JOHN MASTROBATTISTA v. JONATHAN SCOTT and MICHAEL McGUILL.

JOHN MASTROBATTISTA v. JONATHAN SCOTT and MICHAEL McGUILL.

MISC 14-485877

August 6, 2015

Barnstable, ss.

LONG, J.

JOHN MASTROBATTISTA v. JONATHAN SCOTT and MICHAEL McGUILL.

JOHN MASTROBATTISTA v. JONATHAN SCOTT and MICHAEL McGUILL.

LONG, J.

Introduction

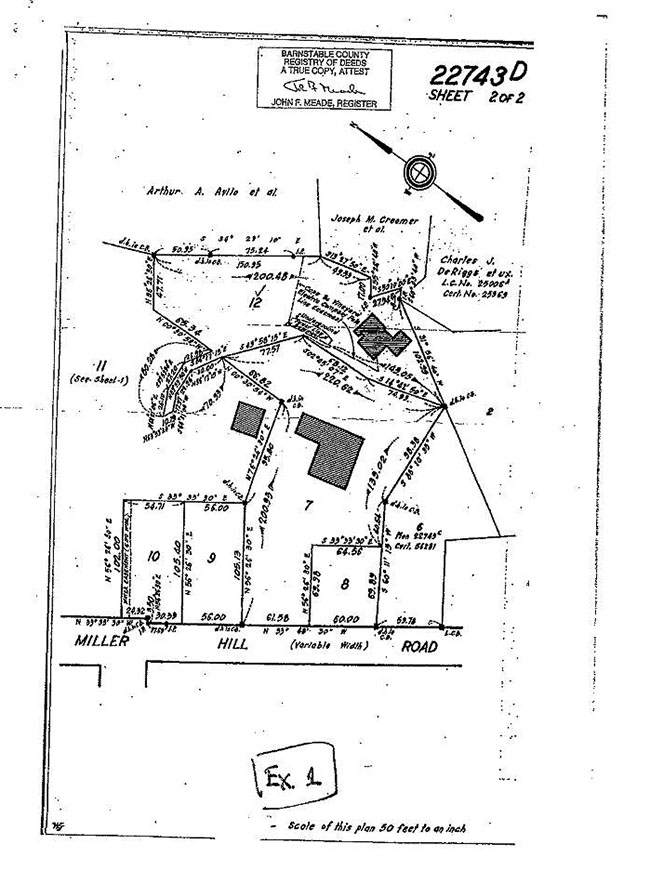

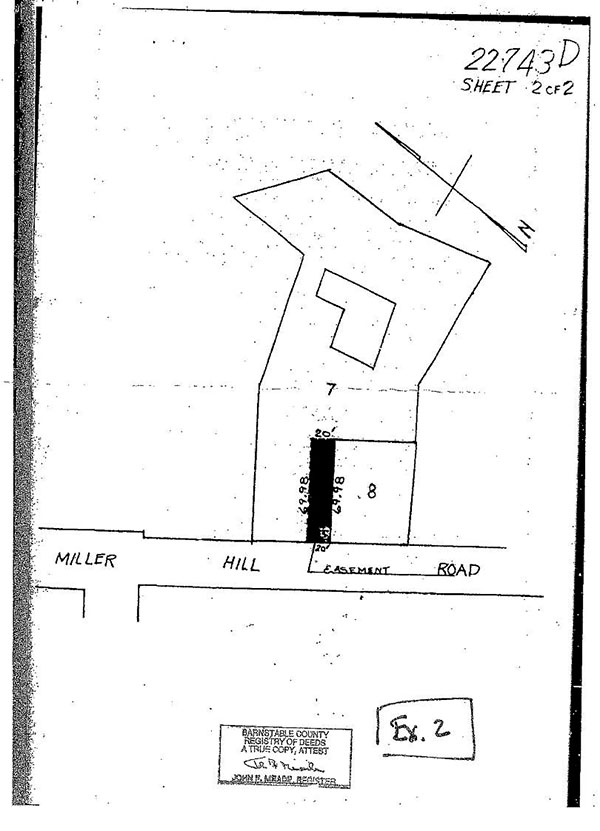

Plaintiff John Mastrobattista owns the registered land in Provincetown shown as Lot 7 on Land Court Plan 22743-D (Jul. 1972). [Note 1] See Ex. 1. The defendants, Jonathan Scott and Michael McGuill, own Lot 8. Id. There is currently a house on Lot 8 that, when originally constructed (1987), [Note 2] included a garage on its left side. [Note 3] On October 30, 1986, the then-owner of Lot 7 (Richard Barr) granted the then-owners of Lot 8 a 20- wide easement along the side of the Lot for access to gararge [sic] and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping. Easement (Oct. 30, 1986). [Note 4] The location of that easement is shown on Ex. 2.

