Introduction

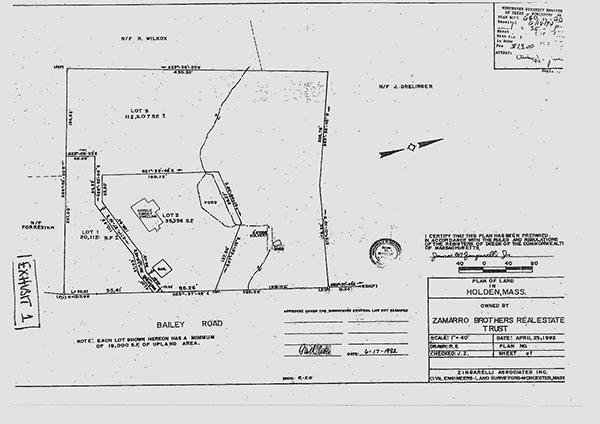

Plaintiffs Michael and Marie-Anne Lavallee (the "Lavallees"), defendants Kieran and Leslie McGee (the "McGees"), and third-party defendants Jeffrey and Kim Ann Frysinger (the "Frysingers"), own abutting properties on Bailey Road in Holden. The properties were all once part of a larger parcel owned by the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust, which subdivided the property into these three lots. Currently, Lot 1 is owned by the Lavallees (231 Bailey Road), Lot 2 is owned by the Frysingers (223 Bailey Road), and Lot 3 is owned by the McGees (227 Bailey Road). See Ex. 1 (attached). When the property was subdivided, Lot 3 was configured to include an access strip to Bailey Road, running between Lots 1 and 2 (referenced hereafter as the "deeded driveway"). See Ex. 1.

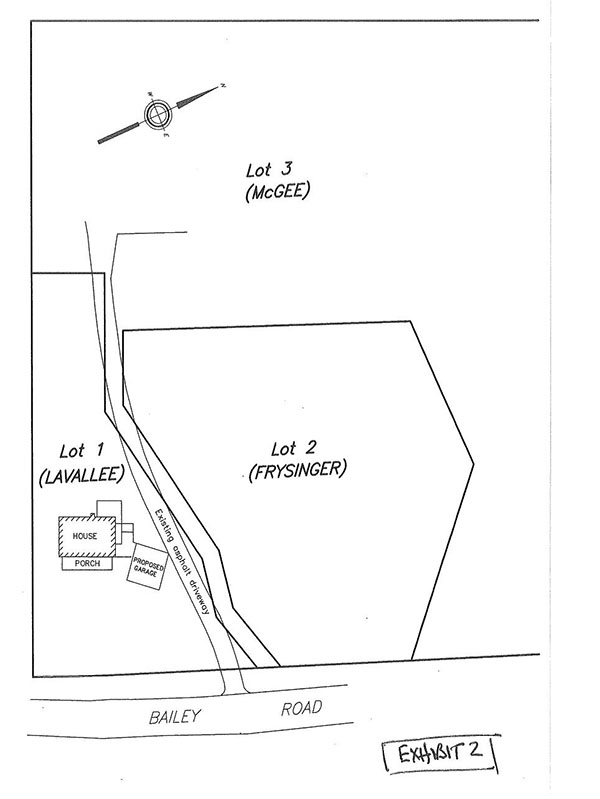

The dispute between the parties is this. The present driveway to Lot 3 (the "existing asphalt driveway" shown in the attached Ex. 2) strays outside the boundaries of the deeded driveway and encroaches on the other lots. See Ex. 2.

The Lavallees discovered the encroachments when they had a survey done in connection with construction of a proposed garage. See Ex. 2. If the driveway is allowed to remain where it is, they will not have sufficient setback to construct that garage. They thus brought the present action against the McGees, seeking the driveway's relocation to its deeded place. The Frysingers were added to the case because the driveway's relocation moves it closer to their garage and house and would require them to move various things they have placed in the affected area. [Note 1]

The McGees do not dispute that their existing driveway encroaches on the other properties, but contend that they have either an easement by implication or an easement by necessity which entitles them to leave it where it is. No easement by prescription is claimed because the driveway encroachments lack the required twenty years of adverse use, the lots having been in common ownership within that period. [Note 2]

The case was tried before me, jury-waived. Based upon the testimony and documents admitted at trial, my assessment of the credibility, weight, and inferences to be drawn in light of that evidence, and as more fully explained below, I find and rule that the McGees do not have an easement by implication or an easement by necessity for use of the encroaching portions of the driveway, and thus the encroachments must be removed. Since neither the McGees nor the Frysingers requested a declaration or other relief regarding the Frysingers' use or encroachments on the McGees' deeded driveway area, I make no such ruling, leaving that to such subsequent proceedings as those parties may bring.

