geoffrey Stillwell and Ana Francisco, and Vera Vivian have owned their properties for less than 20 years, and their prescriptive easement claims over Shellheap Road depend on their predecessors use. [Note 29] Of these tacking plaintiffs, Elizabeth Gibson, Peter McCormick, Patricia Petit, and Robert Raymond testified at trial.

Much like the non-tacking plaintiffs, their testimony regarding their use of Shellheap Road did not vary significantly. Ms. Gibson testified that her husband, Darron, rides his bike down Shellheap Road roughly five days a week to go to Rams Island where he is the caretaker, and she and her two boys use that route to get to the beach and activities at Tabor Academy near the center of town. Mr. McCormick and his wife, Fair Alice, use Shellheap Road year-round when taking walks for exercise and, in better weather, to get to the beach with their children and grandchildren. They prefer Shellheap Road to Converse Road because it is more scenic and there are no cars to worry about. Before this litigation, Mr. McCormick never knew who owned Shellheap Road, and it never occurred to him that he would need permission to use that route. Ms. Petit has lived year round at 14 Beach Street since 1993. She uses Shellheap Road almost every day in the summer to bring her children to the beach and a few times a week during the rest of the year to get her mail from the Post Office in town. She has neither sought nor obtained permission from anyone to walk that way. Mr. Raymond and his wife, Sharon Matzek, use Shellheap Road to get to the beach or when riding a bicycle into town. He testified that in the evenings, he and his wife like to walk down to the beach to watch the sun set. Mr. Raymonds three children also regularly used the Road to go to the beach in the summer where they played volleyball. He has never met or spoken to Mr. or Mrs. Iannuzzi.

The following plaintiffs did not testify at trial, and instead relied on the testimony of other witnesses who have lived for several years on Beach and Cove Streets to discuss how they and their predecessors-in-title used Shellheap Road. Edward Flynn, who lives at 5 Beach Street a few doors down from the Gibsons, testified that the Gibsons predecessors, Robert and Jean OBrien and their two sons, always used Shellheap Road for beach access and when going to the playground near the beach. The OBriens lived at 11 Beach Street from 1987 to 1998. Peter and Fair Alice McCormick purchased 13 Cove Street in 1994 from Warren and Elizabeth Davis who had owned the property since 1987. George Jennings, Ray Pickles and Diane Bondi-Pickles all testified that Mrs. Davis and her two daughters used Shellheap Road to get to the beach. Ms. Bondi-Pickles used to walk with her to the beach because their children were the same age. 201 Converse Road, owned by Thomas Owens, had been owned by Arthur Griffin and his family from 1953 to 1991. Mr. Jennings and his wife knew Mr. Griffin, presumably since the early 1950s, and he testified that Mr. Griffin liked going for walks down Shellheap Road almost every day. That use continued when Arthur Griffin Jr. moved to the property, where he lived until his death in the late 1980s. Ms. Petits predecessors at 14 Beach Street were Robert and Elizabeth Cumming who lived there from 1975 to 1993. Ms. Cummings daughter, Elizabeth Cumming Dartt, testified that she used to walk with her mother down Shellheap Road when going to the beach or to town. Her mother also enjoyed swimming and would use the Shellheap Road route whenever the weather was good and the water was suitable for swimming. Mr. Raymond and Ms. Matzek acquired 10 Cove Street from Robert Merrow in 1997. Mr. Merrow purchased the property from Catherine Long and her children (who held remainder interests) in 1993. Ms. Long and her husband, Fletcher, purchased the property in 1953 from George Crapo. The Longs lived next door to Mr. Jennings at 16 Cove Street. He testified that he would regularly see the Longs and their children using Shellheap Road to get to the beach and that use continued for as long as they owned the property.