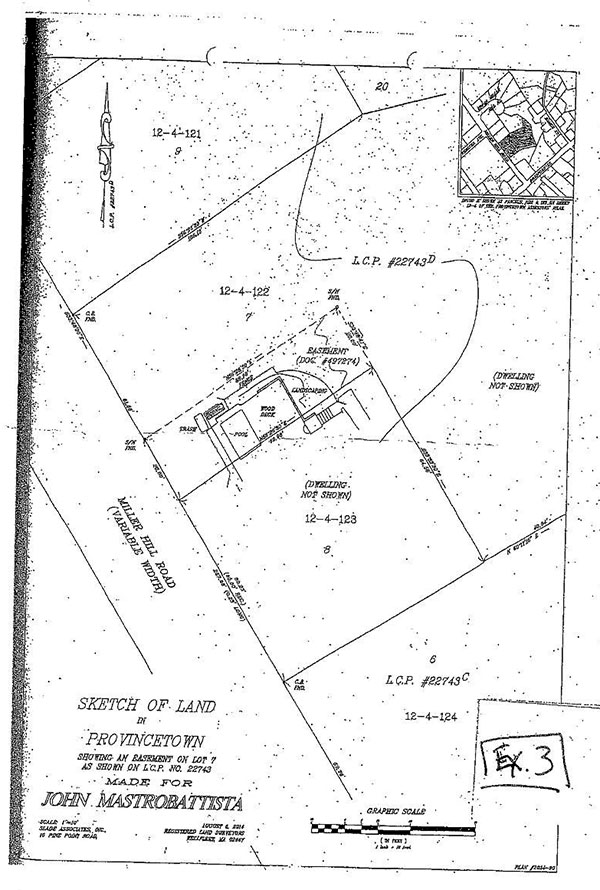

The garage has since been eliminated, with its space incorporated into the living quarters of the house. Beginning in 1990, the then-owners of Lot 8 confined their parking to the front part of the easement and, in a series of small, then larger acts, began building into the remainder of the easement area. At first (1990) they built a trash shed. Next (1991), a short fence. Some years later (1995), they constructed a small wading pool. After that it was a new (replacement) fence (2001), a well for their house (2004) and, in 2006, [Note 5] a new, high fence enclosing a much larger area and, inside that area, an expanded (8 x 12) pool surrounded by a large wooden deck with extensive outdoor furniture. [Note 6] See Ex. 3. Their driveway and parking area now end at the front fence line. Id.

Dr. Mastrobattista contends that the fence, pool, deck, concrete slab and trash shed are illegal encroachments and must be removed from his land. His land is registered, and thus neither adverse possession nor prescriptive rights can accrue against it. G.L. c. 185, §53. There are no other documents none at all in the registration system and, because none exist, no unregistered documents of which Dr. Mastrobattista has actual knowledge, see Jackson v. Knott, 418 Mass. 704 , 710-711 (1994) that contain any relevant use or occupational rights. Thus, as discussed more fully below, these encroachments can only remain if they fall within the 1986/1989 easement grant.

The defendants contend that the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed are landscaping within the scope of that grant and thus may stay. Dr. Mastrobattista disagrees, contending that the landscaping within the scope of the grant relates only to landscaping associated with a driveway and parking area, and the fence, the pool, the deck, the trash shed and the concrete slab fall outside that scope. He has thus moved for summary judgment directing their removal.

As discussed more fully below, the interpretation of the easement is a matter of law for this court, governed by the language of the grant and, to the extent that language is ambiguous, as aided by the attendant circumstances at the time of the grant. Both lead to only one conclusion. On the undisputed facts, as a matter of law, the landscaping contemplated by the grant was limited solely to landscaping related to a driveway and parking area. Dr. Mastrobattistas motion for summary judgment is thus ALLOWED, and the defendants are ORDERED to remove all portions of the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab, the trash shed, and their associated equipment, accessories and furniture that encroach into the easement area, in their entirety, by no later than 120 days from today. [Note 7]

Facts

Summary judgment may be entered when the facts material to the claims at issue are not in genuine dispute and the moving party is entitled to judgment on those claims as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c); Ng Bros. Constr. v. Cranney, 436 Mass. 638 , 643-644 (2002). Except as otherwise noted, the following facts are not genuinely in dispute.