Implied Easements by Necessity

The McGees allege that they possess an implied easement by necessity. Such an easement is implied when a parcel is conveyed out of land under common ownership and the land retained by the common owner would be landlocked without access over the land conveyed. Town of Bedford v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 77 (2004). Similarly, "[a] right of way of necessity over land of the grantor is implied by the law as a part of the grant when the granted premises are otherwise inaccessible, because that is presumed to be the intent of the parties. The way is created not by the necessity of the grantee but as a deduction as to the intention of the parties from the instrument of grant, the circumstances under which it was executed and all the material conditions known to the parties at the time." Orpin v. Morrison, 230 Mass. 529 , 533 (1918).

"The burden of proving the intent of the parties to create an easement which is unexpressed in terms in a deed is upon the party asserting it." Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 101 , 105 (1933). As the courts have noted, "[i]t is a strong thing to raise a presumption of a grant in addition to the premises described in the absence of anything to that effect in the express words of the deed." Orpin, 230 Mass. at 533. Thus, "[s]uch a presumption ought to be and is construed with strictness." Id. While the necessity which gives rise to the presumption need not be an absolute physical necessity, it must be a reasonable necessity. See Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. at 105. Importantly, the right to such an easement ends when the necessity no longer exists. See Hart v. Deering, 222 Mass. 407 , 414 (1916) ("where the necessity for such a way ceases, the right is at an end"); Viall v.

Carpenter, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] 126, 127 (1859) ("Assuming that the defendant once had a right of way of necessity, that right ceased when the necessity ceased by his having access to the locus over his other land"); Baker v. Crosby, 9 Gray [75 Mass.] 421, 424 (1857) (acquisition of other land, removing the necessity, ended easement by necessity); Burlingame v. Gay, 83 Mass. App. Ct. 1135 , 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 (Mass. App. Ct.) (unpublished Mem. & Order Pursuant to Rule 1:28) and cases cited therein (same).

A variant of such an easement, also argued by the McGees, is an easement by implication from preexisting use, again dependent upon necessity. As the case law describes it, "[w]here during the common ownership of a parcel of land an apparent and obvious use of one part of the parcel is made for the benefit of another part and such use is actually made up to the time of severance and is reasonably necessary for the enjoyment of the other part of the parcel, then upon severance of the ownership a grant to continue such use may rise by implication." Sorel v. Boisjolie, 330 Mass. 513 , 516 (1953). Again, the easement must be reasonably necessary. Id. And again, the right to such an easement ends when the necessity no longer exists. See Burlingame, 2013 WL 2450580 at *2 and cases cited above. "Reasonable necessity does not exist if the party claiming the easement has access to his land from another parcel." Id.

Facts

These are the facts as I find them after trial.

The Lavallee, McGee, and Frysinger properties were all once part of a single lot, with one house and its associated garage, which was acquired by Carmine Zamarro, Amerigo Zamarro, Jr., and Paul Zamarro as trustees of the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust from Frank and Gladys Kohlstrom on July 2, 1991. The Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust [Note 3] was established by the three Zamarro brothers to acquire rental properties in Massachusetts. [Note 4] Following the acquisition of the property from the Kohlstroms, the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust consulted with an engineer, James Zingarelli, and tasked him with dividing the 3.849 acre parcel into as many residential parcels as possible, while still satisfying applicable zoning requirements. This involved drawing the lot boundaries so that the existing house and its garage satisfied all setback requirements, and so that each lot had access to Bailey Road.

