Introduction

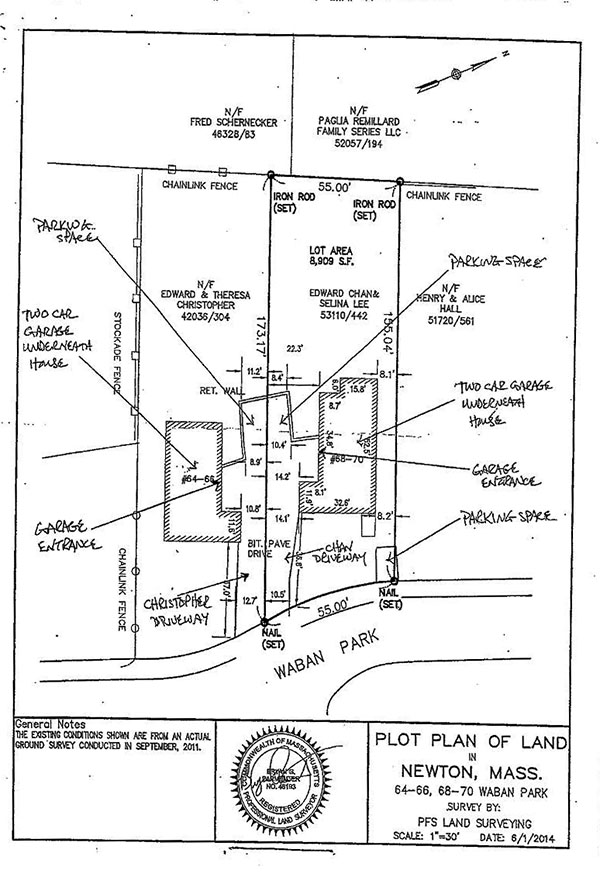

Plaintiffs Edward and Theresa Christopher, at first individually, then as trustees of the Hill Top Waban Realty Trust, and now individually again [Note 1] (the Christophers), and defendants Edward Chan and Selina Lee (the Chans), own abutting two-family homes in Newton 64/66 Waban Park (Christopher) and 68/70 Waban Park (Chan). The Chans live in one of the units in their two-family home, renting the other unit to tenants. The Christophers have always lived elsewhere (Wellesley), and rented both their units to tenants. Each of the houses has a two-car garage underneath the house and an additional parking space outdoors, just past the garages, located at the back end of the driveway. See Ex. 1 (surveyed plot plan). The Chans also have another outdoor parking space in their front yard, directly off the street. Id. Each of the houses has its own driveway, more than wide enough for unobstructed passage to its house. Id. The two driveways have been paved together, however, leading to the present dispute.

Put briefly, that dispute is this. To maximize the income from their building, the Christophers typically rent to six tenants, often students four in the upstairs unit, and two in the downstairs unit. Attracting and maintaining such density is easier if there is off-street parking for each tenant, and the Christophers have thus told their tenants that they can park in the Christopher driveway (long enough to fit three cars if parked in tandem, one behind another) as well as in the garage and the space at the back. When cars park in the driveway, however, particularly when more than one does so, cooperation is necessary. Those who park there must be prepared to move their cars (either themselves, or by leaving their keys behind for their roommates to access) when others wish to enter or exit. While this might not be a frequent event (the testimony suggested that the Christophers tenants keep different schedules, and adjust their parking accordingly), [Note 2] having to move those cars is not as convenient as simply driving around them by using the Chans driveway if, of course, that driveway is open.

