Plaintiff Robert Talmo (Talmo) filed this appeal, pursuant to G. L. c. 40A, §17, of a decision of the Framingham Zoning Board of Appeals (the Board) upholding the Framingham building commissioners denial of Talmos request for zoning enforcement at defendants Carleton Buckley and Heidi Pihl-Buckleys (the Buckleys) property. Talmo resides at 28 Nixon Road, Framingham (the Talmo Property) and the Buckleys reside at 30 Nixon Road, Framingham (the Buckley Property). The Buckley Property is improved by a single-family home, which is occupied as the residence of Ms. Pihl-Buckleys parents, and a former barn occupied as the residence of the Buckleys and their children. Talmo alleges that the Board and the building commissioner incorrectly determined that the former barn is an allowed accessory use to the other house on the Buckley Property, and not an impermissible second single-family dwelling on one lot for purposes of the Town of Framinghams Zoning Bylaw (the Bylaw).

In 2009, Talmo first sought zoning enforcement from the building commissioner, requesting that the Buckleys cease using the former barn as a residence, since only one single-family dwelling on a lot is permitted in the Buckleys zoning district under the Bylaw. After the building commissioner denied the enforcement request, Talmo appealed to the Board. The Board reversed the building commissioners decision, finding that the Buckleys use of the former barn as a residence did violate the Bylaw.

On June 7, 2010, the Buckleys filed a building permit application seeking to convert the existing barn to additional living space for the main house. Not to be used as a separate dwelling. Not to include permanent provisions for cooking. A building permit was issued to the Buckleys on June 17, 2010 (the 2010 Permit), after which the Buckleys removed their stove and oven from the kitchen in the former barn. On October 18, 2010, Talmo again sought zoning enforcement from the building commissioner. The building commissioner denied Talmos request for enforcement on October 26, 2010 (the 2010 Denial), and Talmo appealed the second denial to the Board. The Board denied Talmos appeal, after which he filed a complaint with this court on March 9, 2011.

Talmo asserts that the Board incorrectly denied his appeal of the 2010 Permit because the former barn constitutes an illegal second dwelling on a lot in a single-family district. The Buckleys argue that the building commissioners interpretation of the Bylaw was correct and the former barn should not be considered a dwelling. In the alternative, the Buckleys argue that Talmos request for zoning enforcement was untimely, and as a result, the appeal should be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

A trial was held on December 8, 2015, and I conducted a view on the following day, December 9, 2015. For the reasons stated below, I conclude that the plaintiff lacks standing, this court accordingly lacks subject matter jurisdiction to hear this appeal, and thus, the plaintiffs First Amended Complaint must be dismissed.

FACTS

Based on the facts stipulated by the parties, the documentary and testimonial evidence admitted at trial, my view of the subject properties, and my assessment as the trier of fact of the credibility, weight and inferences reasonably to be drawn from the evidence admitted at trial, I make factual findings as follows:

1. On August 19, 1999, the property located at 28 Nixon Road, Framingham, was conveyed to Talmo pursuant to a deed recorded in the Middlesex County South District Registry of Deeds (Registry) in Book 30602, Page 233.

Joint Stipulation of Undisputed Facts (Tr. Stip.), ¶ 1, and Agreed-Upon Exhibits (Ex.)1.

2. The Talmo Property consists of two parcels, together comprising approximately seventeen acres, and improved with a single-family dwelling. Ex. 1; view.

3. On September 15, 2009, Edgar and Phyllis Pihl (the Pihls), parents of defendant Heidi Pihl-Buckley, conveyed the property at 30 Nixon Road, Framingham, to the Buckleys pursuant to a deed recorded in the Registry in Book 53557, Page 520. Tr. Stip. ¶¶ 3-4; Exs. 2-3.

4. The Buckley Property is a 1.31 acre parcel of land improved by a single-family dwelling occupied by the Pihls as their principal residence, and by a building that was formerly a barn, presently occupied by the Buckleys as their principal residence.

See Defendants Answer to First Amended Complaint (Ans.) Ex. 1; view.