The plan was drawn in accordance with those instructions and, on April 23, 1992, the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust presented it to the Holden Planning Board as an Approval Not Required ("ANR") Plan, with the property now divided into three lots (Lots 1, 2, and 3). See Ex. 1 (copy of ANR plan). Lot 1 would have access directly from Bailey Road. [Note 5] Lot 2 had an existing driveway to the existing house and garage. See Trial Ex. 21N. Although Lot 3 has 188.02' of frontage on Bailey Road on its eastern side, that frontage could not be used as an access point because of wetlands issues (an abutting pond and brooks). To make Lot 3 buildable, therefore, other access was needed. The plan thus configured Lot 3 with a separate 15.33' frontage area on Bailey Road and an access strip (the "deeded driveway") from there to the back of the lot where its house would be built. See Ex. 1. The deeded driveway is angular because of the setbacks necessary for the existing house and garage, now on the separate Lot 2. See Ex. 1. The ANR Plan was endorsed by the planning board on June 17, 1992 and recorded the next day. See Ex. 1. Each of the deeds to the newly created lots references that plan and gives its bounds precisely as the plan shows.

At the time of the division, Lot 2 was the only parcel with an existing dwelling. See Ex.

1. The intent was to build a house on Lot 1 for rental purposes and a house on Lot 3 as a personal residence for Carmine and his then-wife Phyllis. On June 5, 1992, revised June 23, 1992, the Zarnarro Brothers Realty Trust submitted a Notice of Intent to the Holden Conservation Commission for the construction of dwellings on those two lots, with its associated site plan showing the proposed driveway to the house on Lot 3 located entirely within the boundaries of the deeded driveway. See Trial Ex. 5. On July 23, 1992, the Conservation Commission issued an Order of Conditions allowing the proposed construction, conditioned on the work's conformance to the site plan, including the location of the driveway. See Trial Ex. 6.

Prior to beginning construction on the two proposed houses, Lots 1 and 3 had to be cleared and the sites prepared. This was done by removing large amounts of gravel and cutting down trees. Sometime during the latter part of 1992, for the purpose of removing those trees and gravel and other site-preparation and construction activities while the lots were still in common ownership, the Zarnarro Brothers Realty Trust cut a 25' to 30'-wide pathway from Bailey Road up to Lot 3. This pathway was without the benefit of a survey or staking to locate Lot 3's boundaries.

Construction on Lot 1 began in November 1992. In May 1993, soon after that house was complete, Carmine and Phyllis moved in and construction began on the house on Lot 3.

Common ownership of the properties ceased shortly thereafter, in the following manner.

On July 12, 1993, the three trustees of the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust (Carmine, Amerigo, and Paul Zamarro) conveyed Lot 1 and Lot 2 to Carmine and Amerigo Zamarro as trustees of a new trust, the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust. Paul was neither a trustee nor a beneficiary of the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust. On the same day, the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust also conveyed Lot 3 to Carmine Zamarro and his then-wife, Phyllis, as tenants by the entirety. Carmine and Phyllis acquired title to Lot 3 for the purpose of constructing their own personal residence, not for use as another rental property. Neither Amerigo nor Paul ever held an interest in Lot 3 after the transfer to Carmine and Phyllis. Similarly, Phyllis never held an interest in Lots 1 or 2.

Construction of the dwelling on Lot 3 began in May 1993 while the lot was still owned by the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust, but was finished after common ownership of the properties ceased. Construction was complete in November of 1993, after which Carmine and Phyllis Zamarro moved out of Lot 1 into the residence on Lot 3. They then began using the former construction pathway as their access to that residence.

During the time they lived on Lot 3, Carmine and Phyllis made several changes to the pathway and the surrounding landscape, converting it into a narrower driveway for residential use. To start, in 1994, they added asphalt grindings to the narrower way. Subsequently, they cleared trees, installed boulders, planted pine trees, installed a telephone pole, installed a water line to service Lot 3, and installed cement-based light posts along the driveway. [Note 6]

On August 17, 1997, in connection with their divorce, Carmine transferred his interest in Lot 3 to his ex-wife Phyllis individually, who then conveyed the property to Robert and Debra Miller on May 28, 1999. In November of 1999, the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust conveyed Lot 1 to the Lavallees. No express easement over Lot 1 for the benefit of Lot 3 was ever granted, either in that deed or otherwise. In fact, the only easement ever granted on any of the three lots was the utility easement, burdening the Frysinger lot (Lot 2) for the benefit of the McGee property (Lot 3), referenced in n. 6 above. See Trial Ex. 14. This easement was granted on February 11, 2000. Later in 2000, after the utility easement was granted, the Millers paved the gravel driveway, solidifying the driveway in its present location.