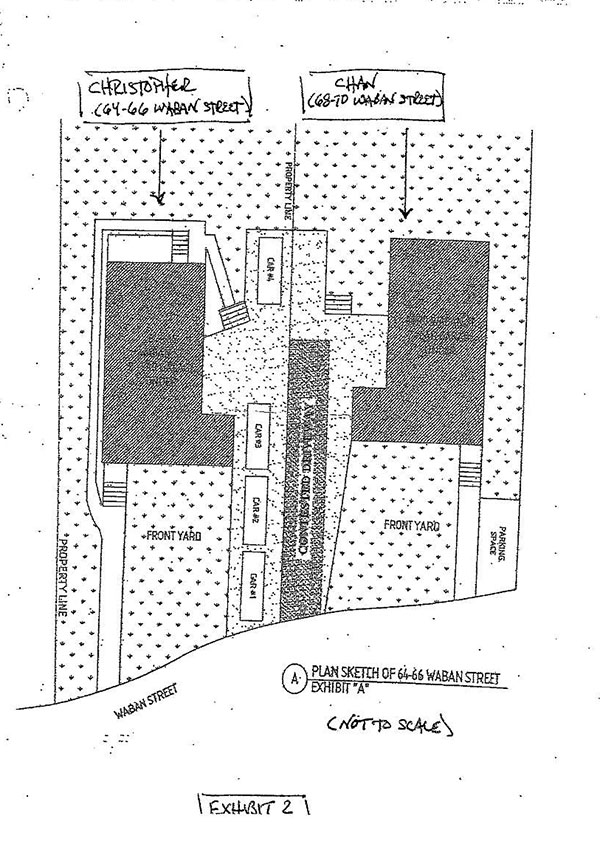

The Chans do not mind this use of their driveway, if it is open. But they and their tenants often park there, as did the prior owners and tenants of their house. [Note 3] They may also leave objects in their driveway from time to time in the ordinary course of their lives lawn mowers, childrens toys, bicycles and the like. The Christophers do not want this, and have brought this action seeking a permanent injunction directing the Chans to keep the Chan driveway clear and unobstructed at all times for the Christophers tenants use, while allowing those tenants to park in the Christophers driveway, anyplace and anytime, without restriction in short, a contention that I can, you cant. See Ex. 2 (cars #1, #2 and #3 and contested driveway). The

Christophers have no express right to use the Chans driveway, far less to insist that it be kept open and unobstructed at all times for their unrestricted use. Instead, they allege they have a prescriptive easement giving them such rights, and an implied easement by necessity to those rights as well. The Chans deny that any such rights or easements exist.

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based on the testimony and documents admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and appropriate inferences to be drawn from that evidence, and as more fully explained below, I find and rule that the Christophers have failed to prove their claims. Their complaint is thus DISMISSED in its entirety, with prejudice.

Prescriptive Easements

To establish a prescriptive easement, a claimant must prove use of the land in a manner that has been (a) open, (b) notorious, (c) adverse to the owner, and (d) continuous or uninterrupted over a period of no less than twenty years. Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43-44 (2007). The claimant must also show that his or her use was substantially confined to a regular or specific path or route for which he might acquire an easement of passage by prescription. Id. at 45.

The burden of proving every element of an easement by prescription rests entirely with the claimant. If any element remains unproven or left in doubt, the claimant cannot prevail. Rotman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009) (internal citations omitted). Because it is contrary to record titles, and begins in disseisin, which ordinarily is wrongful[,] [t]he acts of the wrongdoer [the claimant] are to be construed strictly and the true owner is not to be barred of his right except upon clear proof. Tinker v. Bessel, 213 Mass. 74 , 76 (1912) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

To be open, the use must be without attempted concealment. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44 (emphasis added).

For a use to be found notorious, it must be sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property and of such a character that the landowner is deemed to have been put on constructive notice of the adverse use. Id. (emphasis added).

To prove the use to be adverse, it is not sufficient to show an intention alone to claim [the area] as of right, but that intention must be manifest by acts of clear and unequivocal character that notice to the owner of the claim might be reasonably inferred. Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 842 (2008) (emphasis added) (quoting L. Jones, A Treatise on the Law of Easements, § 285 at 235) (Baker Voorhis & Co., New York City (1898)) (hereafter, Jones on Easements). [T]he nature of the occupancy and use must be such as to place the lawful owner on notice that another person is in occupancy of the land, under an apparent claim of right

Sea Pines Condo. III Assn. v. Steffens, 61 Mass. App. Ct. 838 , 848 (2004) (emphasis added). To create the presumption of a grant of the right of way, the circumstances attending its use must be such as to make it appear that it was established for the benefit of the claimant, or that it was accompanied by a claim of right, or by such acts as manifested an intention to enjoy it, without regard to the wishes of the owners of the land. The use must have been enjoyed under such circumstances as will indicate that it has been claimed as a right, and has not been regarded by the parties merely as a privilege, revocable at the pleasure of the owners of the soil. Jones on Easements § 266 at 220 (emphasis added) (internal citations and quotations omitted).