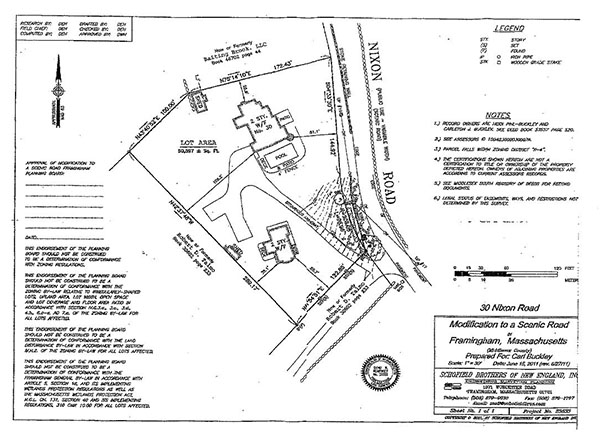

5. The Talmo Property and the Buckley Property abut each other. The house on the Talmo Property, in which the plaintiff resides, is located approximately 250 feet from the southwesterly, rear boundary line of the Buckley Property closest to the former barn. The distance from the house on the Talmo Property to the former barn on the Buckley Property is in excess of 250 feet, and probably in excess of 275 feet. [Note 1] Ex. 3 (attached here as Exhibit A); view.

6. As the plaintiff acknowledged at trial, his house is a substantial distance from the former barn on the Buckley Property. [Note 2] View.

7. Both properties are situated in Framinghams R-4 Single Residence Zoning District (R-4 district). Uses allowed in the R-4 district include a single-family dwelling. Two single- family dwellings on one lot are not permitted in the R-4 district. Tr. Stip. ¶¶ 5-6, 17; Exs. 3 (attached here as Exhibit A), 10.

8. Trees, boulders and other landscaping features are located along the boundary line between the properties, partially blocking the view from the Talmo Property of the former barn on the Buckley Property. Tr. 1:35-37; Exs. 7E-H; view.

9. The original house on the Buckley Property, where the Pihls currently reside, was constructed in or around 1956 (the Pihl House). The Pihl House is 1.75 stories and has seven rooms, including three bedrooms, one full bath, and one half bath. Tr. Stip. ¶¶ 7-8.

10. Approximately in 1971, a two-story wood barn was constructed on the Buckley Property. Originally, the Pihls used the barn as a horse stable and then later for storage. Tr. Stip. ¶ 9.

11. During the mid to late 1980s, the barn was converted into a residence, without the benefit of any permits authorizing the use of the building for residential purposes. The Buckley family, Heidi Pihl-Buckley, her husband Carleton Buckley, and their two children, have resided in the former barn as their principal residence since the mid to late 1980s. The Buckleys two children, now young adults, grew up in the former barn. Tr. 1:47-49; Tr. Stip. ¶¶ 12; Ex. 7.

12. On or about November 18, 2004, Edgar Pihl applied for a building permit to construct an addition to the barn consisting of a 12 x 24 great room with foundation. The application and plans were filed with the Town of Framingham Department of Building Inspection. On November 29, 2004, the building commissioner issued a building permit (the 2004 Permit) to build the 12 x 24 addition. The addition complied with all setback, height, and dimensional requirements. Tr. Stip. ¶¶ 10-12; Exs. 5-6.

13. The former barn, as enlarged by the 2004 great room addition, currently has three bedrooms and two baths on two floors, in addition to other rooms, including a living room and a kitchen. The kitchen has all the appearances of a kitchen in a single-family dwelling, with a refrigerator, counter, cabinets and sink, with the exception that there is an empty space between the end of the counter and a wall where the stove and oven were evidently removed, and above that space where there is the appearance that a microwave

oven had formerly been mounted on the wall. [Note 3] Despite there being no wall-mounted microwave oven, there is a microwave oven in the kitchen, and the Buckleys also use an outdoor gas grill, on a patio just outside the back door, for cooking.

14. On December 18, 2009, Talmo requested zoning enforcement from the building commissioner, asking that he enforce the Bylaw and issue an order to the Buckleys to cease utilizing the barn as a residence. On January 7, 2010, the building commissioner sent a letter declining to take enforcement action in the matter. Tr. Stip. ¶ 13; Exs. 8-9.

15. Talmo appealed to the Board on February 18, 2010, and a public hearing was held on March 9, 2010, the subject of which was whether the former barn was being occupied as a dwelling in violation of the Bylaw. Exs. 9-10.

16. In May, 2010, the Board overturned the building commissioners decision not to take zoning enforcement action. The Board concurred with Talmos position, that under the Bylaw, two single-family dwellings are not permitted within an R-4 district and that the former barn, now occupied as a dwelling, violated the Bylaw. Tr. Stip. ¶ 14; Ex. 9.

17. On June 7, 2010, the Buckleys filed a building permit application seeking to convert the existing barn to additional living space for the main house. Not to be used as a separate dwelling. Not to include permanent provisions for cooking. Tr. Stip. ¶ 15; Ex. 18.

