Plaintiffs/Defendants-in-Counterclaim Thomas R. Despard, Jr., and Jean Despard (Plaintiffs or Despards) initiated this action against their abutters, Defendants/Plaintiffs-in-Counterclaim Jean Fabrocini, Gail Carneiro and Lynette Zacchera (collectively, Defendants) to determine the rights of the parties in and to a portion the property owned of record by Defendants (Disputed Area). The parties' abutting properties are located within the Congamond Lakes area of Southwick. In a three-count Complaint, filed July 19, 2013, Plaintiffs allege they have a prescriptive easement over the Disputed Area pursuant to G. L. c. 187, § 2, and ask the court for a declaratory judgment pursuant to G. L. c. 23l A, § 1, that they have acquired the easement as a result of their activities on the Disputed Area between 1980 and 2000-2001. [Note 1]

Defendants filed an Answer on September 6, 2013, asserting several affirmative defenses and a three-count counterclaim. In Count I of the counterclaim, Defendants seek a declaratory judgment under G. L. c. 23 l A that their record interest is not subject to a prescriptive easement in favor of Plaintiffs. In Counts II and III, Defendants allege trespass by conduct and encroachment of structures, respectively. On April 28, 2014, Defendants filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction, seeking to enjoin and restrain Plaintiffs from using the Disputed Area. A hearing on the motion was held May 8, 2014, at which all parties were heard, and the motion was granted May 23, 2014.

A one-day trial took place on September 9, 2014. The court viewed the properties in the presence of both parties' counsel on the same date. The court heard testimony from Plaintiffs and Defendant Jean Fabrocini. Neither of Mrs. Fabrocini's daughters testified. At the close of Plaintiff's case, Defendants moved for involuntary dismissal, pursuant to Mass. R. Civ. P. 41(b)(2). That motion hereby is DENIED.

Based on the parties' stipulations, the credible testimony, and exhibits entered in evidence and the reasonable inferences drawn from this evidence, and informed by the court's observations at the view, the court finds the following facts:

The Parties

1. The Despards own and reside at 129 North Lake Avenue in Southwick (Despard Property), which is described in two instruments recorded with the Hampden Registry of Deeds in Book 17691, at Page 252 and in Book 6960, at Page 198. [Note 2] They have owned their property since 1980.

2. Defendant Jean Fabrocini (Mrs. Fabrocini) resides at an abutting property, 119 North Lake Avenue (Fabrocini Property).

3. Jean Fabrocini and her spouse, Joseph Fabrocini, (often referred to by the witnesses at trial as "Tony"), purchased the Fabrocini Property in February 1975. Joseph Fabrocini died in 2012.

4. Jean Fabrocini is a life tenant of the Fabrocini Property pursuant to a deed recorded in Book 19268, at Page 447. The remainder interests are held in common by Jean and Joseph Fabrocini's daughters, Defendants Gail Carneiro and Lynette Zacchera, through the same deed. While the three named Defendants are the current record owners of the Fabrocini Property, against whom Plaintiffs' claim must be brought, during the years relevant to this action, neither Gail Carneiro not Lyneette Zacchera had an ownership interest in the property, which was owned by their parents, Joseph and Jean Fabrocini.

5. The parties' properties are depicted on two record plans:

a. "Bungalow Heights Southwick, Mass. Owned by H.S. Rainville." It is dated April 1915 and recorded in Plan Book C, at Page 70 (1915 Plan).

b. "North Pond Terrace Southwick, Mass. Owned by William P. Marcoulier Westfield, Mass." It is dated 1923 and recorded in Plan Book O, at Page 49 (1923 Plan).

6. Plaintiffs hold record title to parcels ninety (90), ninety-one (91) and ninety-two (92), as shown on the 1923 Plan.

7. Defendants hold record title to parcels eighty-six (86), eighty-seven (87), eighty-eight (88) and eighty-nine (89), as shown on the 1923 Plan, as well as parcels seventy-seven (77), seventy-eight (78), seventy-nine (79) and eighty (80), as shown on the 1915 Plan. Parcels 78, 79, and 80 comprise the Disputed Area.