[W]herever there has been use of an easement for twenty years unexplained, it will be presumed to be under claim of right and adverse, and will be sufficient to establish title by prescription and to authorize the presumption of a grant unless controlled or explained. Rotman, 74 Mass. App. Ct. at 589 (internal citations and quotations omitted). However, [e]vidence of express or implied permission rebuts the presumption of adverse use. Id. (emphasis added). The essence of nonpermissive use is lack of consent from the true owner. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145 (2000) (internal citations omitted).

Whether a use is nonpermissive depends on many circumstances, including the character of the land, who benefited from the use of the land, the way the land was held and maintained, and the nature of the individual relationship between the parties claiming ownership. Totman, 431 Mass. at 145 (internal citations omitted). When the use began with permission, there is and should be a heavy burden [on the claimant] to show by clear evidence that the use has shifted at some point from permissive to adverse, so as to put the owner on clear notice that he should take steps to protect his rights. Begg v. Ganson, 34 Mass. App. Ct. 217 , 221 (1993).

Where the claim of prescription is for access over land purposely left open by its owner for his or her own purposes (here, the Chans and their predecessors unobstructed access to their own garage and rear parking area), its use by others, unless accompanied by a claim of right, is generally presumed to be permissive. See Kilburn v. Adams, 48 Mass. 33 (1843). Kilburn involved Groton Academy and its practice of leaving the sidewalks throughout its campus open for public use. The plaintiff, who was accustomed to using those sidewalks to get from his home to the highway in front of the Academy, claimed that his continuous use entitled him to a prescriptive easement and barred the Academy from blocking his way in any manner. The Supreme Judicial Court disagreed, holding:

The question is, whether the plaintiffs, owners of an estate adjoining the academy lot, acquired a right of way over that lot, by the adverse and uninterrupted use of such way, by themselves and the former owners and occupiers of the estate, under the circumstances set forth in the report. The rule we think is, that where a tract of land, attached to a public building, such as a meeting house, town house, school house, and the like, and occupied with such house, is designedly left open and unenclosed, for convenience or ornament, the passage of persons over it, in common with those for whose use it is appropriated, is, in general, to be regarded as permissive, and under an implied license, and not adverse. Such a use is not inconsistent with the only use which the proprietors think fit to make of it; and, therefore, until they think proper to enclose it, such use is not adverse, and will not preclude them from enclosing it, when other views of the interests of the proprietors render it proper to do so. And though an adjacent proprietor may make such use of the open land more frequently than another, yet the same rule will apply unless there be some decisive act, indicating a separate and exclusive use, under a claim of right

any plain, unequivocal act, indicating a peculiar and exclusive claim, open and ostensible, and distinguishable from that of others.

Kilburn, 48 Mass. at 38-39 (emphasis added). See also Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 841 (citing Kilburn for the proposition that, because of the difficulty in overseeing and monitoring the use of open and unenclosed land, claimants of adverse rights in such property must show some decisive act, indicating a separate and exclusive use, under a claim of right

open and ostensible and distinguishable from that of others); Sprow v. Boston & Albany R.R., 163 Mass. 330 , 339-340 (1895) (If one in walking or driving finds a way open before him, and uses it because it seems to be intended for such use, this alone does not show that he uses the way as a matter of right, and such use would not establish a prescriptive right, no matter how frequent or how long continued it might be. Merely from using what is open to use, without more, no presumption arises that the use is adverse.).

Finally, the adverse, non-permissive acts must continue uninterrupted for twenty years or more, either by the claimant or his predecessors in title. See Wishart v. McKnight, 178 Mass. 356 , 360 (1901); G.L. c. 260, §§21-22. While continuous use does not necessarily mean constant use, the claimant must establish a use that is regular throughout the twenty-year period. Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870) (internal quotations omitted). Whatever breaks the continuity of the possession and enjoyment of an easement, whether by a cessation to enjoy it, or by any act of the owner of the servient tenement, destroys altogether the effect of the previous user. Pollard v. Barnes, 2 Cush. [56 Mass.] 191, 199 (1848) (cited and quoted in Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45). See also Wishart, 178 Mass. at 360 (Where possession of land has been held for the statutory period by successive disseisors or trespassers, the defense of the statute is not made out if the possession has not been continuous, because where a disseisor in fact abandons his possession and leaves the land vacant, the seisin of the true owner reverts; there is a new departure from that time, and the owner can rely on his new seisin by reverter as the ground of an action within the statutory period.) (internal citations omitted).