Plaintiffs Cynthia Bryden, Thomas Clark and Alison Hodges, Constance Dolan, William and Sarah Ducas, Caroline Elkins, Elaine Holmes, Emily Paul, Geoffrey Stillwell and Ana Francisco, and Vera Vivian likewise did not testify at trial, and evidence of their use of Shellheap Road and that of their predecessors was likewise presented through the testimony of other witnesses who had personally observed them.

Mr. Jennings lives across Cove Street from Cynthia Bryden, who owns 9 Cove Street in her capacity as Trustee of the 9 Cove Street Nominee Trust. Ms. Bryden purchased the property in 1994 from Moreau and Kathleen Hunt who had lived there since 1969. Mr. Jennings testified that Ms. Bryden frequently uses Shellheap Road when walking her dog or going to the beach. Prior to Ms. Bryden, Mr. Jennings testified that Moreau Hunt, who was a teacher and track coach at Tabor Academy, would go for a daily run down Shellheap Road during his retirement. [Note 30] Geoffrey Stillwell and Ana Francisco live next door to Ms. Bryden at 5 Cove Street. 5 Cove Street is shown as Lot 23 on the Crapo subdivision plan, and from 1953 to 2000, Lots 23 and 22 had been held in common ownership, first by the Arthur Griffin and his son and then by Peter and Kristin Eschauzier. [Note 31] Mr. Jennings testimony concerning the Griffins use of Shellheap Road is discussed above.

Thomas Clarke and Alison Hodges own 30 Beach Street, which was created out of portions of Lots 20 and 21 by Mr. Pickles in a 1987 subdivision. Mr. Pickles and his sister purchased the lots from Albert and Karin Winters in 1978 and they built a house that year for their mother, Mildred Pickles. Mr. Pickles testified that his mother used Shellheap Road to go to the general store and the senior center in the town where she volunteered twice a week. Mrs. Pickles lived at the property until 2004. Mr. Pickles also testified about C. Clarke and Ruth Streeter who lived at 31 Beach Street, now owned by Elaine Holmes, from 1961 to 2005. According to Mr. Pickles, the Streeters used Shellheap Road all the time to go on walks. The Streeters use was corroborated by Mr. Flynn who frequently saw them going to the beach (They were beach people). Ms. Assad also acknowledged that the Streeters were regular walkers on Shellheap Road.

Constance Dolan purchased 9 Beach Street from David Sheridan in 2010. Ms. Dolans property is next door to Mr. and Mrs. Flynn at 5 Beach Street. Mr. Flynn testified that he knew Mr. Sheridan and his wife, Joan, who died shortly after they purchased the property in 1982. Mr. Flynn testified that Mr. Sheridan used Shellheap Road to walk into town or to go to the beach. Mr. Flynn also testified that the Enegrens, who own 3 Beach Street but live for most of the year in Arizona, use Shellheap Road for walking, biking, and going into town. Before the Enegrens, 3 Beach Street was owned by Steven and Beth Sakwa. Mr. Flynn observed them on several occasions walking down Shellheap Road with their daughter to the beach. The Sakwas purchased 3 Beach Street in 2004 from the executor of the estate of Mary Wardle. Mr. Flynn testified that Mrs. Wardle used Shellheap Road close to four times a week to go downtown and to sit on the benches near the beach watching boats go by.

Caroline Elkins owns 195A Converse Road, which abuts Meredith Richardsons property at 195B Converse Road. Ms. Elkins purchased the property from Richard and Julie Neal in 2012. Prior to the Neals, 195A had been owned by Eileen Shea from 1962 to 2002. Mrs. Richardson knew Ms. Shea and testified that she and her children regularly used Shellheap Road to go to the beach.