After conveying Lot 1 to the Lavallees, only Lot 2 was ovmed by the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust. Immediately after granting the utility easement to the Millers, the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust conveyed Lot 2 to Jeffrey Frysinger, who had been renting the house from that trust since 1996. Mr. Frysinger subsequently conveyed Lot 2 to himself and his wife, Kim Frysinger, then to Kim Frysinger individually in 2009. In 2011, Kim transferred title back to Jeffery Frysinger and herself. Over the years, the Frysingers have used a portion of Lot 3's deeded driveway as a lawn area for their home, as well as for underground improvements

(septic system and utilities) to their property. In 2010, the final conveyance to the present parties occurred when the Millers deeded Lot 3 to the McGees.

From the time the house on Lot 3 was finished in November 1993 and Carmine and Phyllis moved in, the existing driveway has been used nearly daily by the residents of Lot 3 (the now-McGee property) and, at some point (the evidence did not indicate when), its front portion by the residents of Lot 2 (the now-Frysinger property) as well. During the spring of 2012, the Lavallees had their property surveyed in connection with a proposed garage and discovered that the existing driveway to Lot 3 encroached on their land and, if allowed to remain there, would prohibit the garage's construction. See Ex. 2. Up until the 2012 survey, the Lavallees, McGees, and Frysingers believed that the existing driveway to Lot 3 was entirely within the boundaries of the deeded driveway. After the McGees refused to relocate the driveway to those boundaries, the Lavallees brought this suit, filing it on June 21, 2013.

In order to relocate the driveway, the McGees would have to cut down several trees, remove part of an earthen berm, remove several boulders, cross over part of the Frysingers' septic system (assuming they allowed it to remain there), potentially relocate a telephone pole, and relocate several of the driveway lights. Once relocated within the boundaries of its deeded area, the driveway would turn at three distinct points, creating an elongated "W" shape instead of its current slight curve. See Ex. 2. Both the McGees and the Frysingers contend that relocating the driveway will make it more difficult to maintain in the winter and for larger vehicles to

access the property. [Note 7] I disagree, finding that while this may make the driveway less convenient to navigate and plow, it will not make it materially more difficult to do so, it will not create any safety or visibility issues, and the deeded driveway-placed in that location by a licensed engineer and reviewed and approved by both the Town of Holden's Planning Board and Conservation Commission-will be fully adequate for all driveway purposes.

Further facts, as pertinent to the analysis are set forth below.

Analysis

As noted above, the McGees (supported by the Frysingers) claim an easement over the encroaching areas (1) by necessity, and (2) by pre-existing use during a period of allegedly common ownership. Both claims fail. Both require "necessity", which does not exist. And the "pre-existing use" for which the claim is made (as a residential driveway) did not exist during a period of common ovmership.

I begin with "necessity." Both claims require it. See discussion at pp. 3-4 above. No such necessity exists. Lot 3 was created with a deeded driveway designed by a licensed engineer, fully familiar with the site, its features, and its topography. [Note 8] I find, as fact, that the, deeded driveway is fully adequate for access and, indeed, was reviewed and approved for that purpose by both the Town of Holden's Planning Board (the endorsed ANR plan, Ex. 1) and its Conservation Commission (Trial Exs. 5 & 6).