The Disputed Area

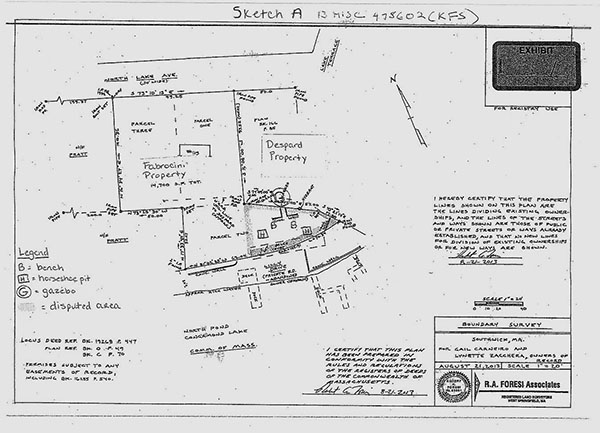

8. The Disputed Area is identified and highlighted in Plaintiffs' Trial Exhibit 1, and is depicted on Sketch A attached hereto.

9. When Plaintiffs purchased the Despard Property in 1980, they began clearing the Disputed Area of overgrown brush and trees. Their work within the Disputed Area continued during the course of several years, and over time resulted in the creation of a grassed lawn and the installation and upgrading and maintenance of two horseshoe pits, a bocce court, a wooden bench and a gazebo (which is in part within the Disputed Area.)

10. Work on the horseshoe pits occurred between 1980 and 1988. During that those years, Plaintiffs first installed rudimentary pins for catching the horseshoes. In 1981, they installed wooden boards framing the horseshoe pits. In or around 1983-1984, Plaintiffs constructed more elaborate wooden framing for the horseshoe pits, and added backstops; and in 1988, they constructed wooden framing around the horseshoe pits for a third time, replacing the original framing boards with pressure-treated wood.

11. After completing the pits, Plaintiffs started a horseshoe league, with games played once a week on Friday nights throughout the summer, utilizing much of the Disputed Area to accommodate league members during their games. The league lasted approximately ten years. Mr. Fabrocini was a member of the league for a few of the years, beginning in approximately 1986.

12. In approximately 1983, Plaintiffs installed an underground sprinkler system in the Disputed Area. In 1985 and 1987, they installed outdoor lighting to illuminate the Disputed Area at night. [Note 3] In approximately 1988, Plaintiffs constructed block walls on

the Disputed Area.

13. Also sometime in 1988, Plaintiffs constructed a bocce court within the Disputed Area. Plaintiffs also constructed and placed a wooden bench near the court around this same time. While most of the improvements to the Disputed Area were done by Plaintiffs, on two occasions Joseph Fabrocini was involved. The timing of his involvement was not established definitively at trial, but he stained the wood frames of the bocce court on one occasion and burned leaves on the bocce court on one occasion.

14. In 1994, Plaintiffs constructed their gazebo. Joseph Fabrocini lent Plaintiffs money to fund this construction, and the loan was repaid at some point.

15. Plaintiffs have maintained the Disputed Area, by performing landscaping activities such as mowing the lawn during the warm weather months. [Note 4]

16. Plaintiffs' use included playing horseshoes and bocce ball, hosting the horseshoe league weekly and approximately four substantial parties per year, one or two of which involved use of the Disputed Area, playing ball with their children, and, in the winter, occasional sledding and playing in the snow. [Note 5]

a. Plaintiffs hosted a Fourth of July party on the Disputed Area every year between 1980 and 2011. Plaintiffs sent out flyers to invited guests, which included the Fabrocinis. The Fabrocinis attended several, but not all, of Plaintiffs' Fourth of July parties. The parties and activities within the Disputed Area at the invitation and direction of the Despards could be seen and heard from the Fabrocini Property. The number of people attending each year was "about 50 to 75, possibly a hundred."

b. Plaintiffs hosted family reunions on the Disputed Area every summer beginning on or around August 1987, for approximately 15 years.

17. The Fabrocinis have a deck attached to the back of their house, from which they can observe the Disputed Area. Mr. and Mrs. Fabrocini often sat on the deck while Plaintiffs and their guests used the Disputed Area.

18. Defendants knew that the horseshoe pit, bocce court, benches, gazebo and outdoor lighting were installed by Plaintiffs in whole or in part within the Disputed Area.

19. Defendants knew Plaintiffs hosted parties and family gatherings in the Disputed Area. Plaintiffs often asked Defendants for permission for Plaintiffs' invitees to park within the Fabrocinis' driveway to accommodate the large attendance at their parties.

20. There is no evidence that Plaintiffs ever sought permission from Defendants to use the Disputed Area, nor is there evidence that Defendants expressly granted permission to Plaintiffs for such use.