William and Sarah Ducas own 30 Cove Street, which is shown as Lot D on the 1985 Kenny plan. (Ex. 1). They purchased the property from Philip and Joan (Lukey) Stevenson in 2010. Mr. Stevenson testified at trial that they purchased the lot (then vacant) from Mr. Kenny in 1986 and built a house, which was completed in the spring of 1988. The property served as a vacation home where the Stevensons would go on weekends from May to October. When they were at the property, they used Shellheap Road to get to the beach, walking to the center of town, or for bike riding. Mr. Stevensons characterized the frequency of their use as at least once a day whenever they were at the property. The Stevensons moved to a nearby property in 2008, but Mr. Stevenson continued to use Shellheap Road to walk his dog and check on the 30 Cove Street property from 2008 to 2010 when it was sold.

In sum, the evidence presented at trial demonstrates, conclusively, that, with the exception of Vera Vivian and Emily Paul, [Note 32] the use of Shellheap Road by each of the plaintiffs and their predecessors has been open, continuous, and uninterrupted for at least twenty years. The neighborhood was (and still is) close-knit, and the residents all knew each other, either as friends or as neighbors. As residents began moving to the subdivision, the construction road was simply a dirt road that provided a direct access route to the nearby Silvershell Beach. This was a shorter, easier, and safer walk than the alternative route up to Converse Road and down Zora Road to Front Street. [Note 33] The testimony at trial established that from early on, the neighboring residents used Shellheap Road for beach access and to get to Front Street when going into town. They did not think twice about such use because, for them, it was simply the way to get to the beach. Although not every plaintiff or predecessor-owner testified at trial, I infer from the ample testimony provided that the use of Shellheap Road was common among all those who resided in the neighborhood.

Because the use and the requisite period of use has been established, the prescriptive easement claims turn on whether the use of Shellheap Road by the plaintiffs and their predecessors has been adverse or, instead, was by permission.

The plaintiffs use has certainly been open. It has existed for over twenty years without any attempt at concealment. Indeed, the Iannuzzis predecessor owner, Ms. Miquelle, admitted that she watched walkers go by for many years and, as I have found, Mr. Winters himself was aware of it as well.

It has also been notorious sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property and of such a character that the landowner is deemed to have been put on constructive notice of the adverse use. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44.

Finally, it has certainly been adverse acts of clear and unequivocal character that notice to the owner of the claim might be reasonably inferred, Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 842; of such a nature as to place the lawful owner on notice that another person is in occupancy of the land, under an apparent claim of right

, Sea Pines Condo. III Assn., 61 Mass. App. Ct. at 848; and by such acts as manifested an intention to enjoy it, without regard to the wishes of the owners of the land

.under such circumstances [that indicated] it ha[d] been claimed as a right, and ha[d] not been regarded by the parties merely as a privilege, revocable at the pleasure of the owners of the soil. Jones on Easements § 266 at 220. And it certainly suffices to establish the presumption that,wherever there has been use of an easement for twenty years unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription and to authorize the presumption of a grant unless controlled or explained. Rotman, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 589 (internal citations and quotations omitted).

With that presumption established, it is the owners burden to negate it by showing it occurred with his or her permission. Merely observing use, and then doing nothing, does not amount to permission, express or implied. That is only acquiescence, which does not defeat the adverse claim. Rotman, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 590 (Such acquiescence, or tacit agreement, by an owner, to the adverse use of his property is not the same as granting permission and will not, by itself, defeat a claim of prescriptive rights). Contrast Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 839, 843, where the owner, Ms. Liberatore, allowed persons to share her beach, but exercised sufficient direct control a fence around her sand dunes to keep people off them, signs posted on that fence to please keep off, and direct instructions to leave the dunes, all of which were respected to show that the others were on her beach with her implied permission.