18. On June 17, 2010, the application was approved and a building permit (the 2010 Permit) was issued by the building commissioner on the condition that the alteration was not to include permanent provisions for cooking. Tr. Stip. ¶ 16; Ex. 19.

19. In accordance with the 2010 Permit, the Buckleys removed their stove and oven from within the premises of the former barn and had the stove connection capped off. Tr. 1:50; Ex. 20.

20. Through an exchange of emails between his counsel and the building commissioner, Talmo received notice of the issuance of the 2010 Permit on July 29, 2010. There was no evidence at trial to suggest that Talmo had actual or constructive notice of the issuance of the 2010 Permit prior to July 29, 2010, and I so find that Talmo had neither actual nor constructive notice of the issuance of the 2010 Permit at any time prior to July 29, 2010. Tr. 1:30-31;; Exs. 14, 22-23.

21. The following day, on July 30, 2010, Talmos attorney wrote a letter to the Framingham Board of Health Director seeking enforcement of the State Environmental Code against the Buckley Property as it pertains to its septic system. Ex. 15.

22. On October 18, 2010, Talmo wrote a letter to the building commissioner again seeking zoning enforcement. He did not appeal the issuance of the 2010 Permit. Tr. Stip. ¶ 18; Ex. 11

23. On October 26, 2010, the building commissioner denied Talmos request for enforcement (the 2010 Denial), taking the position that although the Bylaw precludes more than one dwelling on a lot in an R-4 district, the Bylaw did not define the phrase dwelling unit. The building commissioner looked instead to the state building code definition of dwelling unit: a single unit providing complete independent living facilities for one or more persons, including permanent provisions for living, sleeping, eating, cooking, and sanitation, 780 CMR 5202. The commissioner found that the removal of the stove and oven from the former barn meant that it no longer had permanent provisions for cooking, and thus, could not be classified as a dwelling, but rather as an accessory use. The building commissioner also found that the addition built pursuant to the 2004 Permit complied with the dimensional requirements of the Bylaw and the 2004 Permit was properly issued as-of-right. Accordingly, he stated, there are no grounds for taking zoning enforcement action with regard to the 2004 addition. Tr. Stip. ¶ 19; Exs. 4, 12.

24. On November 12, 2010, Talmo appealed the building commissioners 2010 Denial to the Board. Tr. Stip. ¶ 20; Exs. 4, 13.

25. On February 18, 2011, the Board denied Talmos appeal, affirming the decision of the building commissioner not to pursue zoning enforcement. Tr. Stip. ¶ 21; Ex. 4.

26. On March 9, 2011, Talmo filed his appeal of the Boards decision affirming the building commissioners 2010 Denial with this Court.

DISCUSSION

The parties present two arguments with respect to the courts review of the merits of the Boards decision. First, whether Talmos request for zoning enforcement was untimely, thus depriving the court of jurisdiction. Second, whether the building commissioner correctly interpreted the Bylaw in concluding that the removal of the stove constituted the elimination of a permanent provision for cooking, thereby rendering the former barn merely an accessory living space to the house occupied by Ms. Pihl-Buckleys parents, and no longer an illegal second dwelling unit on a single lot in a single-family zoning district. But before I can address these arguments, I must address the issue of standing, and whether Talmo is a person aggrieved within the meaning of G.L. c. 40A, §17, something the Buckleys, representing themselves without an attorney, failed to explicitly address.

STANDING

Standing presents a question of the subject matter jurisdiction of the court that must be resolved before proceeding to the merits. Planning Bd. of Marshfield v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Pembroke, 427 Mass. 699 , 703 (1998); BAC Home Loans Serv. LP v. Kay, 21 LCR 50 , 50 (2010) (Standing is a matter of subject matter jurisdiction.); U.S. Bank, NA v. Sarourim, 20 LCR 151 , 151 (2010). If the plaintiff does not have standing, the court has no jurisdiction to hear the dispute. Monks v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals, 37 Mass. App. Ct. 685 , 687 (1994) (subject matter jurisdiction is a prerequisite to judicial review). Although the Buckleys did not raise this issue explicitly, standing, as it pertains to subject matter jurisdiction, cannot be waived by the parties, and thus, can be considered by the court sua sponte at any time. Durand v. IDC Burlingham, LLC, 440 Mass. 45 , 61 (2003) (Although the parties do not raise the issue of standing, [the] court can raise the issue on its own because it goes to subject matter jurisdiction.); McDonough v. Moriarty, 13 LCR 169 , 170 (considering standing sua sponte after plaintiff failed to allege facts showing he was aggrieved by a zoning board of appeals decision); see also Morse v. Fed. Natl Mortgage Assoc., 23 LCR 159 , 160 (2015); Prudential-Bache Secs. Inc. v. Commr of Revenue, 412 Mass. 243 , 248 (1992); Abate v. Fremont Inv. & Loan, 470 Mass. 821 , 828 (2015). Based on the evidence presented at trial and the view taken of the subject property, I now raise and consider the issue of standing.