Implied Easements by Necessity

In addition to their claim of a prescriptive easement, the Christophers allege that they possess an implied easement by necessity. Such an easement is implied (or, more precisely, presumed to have been intended) when a parcel is conveyed out of land under common ownership and the land retained by the common owner would be landlocked without access over the land he conveyed. See Town of Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 77 (2004). Similarly, [a] right of way of necessity over land of the grantor is implied by the law as a part of the grant when the granted premises are otherwise inaccessible, because that is presumed to be the intent of the parties. The way is created, not by the necessity of the grantee, but as a deduction as to the intention of the parties from the instrument of grant, the circumstances under which it was executed and all the material conditions known to the parties at the time. Orpin v. Morrison, 230 Mass. 529 , 533 (1918).

The burden of proving the intent of the parties to create an easement which is unexpressed in terms in a deed is upon the party asserting it. Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 105 (1933). As the courts have noted, [i]t is a strong thing to raise a presumption of a grant in addition to the premises described in the absence of anything to that effect in the express words of the deed. Orpin, 230 Mass. at 533. Thus, [s]uch a presumption ought to be and is construed with strictness. Id. While the necessity which gives rise to the presumption need not be an absolute physical necessity, it must be a reasonable necessity. Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp, 284 Mass. at 105. Importantly, the right to such an easement ends when the necessity no longer exists. See Hart v. Deering, 222 Mass. 407 , 410 (1916) ([W]here the necessity for such a way ceases, the right is at an end); Viall v. Carpenter, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] 126, 127 (1859) (Assuming that the defendant once had a right of way of necessity, that right ceased when the necessity ceased by his having access to the locus over his other land); Baker v. Crosby, 9 Gray [75 Mass.] 421, 424 (1857) (acquisition of other land, removing the necessity, ended easement by necessity); Burlingame v. Gay, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1135 , 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 (Jun. 7, 2013) (unpublished Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) and cases cited therein (same).

A variant of such an easement, also argued by the Christophers, is easement by implication from pre-existing use, again dependent upon necessity. As the case law describes it, [w]here during the common ownership of a parcel of land an apparent and obvious use of one part of the parcel is made for the benefit of another part and such use is being actually made up to the time of severance and is reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the other part of the parcel, then upon severance of the ownership a grant to continue such use may rise by implication. Sorel v. Boisjolie, 330 Mass. 513 , 516 (1953). Again, the easement must be reasonably necessary. Id. And again, the right to such an easement ends when the necessity no longer exists. See Burlingame, 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 and cases cited above. Reasonable necessity does not exist if the party claiming the easement has access to his land from another parcel. Id.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

Both the Christopher and the Chan properties are on land acquired by Alexander Marvin from George and Alonzo Weed, trustees under the will of Charles W. Emerson, by deed dated June 22, 1925. Mr. Marvin subdivided the property into six lots, including the directly abutting lots now owned by the Christophers (64-66 Waban Street) and the Chans (68-70 Waban Street). See Ex. 1. He also constructed the two-family dwellings that currently exist on those lots. Id.

The first of those two lots to be sold was the now-Christopher property, which was purchased by Paul and Claire Ladabouche on December 10, 1925. That deed neither granted nor reserved any easements. The Ladabouches lived in one of the units in that dwelling, renting out the other, until 1983, when they sold the house to Frank and Margaret Pettorossi. The Pettorossis lived in one of the units, renting out the other, until they sold the house to the Christophers in 1985. [Note 4] So far as the evidence showed, the Christophers were the first owners not to live in the house, and the first to rent it at its present high density.

Mr. Marvin sold the now-Chan house to Sanford and Honoria McLean in 1926, after he sold the now-Christopher house. Once again, the deed neither granted nor reserved any easements. Through several intermediate inheritances and conveyances, Richard and Allan Butler (grandsons of the McLeans) acquired the property on September 10, 1987 [Note 5] and, on June 30, 2009, sold it to the Chans. For purposes of this case, the most important of those prior owners was Marie Butler, Richard and Allans stepmother, who lived there with her husband Joseph (Richard and Allans father) from the time they married (1971) [Note 6] until his death in December 1986, and thereafter under a life-tenancy until her death on November 21, 2008 at the age of 96, [Note 7] driving and parking her car until the end. [Note 8]

1925-1982

The Christopher house and the Chan house were both constructed in 1925. Each was, and is, a two-family residence, with a two-car garage located underneath. See Ex. 1.