21. The twenty-year time period during which Plaintiffs claim a prescriptive easement was established is 1980-2001. [Note 6]

22. In 2006, fire destroyed much of the Despards' house, which they rebuilt in an expanded form. In order to do so, they were required to upgrade their septic system, which they did by receiving from the Fabrocinis an easement to install a septic system under the Disputed Area. There was no consideration for this express easement, which was recorded on October 13, 2006.

* * * * * *

I. Plaintiffs Have Established A Prescriptive Easement Over The Disputed Property

In this case, what once appears to have been a cordial and friendly relationship between neighbors has devolved into an intractable dispute over the use of an area of land located behind both parties' homes. The record fails to fully illustrate the scope of the relationship that once existed between the parties. In their testimony, the Despards characterize their relationship with Mr. and Mrs. Fabrocini as one that was initially indistinguishable from those with other neighbors, and only developed into a friendly relationship over time. Mrs. Fabrocini describes a closer relationship that was established quickly after the Despards moved into their property. As evidence of the closeness of the relationship, Mrs. Fabrocini points to the fact that she and her husband were chosen by the Despards as godparents to Plaintiffs' youngest child, Thomas, who was born in 1991. Mrs. Fabrocini explained that she and her husband were "very close friends with Mr. Despard's mother and father" as part of her explanation of the speed and ease with which she and her husband became friendly with the Despards, coming "closer and closer together, like a family."

During his testimony, Mr. Despard explained that "Tony has grown on me a little bit as the years went on; and after my house burned down [2006] you know, like-and he gave me the easement, like that's when we really bonded." But, as Mrs. Fabrocini pointed out, years before that, in 1991, they chose the Fabrocinis to be godparents to their youngest son. Mr. Despard testified that the choice was at the request of Mr. Fabrocini. It may have been. The lack of testimony from Mr. Fabrocini leaves many questions unanswered, as it is clear from all the testimony that the strongest link among the two families was the one between Joseph Fabrocini and Thomas Despard. This court is now faced with the difficult decision of whether Plaintiffs established a prescriptive easement over the Disputed Area, given the unusual circumstances and the contradictory and often incomplete testimony, when the relationships between the parties has clearly deteriorated and neither side's testimony satisfactorily answers questions about motives

or the parties' conduct. Nonetheless, there is significant factual context established at trial from testimony and documentary evidence, including photographs, upon which this court finds that the Despards, who have the burden of persuasion, have proven that their use of the Disputed Area for certain purposes was without permission, as case law has distinguished permission from acquiescence, and their conduct otherwise satisfies the elements of prescription.

To establish a prescriptive easement, a party must prove open, notorious, adverse, and continuous or uninterrupted use of land for a period of not less than twenty years. G. L. c. 187, § 2; Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 43--44 (2007). As with an adverse possession claim, the party claiming a prescriptive easement carries the burden of proof and persuasion on each element. Ivons-Nispel, Inc. v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 762 (1964); Rottman v. White, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 586 , 589 (2009). Whether the elements of a claim for a prescriptive easement have been satisfied is a factual question. Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 363 (2009). Failure to provide sufficient evidence on any of the elements defeats the entire prescriptive easement claim. Gadreault v. Hillman, 317 Mass. 656 , 661 (1945).

a. Twenty- Year Period

Plaintiffs presented sufficient evidence at trial demonstrating they used the Disputed Area for a period in excess of the required twenty-year period. They purchased the Despard Property in 1980, and began utilizing the Disputed Area immediately. This general use, consisting of activities and improvements made to the area, continued until at least 2001, and beyond, satisfying the twenty-year period required under G. L. c. 187, § 2.

b. Continuous Use

A prescriptive easement also requires use that is continuous and uninterrupted for the twenty-year period. Seasonal use or periodic use may be deemed continuous, provided it is done consistently. Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 321 (1961); Mahoney v. Heebner, 343 Mass. 770 , 770 (1961). Upon moving into their home, Plaintiffs began clearing overgrown brush and trees from the Disputed Area to create a lawn. They laid down sod and grass, regularly mowed the lawn once it was created, and planted flowers. They constructed various structures, including a bocce court, horseshoe pits, and installed benches and a gazebo. They hosted annual parties, gatherings and events, using these structures and the Disputed Area generally. They formed a horseshoe league and hosted regular weekly games within the Disputed Area for a period of years. Although Plaintiffs admit they mainly used the Disputed Area during the summer, some less intensive and more sporadic use also extended into fall and winter when Plaintiffs raked leaves or went sledding in the Disputed Area. Many of these uses and activities occurred annually from 1980 to 2001, and constitute the continuous use required to establish a prescriptive easement.

c. Open and Notorious Use

Open and notorious use must be "without attempted concealment," White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 416 (2013), and be "sufficiently pronounced so as to be made known, directly or indirectly, to the landowner if he or she maintained a reasonable degree of supervision over the property." Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. When a landowner has actual knowledge of the adverse use of the property, this element is satisfied. White, 464 Mass. at 417.