Moreover, as a separate and independent pre-requisite to either type of easement claimed, the land at issue (here, the land on which the encroachments exist) must have been in common ownership at the time the claimed use began and the route claimed must have been the route intended for permanent use. See Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. at 77; Sorel, 330 Mass. at 516 (1953); Orpin, 230 Mass. at 533. Although the McGees are correct that Lots 1 and 3 were held in common ownership in 1992 when a gravel access path to Lot 3 was cut (a narrower part of which was later to become the driveway presently in dispute), that path was cut for a different purpose---construction access---that was not meant to continue for permanent residential use. Put simply, had it been so intended, it would not have been cut so wide (the construction path was cut 25' - 30' wide; the deeded driveway was only 15.53' wide), a survey would have been done to ensure that it was placed within the boundaries of the deeded driveway, or an express easement would have been granted and duly reflected on the relevant deeds to reflect a permanent, residential-access status. (See the express utility easement that was granted) (Trial Ex. 14). Note also that the existing driveway was never used by the common owner (the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust) for residential purposes. The trust had conveyed Lot 3 before any such use began. Rather, the construction pathway was first used for residential purposes by the new owners of Lot 3, Carmine and Phyllis, and thereafter by Phyllis and her successors.

The McGees contest this, arguing that, despite the different names of the trusts, their different trustees, and their different beneficiaries, the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust and the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust should be viewed as one and the same for "common ownership" analysis purposes, relying on the fact that Carmine remained a part of each conveyance either individually or as trustee. This contention fails. As the evidence showed, the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust was a separate and distinct trust from the Zamarro Brothers Realty Trust, with different trustees and different beneficiaries. Paul Zamarro was neither a trustee nor a beneficiary of the Zamarro Brothers Holden Realty Trust. Moreover, neither Amerigo nor Paul Zamarro held an interest in Lot 3 after the transfer to Carmine and Phyllis Zamarro, as tenants by the entirety. Phyllis Zamarro never held an interest in Lot 1 or 2. It is clear that Lot 3 was not to be another rental property for the trust, but rather a personal residence for Carmine and Phyllis.

Even if the McGees were to provide sufficient evidence of common ownership and intent to make a portion of Lot 1 burdened by the encroachments for the benefit of Lot 3, they fail to demonstrate that crossing over Lot 1 was, and continues to be, reasonably necessary in order to gain access to Lot 3. No implied easement by necessity exists, nor an implied easement by necessity through prior use, because the easement claimed is for access, and there was never any necessity for such an easement. See Hart, 22 Mass. at 410; Viall, 14 Gray [80 Mass.] at 127; Baker, 9 Gray [75 Mass.] at 424; Sorel, 330 Mass. at 516 (1953); Burlingame , 2013 WL 2450580 at *2. There has always been sufficient access to Lot 3 from the 15.33' frontage and accompanying deeded driveway created by the engineer in the approved ANR Plan. Carmine Zamarro testified that he cut the construction path in its location because he believed it flowed better with the natural contours of the land. He also testified that he "wasn't overly concerned" with putting the path where the driveway was located on the plan. (Zamarro Testimony, 224). The fact that he preferred a different location than the one developed by the engineer does not make crossing over Lot 1 necessary to access Lot 3. The evidence showed, and so I find, that the deeded driveway is fully functional, safe, and adequate for all access purposes. It may not "flow" as easily as the existing driveway, but it is the route planned, recorded, and unambiguously reflected in each of the parties' deeds.

The relocation of the driveway to its record boundaries will provide full, safe and sufficient access to the McGee property without the need to encroach on the Lavallee property. An easement by necessity is not justified merely because the McGees and Frysingers argue that relocating the driveway, along with other features, might be expensive or burdensome. I find that it will not. Moreover, the Lavallees are themselves burdened by the present encroachment of the driveway, which prevents them from constructing their proposed garage. Although continued use of the existing driveway may be, convenient for the McGees, is not enough to imply an easement to use the driveway when a suitable alternative route, designed by an engineer and approved by the Holden Planning Board, is existing and fully available for construction and use.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find that the McGees have not acquired an easement by prescription, by implication or by necessity over the Lavallee or Frysinger properties in the locations claimed, and all such claims and potential claims are DISMISSED in their entirety, WITH PREJUDICE. It is ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that the McGees, at their own expense, remove all encroaching parts of the existing driveway from the Lavallee property, and that they restore that land to its natural state, by no later than 120 days from the date of the judgment.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

MICHAEL and MARIE-ANNE LAVALLEE v. KIERAN and LESLIE McGEE v. JEFFREY and KIM ANN FRYSINGER.

MICHAEL and MARIE-ANNE LAVALLEE v. KIERAN and LESLIE McGEE v. JEFFREY and KIM ANN FRYSINGER.