Introduction

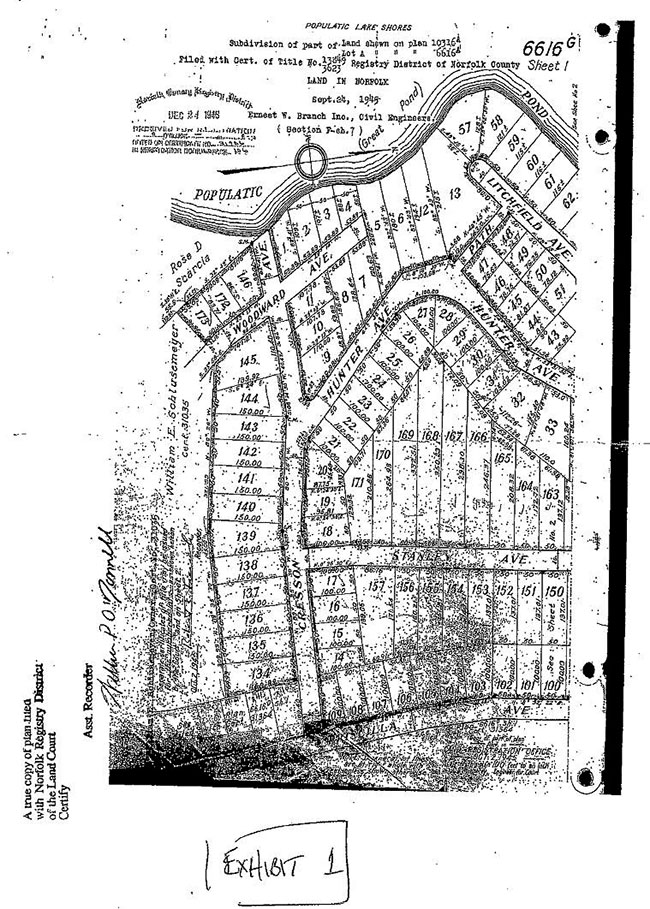

Plaintiff Mildred Kneer and her daughter Deirdre Mead, as trustees of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, are the record owners of the vacant registered land in the Town of Norfolk shown as Lots 46 and 47 on Land Court Plan 6616G, filed at the Registry on December 24, 1945. [Note 1] Norfolk first adopted zoning on March 16, 1953 and, from that time to the present, those lots, even in combination, have failed to satisfy the minimum lot size requirement. Together, they total 7650 square feet. The 1953 bylaw required a minimum of 15,000, and the current bylaw requires 43,560.

Contending that Lots 46 and 47 are grandfathered, at least in combination, Ms. Kneer, on behalf of the Trust, applied for a building permit to construct a single family home on those lots. [Note 2] By decision dated April 8, 2014, the Norfolk Building Inspector denied that application. The basis for that denial, discussed more fully below, was his determination that, for zoning purposes, those lots had previously merged with other abutting lots, thus losing whatever grandfather protection they may have had as a separately buildable lot. [Note 3] The denial was upheld by the defendant Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals by decision dated August 20, 2014, and Ms. Kneer, in her capacity as co-trustee, then timely filed this G.L. c. 40A, § 17 appeal. Mr. Murray, the abutting landowner, was allowed to intervene as an additional defendant to oppose Ms. Kneers appeal. [Note 4]

This case is thus about merger. The applicable law is well settled. [A]djacent lots in common ownership will normally be treated as a single lot [i.e. merged] for zoning purposes so as to minimize nonconformities. Carabetta v. Bd. of Appeals of Truro, 73 Mass. App. Ct. 266 , 268 (2008) (internal citations and quotations omitted). [Note 5] Merger thus takes place, as a matter of law, as soon as lots come into common ownership. Such common ownership occurs not only when the properties are titled in the same name, but also when they come within common control when the landowner has it within his power, i.e. within his legal control, to use the adjoining land so as to avoid or reduce the nonconformity[.] Planning Bd. of Norwell v. Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. 689 , 691 (1989), affd. 406 Mass. 1008 (1990). Moreover, once merged, the land cannot thereafter be un-merged. A person owning adjoining record lots may not artificially divide them so as to restore old record boundaries to obtain a grandfather nonconforming exemption; to preserve the exemption the lots must retain a separate identity. Asack v. Bd. of Appeals of Westwood, 47 Mass. App. Ct. 733 , 736 (1999), citing Lindsay v. Bd. of Appeals of Milton, 362 Mass. 126 , 132 (1972). See also G.L. c. 40A, §6.

There is an exception to this. A municipality may adopt a more liberal grandfather provision in its zoning ordinance or bylaw, preserving lots from merger in particular situations. But it must do so with clear language. Carabetta, 73 Mass. App. Ct. at 269 (internal citation omitted).