There are no survey plans showing the original driveways leading to those garages. Richard Butler, who lived either in or near the now-Chan house from 1935-1958 and was a regular visitor thereafter (and, much later, co-owner by inheritance) [Note 9] until it was sold to the Chans in 2009, recalls there being a single driveway, approximately ten feet wide, grass on each side, which straddled the boundary between the two houses, approximately half on each side, and was used by both, with branches to their respective garages. [Note 10] The two parking spaces at the back, one for each house, were constructed in 1972/74 [when] people were starting to have two cars. [Note 11] See Ex. 2 (space identified as Car 4 and its corresponding space on the Chan side).

Around the same time, Mr. Butlers father created another parking space, this one in his front lawn (the now-Chan property) with separate, direct access to the street. See Ex. 1. Neither the Christophers nor their predecessors have ever put a similar space on their property.

According to Mr. Butler, this single driveway configuration existed until 1982. [Note 12] There was nothing preventing the widening of the driveway on either side, and there was more than enough space to do so on both sides. Rather than widening at this time, however, the then- owners of the two houses cooperated with each other, both using the single driveway and sharing snow-removal burdens. There was no evidence that either set of owners ever claimed the right to drive over the others property or made such a claim known to the other. Instead, as Mr. Butler testified, this mutual sharing was by agreement and permission part of being a good neighbor. [Note 13] Certainly, neither gave the other an express easement to do so, and I find that all such use, both then and (as discussed below) thereafter, was permissive. Moreover, there was never any need to drive over the others property since, as just noted, there was plenty of space for widening on both sides. As discussed below, to the extent either set of owners felt they could not deny the other the mutual use of the effectively-single driveway during this time when no other access to the garages had been constructed, that feeling ended in 1982.

1982-present

As the evidence showed, there were relatively few cars using the driveway prior to 1982. [Note 14] There were thus few conflicts as cars went in and out or stopped to load, unload, and perhaps to park for short periods of time. By 1982, however, with the number of cars increasing, the owners decided to widen the paved driveway space into its current configuration, giving each of them more than enough room on their own property for free and unobstructed passage. See Ex. 1. Thus, although the driveways remained paved together, each house now effectively had its own separate driveway. The only need to use any of the others land was in the area towards the back between the garages, which the parties kept open to allow cars exiting the garages to swing around and drive out to the road, nose first. See Ex. 1. As a matter of courtesy, the then-owners had no objection to the other using their driveway, on occasion, when entering or exiting, if the driveway was clear at that time. [Note 15] I find that this was a permitted use, and not done out of any sense of obligation or in response to any demand by the other. [Note 16]