The Disputed Area is clearly visible from the Fabrocinis' home. The windows at the back of the house overlook the Disputed Area, as does Defendants' deck, attached to the back of their home. Defendants often sat on their back deck and observed the activities taking place in the Disputed Area. Defendant Jean Fabrocini admitted that she was aware of the structures and improvements made to the Disputed Area as they were constructed, and that Plaintiffs were the parties responsible.

d. Adverse Use

The final element necessary to establish a prescriptive easement is adverse use. An unexplained use of an easement for twenty years creates a presumption of adversity. True v. Field, 269 Mass. 524 , 528-29 (1930); Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836, citing IvonsNispel, 347 Mass. at 763. The true owner can overcome the presumption by offering evidence that explains the use or shows control over the use. Id. For example, the true owner can defeat the presumption by showing there was express or implied permission or the use was the result of "some license, indulgence, or special contract." White v. Chapin, 94 Mass. 516 , 519-520 (1866).

In their post-trial brief, Defendants allege that Plaintiffs' use of the Disputed Area was not adverse because they did so with Defendants' permission. Mrs. Fabrocini characterized their relationship with Plaintiffs as one that began as neighbors, but quickly developed into a closer, familial bond. However, both Plaintiffs testified they never sought permission from Defendants before undertaking any use of the Disputed Area, nor did they receive any permission. They stated several times that they had no conversations with the Fabrocinis about their uses or improvements to the Disputed Area (other than about the gazebo, for which Mr. Fabrocini lent Mr. Despard money for construction.) On the contrary, the Despards testified that they thought the Disputed Area was part of their property.

The court credits their testimony on this point, but notes that at some point, the Despards must have determined that the Disputed Area was not owned by them as part of the Despard Property because, in 2006, in connection with the reconstruction of their fire-damaged house, Mr. Despard asked Mr. Fabrocini for an easement in order to install a new septic system underneath the Disputed Area. Mrs. Fabrocini did not counter the Despards' testimony regarding lack of permission granted to the Despards to use the Disputed Area. While Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836, instructs that a true owner can overcome the presumption of adversity of use by offering evidence that explains the use or shows control over the use, no such evidence was forthcoming at trial.

There was no testimony about conversations Mrs. Fabrocini had with her husband Tony, when he said that he had given Mr. Despard permission to makes improvements to the Disputed Area. It was clear that Plaintiffs made no attempt to hide or conceal their use of the Disputed Area, held themselves out as the people in charge of it by inviting guests to parties and hosting a horseshoe league there for many years. They acknowledge that Mr. Fabrocini on occasion would help Mr. Despard with tasks or otherwise come onto the Disputed Area, acknowledging that the Despards' use of it was not entirely exclusive. Accordingly, they have not sought, nor would the evidence have supported a claim of adverse possession to the Disputed Area. However, they have established that their use was sufficiently open and notorious for purposes of establishing their prescriptive use.

Permission, whether express or implied, defeats a claim for prescription. However, permission is not the same as acquiescence, which is not sufficient to defeat such claims. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836, citing Ivons-Nispel, 347 Mass. at 763. Permission grants an individual the right to do some act on the land. Spencer v. Rabidou, 340 Mass. 91 , 93 (1959). Whether permission has been granted or can be implied will depend on the particular circumstances of the case, including, among other relevant factors, the actions of the owner, the character of the land, the use of the land, and the nature of the relationship between the parties. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145-146 (2000); Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624-626 (1992); Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 842-843.

Defendants argue that Plaintiffs' own testimony is insufficient to demonstrate their use of the Disputed Area was adverse. However, as noted above, both Plaintiffs testified initially they thought the Disputed Area belonged to them and they never sought nor received permission from Mr. or Mrs. Fabrocini. Defendants failed to provide sufficient evidence of implied permission to rebut the presumption of adversity. Defendants argue the two families were extremely close. While the existence of a familial relationship between parties may be a factor in determining whether use is adverse, it is only one of many circumstances taken into account. Totman, 431 Mass. at 145. Defendants failed to demonstrate their actions impliedly permitted Plaintiffs' use. Defendants also failed to distinguish their actions from acquiescence. Instead, Defendants relied primarily on the fact that the parties once enjoyed a close relationship, as both neighbors and friends.