The parties agree that Lots 46 and 47 have merged for zoning purposes since both are currently titled in the names of Mildred Kneer and Deirdre Mead as trustees of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust. Where the parties differ is (1) whether those lots merged with adjacent Lots 48 and 49 at the time the 1953 zoning bylaws were enacted (all four were then in common ownership) or, instead, were grandfathered from merger at that time by the language of the bylaw (a question of bylaw interpretation), and (2) even if they were grandfathered in 1953, whether they subsequently merged with adjacent Lots 44 and 45 in 2012 because of effective common control of those properties (a question of fact). See Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 690-691.

The parties cross-moved for summary judgment on these questions. As more fully set forth below, I allow Ms. Kneers motion, and deny the defendants cross-motion, on the issue of whether the 1953 bylaw grandfathered the lots shown on the plan (Ex. 1) as they existed at that time, ruling that it did. I deny the summary judgment motions in all other respects, ruling that whether Lots 46 and 47 subsequently lost that grandfather protection a question dependent on whether those lots came into common control with Lots 44 and 45 in 2012 and thus merged for zoning purposes at that time presents a genuine issue of material fact which requires trial to resolve.

Discussion

Summary judgment may be entered if, but only if, there are no genuine issues of material fact on the claims put in issue by the motion and, based on those undisputed facts, judgment, either for or against the moving party, may be entered as a matter of law. Mass. R. Civ. P. 56 (c). Importantly, in reviewing the evidence submitted in connection with the motion, the court must draw all logically permissible inferences in favor of the opposing party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991).

In this case, as noted above, the inquiry breaks into two parts. The parties agree that Lots 46 and 47 were in common ownership with contiguous Lots 48 and 49 at the time Norfolk first adopted zoning (March 16, 1953) [Note 6] and that, because Lots 46 and 47, even in combination, lacked sufficient square footage to be separately buildable, they would have merged for zoning purposes with those commonly-owned contiguous lots unless their buildability was grandfathered by the 1953 bylaw. I thus begin with that question.

The relevant provision from the 1953 bylaw is Section 8, which states:

AREA REGULATIONS

In residential districts as provided in Section 3.1 and laid out after the adoption of this By-Law shall provide for each dwelling a minimum frontage of one hundred feet and a minimum lot area of fifteen thousand square feet. [Note 7] Lots shown on any plan duly recorded by deed or plan at the time this By-Law is adopted may be used.

Revised Zoning By-Laws of the Town of Norfolk at 6, § 8 (March 16, 1953) (hereafter, the 1953 Bylaw) (emphasis added).

The 1953 Bylaw defined lot as a parcel of land occupied or amended [sic, intended] to be occupied by one building or use, with its accessories, and including the open spaces accessory to it, which is defined in deed or plan recorded with Norfolk Deeds or Registered with the Norfolk Registry District. 1953 Bylaw, §1.A. It is undisputed that Lots 46 and 47 were shown on Land Court Plan 6616G (Ex. 1), that they were intended to be occupied by single family residences, and that Land Court Plan 6616G was filed at the Registry on December 24, 1945.

In its decision denying the plaintiffs building permit application, the Zoning Board focused on the first sentence of §8, ruling that it reflected an intent to reduce the number of small lots, and then, turning to the second sentence, that it did not clearly state an intent to allow otherwise undersized lots to be protected. Notice of Decision, Town of Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, Case #2014-05 at 12 (Sep. 3, 2014). The plaintiff disagrees, contending that the language, Lots shown on any plan duly recorded by deed or plan at the time this By-Law is adopted may be used, is an unambiguously clear expression of intent to protect the buildability of such lots, regardless of whether they have the frontage and lot area set forth in the first sentence. I agree with the plaintiff.

In the setting of a G.L. c. 40A, §17 appeal, a court owes deference to the interpretation of a zoning by-law by local officials only when that interpretation is reasonable. Pelullo v. Natick Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 86 Mass. App. Ct. 908 , 909 (2014) (rescript). An incorrect interpretation

is not entitled to deference. Shirley Wayside Ltd Pship v. Bd. of Appeals of Shirley, 461 Mass. 469 , 475 (2012), quoting Atlanticare Med. Ctr. v. Commr of the Div. of Med. Assistance, 439 Mass. 1 , 6 (2003). The meaning of a bylaw is determined by the ordinary principles of statutory construction. Shirley Wayside, 461 Mass. at 477. We first look to the statutory language as the principal source of insight into legislative intent. When the meaning of the language is plain and unambiguous, we enforce the statute according to its plain wording unless a literal construction would yield an absurd or unworkable result. Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted). Importantly, [w]e endeavor to interpret a statute to give effect to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous. Id. (internal citations and quotations omitted).