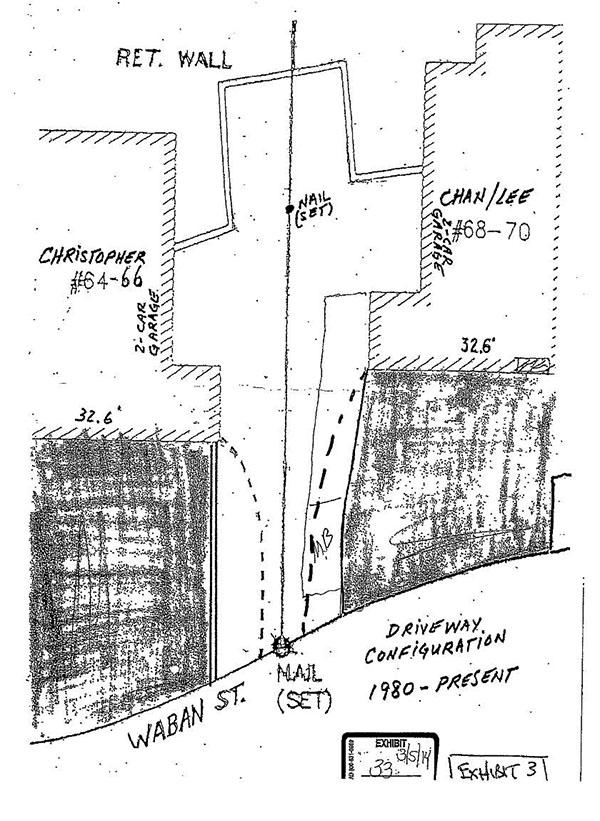

Perhaps the strongest evidence of this was the conduct of Marie Butler, who lived in the now-Chan house from 1971 until her death in 2008, first as Joseph Butlers wife and then, after his death in 1986, as the life-tenant. As testified-to by the neighbor, Carolyn Hall, Ms. Butler, who typically parked in the front lawn space on the now-Chan property, would park her car in the driveway for weeks at a time when she went on extended vacations. [Note 17] Ms. Hall recalled at least three such occasions in 1994, when Ms. Butler parked in the driveway for over a month while she was in the Caribbean, [Note 18] again a few years later (this time for two or three weeks) when Ms. Butler took a European trip, [Note 19] and a third time in the late 1990s/early 2000s (again for two or three weeks) while she took another trip. [Note 20] As that extended parking showed, Ms. Butler felt no obligation to keep her driveway unobstructed for the Christophers use, and there was no evidence that the Christophers ever insisted that her car be removed or took steps to remove it themselves. Ms. Hall also testified (as corroborated by the testimony of the former tenant, Robert Cyr) that the tenants in the Butler (now-Chan) house regularly parked in the driveway, both in the space marked MB and in the area in front of it enclosed by the hand-drawn rectangle on Ex. 3. [Note 21] Again, there was no evidence that the Christophers ever insisted that those cars be removed or took steps to remove them themselves.

As noted above, the Christophers purchased their property in 1985 and began renting both its units, typically to six tenants. Each generally had a car, and presumably had visitors with cars as well. This led to the tenants consistent parking in the Christopher driveway, tight against the retaining wall along its edge, which the Christophers told them they could do Similarly, as noted above, the tenants in the then-Butler/now-Chan house were regularly parking in the Chan driveway in the contested driveway area. [Note 22] Each could enter and exit using their driveway only, but this involved moving any cars in that driveway that were in their way obviously less convenient than using the others driveway if it was free. Over time, an accommodation was reached. Both sides would park to the side of their driveway, tight to the side, and would stagger their cars so that the ones on the other side could move easily in and out. [Note 23] I find that this was done by mutual permission, and not as a matter of right or asserted right. There was no evidence of any such assertion, and no evidence of any acknowledgement of such right.

The Chans purchased their property in 2009. Their deed does not reflect any easement benefiting the Christopher property (as the parties admit, there is no express easement) and they were not told that any type of easement might exist. The first they heard of such a claim was in 2011, years after their purchase, when Mr. Christopher made that contention in a conversation with Mr. Chan. [Note 24] Mr. Christopher contends that the Chans acknowledged the validity of his claim on that occasion, but the Chans deny this. I believe the Chans. The Chans have no problem with the Christophers tenants using the Chans driveway to enter and exit at any time the driveway is open and unobstructed, but they insist on their right to park there and leave objects in it whenever they chose.

Further facts are set forth in the Analysis section below.

Analysis

As noted above, the Christophers claim a prescriptive easement over the Chans driveway and an implied easement by necessity through prior use as well. They seek a permanent injunction directing the Chans to keep the Chan driveway clear and unobstructed at all times for the Christophers tenants use, while allowing those tenants to park in the Christophers driveway, anyplace and anytime, without restriction. With the exception of the area directly between the garages where a reciprocal easement exists and is not contested by either party, I find that no such easement or rights exist and deny the requested relief.

No prescriptive easement exists because, as discussed above, the past use of the Chan driveway or any part thereof was permissive, not adverse. Moreover, after the current driveway was created in 1982 (the driveway over which prescriptive rights are claimed, see Ex. 2), its use by the owners and tenants of the Christopher property was never continuous and uninterrupted for twenty years or more.