This case is not Houghton, or anything comparable. Neither Mr. Winters, nor any of his successor owners, ever gave express instructions to the plaintiffs of what they could or could not do. They assumed they could walk on the route without need of permission, and no one ever told them otherwise. The acts that were taken all related to the termination of vehicular use of the route, which the plaintiffs acknowledged and respected. After all, no formal road connection was ever made between the subdivision and the Winters parcel, only a break in the wall put there to allow Mr. Winters construction vehicles easier access to the subdivision while they were working there. Ultimately, the subdivision roads were paved. Everything beyond the break was simply dirt, and remained dirt, until the actual, non-connecting, Shellheap Road was later constructed. Mr. Winters sawhorse only blocked vehicles, not walkers or bicycles, which he had to have known continued their use. Importantly, to the extent Mr. Winters may have intended the sawhorse to affect pedestrian and bicycle use, the plaintiffs simply ignored it and continued that use, thus continuing to assert their claim of right, with Mr. Winters doing nothing further to challenge it. In these circumstances, either a G.L. c. 187, §3 notice [Note 34] or a complete barrier, sufficient to block walking and bicycling, was necessary to prevent the accrual of prescriptive rights. [Note 35]

Contrary to the Iannuzzis arguments, the fact that Mr. Winters put breaks in the stone wall at the subdivision boundary with his parcel cannot be seen as a grant of implied permission to the plaintiffs, negating their adversity. He made those breaks for his own purposes, not theirs. Had permission been Mr. Winters intent, it is likely he would have granted express easements to the purchasers of lots in the Crapo subdivision, or at least to the purchasers of the ones he owned. He did not.

The Iannuzzis contend that Mr. Kennys 1985 subdivision plan shows that he exercised control over Shellheap Road by shortening its length and having it end in a cul-de-sac on Lot B. But as Mr. Pickles testified, Mr. Kenny did not configure his subdivision plan this way with the purpose of preventing people from walking over Shellheap Road. The 1985 plan benefited Mr. Kenny by supplying his lots with the necessary frontage without having to pave the entire length of Shellheap Road as his prior, 1984 plan would have required. A path along the subdivision boundary still existed on the ground after Mr. Kenny subdivided the Winters parcel and built out the cul-de-sacs shown on the 1985 plan. Moreover, neighboring property owners continued using that path, and Shellheap Road beyond, as they always had.

The Schuepps and Keiths modified Shellheap Road by narrowing its width to prevent vehicles from driving over their properties, but importantly, they never interfered with pedestrian use, which was ongoing. The sign that the Keiths posted stating, private property, pass at own risk acknowledges the rights that had been acquired to use Shellheap Road for beach access, while at the same time limiting the Keiths potential liability to those who used the road. Mrs. Keith even sought legal counsel for the signs wording, but notably it did not say anything suggesting that passage was with the express permission of the owners, or that it had been posted to terminate any continuing accrual of prescriptive rights. See G.L. c. 187, §3.

Similarly, the Iannuzzis never took any steps to stop the residents of Beach and Cove Streets from using Shellheap Road. The boulder they and Ms. Assad installed at the entrance to Shellheap Road, which reads, SHELLHEAP ROAD, PRIVATE WAY, never deterred the plaintiffs from using the road as they always had. Their adverse use of the road continued, unchecked. The location of the boulder is also important. The Iannuzzis placed the boulder facing outward in the direction of Front Street where there is a public parking area near Silvershell Beach, which suggests it was intended to discourage members of the public visiting the beach from wandering down the road or taking a wrong turn. The boulder is not facing in the direction where the plaintiffs would be coming from.

As discussed above, I do not find it credible that Mr. and Mrs. Pickles, Ms. Davis, or Mr. and Mrs. Streeter would have asked Mr. Iannuzzi for permission to continue using Shellheap Road to get to Silvershell Beach. All of them had owned property in the Crapo subdivision for many years prior, and had neither sought nor received permission from anyone during that time to use the road.