Applying these principles to §8 is simple and straightforward. Reading its two sentences together, the first sets out new frontage and lot area requirements (100 feet of frontage; 15,000 square feet of lot area), and the second in plain, direct language excepts lots shown on previously recorded plans from those requirements (Lots shown on any plan duly recorded by deed or plan at the time this By-Law is adopted may be used. [Note 8] ) (emphasis added). The Boards interpretation makes the second sentence

superfluous, and is thus incorrect. There is nothing absurd or unworkable in this literal construction. The lots protected are easily determined (they must appear on already recorded plans), and an intent to protect such pre-recorded lots, done in reliance on former law, is not absurd. §8 thus clearly and unambiguously gave grandfather protection to Lots 46, 47, 48 and 49 from the frontage and lot area requirements of the bylaw, preserving their separate buildability at that time.

Their separate buildability subsequently ceased, however, when the zoning bylaw changed. Recall that the protection from merger derived solely from the 1953 bylaw. That language changed in May 2013. [Note 9] Instead of stating that Lots shown on any plan duly recorded by deed or plan at the time this By-Law is adopted may be used, (the language in the 1953 Bylaw), it now provided that (1) no BUILDING or STRUCTURE hereafter erected in any district shall be built, located or enlarged on any LOT which does not conform to the minimum requirements of this bylaw [Note 10] (in relevant part, a minimum lot size of 43,560 square feet), [Note 11] (2) whenever the regulations made under the authority hereof differ from those prescribed by any law, statute, ordinance, bylaw or other regulations, that provision which imposes the greater restriction or the higher standard shall govern, [Note 12] and (3) a LOT or parcel of land in a residential district having an area or width less than that required by this Section may be developed for single residential use provided that such LOT or parcel complies with the specific exemptions of Section 6 of Chapter 40A of the General Laws. [Note 13] G.L. c. 40A, §6 does not give any grandfather protection from merger, [Note 14] and thus neither does the 2013 Bylaw.

Lots 46 and 47, both in common ownership, are thus now merged into a single lot for zoning purposes. The original developer, Mr. Schlusemeyer, conveyed them to Walter and Katherine Campbell on February 19, 1954 and, after several intermediary conveyances, they were conveyed to Ms. Kneer and Ms. Mead as trustees of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust on October 1, 2012, where their title remains today.

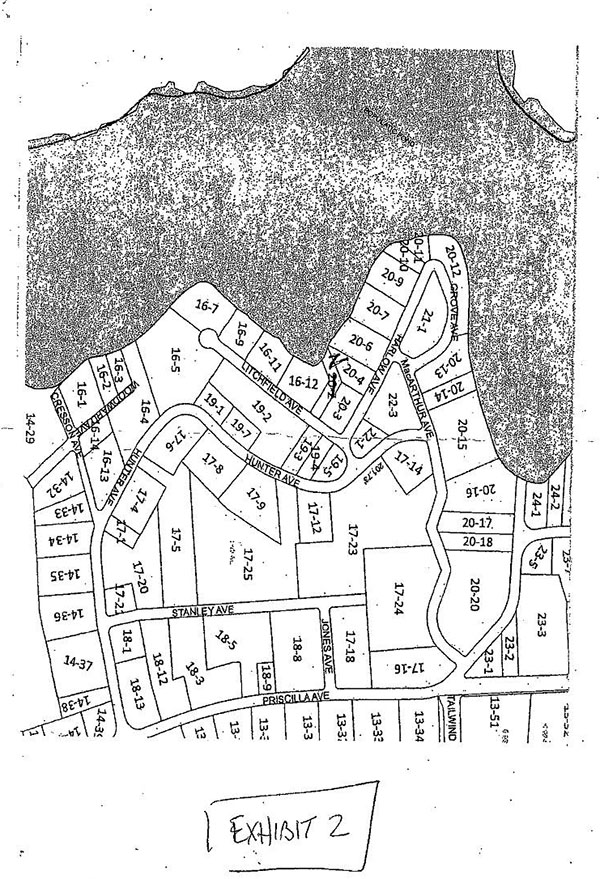

The question now becomes whether Lots 46 and 47 have merged with any of their contiguous Lots, making them unbuildable by themselves. The parties agree that this turns on whether they merged with adjacent Lots 44 and 45 in 2012 when Ms. Mead an owner (as trustee) of Lots 46 and 47 acquired title to Lots 44 and 45 in her individual name. [Note 15] The Zoning Board and the Intervenor-Defendant Mr. Murray claim that they merged because Ms. Mead obtained effective common control of all four Lots at that time. See Serena, 27 Mass. App. Ct. at 690-691.