Both Lot 7 (Dr. Mastrobattistas land) and Lot 8 (the defendants) are registered land, subdivided from a larger parcel in July 1972 by Land Court Plan 22743-D. (Ex. 1). They stayed in common ownership until October 2, 1972, when the then-owners of the two lots conveyed Lot 7 to Dr. Mastrobattistas predecessor, Richard Barr, retaining Lot 8. Some thirteen years later, on September 20, 1985, Lot 8 was conveyed to William Whitney and Charles Dudley.

The easement at issue was first granted on October 30, 1986. Only nominal consideration ($1) was paid. Mr. Barr (the then-owner of Lot 7) was the grantor. Mr. Whitney and Mr. Dudley (the then-owners of Lot 8) were the grantees. The house on Lot 8 was either in the design or early construction stages (according to the tax assessors records, it was completed in 1987), and was to have a garage on its left (northerly) side. The easement twenty feet wide ran from Miller Hill Road along the garage side of Lot 8 (see Ex. 2) and, according to the language of the grant, was for access to gararge [sic] and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping. Easement, Barr to Whitney/Dudley (Oct. 30, 1986)

Mr. Whitney and Mr. Dudley subsequently conveyed Lot 8 to Mr. Dudley alone on June 15, 1987 and, two and one-half years later, in December 1989, Mr. Dudley sold it to Gregg and Kenneth Russo. The easement was re-granted at that time in identical language with only three exceptions, none material. The grantor (Mr. Barr) was the same, but (1) the grantees were now the Russos, (2) the mis-spelling gararge was corrected to garage, and (3) the easement made explicit that it was appurtenant to Lot 8. In relevant part it continued to state, [t]he easement herein granted shall be for access to garage and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping. Easement, Barr to Russo/Russo (Dec. 12, 1989). Again, only nominal consideration ($1) was paid for the grant. The Dudley to Russo deed and the easement grant were registered with the Land Court on December 18, 1989. No amendment or supplementation of the easement has been registered with the Land Court since that time, and there are no other easements or documents giving Lot 8 any rights in any portion of Lot 7.

In his affidavit, Mr. Barr states that he granted the easement so that the 7 Miller Hill Road [Lot 8] owners could use a small section of my land for a driveway; that is, I granted the easement so that the owners could drive from Miller Hill Road to their garage on that side of the house, so that they could park there, and so that they could walk to and from their vehicles. I also allowed them to landscape so that, after the driveway work was done, they could plant around it, maintain it, and keep it looking nice. I did not intend to grant anything more. Barr Aff. at 1, ¶¶ 3-6 (Mar. 14, 2015). Mr. Barr appears to have expressed this intent solely in the language of the easement. He does not claim to have had any conversations or other communications regarding the easement with either Mr. Whitney or Mr. Dudley (the 1987 grantees) or the Russos (the 1989 grantees).

In his affidavit, Gregg Russo confirms this, stating [a]t no time prior to, or after, execution and recording of the easement, did I or by [sic, my] brother Kenneth Russo, have any discussions with Mr. Barr concerning limitations on the landscaping allowed by the terms of the easement. Russo Aff. at 2, ¶5 (Apr. 29, 2015). I thus conclude that there were no substantive communications between the grantor (Mr. Barr) and the 1989 grantees (the Russos) on the meaning of landscaping in the grant, other than the easement itself. Mr. Russos distinct understanding that there were no limitations on landscaping permitted in the easement area (Russo Aff. at 2, ¶5) thus has no basis in anything Mr. Barr said or communicated other than the language of the easement, the interpretation of which is a matter of law for this court.