G.L. c. 40A, § 17 provides in relevant part that [a]ny person aggrieved by a decision of the board of appeals . . . may appeal to the land court department

Abutters to the subject property are entitled to a rebuttable presumption that they are aggrieved persons within the meaning of § 17. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, 461 Mass. 692 , 700 (2012); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, 421 Mass. 719 , 721 (1996); Choate v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Mashpee, 67 Mass. App. Ct. 376 , 381 (2006). The Talmo Property directly abuts the Buckley Property. Therefore, Talmo is entitled to the presumption that he is aggrieved. If standing is challenged, the jurisdictional question is decided on all the evidence with no benefit to the plaintiffs from the presumption. Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, supra, 421 Mass. at 721, quoting Marotta v. Bd. of Appeals of Revere, 336 Mass. 199 , 204 (1957).

The party challenging the plaintiffs presumption of standing as an abutter can do so by offering evidence warranting a finding contrary to the presumed fact. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, supra, 461 Mass. at 700, quoting Marinelli v. Bd. of Appeals of Stoughton, 440 Mass. 255 , 258 (2003). If a defendant offers enough evidence to warrant a finding contrary to the presumed fact, the presumption of aggrievement is rebutted, and the plaintiff must prove standing by putting forth credible evidence to substantiate the allegations. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, supra, 461 Mass. at 701.

Following rebuttal of the presumption by a defendant, plaintiffs have the burden of proving, by direct facts and not speculative evidence, that they would suffer a particularized injury as a consequence of the issuance of the permit. Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, 459 Mass. 115 , 120 (2011). The facts offered by the plaintiff must be more than merely speculative. Sweenie v. A. L. Prime Energy Consultants, 451 Mass. 539 , 543 (2008). On the other hand, if a defendant fails to offer sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption of standing, then the abutter is deemed to have standing, and the case proceeds on the merits. 81 Spooner Road, LLC v.

Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Brookline, supra, 461 Mass. at 701.

If the plaintiffs presumption of standing is rebutted, the plaintiff bears the burden to present evidence establishing that he will suffer some direct injury to a private right, private property interest, or private legal interest as a result of the decision that is special and different from the injury the decision will cause to the community at large, and that the injured right or interest is one that c. 40A or the Bylaw is intended to protect. Id. at 700; Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, supra, 459 Mass. at 120; Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, 447 Mass. 20 , 27-28 (2006); Marashlian v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Newburyport, supra, 421 Mass. at 721; Butler v. City of Waltham, 63 Mass. App. Ct. 435 , 440 (2005); Barvenik v. Board of Alderman of Newton, 33 Mass. App. Ct. 129 , 132-133 (1992); Ginther v. Commissioner of Ins., 427 Mass. 319 , 322 (1998). Aggrievement is not defined narrowly; however, it does require a showing of more than minimal or slightly appreciable harm. Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, supra, 459 Mass. at 121-123 (finding the height of a new structure to have a de minimis impact on plaintiffs ocean view).

Although the Buckleys did not themselves explicitly offer evidence to rebut Talmos presumption of standing, I find that the plaintiffs presumption of standing was rebutted by credible evidence, including the plaintiffs own testimony on direct examination that his home is substantially farther from the Buckley Property than can be shown on the plan admitted into evidence as Exhibit 3. This was confirmed and amplified by my view, which showed the distance between the houses on the two properties to be considerable, with intervening landscaping. [Note 4]