The plaintiffs disagree, contending that both record title and control of the two sets of Lots (Lots 46 and 47 on the one hand, and Lots 44 and 45 on the other) have remained separate.

The crux of the common ownership question is not the form of ownership, but control: did the landowner have it within his power, i.e., within his legal control, to use the adjoining land so as to avoid or reduce the nonconformity? Id. at 691 (affirming the merger of one lot, held by the Serenas as tenants by the entirety, with another lot, held by a trust of which the Serenas were the trustees and sole beneficiaries), affd, 406 Mass. 1008 (1990). [A] landowner will not be permitted to create a dimensional nonconformity if he could have used his adjoining land to avoid or diminish the nonconformity. Id. at 690.

The defendants argue that Ms. Meads position as trustee of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust amounts to control sufficient to effect the merger of Lots 46 and 47 with Lots 44 and 45 when the Trust acquired Lots 46 and 47 in 2012. The plaintiff argues otherwise, contending that Ms. Mead has no authority to sell or otherwise convey Lots 46 and 47 without Ms. Kneers consent. More specifically, Ms. Kneer asserts that she is the sole beneficiary of the Trust, and distinguishes Serena on those grounds. In addition, through the affidavit of Timothy Borchers (who states that he drafted the Trust documents), Ms. Kneer contends that the Trust was created purely for estate planning purposes, that Ms. Meads status as co-trustee is merely for convenience, and that [i]f Ms. Mead were to take any action on her own, Ms. Kneer could undo that action. Affidavit of Timothy B. Borchers, Esq., in Support of Plaintiffs Motion for Summary Judgment at 2 (Jan. 29, 2015). Mr. Borchers affidavit also offers his opinions that Ms. Mead could never deed the Revocable Trust property to herself under its present terms, id., and that Ms. Mead cannot act unilaterally to bind the trust. Id. at 3. Some of this is admissible. Most is not. Mr. Borchers is competent to testify to the factual circumstances surrounding the drafting of the Trust insofar as he has personal knowledge of them (by submitting his affidavit on this topic, I assume that the trustees have waived the attorney-client privilege regarding relevant communications), but nothing more. The defendants have not yet had the opportunity to cross-examine him on those circumstances. His legal conclusions regarding the proper interpretation of the Trust provisions are stricken since they are questions solely for this court after consideration of all relevant evidence.

No discovery has taken place. None of the relevant witnesses have been cross- examined under oath. And, standing alone, none of the documents before me are definitive on the issue of control. No schedule of beneficiaries is on public file. I do not even have a complete copy of the Trust document itself, only excerpts. Despite the plaintiffs assertion that control lies solely in Ms. Kneer, the Certificate of Trust that is on public file indicates that [t]he trustees, pursuant to the provision of said trust, have authority to act with respect to the real estate owned by such trust by the execution of any one trustee acting alone. The Certificate also states that the trustees have the authority to sell the real estate of the trust and to convey trust assets to themselves either individually or as principal or trustee of another entity. Id. The Trust document itself provides that My Trustee may sell at public or private sale, convey, purchase, exchange, lease for any period, mortgage, manage, alter, improve, and in general deal in and with real property in such manner and on such terms and conditions as my Trustee deems appropriate. Thus, whether Ms. Mead should convey the property on her own without first checking with Ms. Kneer, the documents give her record authority to do so. Moreover, as the building permit application suggests (filed in Ms. Kneers name, but with the instruction that Ms. Mead was to be the sole contact, see n. 2, supra), Ms. Mead may very well have effective practical control of the land. Accordingly, on the present record, there is a genuine issue of material fact regarding control that precludes the grant of summary judgment on that issue to either side. See Phelps v. MacIntyre, 397 Mass. 459 , 461 (1986).

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, I ALLOW the plaintiffs motion for summary judgment on the question of whether Lots 46 and 47 merged with adjacent Lots 48 and 49 at the time the 1953 zoning bylaws were enacted, ruling that they were grandfathered from merger at that time by the language of the bylaw, and DENY the parties cross-motions for summary judgment in all other respects, ruling that the question of whether Lots 46 and 47 subsequently merged with Lots 44 and 45 due to effective common control presents genuine issues of material fact requiring trial to resolve.

SO ORDERED.

parcel 19-1. Lots 44 and 45, titled in Ms. Meads name individually, are shown as parcel 19-7.

MILDRED KNEER, as trustee of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.

MILDRED KNEER, as trustee of the Kneer Family Revocable Trust, v. ROBERT LUCIANO, MICHAEL KULESZA, CHRISTOPHER WIDER and DONALD HANSSEN as members of the Norfolk Zoning Board of Appeals, and THOMAS MURRAY.