As noted above, the garage on the easement side of the Lot 8 house has since been eliminated, with its space incorporated into the living quarters of the house. Beginning in 1990, the then-owners of Lot 8 confined their parking to the front part of the easement and, in a series of small, then larger acts, began building into the remainder of the easement area. At first (1990) they built a trash shed. Next (1991), a short fence. Some years later (1995), they constructed a small wading pool. After that it was a new (replacement) fence (2001), a well for their house (2004), a concrete slab just behind the trash shed (date of construction unknown) and, in either 2006 or 2011, [Note 8] a new, high fence enclosing a much larger area and, inside that area, an expanded (8 x 12) pool surrounded by a large wooden deck with extensive outdoor furniture. See Ex. 3. Their driveway and parking area now end at the front fence line. Id.

Mr. Russo claims that Mr. Barr was aware of each of these structures and never raised any objections, even complimenting him on some of them. Russo Aff. at 2-5, ¶¶7-14. In response, Mr. Barr states that (1) he was asked from time to grant another easement for the items built in the easement area, (2) [a]t no time was a pool or any other use contemplated or included in the easement and I have consistently refused to grant an easement for the pool and related construction when sought by the owners of 7 Miller Hill Road, and (3) [b]ecause the land involved is land courted, I have always been confident that the land involved cannot be claimed by the owners of 7 Miller Hill Road at any time. Barr Aff. at 1-2, ¶¶7-9 and Ex. B (Mar. 14, 2015)

In January 2013, Mr. Scott and Mr. McGuill acquired Lot 8, including the benefit of the easement in dispute. Later that same year, Dr. Mastrobattista acquired Lots 6, 7, and 20 and contacted Mr. Scott and Mr. McGuill about the encroachments. Mr. Scott and Mr. McGuill refused to remove them, and this action followed.

Analysis

Easements on Registered Land

The party asserting an easement has the burden of proving its nature and extent. Foley v. McGonigle, 3 Mass. App. Ct. 746 , 746 (1975). In order to affect registered land as the servient estate, an easement must appear on the certificate of title. Tetrault v. Bruscoe, 398 Mass. 454 , 461 (1986). There are only two exceptions:

If an easement is not expressly described on a certificate of title, an owner, in limited situations, might take his property subject to an easement at the time of purchase: (1) if there were facts described on his certificate of title which would prompt a reasonable purchaser to investigate further other certificates of title, documents, or plans in the registry system; or (2) if the purchaser has actual knowledge of a prior unregistered interest.

Jackson v. Knott, 418 Mass. 704 , 710-711 (1994). An easement on registered land cannot be acquired by adverse possession. G.L. c. 185, § 53.

The first exception does not apply. The parties agree that the easement was granted and registered with the Land Court on November 12, 1986; re-granted and re-registered in identical language on December 18, 1989; and has not been amended or supplemented since that time. There is nothing in the registration system that points to any unregistered easement on the plaintiffs land.

The second exception also does not apply. It allows for enforcement of an unregistered easement when a purchaser possesses actual knowledge of the unregistered interest. [Note 9] See Commonwealth Elec. Co. v. MacCardell, 450 Mass. 48 , 51 (2007). But the unregistered interest must be a document, meeting all the usual requirements. See G.L. c. 183, §§1, 3; G.L. c. 259, §1. [I]t is insufficient merely to claim that the holder of registered title knew that the land was being used in a way that might indicate an easement. The use may be adverse, which does not create an easement under G.L. c. 185, §53, or a registered owner might have granted permissive use. Id. at 53-54 (noting that mere knowledge of the existence of utility poles and the provision of electrical service on the servient land was insufficient to create an easement). The defendants do not claim that Dr. Mastrobattista had knowledge of an unregistered easement document giving them rights to use his land. In fact, other than the 1986/1989 easements at issue, they concede that there is no such document. Rather, they allege he had actual knowledge of the encroachments themselves the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed at the time of his purchase. True enough. But as noted above, as a matter of law, this is insufficient to create an easement on registered land. MacCardell, 450 Mass. at 53-54.

The Proper Interpretation of the 1986/1989 Easement

The case thus turns on the proper interpretation of the 1986/1989 easement grant. Easement interpretation may be decided definitively on summary judgment, as it is an issue that is purely a question of law. World Species List v. Reading, 75 Mass. App. Ct. 302 , 305 (2009), quoting McGregor v. Allamerica Ins. Co., 449 Mass. 400 , 402 (2007).