The Talmo Property consists of two parcels totaling approximately 17 acres, while the Buckley Property of 1.31 acres is much smaller. At trial, Talmo testified to the relationship between his property and the Buckley Property. In reference to a plan of the Buckley Property, attached here as Exhibit A, Talmo stated that his house is located off the bottom left of the plan, substantially farther from the boundary line of the Buckley Property and the former barn than could be shown on the plan. The view taken on December 9, 2015 supports, confirms, and amplifies this testimony. During the view, confirming Talmos testimony as to the substantial distance between the two properties, I observed that the house on the Talmo Property is located a considerable distance from the Buckley Property, at least 250 feet and up a gradual incline from the Buckleys boundary line and the former barn. Talmos residence is at the end of a long driveway beginning at Nixon Road, which runs along the southwest boundary of the Buckley Property. His house is well to the rear of the rear property line of the Buckley Property. Access onto the Talmo Property from Nixon Road is separate and distinct from the access point onto the Buckley Property, with no suggestion that any additional traffic resulting from the use of the former barn as a converted house has any conceivable effect on Talmos access to his property. The neighborhood is more properly characterized as rural than suburban, with few other houses near the Talmo and Buckley properties, and a working farm (Hanson Farm) a short distance down the road. From Nixon Road, the two dwellings on the Buckley Property have the appearance of two separate, single-family dwellings that share a common driveway. Photographs admitted in evidence show trees, boulders, and other landscaping features along the common boundary line between the Talmo and Buckley Properties, directly between the former barn and the house on the Talmo Property. At the view, it was evident that this bordering landscaping partially blocks the view from Talmos property to the former barn. This evidence at trial, as confirmed by the view, was sufficient to rebut the presumption.

Once the presumption was rebutted, the burden rest[ed] with the plaintiff to prove standing [i.e., aggrievement], which require[d] that the plaintiff establishby direct facts

that his injury is special and different from the concerns of the rest of the community. Kenner v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Chatham, supra, 459 Mass. at 188, quoting Standerwick v. Zoning Bd. of Appeals of Andover, supra, 447 Mass. at 33, and Barvenik v. Bd. of Appeals of Newton, supra, 33 Mass. App. Ct. at 132. This the plaintiff failed to do, offering no evidence at all concerning any injury of any kind to his property as a result of the offending use of the Buckley property. Further, it is unlikely that any such credible evidence could have been offered. The distance between the houses is great enough that it is virtually inconceivable that traffic, noise or light from the former barn, now occupied as a residence, could disturb or injure Talmo

in the use of his property, and there was no evidence to suggest otherwise.

Based on the evidence, as confirmed by the view taken of the properties, I find and rule that the plaintiffs presumption of standing was rebutted, and that the plaintiff failed to offer or show by any credible evidence any particularized harm that would affect him in the use of his property from the continued occupancy of the former barn as additional living space, even if that occupancy was properly characterized as a second dwelling unit on the Buckley property. After scouring the complaint, the trial testimony, and other documents Talmo has submitted to the court, I find that Talmo never alleged, offered in evidence, or proved any particularized aggrievement regarding the zoning decision he now challenges. Talmo has not alleged or proved a harm to any private right or property interest resulting from the Buckleys continued use of the former barn as a dwelling, let alone a harm that is protected by the zoning laws. Accordingly, I find that Talmo did not have standing to bring this appeal and therefore the complaint will be dismissed for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

Because this court does not have jurisdiction over this appeal, I do not reach the merits of Talmos claim. However, the result in this action should not be seen as a vindication of the building commissioners decision or the Buckleys argument that the residence they inhabit is properly characterized as accessory living space for the main dwelling on the Pihl Property. The conversion, without a zoning variance or other appropriate zoning relief, of an accessory barn into something that cannot fairly be called anything but a second principal dwelling on a single-family lot is not to be condoned or justified by the fiction that it is occupied only as accessory additional living space for the main dwelling on the property. Nor is it somehow converted into a legal use by the removal of a stove, when, notwithstanding the lack of a stove, it is plainly occupied as a second single-family dwelling on a lot where only one single-family dwelling is allowed by the Bylaw.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, I find and rule that Talmo lacks standing to seek zoning enforcement against the Buckley Property. Judgment shall enter dismissing the action with prejudice. [Note 5]

Judgment accordingly.

A: It would be - - where on the paper? It would be substantially farther - - further away.

A: Towards the bottom of the page.

A: Bottom left.

ROBERT D. TALMO v. PHILIP R. OTTAVIANI, JR., et. al., as They Are Members of the FRAMINGHAM ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS; and CARLETON J. BUCKLEY and HEIDI PIHL-BUCKLEY.

ROBERT D. TALMO v. PHILIP R. OTTAVIANI, JR., et. al., as They Are Members of the FRAMINGHAM ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS; and CARLETON J. BUCKLEY and HEIDI PIHL-BUCKLEY.