Plaintiffs' use of the Disputed Area extended beyond acts of "neighborly accommodation" by Defendants that could be construed as permissive. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 842. Plaintiffs' use of the Disputed Area reflects the type of activity one expects from people who either believe they own the property or have rights to it. The evidence established that Defendants did not exercise any control over the Disputed Area, such as by installing their own structures or improvements, or by regulating or restricting Plaintiffs' access and use. [Note 7] At most, Mr. Fabrocini assisted Plaintiffs on occasion with the construction of structures on the Disputed Area, such as the bocce court as neighbors might help neighbors who are improving their property out of a spirit of cooperation. As set forth in paragraph 14 above, in 1994, Mr. Fabrocini even lent money to the Despards so they could construct their gazebo within the Disputed Area.

It was clear to the court that for some number of years Mr. Fabrocini and Mr. Despard enjoyed a close personal relationship which they both enjoyed and which grew over time. In that context, Mr. Fabrocini's occasional assistance to Mr. Despard, including the few times Mr. Fabrocini physically helped with the improvements within the Disputed Area and the loan for the gazebo, make sense. Mr. Fabrocini's efforts were understandable in the context of the relationship between the two men. The actions of Mr. Despard were harder to understand, except within the context of his testimony that he thought the Disputed Area was owned by his wife and him. The level of activity and improvements made by the Despards to the Disputed Area from the time they purchased their property is simply hard to understand without crediting their testimony that they initially thought they owned the area. The view taken by the court of the parties' adjacent properties was instructive as the Disputed Area is located in such a way as it appears reasonable that the Despards thought the Disputed Area was part of their property.

Because Defendants failed to present evidence of permission granted to the Despards, Plaintiffs' use of the Disputed Area remains unexplained and is presumed to be adverse. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 842. Plaintiffs' use was also open, notorious, and continuous for a period greater than twenty years.

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing, this court finds that the Despards established a prescriptive easement over the Disputed Area for social and recreational use consistent with their level and type of use as set forth above. Specifically, Plaintiffs have proven the right to maintain the lawn and any plantings, including the care for the lawn and plantings necessary to keep them healthy. Plaintiffs also have established the right to maintain in good repair the structures they built within the Disputed Area, including the bocce court, the horseshoe pits, the benches, the wall and fence, and the gazebo, as well as the right to use the structures and the Disputed Area for recreational use during the summer. They have established the right to maintain the underground sprinkler system, the evidence having established that it was installed in 1983 and has been used since that time, as well as the lighting installed in the mid 1980's, but not the third fixture recently installed. They have also established a prescriptive right to host a Fourth of July party each year, but they have not established the right to invite their guests to park anywhere within the boundaries of the Fabrocini Property. They have also not established the right to host parties other than the July Fourth event, as the testimony with respect to additional parties established that their yearly August family reunion was held for only fifteen years (short of the twenty needed), and the testimony with respect to other parties was vague and unsupported. Likewise, the use of the Disputed Area for the hosting of the horseshoe league fell short of the twenty years required to establish prescriptive rights. The testimony with respect to use of the Disputed Area for playing and sledding in the winter was insufficient to support prescription. In view of the disposition of Plaintiffs' case largely in their favor, Defendants' counterclaims will be dismissed. [Note 8]

This decision and the forthcoming judgment will establish the Despards' right to continue to use the Disputed Area in common with the Fabrocinis, as set forth above. For that reason, this court would like input from counsel regarding how to fashion the terms of the judgment in order to minimize tensions which might arise if the parties are left with too little guidance as to their rights going forward. It may be, given this decision, that the parties would like time to consider its ramifications and suggest acceptable terms for the judgment. The judgment will dissolve the preliminary injunction previously issued, but until the judgment issues, the injunction remains in effect. The court will schedule a status conference and notify counsel shortly. Judgment will not issue until after that has occurred.

THOMAS R. DESPARD, JR. and JEAN DESPARD v. JEAN FABROCINI, GAIL CARNEIRO and LYNETTE ZACCHERA.

THOMAS R. DESPARD, JR. and JEAN DESPARD v. JEAN FABROCINI, GAIL CARNEIRO and LYNETTE ZACCHERA.