Lastly, both Mr. Pickles and Ms. Albert testified about brief interactions with Mr. Winters where he told them that Shellheap Road was the way to the Beach. Even if this could be construed as permission, Mr. Pickles and Ms. Albert continued using Shellheap Road as they always had since 1984, when Mr. Winters heirs sold the Winters parcel to Mr. Kenny, and their use of Shellheap Road once again became adverse to Mr. Kennys ownership rights.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find that none of the plaintiffs has an implied right to use any part of Shellheap Road, but that all of the plaintiffs, except for Ms. Vivian and Ms. Paul, have established appurtenant prescriptive easement rights to walk, hand-carry objects, push strollers, and bicycle over the four foot-wide portion of Shellheap Road that crosses the Iannuzzi and Severance properties, measured from the western edge of the road. The plaintiffs shall prepare a plan, suitable for recording, that shows this easement.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

Lot C, now owned by the Assads, was bought by Paul and Linda Schuepp who built a house on the property in the mid 1980s. The Schuepps were concerned about cars driving from Front Street over Shellheap Road and the remains of the construction road to a spot near an in-law apartment where Mrs. Schuepps mother lived. They thus constructed a split-rail fence along the western boundary of Lot C about 6 to 8 feet away from the stone wall that separated the Crapo subdivision and the Winters parcel. This effectively reduced the width of the former construction road, preventing vehicular traffic, but did not affect the approximately 4 foot-wide area over which the plaintiffs had been walking and bicycling. The Schuepps bought fill and loam and extended their yard up to the split rail fence, eliminating all remains of the former construction road in that area. Gregory and Elizabeth Koss purchased Lot C from the Schuepps in 1993, but were foreclosed upon and the property was left vacant for several years. The Assads then purchased Lot C in 2011. They repaired the split-rail fence and constructed a new stockade fence (now removed) all the way to the subdivision border, blocking the pedestrian path for the first time. This lawsuit then followed.

Mr. Kenny sold Lot B to Mr. Keith, who built a home there in the 1980s. Around 1987, Mr. Keith placed two large boulders at the corner of Lots B and C, thereby blocking any possible vehicular access from Beach Street (the Schuepps split-rail fence, discussed above, was located between Beach and Cove Streets and thus did not prevent potential vehicular access from Beach Street). The boulders left approximately six feet of space along the subdivision border, and thus did not affect the approximately 4 foot-wide area over which the plaintiffs had been walking and bicycling. None of the plaintiffs are pressing a claim for vehicular access, and the evidence showed that there were only a few cars attempting to drive from the Crapo subdivision into the area of the former construction road by the late 1980s. In the mid-1990s, Mr. Keith also installed a post with a sign reading PRIVATE PROPERTY, pass at own risk at the corner of Lot B and Lot C.

The conclusions I draw from this are these. The plaintiffs have no prescriptive right to vehicular access of any kind, as evidenced (among other things) by their acceptance of barriers blocking vehicular use. Indeed, they do not assert such rights in these proceedings. More to the point, by their acceptance of the narrowing of the former construction road to a few feet along the edge of the Crapo subdivision, only bringing suit when a fence was built that went all the way to that edge, the plaintiffs recognize that their prescriptive rights, if any, are limited to whatever width is needed along that edge to enable them to pass and repass by foot and bicycle. This is consistent with my finding that the area so used in the past, and thus prescriptively occupied, is a 4 foot wide strip bordered on the west by the boundary of the Crapo subdivision.

The plaintiffs concede that Vera Vivian and Emily Paul cannot meet the required elements for an easement by prescription. When Ms. Vivian purchased 28 Cove Street in 1994 and when Ms. Pauls predecessor purchased 16 Beach Street in 1993, both lots were vacant land. Thus, Ms. Vivian and Ms. Paul cannot show twenty years of use.

MARK FANTONI, [Note 1] et al, v. SHAY ASSAD, CHRISTINE ASSAD, JONATHAN KEITH, KRISTEN KEITH, FREDERICK SEVERANCE, RALPH IANNUZZI and ANA IANNUZZI.

MARK FANTONI, [Note 1] et al, v. SHAY ASSAD, CHRISTINE ASSAD, JONATHAN KEITH, KRISTEN KEITH, FREDERICK SEVERANCE, RALPH IANNUZZI and ANA IANNUZZI.