The basic principle governing the interpretation of deeds is that their meaning, derived from the presumed intent of the grantor, is to be ascertained from the words used in the written instrument, construed when necessary in the light of the attendant circumstances. Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007) (citation omitted). These same considerations govern interpretation of an easement created by deed. Id. The language establishing an easement by grant controls interpretation when it is clear and explicit, and without ambiguity. Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 25 (2006), quoting Cook v. Babcock, 61 Mass. 526 , 528 (1851). When the grants language is ambiguous, the attendant circumstances existing at the time of its creation may be used to discern the grantors intent. See Lowell v. Piper, 31 Mass. App. Ct. 225 , 230 (1991). However, a term is ambiguous only if it is susceptible of more than one meaning and if reasonably intelligent persons would differ over the proper meaning. Suffolk Construction Co. v. Ill. Union Ins. Co., 80 Mass. App. Ct. 90 , 94 (2011). The determination of whether an ambiguity exists is a question of law for the court. Id. Ultimately, [r]estrictions on land are disfavored, and doubts concerning the rights of use of an easement are to be resolved in favor of freedom of land from servitude. Martin v. Simmons Props. LLC, 467 Mass. 1 , 9 (2014) (internal quotations and citations omitted); see also St. Botolph Club Inc. v. Brookline Trust Co., 292 Mass. 430 , 433 (1935) (Doubtful cases, where the words, considered in the light of the circumstances, remain ambiguous, are resolved in favor of the freedom of land from servitude.).

The 1986/1989 easement, in relevant part, states: [t]he easement herein granted shall be for access to garage and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping. The meanings of the terms access, passage, parking, and maintaining a driveway and parking area are unambiguous and not in dispute. Since the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed do not facilitate access, passage, parking, or the maintenance of a driveway and parking area (indeed, as physical barriers, they are each inconsistent with those things), they must fall within the scope and meaning of the term landscaping as used in the 1986/1989 grant in order to remain.

I begin with the plain and ordinary meaning of the language of the instrument. The dictionary definition of a term is normally strong evidence of its common meaning. Brigade Leveraged Capital Structures Fund Ltd. v. PIMCO Income Strategy Fund, 466 Mass. 368 , 374 (2013). The dictionary definition of landscap[ing] is improv[ing] the aesthetic appearance of (a piece of land) by changing its contours, planting trees and shrubs, etc. Oxford Concise Dictionary at 798 (10th ed. 1999). The fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed were not built for aesthetic appearance. Instead, they are structures built for specific uses. They thus fall outside the easements landscaping rights.

This is made even clearer by application of the doctrine of ejusdem generis the principle of construction that, when a term is contained in series or list, specific words . . . identify the class and [restrict] the meaning of general words to things within the class. Commonwealth v. Mogelinski, 466 Mass. 627 , 639 (2013), quoting Commonwealth v. Zubiel, 456 Mass. 27 , 31 (2010); see also Patterson, 448 Mass. at 665 (When created by conveyance, the grant or reservation must be construed with reference to all its terms.) (emphasis added, internal quotations omitted). Here, the grant conveys an easement for five interrelated uses: access, passage, parking, maintenance of a driveway and parking area, and landscaping. Landscaping (a general term) must thus be read in light of these other specified uses. All must be consistent with access, passage, and parking. The fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed are clearly inconsistent with access or passage of pedestrians or vehicles or the parking of cars and thus beyond the rights granted by the easement.

Further, the servient land owner is entitled to use his land in a manner consistent with the easement. Commercial Wharf East Condominium Assn v. Waterfront Parking Corp., 407 Mass. 123 , 134 (1990). As the defendants own submissions concede, the easement area contained the path utilized by Richard Barr and Charles F. Dudley from 9 Miller Road [the house on Lot 7] to Miller Hill Road. This was the sole means of pedestrian access from 9 Miller Hill Road to Miller Hill Road and was traversed frequently by Barr and Dudley. Russo Aff. at 4, ¶13. The defendants encroachments in the easement the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed all block Dr. Mastrobattistas passage or access across that portion of his land, and for that reason as well are beyond the scope of the easement.

The defendants offered an affidavit from Horace Aikman, a landscape architect, contending that the fence, the pool, the deck, the concrete slab and the trash shed are all landscaping and thus within the scope of the easement. But this is incorrect. He made no attempt to tie the word landscaping into the rest of the easement language, viewing it instead entirely in isolation as a separate and independent grant. Moreover, in his view, pretty much anything constructed outside a house is landscaping, including small buildings. [Note 10] This is certainly not correct in the context of this easement. It ignores the rest of the easement language (for access to garage and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area) indeed, it makes it redundant and would effectively grant a fee interest.