For purposes of analysis, there are two periods: pre-1982 and post-1982 Before 1982, there effectively was a single driveway for the two properties, straddling the boundary line between both, approximately five feet on each side. Even had its use been adverse rather than (as I find) permissive, any prescriptive rights that might previously have accrued over the five feet of the others property were clearly mutually abandoned in 1982 when the route to the garages was widened. The widening created two driveways, and the owners of each home began parking in their respective driveways. Such parking behavior is inconsistent with a right of unobstructed passage. Cars are simply too wide to easily pass unhindered down the center of the driveway when cars are parked on both sides. See Ex. 1 (showing driveway widths). See Lund v. Cox, 281 Mass. 484 , 492-493 (1933) (Physical obstructions on the servient tenement, rendering user of the easement impossible and sufficient in themselves to explain the nonuser, combined with the great length of time during which no objection has been made to their continuance nor effort to remove them, are sufficient to raise the presumption that the right has been abandoned and has now ceased to exist.).

With respect to the post-1982 period, the Christophers cannot claim accrual of prescriptive rights over an area, created by the widening, which did not exist before that date. At the earliest, any accrual thus begins in 1982. Even had that area been used adversely rather than (as I find) permissively in 1982 and thereafter, there has never been twenty years of continuous, uninterrupted use. As previously discussed, in addition to the regular tenant parking noted above, on at least three occasions (1) 1992, (2) three or four years after that (1995/1996), and (3) in the late 1990s/early 2000s Marie Butler parked her car in such a way as to block the use of the now-Chan driveway for weeks at a time. Each of those occasions was sufficient to interrupt any accrual period, see Pollard, 2 Cush. [56 Mass.] at 199, and there has never been a twenty year period between those interruptions.

No implied easement by necessity exists, nor an implied easement by necessity through prior use, because the easement claimed is for access, and there was never any necessity for such an easement. See Hart, 222 Mass. at 410; Viall, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] at 127; Baker, 9 Gray [75 Mass.] at 424; Sorel, 330 Mass. at 516 (1953); Burlingame, 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 (unpublished Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) and the cases cited therein, all as discussed above. As previously discussed, there has always been more than enough land on each property to create a sufficiently wide, separate driveway for each property, and if any necessity ever existed it ceased to exist with the reconfiguration in 1982. As noted above, that reconfiguration created two driveways, each sufficient for the house it served. If the Christophers choose to use theirs for parking, that is their right. But it comes with a consequence. Either those who are blocked by those cars simply accept that they are blocked and make alternative arrangements, or the blocking cars must be prepared to move. [Note 25] The Christophers cannot offload the burden of that consequence on their neighbors (the Chans) by prohibiting those neighbors from doing the very thing (driveway parking) that the Christophers do.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, with the exception of a reciprocal easement, binding upon both parties, to keep the area between their garages free from obstructions so that cars backing out of those garages can swing to point down the driveway to exit (an easement conceded by both parties), the Christophers claims are DISMISSED in their entirety, WITH PREJUDICE. Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

I also note an obvious point. Mr. Butler did not base his testimony on anything he was told by his grandparents, his parents, his stepmother Marie (the life tenant of the property after his fathers death), or any other owner of the property. He also never had a conversation with the owners of the other house about the use of the driveway. He himself did not acquire ownership of the now-Chan house (only a remainder interest) until his stepmothers death in 2008, and then sold it to the Chans the next year. Whatever statements he may have made about driveway rights are thus nothing more than his assumptions (which he readily admits, see Butler deposition at 119-120), and neither indicative of, nor binding upon, for example, Marie Butler (his fathers wife, and thereafter the life tenant of the property) whose conduct, as discussed below, is directly contrary to the rights claimed by the Christophers.

Only one former tenant of the Christopher house testified (Kenneth Porter), who did so by deposition (received into evidence by stipulation). He confirmed that tenants in the Chan house regularly parked in the Chan driveway. Interestingly, he said that he never had trouble getting in or out, using only the Christopher driveway, because the Christopher tenants all had different schedules. He would come home after work, drive straight down the Christopher driveway to the area in front of the Christopher garage, do a K turn so that the nose of his car faced the street, and then drive straight down the Christopher driveway to park tight against the wall in the area closest to the street, giving him direct, unobstructed access to the street when he left for work the following morning. See Porter deposition at 19.

EDWARD and THERESA CHRISTOPHER as trustees of the HILL TOP WABAN REALTY TRUST v. EDWARD CHAN and SELINA LEE.

EDWARD and THERESA CHRISTOPHER as trustees of the HILL TOP WABAN REALTY TRUST v. EDWARD CHAN and SELINA LEE.