I thus strike that affidavit as without proper foundation and, more to the point, irrelevant. I also strike those portions of the parties other affidavits (the plaintiffs and the defendants alike) insofar as they address what they understood the easement to mean. They too are irrelevant. [Note 11] The mere existence of a disputed interpretation by the parties does not create an ambiguity. Suffolk Construction Co., 80 Mass. App. Ct. at 94. If the language is free of ambiguity, our responsibility is to apply its clear terms. Id. There is no ambiguity here. The plain language of the grant and the doctrine of ejusdem generis lead to only one conclusion: the landscaping within the scope of the easement is landscaping consistent with access, passage and parking. It does not include fences, pools, decks, concrete slabs or trash sheds that block such use.

Even if the meaning of landscaping is considered sufficiently ambiguous to merit consideration of attendant circumstances, those circumstances the ones that existed at the time of the grant further support a meaning consistent with access, passage and parking. At the time of Mr. Barrs grant, with the sole exception of a small timber retaining wall towards the back, the easement area was open land running alongside Lot 8 leading to its garage. Viewed in this context, the limited intent of the grant for access to garage and building facilities on Lot 8 and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping is obvious.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I find and rule that the defendants have no right to maintain (1) the fence, (2) the pool, (3) the deck, (4) the concrete slab, (5) the trash shed, or (6) their associated equipment, accessories and furniture in the easement area, and accordingly ORDER the removal of all portions of them that encroach into that area, in their entirety, no later than 120 days from today.

Judgment shall enter accordingly.

SO ORDERED.

exhibit 1

exhibit 2

exhibit 3

FOOTNOTES

[Note 1] He is also the owner of Lots 6 and 20. Lot 20 is the southeastern portion of the former Lot 11. See Exs. 1 & 3.

[Note 2] See Town of Provincetowns Tax Assessors Card, reflecting that the house was first built in 1987.

[Note 3] See Aff. of Richard Barr at 1, ¶ 4 (Mar. 14, 2015).

[Note 4] The easement was granted again by instrument dated November 17, 1989. The only differences between the two instruments are: (1) the named grantees (Charles Dudley and William Whitney in 1986; Gregg Russo and Kenneth Russo in 1989 the grantor, Richard Barr, was the same), (2) a correction to the spelling of the word garage, and (3) the addition of a sentence making explicit that the easement was appurtenant to Lot 8. The purpose language remained precisely the same for access to garage and building facilities on Lot 8 as shown on plan 22743-D (sheet 2) and for passage of vehicles and pedestrians, the parking of vehicles of the grantees and their invitees, maintaining a driveway and parking area and for landscaping. Easement (Nov. 17, 1989).

The summary judgment record contains no evidence of anything in the easement area at the time of the original (Oct. 1986) grant, so presumably it was vacant, unimproved land. According to the record, by the time of the November 1989 re-grant, all that had been put there was a driveway and parking area and a small timber retaining wall towards the back of the easement, presumably at the rear of the area used for parking See Aff. of Gregg Russo at 2, ¶6 (Apr. 29, 2015).

[Note 5] The defendants affidavits claim that the expanded fence and deck were constructed in 2006. The tax assessors card indicates that the 8 x 12 pool was constructed in 2011, which presumably included the deck work as well (it surrounds the pool). In any event, the difference is not material to the outcome of this case.

[Note 6] A concrete slab just behind the trash shed may date from this time as well. Again, its date is not material.

[Note 7] Dr. Mastrobattista has not asked that the well be removed, and I thus do not order its removal.

[Note 8] See n. 5, supra.

[Note 9] To meet the requirement of actual knowledge, a purchaser must have some intelligible oral or written information that indicates the existence of an encumbrance or prior unregistered interest. Commonwealth Elec. Co. v. MacCardell, 450 Mass. 48 , 54 (2007).

[Note 10] According to Mr. Aikman, the fence creates a privacy screen and the pool and deck are for lounging. He does not contend that they relate in any way to access, passage or parking.

[Note 11] I do not strike those portions that address the parties communications in connection with the easement at the time of its granting (here, a negative: as the parties concede, other than the easement itself, there were none) or their observations of what existed on the ground at the time of the easement grants. These fall within attendant circumstances.